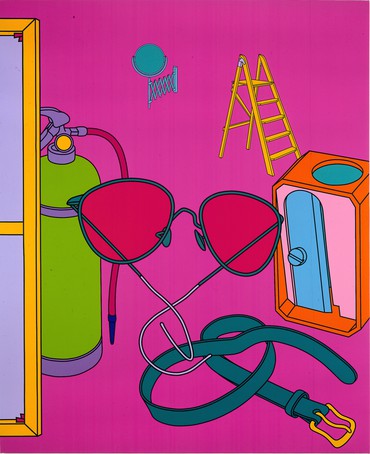

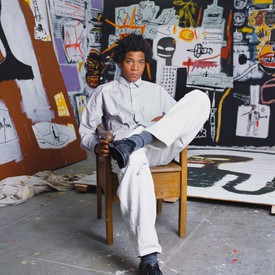

A principal figure of British conceptual art, Michael Craig-Martin probes the relationship between objects and images. The perceptual tension between object, representation, and language has been a central concern in his work over the past four decades. Photo: Caroline True

Samuel Gross has been an independent curator and art critic since 1999. He was head curator of the Istituto Svizzero in Milan, Rome, and Palermo from 2016 to 2020, and is currently working on a renovation project with the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva.

Michael Craig-MartinI’ve always loved the term artist, because it covers so many different things. To say you’re a painter, to say you’re a sculptor, it’s a bit too specific. I’ve always seen myself as an artist, and I’ve had a career where I’ve done many different things. I have certain central ideas, which are mostly instinctive, and I follow where my work is taking me. Over the years, it’s taken me along many different routes that I would have never expected to take.

Samuel GrossThere are several opportunities to see your work at artgenève, including the installation you presented on Bond Street in London last year [in July 2019], which is a series of flags based on some of the motifs that appear in your paintings. There are also some of your paintings on view here. Could you explain the connection between what we see and the objects represented, if there is one?

MCMFrom the very beginning of my work, I’ve been interested in ordinary objects. I have a sense that things that are very important exist within ordinary things, and that everything that’s very important is very close to us, we just can’t always see it. And so in my early work, I started to use real objects, found objects, and then there came a point where I decided to look at images of objects, which I did essentially by making a drawing of a single object at a time, an ordinary object: a table, a shoe, an umbrella. I started to build a vocabulary of these images, without a particular idea of how I’d use them. And the vocabulary grew and grew. With these images, I started making wall drawings, then installations, and I discovered that I had found a language for these things.

When I started drawing, I thought that images of this kind existed in the world. And to my amazement, when I looked for them, they didn’t; I had to make them for myself. But I didn’t want them to look like I had done them. I wanted to draw them with a perfect line that would look like it had been done by a machine. The only objects I draw are mass produced, and I wanted the drawing to look like the objects themselves. Nobody makes a mass-produced object that looks like a piece of junk; they become junk, but they don’t start like that, they always start perfect.

SGDid you begin these kinds of drawings by hand, later moving on to computer design?

MCMI started by making individual drawings of objects, and I wanted to have something with no hierarchy. So I would use a sheet of paper of a certain size, and I would draw every object as big as the paper. If it was a table, it had to fit in the paper; if it was a safety pin, it also had to fit in the paper. I didn’t want hierarchies of scale, hierarchies of value; I wanted something where everything was treated identically.

SGLike a technical map?

MCMYes, and very straightforward. No moralizing about it—I’m not talking about consumerism; I’m just observing these things. I started by drawing them by hand, and then tracing them with tape on acetate. Those drawings became templates for other drawings. Once I drew a book I never drew another book; I traced the book I had.

So I was building a vocabulary, and I used that vocabulary over and over again. That’s what we do with language: there are millions of words, but we have about two thousand, at most, that we use all the time. We don’t use all the other ones, but the ones we use, we use constantly, again and again and again. We put them together in slightly different ways that make different sentences, with slightly different meanings. We’re not thinking all the time “this is so boring because we use the same old words.”

In the early ’90s, I got my first computer—a very simple computer, tiny memory—for word processing, because I could never write from beginning to end. I could only write chunks, and then I would collage the bits. And when I got the computer and did that, I suddenly thought, “That’s how I make my visual work too; I make the individual drawings and then I collage.” Then I started to scan all my drawings, and after that I started to draw them myself. Now I don’t use any paper, I draw everything with a mouse on a computer. I’ve done that for fifteen, twenty years.

To be honest, it’s as though I’d been waiting for them to invent the computer for my work. Everything I’ve done for the past twenty years, thirty years, I could never have done without the computer. When you have a physical template and want to make it 10 percent bigger, you have to make another template; that’s exhausting, you can’t do that. Whereas on the computer, 10 percent is the push of a button. You want it to be red, it’s red, blue, it’s blue, just like that, and you can save it. If you make forty versions and then forget what the first version was like, you can go back. This has made all of my work possible.

If you go back to all the ancient languages—Egyptian hieroglyphs, Chinese script—this is where images become abstracted into words. I think that at the root of all communication is image making.

Michael Craig-Martin

SGAre these images for you a real vocabulary? Can you choose them like words?

MCMTo me, the objects that we make, the ordinary objects of use, the objects of daily life, that is the greatest record of who we are right now. When we look at ancient societies—at Egypt, or Greece, or back to the Aztecs—we look at the things they produced in order to understand the society they were. We express ourselves through the objects that we make. I don’t make shoes and I don’t make laptops; I just make pictures.

There is a miracle about being able to make a picture of something. It allows you to “have” the object, to play with it, without the physical object. We have the presence of the object that is absent. So you can do something with the drawing of a shoe; you don’t need the shoe once you have the drawing. It’s also hard to make a shoe twenty feet big. But a twenty-foot drawing is no problem.

If you go back to the cave paintings, they took the things that were most important to them, and they drew them on the wall. They drew bison much larger on the wall. They understood that just drawing it brought the presence of the bison into the magic zone of the cave. It seems to me that this relation of images to language, verbal language, is underestimated. If you go back to all the ancient languages—Egyptian hieroglyphs, Chinese script—this is where images become abstracted into words. I think that at the root of all communication is image making.

SGThere is a huge part missing in the simple drawing of an object, isn’t there? And that’s its use.

MCMIn my early work, one of the first things that interested me was: What is the difference between a chair and a sculpture? Why is one a work of art and not the other? Of course you can see the chair as a readymade, you can make it art, but how is that? The thing about a chair, and all ordinary things, is that nobody makes anything without use. Every one of the objects that I draw starts with a need, a use. I don’t make shoes; I make pictures. And so, what kind of use can pictures have in our lives and in the world? It’s not that there’s no use; it’s just a different kind of use.

SGWhen I look at your image of a shoe, I’m not seeing any shoe, I’m seeing one you have consciously chosen among infinite options. Are we speaking about taste, then?

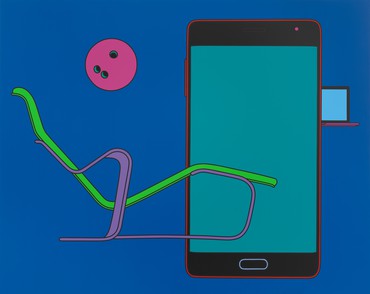

MCMTo a certain extent we are, yes. Certain objects of the past, historical objects—the lighbulb, for example—somebody designed it, but we don’t think about objects like that as having been designed. Today, we are conscious that there is a designer behind almost everything we have. I never draw anything in a general way, I always draw something. So if I’m going to draw a trainer, I have to choose a trainer to draw. If I’m going to draw a phone, I have to choose one: am I going to do a Samsung or an iPhone? There is no general phone for me to draw, because none of them exist like that. The question of branding has entered into the nature of ordinary objects.

So many things have changed about objects. When I started making drawings of things in the ’70s, it was pretty safe to think of objects as form following function, and most of the objects of that time are what they are in order to do what they need to do. When you look at them, you can see their function; they tell you what to do by their scale, by their material. Today, the iPhone is a camera, a computer, a calendar—it’s twenty different objects in the blandest object of all. You have no idea, when you pick up the phone, where to speak and where to listen. Nothing is obvious. This is an incredible change in the nature of objects. Now microwaves look like televisions, televisions look like nothing, everything is looking more and more like one thing. In my view, the world of the richness of objects might be a period in history.

SGHow does your personal taste fit in?

MCMI don’t think of my work as an expression of my taste. My work is different. When you come to my house, it’s not a multicolored environment, it’s black and white and gray. The work is something that exists differently, that has its own life, and I’m the agent of this. I’m not trying to project my taste onto other people or to recommend it. The work may come to create a taste for other people, but that’s not coming from my personal taste.

SGWhen I was thinking about taste, I was also thinking about time. Did you wish, as other artists do, to escape the chronological rationality of time? If you choose an object in today’s world, it might become obsolete very rapidly. Have you noticed the speed at which we exhaust this visual vocabulary, turning back to older objects?

MCMWhen I started doing those things, it never really occurred to me that they would become dated. In the ’70s and ’80s, I thought these were things that would last forever—classic things. I did the most wonderful drawing of a tape cassette in the ’80s. I can’t draw that anymore, because no one under thirty has any idea what a tape cassette is! Now, I’ve drawn an iPhone 6, an 8, and a X—when I’m drawing, I’m trying to keep up. And the thing is, in ten years, people might look at the iPhone and think, “What was that? What did we use this for?” They have a very, very short life. At first, I refused to draw things that would change so quickly. But then I realized that if I do that, I’m leaving out half of modern life. I also wasn’t so sure about drawing something that was so expensive. To be ordinary was to be available to everybody. These phones cost a thousand pounds, they’re very expensive, and yet they’re ubiquitous, you can’t talk about modern life and not mention them.

So, many things that were true of objects in one period cease to be true. I’m trying all the time to keep the things that I’m drawing in tune with the present. If the present lasts for five years, I’m making a record of those five years.

SGDo you have the same feeling about the use of color? A Pop historian would say that this vocabulary comes out of the postwar period, the discovery of the capacity to produce these colors. What is the connection you have with the colors that you use?

MCMObviously, when I make the drawings, they’re very precise, very factual, I never distort an image, I try to draw it as accurately as I can. The color is completely arbitrary. It is instinctive on my part, but I’m trying to do certain things with it. A shoe, for example, has amazing physical presence. When I make a drawing of it, I do get the presence of the shoe, but what I don’t get is the material of the shoe, the color of the shoe, many physical aspects. The color has to compensate for everything that’s missing in the drawing. And in order to do that, I need the color to be intense, because I’m trying to compensate for physicality. So in the language of picture making color is the way in which materiality is expressed.

SGYou’re also not afraid of reducing your drawings to a line. I’m fascinated by your new works, the sculptures composed of a line floating in space. You take the risk of the drawing’s own space disappearing.

MCMOver the years, most of my work has really been about two-dimensional image making. That’s what interests me. When I make a sculpture, I don’t make a sculpture of an object; I make a sculpture of a drawing of the object. My sculptures are themselves flat. The way in which you read the sculpture is two-dimensional. You stand at the front and you see the image perfectly because you use two-dimensional understanding to read the image. They’re different than most sculptures because they’re sculptures of drawings, not objects.

SGI’m very touched by the way you describe your sculptures. Many say that we’re on our way to losing our capacity of projection. Thanks to you, we know that as humans, we are able to project ourselves. Every time I see one of your pieces, I feel a kind of joy to be alive and see what is around me.

MCMThat’s the best compliment. Thank you so much.

Artwork © Michael Craig-Martin; this program was presented as part of artgenève/art talks, éditions 2020, Geneva, January 31, 2020