Andisheh Avini is an artist and a senior director at Gagosian, New York, where he has worked for more than twenty-five years. He works with a number of the gallery’s artists and estates, including Adam McEwen, Piero Golia, the work of Donald Judd and Judd Foundation, and the estates of Steven Parrino and Duane Hanson. He also plays an integral role in curating and producing the gallery’s numerous exhibitions and presenting art fairs.

Patrick Seguin is the founder of the Galerie Patrick Seguin, Paris, which specializes in twentieth-century furniture designed by French architects. He is a member of the Compagnie Nationale des Experts and of the Syndicat National des Antiquaires.

Andisheh AviniNo one has led the charge in twentieth-century design in the way you have. Your stable of architects and designers is specific and you’ve never really swayed from them. That’s an important decision; you’re in a tight market and you’re the leader of it. How do you approach that philosophically?

Patrick SeguinI opened the gallery in 1989 and for the thirty-two years since, I’ve always represented only five names in mid-twentieth-century French architecture and design: Jean Prouvé, Charlotte Perriand, Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, and Jean Royère. As you know, my initial and enduring passion is Prouvé.

Prouvé’s father was a painter, Victor Prouvé, and his godfather was the early-twentieth-century glassmaker Émile Gallé, a major figure in the École de Nancy, the aim of which was to bring all the métiers d’art together as one total art. His family let his genius blossom. Because he used industrial techniques and his work is totally devoid of ornament, we tend to forget that Prouvé was raised in a very artistic environment and always remained close to artists. His father, for instance, once told him that a flower with a hollow stem offers much more resistance than a solid stem, which folds. All Prouvé’s constructional logic ensues from there: solid will never compete with hollow. By bending a steel sheet to form a hollow shape, Prouvé set his fundamentals: robustness, lightness, and material rationality. The legs of his Standard chair, and the compas [axial portal frame] of his demountable architectures, are hollow shapes; as Prouvé said, there’s no difference between building a piece of furniture and building a piece of architecture.

Also, Prouvé was thinking about ecology and the environment before most people in the field. He didn’t want waste, and he said, I’d love an architecture that leaves no trace on the landscape. He was a visionary, a generous humanist, and ahead of his time.

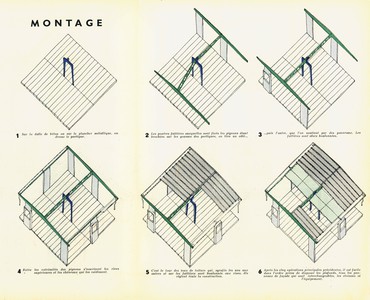

AAHis architecture comes from a place of humanity, and efficiency as well, the innovations of tubular metal in architecture. It’s not only about being efficient and avoiding waste, but also about weight. One of my favorite things to talk about when discussing his houses is how quickly they can be built, how a team of men and women can put together a Prouvé 6 × 6 meter (360-square-foot) house in one day, and that, I’m sure, has a lot to do with weight. I think of Prouvé as the godfather of efficiency leading to sophistication and ultimately beauty. The sum of the parts creates the elegance we cherish in the homes and objects he created in the middle of the last century.

PSProuvé wanted to industrialize housing. He said, The house of my dreams is made in a factory. Not only should the windows be industrially prefabricated, the complete house should be industrially prefabricated and shipped to the site. And he did exactly that. Prouvé operated this factory, with 250 people, in Nancy, where he was born. Then World War II came and Prouvé joined the French Resistance. Nancy and the entire area bordering Germany suffered intense bombing. After the war, the priority of the reconstruction ministry was to get rid of the rubble and mines before even thinking of rebuilding. So Prouvé said, With my factory I can build these small houses. I’ll send three trucks with a team of three people, and three families will get a house in one day. He’d already explored rapidly and easily movable structures before the war, with a 4 × 4 meter military barracks, but after 1939, when he patented his construction system with inversed U- or V-shaped axial portal frames, he really went into developing his concept.

I was speaking with Jean Nouvel about this history, and about the precariousness of these significant architectural creations. We realized that they were all going to disappear unless we adapted them and gave them a second chance to live. And that’s been a deeply important project. I have twenty-four Prouvé houses in my gallery inventory and two of them have been adapted by Jean Nouvel. And a 6 × 6 meter house that I asked Richard Rogers to adapt consistently for modern usage is on loan to my friend Paddy McKillen at Château La Coste in Provence, where it’s currently operated as an additional room of the hotel.

AAIf a new client, or even an existing one, wants to educate themselves about an architect or designer, what do you recommend they do? Museum exhibitions, books—what do you think is the best way to learn? I know you’ve published a great deal on these designers, especially Prouvé.

PSTwenty years ago I published eight hundred pages on Prouvé in two volumes, one on furniture and one on architecture. Over one hundred pages are dedicated to contemporary art collectors’ interiors. One can see the synergy and dialogue that exist between art, architecture, and design. I updated and republished it around five years ago.

AAYou’re very generous with those books. You give them out to people you want to educate—whether it’s a collector or just someone who’s interested, they have information at their fingertips when it comes to Patrick’s books.

PSYes, I like seeing them out in the world. I published a three-part box set with five volumes in each. So it’s fifteen volumes on Prouvé’s architectures, and I published another five, so in total I’d say twenty books on Prouvé. I also published a book retracing the history of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s project in Chandigarh, as well as an extensive monograph on Jean Royère. I produced that together with Jacques Lacoste, with whom I share Royère’s massive archive.

AAYou’re definitely an educator. There’s always a new collector seeking information and something fresh on the eyes, so it never ends, you’re constantly educating. I assume most of your time is taken up by restitution and conservation and bringing these things back to life, whether it’s a house or furniture—as you say, these things could have been lost to history, but you seek them out and find them and bring them back to their glory.

PSYes, but this has evolved. I began over thirty years ago. Now the government realizes that it is patrimony that must be saved. Those Prouvé houses—how many survived? Who knows? Very few. Most of these houses are unique or very limited in number. I remember thirty years ago, people used to say, Oh, but you want to live in this barrack? People didn’t realize they’re not barracks, they’re the cabanas of our dreams when we were kids! I have built five of those houses on our land in the South of France, near St. Tropez. They’re hidden in woods throughout 110 acres of cork oak trees and oak trees. I visit them every day. I arranged one as a hunting and fishing lodge, another as a library, a third as a quiet study . . . They’re historic and inspiring, and highly charged emotionally.

AAThat brings us to an interesting place where our worlds converge. When a collector says, Hey, I’m going to Paris, I say, I need you to go meet Patrick, I need you to see his home. Because the way you live, the way you bring art, furniture, and design together and create this infectious kind of setting—people are mesmerized, they just want to be involved. You invite everyone into your world. And art plays a big role in that, because you have a great collection and it works with such a nice synergy with everything that supports it and functions around it. Tell us a little bit about your passion for art. And let’s not forget some of the collaborations we’ve done bringing artists together with Prouvé—Alexander Calder and Prouvé, John Chamberlain and Prouvé—those were amazing shows.

PSThank you, Andy. I’ve collected contemporary art from the beginning. I’m very close with artists who incidentally find themselves very fond of Prouvé. I had many group shows early on, and not long ago I published a catalogue of one of those shows, Pièces-Meublés, organized with Bob Nickas in 1995. The title has a double meaning: pièce in French means “piece,” in the way you call a work of art a “piece,” and it also means “room.” Meublé means both “furnished apartment” and simply “furniture.” There were twenty-five artists in the show (John Armleder, Louise Lawler, Olivier Mosset, Albert Oehlen, Rudolf Stingel, Franz West . . . ) and each was invited to make a work incorporating a piece of furniture chosen out of my inventory. Most of them picked a Prouvé.

AAYou also have your Carte Blanche program, where you stage exhibitions in collaboration with gallerists.

PSYes, for Carte Blanche I’ve invited twelve galleries so far—Paula Cooper, Sadie Coles, Gagosian, Presenhuber, Kordansky, Massimo De Carlo, et cetera—to do a show in my gallery space during FIAC in Paris. I give them total freedom.

AAWhile Prouvé is all about efficiency and simplicity and a kind of literalism of architecture and materials, you also deal with the work of Jean Royère, who I think is at the other end of the spectrum—his works are about color and whimsy, they feel like things plucked out of your dreams. Tell us about that back-and-forth between your passions for Prouvé and for Royère.

PSRoyère’s life is pretty amazing. Among his predecessors he admired the designers Jean-Michel Frank and Pierre Chareau. He brought fantasy, color, and humor into his furniture, in the Yo-Yo piece, for example. But what I like in Royère is that his work is very serious. There’s a street near my gallery in Paris, the rue du Faubourg Saint-Antoine, in la Bastille. In the early twentieth century, every furniture-maker was there or in the small streets around. So Royère worked for one of these manufacturers, Pierre Gouffé, as a designer making amazing drawings, blueprints, and watercolors. But that wasn’t enough for him; he said, I want to go into fabrication, and he went to the factory to see how things were made. After that, he wanted to see the commercial side, how to make a company. Then he felt ready to build a company of his own. I think Royère is singular with color, shape, line—the Polar Bear sofa, the Eiffel Tower line of furniture. The straw-marquetry furniture pieces take hundreds of hours to make: first you build the frame, then you cut the straw in the middle, flatten it, and glue it delicately to the furniture, making a pattern with it. It’s sophisticated and beautiful but never bourgeois.

AACan you tell us a bit about your involvement in art fairs? What you do is always spectacular, it’s always the biggest effort made at a fair.

PSI always build something. Otherwise I’d just stay home. One year at Design Miami/Basel, we brought a 6 × 6 Prouvé house, one of his houses for refugees. When visitors walked in on the first day, at 11 in the morning there were only crates in the booth. My team opened the crates and took out all the components of the house. In the ninth or tenth hour of the fair, we were setting up the house, building the floor, fixing the compas, and sealing the structure. The house was completed by the end of the day. And that was the entire presentation, no furniture. It was like a performance: we built a house in a booth that looked empty at first sight. On the first day people just saw guys opening crates, but then they understood there was a process going on, like a staged happening, and there were more people every day gathering to watch it. It was quite rewarding.

Photos: courtesy Galerie Patrick Seguin, Paris