Anne Baldassari entered the French Ministère de la Culture in 1983, where she was responsible for a program of support and innovation in contemporary art. In 1985 she joined the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, and in 1991 was appointed to the Musée national Picasso, Paris, where she was a curator, director, and then president of the museum until 2014. In 1992 she published the complete catalogue of Simon Hantaï’s work in the collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou. Baldassari curated Simon Hantaï: The Centenary Exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, in 2022.

“Absence, silence, for ten years now. Lost years?” Simon Hantaï often spoke in these terms, enjoying their tone of evasive condemnation.

And he did let time flow, let it ebb. White, the light of white, the influx of the white of the canvas honing the color one last time before making it disappear, raised painting to an unbearable pitch. A beauty such that it had to be refused. The overly effective discipline of this “doing” raised to the point of perfection. “I would prefer not to,” Herman Melville’s Bartleby repeats, eyes riveted on the soot-black wall across the yard.

S. H. inhabits a deserted place. From this inner exodus, in the empty room on whose walls canvases sometimes several layers thick recede into oblivion, he looks unseeingly through the window, book in hand. Turning toward something else, something discreet and restrained, he is clandestinely accomplishing work alien to profitable virtue, to fertility, to the predominance of the “I” in painting.

To all appearances, he is not working!

Unless here, at this moment, the whole body of work takes its meaning from a suspension of pictorial activity. “I would prefer not to.” 1

I met Simon Hantaï in 1984, in the highly formal context of a public commission for new stained glass for the Cathédrale Saint-Cyr-et-Sainte-Julitte in Nevers. Largely destroyed by bombing in July 1944, the building was still a construction site. The project was initiated by François Mathey, a former director of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris and the organizer of some of the city’s most important exhibitions of modern art, including retrospectives of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, between 1955 and 1980. Mathey was Hantaï’s foremost champion. He had shown as much in 1969 with a one-day exhibition of the artist’s monumental Études (Studies, 1968–71) in the great hall of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, an installation foreshadowing the wall project that Hantaï was working on for a school in Trappes.

Hantaï and Sam Francis—old friends—had been chosen by the French ministry of culture to conceive and execute the ambitious stained-glass project together. Francis was excited about it and even bought a house and studio in the rue Georges Braque, just opposite the house and studio that Hantaï, his wife Zsuzsa, and their children had moved into in 1979 after a reclusive decade-plus at Meun, in the forest of Fontainebleau. And so we went from one house to the other, and sometimes in procession all the way to the Manufacture des Gobelins, home to a giant model—a veritable building—that they had asked for and I had had made, one big enough for them to enter and walk around in, looking at the cathedral’s volumes and the relations between its spaces, testing materials, or setting designs in the open bays that were to contain their glass.

Hantaï had a long-standing interest in the stained glass that Jackson Pollock conceived for a chapel, ultimately unbuilt, designed by Tony Smith in 1950. Pollock’s Black and White Polyptych, from 1951, and the series of black paintings that followed it were an essential point of reference for Hantaï, who originally conceived his own stained-glass designs in black and white. Then they gradually became white on white, or, more precisely, completely transparent. An experimental glass that we worked on with the research laboratory of the Saint-Gobain company allowed Hantaï to apply physical principles to his models and drawings that had never been tried before: this glass was multilayered, and the layers had different refractive indexes, so that the glass, when exposed to light, acted like multiple prisms, generating colors directly in space—immaterial colors without a physical support. Hantaï took the idea for these colors, caused by contrasts among complementaries and the phenomenon of retinal persistence, from the fabulously poetic optical experiments described by Goethe in his Theory of Colors (1810). In about 1968, Hantaï had also observed the optical events created by Matisse’s slender black-and-white wall drawings at the Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence (1949–51), whose space they seem to tinge with purple. Matisse too had been a keen reader of Goethe; Theory of Colors was his bedside book when he was cutting into gouache-colored paper and using the play of these cutouts and cuttings against the white ground of the walls to conjure a “dance of space.”

The series of Tabulas that Hantaï occupied himself with between 1973 and 1982 was guided by this same project. Each of these canvases is covered entirely by a pattern of solid color, generating a white drawing in the areas left bare. The interlaced painted lines form a grid, regular but not rigidly so and marked by accidents throughout. The contrast between the white and the swaths of pure pigment induces intense optical effects, even “visions”: each patch, as Goethe would have predicted, seems to be tinted along its edge with its complementary color, generating haloes or incandescent sparks in the eye. The viewer of a big blue Tabula, then, may see superimposed over the actual grid a virtual one in yellow or bright orange, which sharpens his or her vision and, depending on the light, may seem to dance in front of the painting. The Tabulas thus propose a unique experience of pure vision. They are, in fact, machines for thinking about painting without any of the ballast of narrative or iconography.

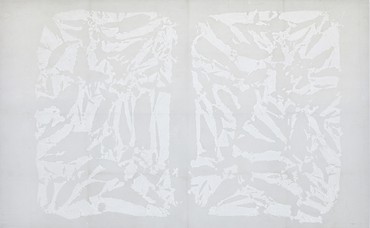

In 1982, Hantaï came as close as he could to capturing immaterial color with the Tabulas lilas series, which are painted in white on white—the white of the paint acting as a cold shade on the warmer white of the bare canvas support. When these large paintings are hung on the four walls of a gallery, the contrasts among their infinitesimally various tones saturate the space with a shade of lilac. This “sublime” result is generated by the chance interactions between the panels, the place, and the light suffusing it.

Hantaï imagined the Nevers stained-glass project as capturing light itself. He committed himself to it passionately, but in the end it was taken away from him and Francis for obscure “administrative” reasons. At the same time, following the limit experience of the Tabulas lilas, Hantaï stopped painting for nearly ten years. But he gradually made his way back to it. In his last work as a painter—he died in 2008—he saw the extinction of pigmentary color as the precondition for the appearance of a colored light that would fill space to the brim, a color with neither frame nor form. As with Pollock, his choice of black and white in these final pieces was designed to establish a purely theoretical status for the work.

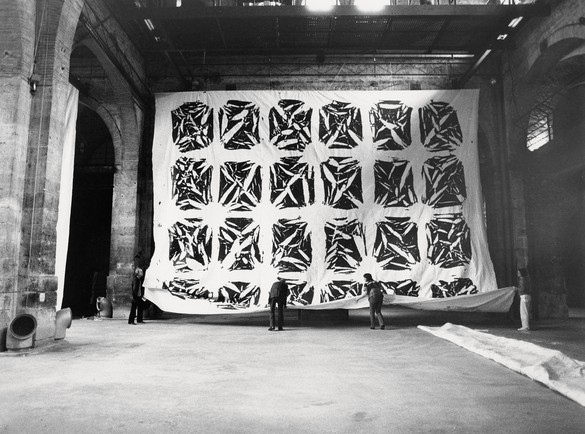

The exhibition LES NOIRS DU BLANC, LES BLANCS DU NOIR (The blacks of white, the whites of black) was conceived as an homage to the Nevers project, that rigorous quest to which I was the solitary witness. The show traced the line from Hantaï’s monochrome Études of around 1969 to the experiments in cutting and reassembling seen in the big black Tabula (1980), made for the exhibition of the CAPC in Bordeaux—the work from which, working piece by piece with a blade, Hantaï derived his first Laissées (1980–94)—and on to the ink-colored silk-screens of the late 1990s. The natural light diffused around Gagosian’s enormous Le Bourget space, a former aircraft hangar, by the curves in its concrete roof worked to induce the indescribable chromatic manifestations, simultaneously mental and spatial, that Hantaï sought. Depending on the weather and the time of day, the light might reveal to those prepared to wait for and apprehend them an evanescent purple cloud, orange-hued haloes, a yellow veil, a pink mist . . .

1Anne Baldassari, Simon Hantaï, Jalons. Collections du Musée National d’Art Moderne (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1992), p. 10. The phrase “I would prefer not to” is a quotation from Herman Melville’s Bartleby, the Scrivener (1853), to which Hantaï often referred in relation to Gilles Deleuze’s philosophical analysis of that story.

Simon Hantaï: LES NOIRS DU BLANC, LES BLANCS DU NOIR, Gagosian, Le Bourget, October 13, 2019–June 27, 2020

Artwork © Archives Simon Hantaï/ADAGP, Paris