Gillian Jakab is an editor, online and print, of Gagosian Quarterly and has served as the dance editor of the Brooklyn Rail since 2016.

In April 1960, four days after returning from a trip to Spain, Frank O’Hara dashed off the poem “Having a Coke with You.” The open arms of the second person beckon anyone in; we are at home in the delights of Frank’s quotidian world. But eventually a clue emerges of the poem’s very real recipient, whose thrall over Frank outpaces some impressive competition:

and the fact that you move so beautifully more

or less takes care of Futurism

just as at home I never think of the Nude

Descending a Staircase or

at a rehearsal a single drawing of Leonardo or

Michelangelo that used to wow me

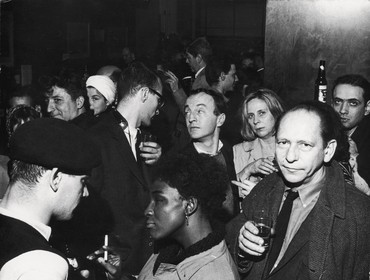

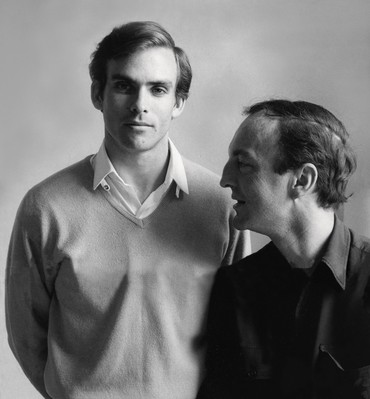

A “poet among painters,” O’Hara could be found most nights in the late 1950s and ’60s at readings, exhibitions, studios, dinners, or the Cedar Tavern with the many contemporary painters he counted among his intimate friends and wider circle: Larry Rivers, Grace Hartigan, Helen Frankenthaler, and Willem de Kooning, to name a few.1 His weekdays he spent among paintings, first at the front desk, then as a curator, at the Museum of Modern Art. The poem’s precipitating visit to Spain was in fact a research trip for an exhibition he was organizing to open at MoMA that summer, New Spanish Painting and Sculpture. The museum’s dedication of a minigallery to O’Hara last fall attests to his role in celebrating Abstract Expressionism (he helped to curate MoMA’s influential Cold War–driven exhibition The New American Painting, of 1958, and wrote the first monograph on Jackson Pollock the following year) and in championing the movement’s second generation, his friends and contemporaries. The gallery assembles poems, ephemera, and paintings of and in the vicinity of O’Hara to describe how he shaped the history not only of the museum’s own collection but of modern art.

Frank O’Hara reading his poem “Having a Coke with You,” New York, 1966, excerpted from USA: Poetry / Frank O’Hara and Ed Sanders, produced and directed by Richard Moore for KQED and WNET, originally aired on September 1, 1966

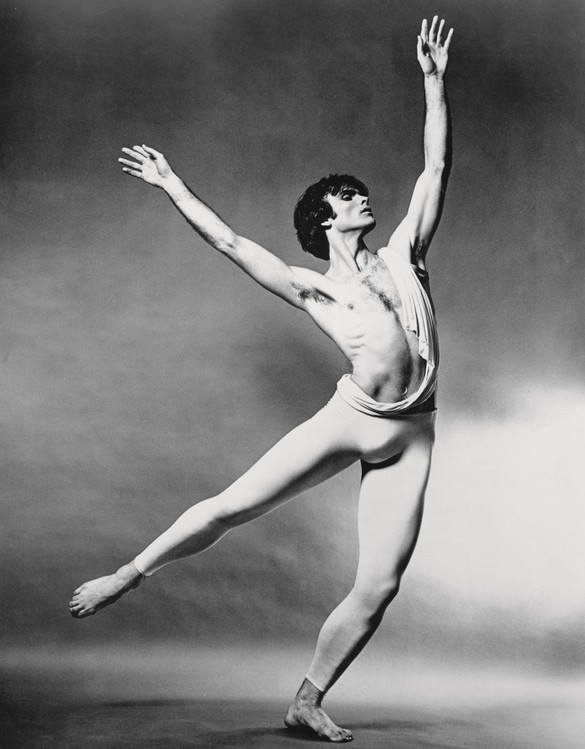

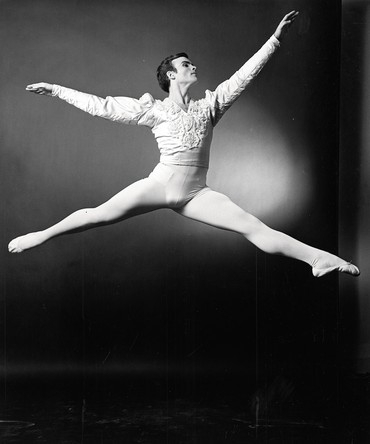

So who could have moved so beautifully as to render Leonardo, Duchamp, and the entire movement of Futurism dispensable? In O’Hara’s eyes, that would have been the not-yet-twenty-one-year-old dancer Vincent Warren. And what to make of these rhetorical devices elevating his lover above greats of the Western canon? In “Having a Coke with You,” as in much of his work, the poet admixes life and art. Here, life seems to come out on top: person over portrait (except maybe Rembrandt’s Polish Rider in the Frick). But we know that O’Hara didn’t sort the world into such stilted categories. As the writer Joe LeSueur, his roommate, and occasional bedfellow, through four apartments, put it, “He didn’t make distinctions, he mixed everything up: life and art, friends and lovers—what was the difference between them?”2 O’Hara aestheticized life and vivified art. And for either to be worthwhile for him, they had to be both immediate and action-filled. Warren, as both lover and dancer, embodied a quality that fed O’Hara’s appetite for a fresh union of life and art, a quality next to which the works of the great painters were found wanting.

In O’Hara’s poem, Warren’s moving, breathing presence at home and on stage is a foil to what’s static and anchored:

It is hard to believe that when I’m with you

there can be anything as still

solemn as unpleasantly definitive as

statuary when right in front of it

in the warm New York 4 o’clock light we

are drifting back and forth

between each other like a tree breathing

through its spectacles

O’Hara devalued both fixed definitions of the past and lofty theories of the future. Instead, he cast his gaze on the ever-shifting present before him and transcribed it in real time with his portable Royal typewriter.3 On the resulting quick, cascading poetry and its bursting imagery, the critic Marjorie Perloff comments that “photographs, monuments, static memories—‘all the things that don’t change’—these have no place in the poet’s world.”4 While O’Hara and the other New York School poets were closely and famously entwined with the Abstract Expressionists, it was the immediacy and dynamism of their work that drew him, not their focus on the inherent characteristics of the medium. Perloff writes, “We can now understand why O’Hara loved the motion picture, action painting, and all forms of dance—art forms that capture the present rather than the past, the present in all its chaotic splendor.”5

A trained pianist, O’Hara kept pace by “playing the typewriter,” in his phrase, anytime, anywhere. His apartment’s revolving door of friends, the city honking by, a typewriter shop at lunch, a trip to an art opening, a party—everything and everyone before him was fodder for his poetry. So naturally, from the summer of 1959, when O’Hara and Warren met, dance—among the most immediate and least mediated of art forms—pops in and out of poems the way a Larry Rivers or Joan Mitchell painting had earlier done. That year is considered O’Hara’s annus mirabilis and marks the beginning of his “Vincent Warren period,” which stretched until 1961 and lines up more or less with what are grouped as his love poems, sixteen of which are collected in Love Poems (Tentative title), published by the art gallery Tibor de Nagy in 1965. These works are held to be among his finest achievements. They’re where he really honed his signature “I do this; I do that” style and are plainly more enjoyable than his headier, symbolist poems. For LeSueur, who had the daily, intimate insight of a roommate, “These marvelous poems testify to what finally came together for Frank, what he at long last experienced, love and the reciprocation of love—physical, sexual, romantic love, fully and deeply realized.”6

For someone to embody this tall order of fulfillment was a feat, and in LeSueur’s estimation, some of O’Hara’s distinguished friends may have raised their eyebrows over Warren, this “unlikely love object.” Besides his youth, there was likely some bias in play against his métier, one continually relegated to the lower ranks of the disciplinary hierarchy: “He was a dancer,” LeSueur writes, “not a poet or a painter or an intellectual.”7 Even this progressive scene retained vestiges of America’s puritanical roots, which divided the mind from body and condemned the latter.

Warren grew up in Jacksonville, Florida, and came to dance not as a child enrolled in class by his parents but through films and books. At the age of eleven, he saw Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1948 film The Red Shoes, in its stunning Technicolor, and began saving for dance lessons and collecting everything dance—newspaper clippings, glossy photographs—in a scrapbook. Cyril Beaumont’s Complete Book of Ballets became his “bible.”8 At seventeen, he left for New York with a scholarship to the school of the American Ballet Theatre (now the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School) and soon won another scholarship to the Metropolitan Opera Ballet School, where he studied with Antony Tudor. With his capacious curiosity and constant reading, he held his own in O’Hara’s avant-garde crowd, proving witty and knowledgeable to those who took the time to get to know him. LeSueur recalls Warren’s wide-ranging artistic interests, from old movies to the history of ballet: he “always seemed to be reading something, either a classic or some obscure book like the Mary Desti autobiography.”9 LeSueur must be remembering Desti’s memoir-cum-biography of the modern dance pioneer Isadora Duncan, an “obscure” reading choice that probably remained with him as it inspired, and is memorialized in, O’Hara’s poem “Mary Desti’s Ass” (1961):

in Bayreuth once

we were very good friends of the Wagners

and I stepped in once

for Isadora so perfectly

she would never allow me to dance again

that’s the way it was in Bayreuth10

By this point Warren, with his infectious enthusiasm, had heaped some hearty doses of dance history onto O’Hara, and a few stanzas later O’Hara references his newfound education. He quickly casts it aside, though, probably because, as always, the living moving before him are more engaging than those frozen in pages:

and Frisco where I saw

Toumanova “the baby ballerina” except

she looked like a cow

I didn’t know the history of ballet yet

not that that taught me much11

Yet O’Hara was clearly soaking it up. One poem dedicated to Warren is titled “At Kamin’s Dance Bookshop,” citing a niche dance shop and publishing house on Sixth Avenue. What’s more, the lovers would go to the ballet together two to three nights a week.12

To be fair, the stream of dance education ran both ways. O’Hara had been friends with dance-world luminaries and a perceptive fan of ballet long before he met Warren. In the couple’s mutual thrillings over dance, the poet would tell of his love for an earlier generation of George Balanchine dancers, many of whom make cameos in his poetry: Maria Tallchief (“John Button Birthday,” 1957), Diana Adams and Allegra Kent (“Poem read at Joan Mitchell’s,” 1957), and Tanaquil LeClercq (a starring role in “Ode to Tanaquil LeClercq,” 1960). And his dear friendship with the poet and dance critic Edwin Denby provided for many an impassioned lobby discussion over the merits of this or that dancer and the latest choreography. LeSueur remembers these ballet debriefs as staples of their lives together: “The three of us—Frank, Edwin, and I—would sometimes adjourn to Edwin’s loft on West 29th Street after the ballet at City Center. We’d drink bourbon, nibble on whatever tidbits Edwin could rustle up, reflect on the ballets we’d seen that night, and then go on to related aesthetic matters.”13

In the introduction to Denby’s essay collection Dancers, Buildings and People in the Streets (1965), O’Hara writes, “Denby is as attentive to people walking in the streets or leaning against a corner, in any country he happens to be in, as he is to the more formal and exacting occasions of art and theatre.”14 O’Hara, like Denby, observed and delighted in movement in all its forms and settings: from the streets (“and the park’s full of dancers with their tights and shoes/in little bags”), to film musicals (“Ginger Rogers with her pageboy bob like a sausage/on her shuffling shoulders, peach-melba-voiced Fred Astaire of the feet”), to the campy social dance of bars (“Button’s buddy lips frame ‘L G T TH O P?’/across the bar. ‘Yes!’ I cry, for dancing’s/my soul delight. (Feet! Feet!) ‘Come on!’”).15

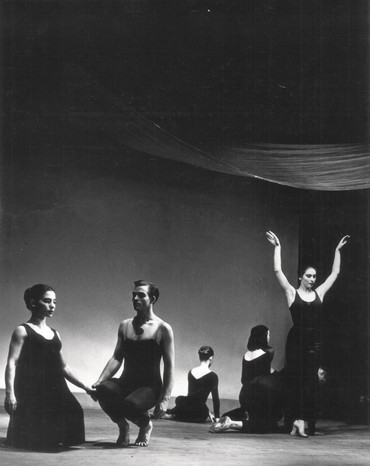

O’Hara shifted seamlessly from the body framed by the proscenium of the Metropolitan Opera to the body rolling on the floor of Judson Memorial Church. In those days, few made the leap from uptown to the downtown dance scene. There were two camps: one of ballet, over which Balanchine presided, and one of modern dance, whose gates were still kept by the old guard of the modern dance of the 1930s (Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, and their stylistic lineages). When Merce Cunningham moved beyond the two camps of the dance world in the early 1950s, he found a home among avant-garde visual artists and musicians, paving a path for the collective known as Judson Dance Theater, which would later become synonymous with “postmodern” dance. At this mid-century moment, Warren was a unique dancer who cast off his ballet shoes and traipsed downtown, shunning distinctions in the fashion of his lover. “I was one of the rare ones who did both because I needed to do both,” he professes in Marie Brodeur’s touching 2016 documentary A Man of Dance, released the year before Warren passed away, in October 2017.

One of Warren’s contemporary-dance performances was in James Waring’s 1958 Dances Before the Wall. The set’s multilayered landscape of boxes grew from the design of Julian Beck, cofounder of the Living Theater, a kind of precursor to Judson where O’Hara had his own plays produced. These politically radical downtown spaces, Warren would recall, are “now sort of put on a pedestal as the hotbed and the birth place of ‘the new dance,’ but at the time it was a funhouse—they were doing crazy things, off the wall things, it was great to be there.”16 This new wave of dance elevated the pedestrian, the everyday, in contrast to ballet’s otherworldly artifice. O’Hara found inspiration in both—the natural and the stylized—fueled by the presentness of Balanchine’s fast, streamlined technique and of Waring’s whimsical, uninhibited compositions. In response to Dances Before the Wall, he wrote an eponymous poem that begins, “a monotonous revery of space is growing/like an early Greek statue I forget how B.C./suddenly everybody gets excited and starts/running around the Henry St. Playhouse.” Here is another statue, again signaling an apprehension of stasis, a fear of boredom, before the action picks up and the poem becomes a parodic web of players in the world of contemporary dance, some now forgotten, others lionized: Midi Garth, Fred Herko (Warren’s roommate), Sybil Shearer, Paul Taylor, Robert Rauschenberg, Doris Hering. And finally the poem, and evening, end: “we go to Edwin Denby’s and quietly talk all night.”17

The poems of the Warren period, beginning with the gleeful “Joe’s Jacket” and concluding on the pained “St. Paul and All That” (written when Warren was moving to Montreal to join Les Grands Ballets Canadiens), represent the height of O’Hara’s powers. They’re full of references to Warren but rarely mention him by name (although his first and last names read acrostically in the first letter of each line of “You Are Gorgeous and I Am Coming,” and his middle name appears in the title of “St. Paul and All That”). The secrecy is usually attributed to Warren’s fear of being outed as gay, especially to his mother, and of the threat that would have carried, in those days, to his career. The result is a low profile among poetry’s great muses. In a considerable number of the poems, however, Terpsichore, the Greek muse of dancing, stands in for Warren and takes center stage among the goddesses.

As for Warren’s legacy, he’s not much more than a footnote in the choreographer-centric American dance canon, but he is a celebrated figure in Canada, where he grew as an artist. Leaving O’Hara’s raucous and consuming New York scene in search of his own identity, he rose to become principal dancer at the Ballets Canadiens and continued to stretch his range, starring in Norman McLaren’s experimental dance film Pas de deux (1968) and also in the Ballets Canadiens ballet set to the Who’s rock opera Tommy (1975). In Warren’s retirement he turned to teaching and his love of dance history, amassing an impressive library, now named the Bibliothèque de la danse Vincent-Warren and housed at L’École supérieure de ballet du Québec.

If it was Warren’s lively beauty and joie de vivre that pushed O’Hara to his greatest work, it was O’Hara’s untimely accidental death, in 1966, at the age of forty, that propelled the love of his life to reach his potential as an artist and dance historian: “To say [O’Hara’s] death was like my birth as an artist, it sounds terrible but it’s probably true. I think that’s what pushed me through, to be not just an okay dancer but to be someone who had something more to show. . . . I think every artist has to have lived before they can make art.”18

All of the poems by Frank O’Hara quoted here appear in The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara, ed. Donald Allen, with an introduction by John Ashbery (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971). In writing this essay, I also relied on Brad Gooch’s City Poet: The Life and Times of Frank O’Hara (New York: HarperPerennial, 1993) and Joan Acocella’s “Perfectly Frank,” The New Yorker, 1993, repr. in Twenty-Eight Artists and Two Saints (New York: Vintage Books, 2007), pp. 471–94.

1The phrase “poet among painters” is the title of Marjorie Perloff’s study Frank O’Hara: Poet among Painters (New York: George Braziller, 1977).

2Joe LeSueur, “Four Apartments,” in LeSueur, Digressions on Some Poems by Frank O’Hara (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), p. xx.

3O’Hara’s feelings about past, present, and future come through in “Joe’s Jacket”: “returning by car the forceful histories of myself and Vincent loom / like the city hour after hour closer and closer to the future I am here / and the night is heavy though not warm, Joe is still up and we talk / only of the immediate present and its indiscriminately hitched–to past / the feeling of life and incident pouring over the sleeping city.” The Collected Poems, p. 329.

4Perloff, “The Aesthetic of Attention,” in Poet among Painters, p. 21.

5Ibid.

6LeSueur, Digressions on Some Poems by Frank O’Hara, p. 224.

7Ibid.

8See Marie Brodeur’s documentary on Vincent Warren, Un homme de danse/A Man of Dance (Montreal: La Compagnie de la Marie/SPIRA, 2016), 83 min.

9LeSueur, Digressions on Some Poems by Frank O’Hara, p. 224.

10The Collected Poems, p. 401.

11Ibid., p. 402.

12See Warren, untitled essay, in Bill Berkson and Joe LeSueur, eds., Homage to Frank O’Hara, 1978 (reprint ed. Bolinas, CA.: Big Sky, 1988), pp. 74–76.

13LeSueur, Digressions on Some Poems by Frank O’Hara, p. 93.

14O’Hara, “Introduction,” in Edwin Denby, Dancers, Buildings and People in the Streets (New York: Horizon Press, 1965), p. 9.

15Respectively from “Steps” (1960), “To the Film Industry in Crisis” (1955), and “At the Old Place” (1955). All from The Collected Poems, respectively pp. 370, 232, and 223.

16Warren, in Brodeur, Un homme de danse.

17The Collected Poems, pp. 334–35.

18Warren, in Brodeur, Un homme de danse.

Video: courtesy http://www.frankohara.org