As the Keith L. and Katherine Sachs Senior Curator of Contemporary Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Carlos Basualdo has organized the exhibitions Bruce Nauman: Topological Gardens (2009), Michelangelo Pistoletto: From One to Many (2010), and, with Erica F. Battle, Dancing around the Bride: Cage, Cunningham, Johns, Rauschenberg, and Duchamp (2012).

Alison McDonald is the Chief Creative Officer at Gagosian and has overseen marketing and publications at the gallery since 2002. During her tenure she has worked closely with Larry Gagosian to shape every aspect of the gallery’s extensive publishing program and has personally overseen more than five hundred books dedicated to the gallery’s artists. In 2020, McDonald was included in the Observer’s Arts Power 50.

Scott Rothkopf is the Senior Deputy Director and Nancy and Steve Crown Family Chief Curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. He joined the Whitney’s staff in 2009 and has served there as curator or cocurator of Glenn Ligon: america (2011), Wade Guyton OS (2012), Sinister Pop (2012), Singular Visions (2010), Jeff Koons: A Retrospective (2014), America Is Hard to See (2015), Open Plan: Andrea Fraser (2016), Human Interest: Portraits from the Whitney’s Collection (2016), Virginia Overton: Sculpture Gardens (2016), and Laura Owens (2017).

Alison McDonaldThis is an ambitious exhibition presenting over five hundred works of art at two museums in two different cities simultaneously. When did the project begin and how did your conversations and plans evolve along the way?

Carlos BasualdoI understand that it looks ambitious, but ambition was not our point of departure. We’ve long shared an interest in and admiration of Jasper Johns and his work. And the point of departure was, What shall we do to properly address the work in all its complexity? To do that we needed to represent his work across disciplines, including prints, as well as working proofs, paintings, and sculptures. We wanted the show to appeal to a younger generation and we felt that the structure of the exhibition should echo the logic of the work itself. So while it’s ambitious when you look at the list of works, our motivation was to truly represent Johns’s work as faithfully as we could.

Scott RothkopfAs Carlos mentioned, we’ve both had independent and long relationships with Johns, and so have both of our museums, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, going back many decades. We decided we wanted to embark on this show in early 2016, when there was a lot of renewed interest in Johns’s work: he was making and showing new work in Chelsea, the catalogue raisonné of paintings had been completed, and it was the tail end of the catalogue raisonné of drawings. There was a wonderful show the following year that opened at the Royal Academy, London, and traveled to the Broad, Los Angeles. We were excited to learn from the work that was taking place and to create our own exhibition by joining forces.

AMcDThe idea to host a single exhibition across two institutions seems to have been informed by Johns’s own history with mirroring and doubling. Can you speak to that history, and to how the artist’s own work inspired the shape the exhibition took?

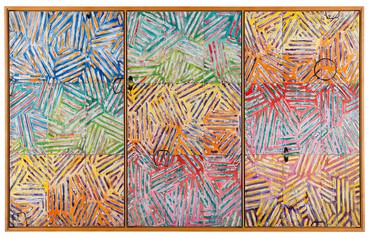

CBWhen we started thinking in that direction, we were both surprised to realize how deep repetition, mirroring, and doubling run throughout the work. At the beginning, we created a sort of imaginary taxonomy of all the ways in which he uses this device. We laid out all the places where you could see the same work in different mediums or with variations of color, as well as works created with an internal structure of repetition or mirroring, like the Ale Cans [1960], famously. It was fascinating to see how this relatively simple device extends and draws on decades of work, and we had a lot of fun imagining how we would put it in play in two institutions—two institutions that, as Scott said, have a deep history with Johns but that are fundamentally different. The Whitney focuses on modern and contemporary art, and is devoted to artists who live in the United States and are part of that culture, while Philadelphia is an encyclopedic museum, dealing with different cultures and time periods. We felt that the mirroring would work very well because the context would be so different.

SRWe didn’t set out to make a show with mirroring as a structuring metaphor or device. When we started, the struggle was to determine how to divide the show into two parts being staged simultaneously—it could have been paintings at one museum and works on paper at the other, or early at one and late at the other, but there was a moment when we’d dug so deep into the work that we saw this frequent and long-standing interest. After that revealed itself to us, it became useful as the structural armature of the show, though not as its theme per se. We seized on the notion that the two sites could echo or reflect one another.

AMcDHow do you think the exhibition will feel in the different context of each museum?

SRWell, as Carlos mentioned, we wanted to make the work accessible and alive to new audiences and to a younger generation of viewers. And at the Whitney we have a relatively young audience compared to other large institutions in New York. Our audience is used to coming to the Whitney to see emerging or mid-career artists, and we wanted the show to have a sense of curiosity, a sense of risk, a sense of drama about it. At the Whitney, in downtown Manhattan, we’ll see the work in that context, while in Philadelphia we’ll have the opportunity to look at the work alongside artists who were inspirational to Johns, such as Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, and Marcel Duchamp, whose galleries won’t be far away. And the extraordinary experience of that context will be different and distinct from the one more focused on young artists and questions of American culture, as Carlos said.

AMcDYou have some wonderful surprises planned. Would you share a few highlights, or describe a few specific rooms at each venue?

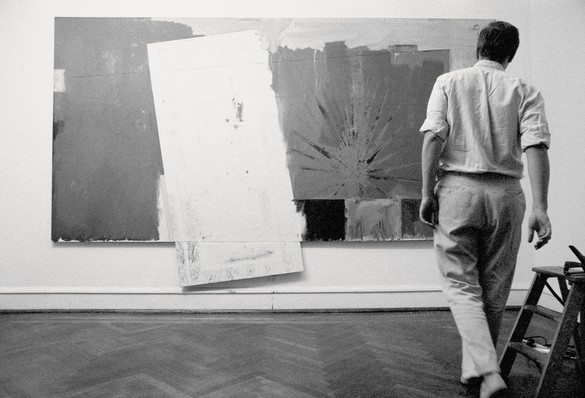

SRWhen we came up with this structure of two shows reflecting or echoing one another, the premise was that we would create pairs of galleries with different articulations of a shared idea. For example, we might focus on how Johns made exhibitions that he installed himself at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York, and a different Castelli exhibition will be re-created at each museum.

We also thought, for example, about how Johns has lived and worked in a variety of places throughout his career, and how those places have influenced and affected his art. At Philadelphia you’ll see Japan, and at the Whitney, South Carolina. So in each venue you’ll have a gallery examining this idea of place, but through totally different examples.

CBThat’s absolutely right. And Alison, a consequence of that is, there’ll be a moment in which the viewer will be going through these rooms and standing in front of the works, which is of course a truly important moment, but there’ll also be a moment when the viewer goes from one museum to another, or looks at the catalogue and imagines or remembers what was at the other place. That’s an integral part of the exhibition, that process of recalling, and the delicate balance between being present to the work and being absent from it, and that very absence propelling thoughts and the desire to see it. We understand that from a practical point of view there may be people who will only go to one of the venues, but we’re hoping that many people will be encouraged to go from one place to the other and in a way join both museums, connect both cities, and enjoy both experiences.

AMcDAnd what about Johns’s engagement? Many of the works on view are on loan from him. What does it mean to have his support?

SRWell, we couldn’t have done the show without his support. He’s the single biggest individual lender to the exhibition and he’s been an incredible abiding presence throughout this process. Carlos and I have met with him often and shared our ideas with him along the way. That said, he’s given us a tremendous amount of freedom to shape the show as we wished. Although he’s been quite curious and interested in our process, he hasn’t been directional, and that’s been liberating, letting us chart our own course through his work.

CBThat’s absolutely right. He’s very careful not to weigh in on the interpretation of the work. That’s an attitude he’s always maintained. It’s almost like he sees in his restraint the possibility of freedom for the viewer—that’s the way he is in terms both of individual works and of exhibitions. We’ve been given enormous and extraordinary permission to think freely about the work; it’s a great gift, and it duplicates the gift that he offers to the viewer by not getting in the way of interpreting the work.

AMcDYou’ve brought together works from the entirety of Johns’s long career, including recent works, and you alluded earlier to building on the existing scholarship. How do you see this exhibition as different from what’s come before?

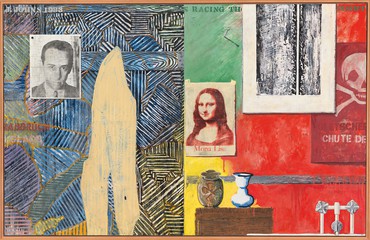

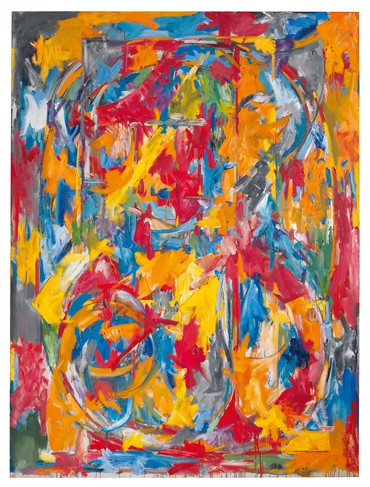

CBA long line of distinguished writers and curators have thought about Johns’s work. We benefited enormously from the scholarship of Roberta Bernstein, the catalogues raisonnés, and so forth. Still, we wanted to use our show as an opportunity to crack open some of the cemented layers of interpretation and allow people to relate to the work with a sense of spontaneity and rediscovery, or to feel the excitement that must have resonated when the work was first shown. To do that, it was important to us to put into question some of the categories that have coalesced around the reading of the work. We see a continuous process of transformation in the work—even on our most recent visit to the studio we saw an entirely new series, deeply connected with the logic of earlier work yet extremely different as well. That happens all the time. There’s certainly a linear timeline to the work, but there’s so much repetition—going back to earlier motifs, exploring them, sometimes twenty years or more after they first appeared. Skulls, for instance, are very present in the recent work and appeared for the first time in 1964. My hope is that our show offers a more complex understanding of how time and development happen internally for Johns.

SRI see the show as an extraordinary opportunity to present a living artist who is still making new work after sixty-five years. Very few artists have kept pushing the limits of their own previous practice over such a long career. And I hope it will be interesting for viewers to experience Johns’s continued sense of discovery and the emergence of new ideas, even in his most recent work.

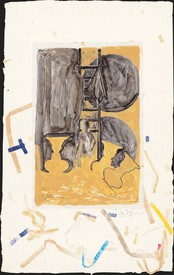

One of the things that struck both of us when putting together the final galleries of the show was just how bravely Johns is thinking about mortality in recent works that feature grieving or anguished figures, or the skeleton motif. It’s incredibly compelling to have an artist at this stage in his own life making such honest and complicated work about mortality and the human condition very broadly.

AMcDJohns is often described as a hugely inventive printmaker. How will that prowess be represented in the show?

SRFrom the very beginning we were committed to showing how prints have been generative in Johns’s work. Not only has he broken many boundaries in terms of the craft and technique of printmaking across the twentieth century, but printmaking has also informed the work that he’s done in other mediums. So prints are integrated in the different galleries with paintings, drawings, and sculpture, and there’s also a deep dive into prints at each venue.

CBAnd you know, Alison, one could say that Jasper Johns is one of the most experimental and innovative printmakers of our time, and that would be true. But in fact—and this will be clear in the show—we believe that he thinks through mediums. By that I mean that he uses printmaking to think about painting, and painting to think about sculpture, and sculpture to think about drawing, and so on. As the work progresses over time, it becomes more complex in terms of the interchangeability between mediums. So when you look at a recent drawing, you can’t always figure out how it’s made, and you can spend quite a bit of time simply trying to understand its material complexity. For Johns, materiality offers an immanent feeling that he traverses freely, which is an important aspect of the show. And in the two rooms devoted exclusively to prints, we’re also making a case about how chronology becomes complicated in the work, and how certain motifs repeat over time. We do that in two ways: at the Whitney we show a timeline that punctuates how chronology doesn’t really apply, and then in Philadelphia we’re using chance procedures to disorganize it.

AMcDDid you make any personal discoveries during the preparations? You both clearly knew the work very well before you began planning the show, but in working actively with the material for almost five years, probably you encountered something new, or maybe unlocked a new way of seeing the work?

CBWe discovered so much, Alison. We knew only the tip of the iceberg, and even now we know just a little bit more about the iceberg, because it’s a huge iceberg, right? Jasper Johns is one of the truly towering artists in art history, period. Once you look at the expressive span of his work, the virtuosity of his craft—both are truly enormous accomplishments. You can’t find many parallels in the history of art. There’s so much more to explore.

SRTo put a more specific point on it, for me one of the great surprises was an unknown trove of drawings that only came to light, frankly, with the publication of the catalogue raisonné of drawings during the process of making our show. Many works on paper had never been published or exhibited before, and were full of surprises and invention, dating back almost to the beginning of his career. In the studio we were able to dig into what felt like a secret corpus.

AMcDYou’ve put together an extensive book for the exhibition that includes sixteen authors, in addition to essays by each of you. I can appreciate how complex it must have been to put this publication together and I’m curious to hear how the book expands on the exhibition.

SRWe knew from the start that we wanted to open things up and let some fresh ideas blow through Jasper’s oeuvre. Of course we included some of the most distinguished authorities on his work, such as Ruth Fine and Jennifer Roberts, but by and large we chose authors who hadn’t previously written about the work. We felt the experimental nature of the show welcomed bringing a lot of different voices into the book from many generations and fields, whether it was art history, poetry, literature, philosophy, or artists themselves.

AMcDI feel like we could have a whole conversation just on the book, I must say [laughs]. What do you think has emerged from it? Is it exactly what you set out to achieve? Was there any voice that resonated in a way that you hadn’t anticipated?

CBCertainly, there are so many perspectives—we learned a lot through the authors, absolutely. My hope is that the reader will feel the same.

SRYes, and it’s interesting that the authors approached the work with a sense of respect but not necessarily reverence. Some of them ask hard questions or read the work against the grain, which challenges the established lines on Johns’s work. There’s a freedom in many of the voices in the book that will be surprising and will open up new pathways of conversation.

AMcDIn light of our current moment, how do you think audiences today might read the work, in particular some of the iconography of the early work? For instance, the flags could be thought of as a mirror of ourselves, and audiences today may start to read those works differently than they would have at the time of their making.

CBWe have an extraordinary room at the Whitney with two sequences of flags—a series of colorful flags and a series of black, white, and gray monochrome flags, which seem to be the somber counterpart or the critique of those colorful flags. So the symbol is there in all its glorious ambiguity, for all of us to reinterpret. Johns presents so much of the conflict, the strife, the successes and failures of American history in the postwar period, but there’s also the resilience of the work and the sheer joy of invention that speak so loudly today. For me he’s a figure of reconciliation, and I hope many people relate to his work in that way.

SRYes, I think that’s true, and he’s a symbol of staying power, of a long journey. It’s interesting—when we first thought of the flags and maps room, we imagined that the show was going to open on the eve of the past presidential election, and that it would have a very distinct resonance as a result. But of course to some degree that was naive, because these works will always mean something, at any point in history. He made some of them during the period of the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War, and since then they’ve been exhibited while America was engaged in different conflicts, or in partisan elections. They really are whatever the viewer brings to them at that moment in history. Similarly, a lot of people will connect the images referencing mortality to the covid-19 pandemic. Most of those works were made before the pandemic, but of course, if people have a new sense of mortality or have approached their lives in different ways over the past year, they’re going to bring that to the work, and that will make their experience more meaningful. Once again, Johns’s work becomes a springboard or a mirror for the feelings that the audience brings to it.

CBAs Scott is saying, the show itself will be a mirror, and nothing will be better for us than to know that we’ve created this possibility for the culture and the time to be reflected in the structure of the show.

Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and Philadelphia Museum of Art, September 29, 2021–February 13, 2022