Anne Baldassari entered the French Ministère de la Culture in 1983, where she was responsible for a program of support and innovation in contemporary art. In 1985 she joined the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, and in 1991 was appointed to the Musée national Picasso, Paris, where she was a curator, director, and then president of the museum until 2014. In 1992 she published the complete catalogue of Simon Hantaï’s work in the collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou. Baldassari curated Simon Hantaï: The Centenary Exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, in 2022.

The Italian Journey of 1942: Giotto, Masaccio, Picasso . . .

“Piero . . . hardly brushed”

At the age of twenty-three, Simon Hantaï made a statement in the Hungarian magazine Szinház. His words show that he had become used to speaking out as an orator in his capacity as president of the students at the Academy of Fine Arts and as a political activist who had been arrested by the pro-Nazi regime in March 1944 for a speech denouncing Hungary’s subservience to the German Third Reich.1 As World War II entered its last days, Budapest had witnessed unprecedented violence, with deportations, assassinations, and mass kidnappings targeting mainly Jews, deserters, conscientious objectors, intellectuals, artists, and left-wing progressives. The prophetic tone of Hantaï’s words expresses the shock felt by the survivors:

The process of decomposition that led humanity to the present destruction has been reflected in art as total destruction. This phenomenon of demolition has reached its peak. That is to be expected, for artists do not have the power to compensate for humanity’s lack of purpose. The progress of art has taken a new direction, which is not destruction but the birth of a golden age. Picasso has already begun this movement with some of his paintings. Building this new era is very difficult, especially when we ask the following question: has the next Giotto or Masaccio of our time already been born?2

In this short text, Hantaï appears to link the destruction of the world by war and the destruction of the old artistic order as common symptoms of the internal breakdown afflicting Western societies. While his terminology resonates with Spenglerian overtones,3 his prediction of the imminence of a “golden age” is closer to a Virgilian vision of history, in which rebirth comes at the end of a cyclical temporality.4

Modeling himself on the proto-Renaissance and early Renaissance artists Giotto and Masaccio, the young Hantaï believed that the mission of art was to anticipate this idyllic age by inventing a new aesthetic and moral representation of the world to come in painting. This Virgilian conception had previously been revived during the Renaissance and inspired a number of allegorical works, including Sandro Botticelli’s Spring (c. 1480)5 and Lucas Cranach the Elder’s eponymous The Golden Age (c. 1530) and Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden (1531).6 Renaissance artists revitalized this ancient theme in depictions of a utopian state of equilibrium and harmony sought by the great philosophical, religious, and political thinkers of their times.

Hantaï’s position is rather surprising if we consider the repeated calls for a tabula rasa made by the moderns ever since the time of Impressionism, calls to forget the lessons of the old masters and even to burn down museums.7 It was no doubt inspired by the artistic discoveries made in 1942 during his first trip to Italy8 with his fellow students from the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest,9 which took them to Florence, Siena, and Rome.10

Hantaï’s early interest in the art of the Renaissance was thus inspired by visits to museums and monuments containing works by the greatest painters of the period. In addition, studying the collections of early Western art at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest (Szépművészeti Múzeum), reflecting the dominant role of the Habsburg dynasty in shaping the destiny of European art since the Middle Ages, further stimulated his interest. He became familiar with the great masters of the Italian but also Flemish and German schools of painting. Zsuzsa Hantaï recalls the visits they made together during their early years as a couple: “In Budapest, we mainly saw the artists of the quattrocento and the Flemish . . . and Cranach!”11 Indeed, the spirit of mystical humility of the proto-Renaissance and the form of pictorial simplification that it initiated can be seen to have significantly inspired the works of Hantaï’s Hungarian period (1942–48). Born in “ancient times” in a rural village far from the capital, Hantaï stressed that for many years he knew nothing about art: “There is no painting. Just a few bad reproductions decorating the church.”12 Then, “In high school, in sixth grade, I enrolled in the optional sculpture course. . . . I was pretty much on my own, and the sculptor spoke to me, and [it was] the first time in my life that I heard anything about art and its social rules.”13

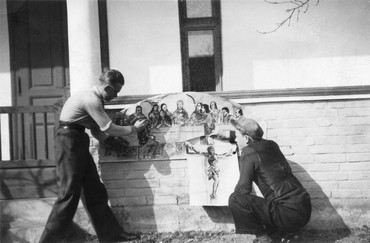

Hantaï’s canvases from this period, which were based on religious themes, are full of direct iconographic references to Renaissance painting. This is how he spoke of copying such subjects, which was an inescapable part of his early training: “A photo in Bia from my high school years. A Last Supper, manifestly, and a Cross. . . . Other Christs on the Cross and the Deposition. For a long time I didn’t know that painting could have other subjects, too.”14 This observation applies to the works of his Hungarian period, which, with the exception of his self-portraits, almost exclusively depict scenes from the Passion of Christ.

Introducing the effects of spatial perspective, modeling, and figure individuation, Giotto and Masaccio, who were the main objects of Hantaï’s interest, had inaugurated a form of pictorial objecthood that stands at the foundation of modernity in art. They went against the tradition of Byzantine icon painting, whose doctrine-based definition was expressed in formal models, rigid and closed outlines, chromatic symbolism, and a fixed representational code that reduced painting to a cryptogram, a copy of a copy.

The departures from this system experimented with by Giotto15 and pursued by Masaccio16 possess the particular charm of what comes between two worlds. Their movement between the flatness of fresco painting and experiments with perspective, between lifelike modeling and pictographic schematizations of the figures, and between elements taken from the contemporary context and a cryptic vocabulary constitute the framework for a pictorial reading of signs that oscillates between the known and the unknown, recognition and discovery of the real world. It is this alternating movement that makes their art so powerful as it gradually opens up to new forms of representation.

Heralded by Giotto and Masaccio, the modern period would seem, in Hantaï’s words in Szinház, to come to an end rather than to continue with “certain paintings” by Pablo Picasso. Picasso’s place here is that of an active liquidator of modernity. In Hantaï’s conception of the modern revolution, Renaissance precursors and Cubist liquidators stand opposite each other, respectively engendering and then pushing to extinction the principles of a painting rendered obsolete by the disasters of World War II.

An analysis of the work from Hantaï’s Hungarian period reveals the importance he attached to Picasso’s Blue Period in particular. As he saw it, the Spaniard’s adoption of this color, whose use by the Impressionists took on theoretical and manifesto-like connotations,17 was a way of choosing sides and asserting his position in the battle waged by the moderns at the beginning of the twentieth century. Contemporary critics, we may recall, described the Impressionists as suffering from “the terrible disease of blue.” They vilified Paul Cezanne for his “diseased eye” and accused Gustave Caillebotte of painting in a “tub of laundry blue.”18

In deciding to work exclusively with a generic blue in 1901 (until 1904–05), Picasso systematically pursued a process of monochromatic reduction that overturned the form-ground relationship and continued the revolution begun by the Impressionists. By denaturalizing and decontextualizing the subject, the monochrome directly challenged the mimetic modalities of painting. Monochromy provided the basis from which the pictorial process was rethought at the beginning of the twentieth century. After the “act of exorcism” of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), Picasso was in a position to lay down the terms of the Cubist method of deconstruction, analysis, and synthesis of form, from which he drew the polysemous, “elastic” and “paperistic” propositions19 of the years 1907–14.

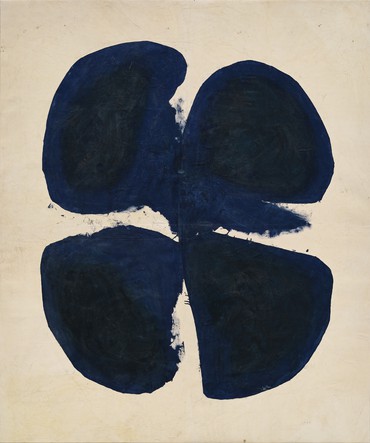

Is it possible to speak of Hantaï borrowing from Picasso’s Blue Period? Or even of him having his own Blue Period? Some of his works, painted in a singular and intense cyan blue bordering on turquoise, are undeniably related to a monochromatic reduction process inspired by Picasso. Executed between 1946 and 1948, three paintings in particular bear witness to the methods of transposition and citation he applied in assimilating the pictorial solutions developed by the old and modern masters.

Peinture (Jésus et les deux aveugles) (Painting [Jesus and the two blind men], c. 1946) shows the effect on his early artistic development of Hantaï’s study of the collections at Budapest’s Museum of Fine Arts. Its model was El Greco’s El Expolio (The Disrobing of Christ) (1579–80). Rather than offer a strict copy, which served as its model, Hantaï borrowed fragments from it and reassembled them in the manner of a collage. The triangle of figures at the center of El Greco’s composition, Christ and the two Roman soldiers, remains, but the positions, scale, and relationships have been changed. The voluminous necks, abyssal profiles, and polymorphous weave of hands deformed by the abrupt foreshortening of Peinture (Jésus et les deux aveugles) respond, point for point, to El Greco’s figures.20

This painting demonstrates the emergence of a theoretically underpinned monochrome in Hantaï’s painting. Here the blues take their shades from the bluish sky streaked with white in El Greco’s canvas, painted like a stiff brocade sheet with brittle folds. Its monochrome color; compact, curving composition; and enigmatic character are reminiscent of a major painting from the Blue Period, The Old Guitarist (1903–04)21 . Picasso’s blind beggar musician was also freely inspired by El Greco.

The episode of blindness that marked Hantaï’s childhood endows this painting, with its quotation from The Old Guitarist, with added weight. The experience of sensory deprivation triggered a hypersensitivity in the young man’s visual perception, playing an essential symbolic role in his life. The question of blindness suffered, accepted, or provoked became a key metaphor in his thinking. He took up Georges Dumézil’s analysis of the “qualifying mutilations” that conferred extraordinary gifts or virtues on the heroes of Indo-European myths. According to Hantaï, “You must gouge out your own eyes” in order to gain access to a pictorial making that is not dominated by the eye or by “the allurements of the eye.”22

The golden age to which Hantaï aspired in the magazine Szinház found direct resonance in the title given by the artist, in French, to his painting La Joie de vivre (The joy of life, 1946). The title is a direct homage to Henri Matisse, whose own Le Bonheur de vivre (1905–06) inaugurated a radical Fauvism.23 Hantaï also referred to the tactile style of Pierre Bonnard, whose work he discovered at the same time.24 Bonnard’s influence is perceptible in the tonal breakdown of Hantaï’s pictorial touch, which asserts itself from this point onward.

The strangeness of its composition and its evocation of legend link La Joie de vivre to the allegorical tradition of the Renaissance. The unity of the intense monochromatic field establishes a poetic universe that has its own special rules. The omnipresent, dreamlike blue, like the symbolism of the composition, relates to the world of the acrobats of Picasso’s Blue Period. The panoramic format of the painting, a big set piece that Hantaï worked on for months, evokes the narrative content of altarpiece predellas and the horizontality of the canonical treatment of episodes from The Last Supper and The Wedding at Cana. The rich iconography marking the history of these pictorial representations—notably by Giotto, Fra Angelico, Leonardo da Vinci, and Veronese—would seem to provide a pertinent angle for approaching La Joie de vivre.

Combining portraiture and still life, the painting is framed by three male figures, each obviously a self-portrait. A messianic trinity presides over a mystical dinner composed like a choreography. The two children as Pierrots, imported from the commedia dell’arte, evoke the intriguing hieratic quality of Jean-Antoine Watteau’s Pierrot (formerly Gilles, c. 1718),25 as well as the rarefied world of Cezanne’s Mardi Gras (1888).26 The pink and blue bouquet, meanwhile, borrows from Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s Boy as Pierrot (c. 1785).27 In all these respects, La Joie de vivre could be seen as demonstrating a claim to filiation with the great modern masters of color: Cezanne, Matisse, Picasso, and Bonnard.

The last painting before exile, Autoportrait (Self-portrait, 1948), presents the young painter’s three-quarter profile on a blue ground in flat tints.28 Here the medium of oils paradoxically reproduces the modeling effects obtained by Renaissance fresco painters in the use of a verdaccio-type preparation.29 Hantaï was also inspired by the phenomena of erasure and erosion of the pictorial surface and the patina of time, which imbue these frescoes with an aesthetic of disappearance and loss.

Finally, the expression of melancholy interiority, the blind gaze turned inward, toward an invisible object of contemplation, evokes ecstatic figures of saints or monks. In 2001 Hantaï wrote on the back of a photograph of Autoportrait, recently rediscovered in Hungary: “1948 Budapest / Piero, isn’t it? / hardly brushed [à peine effleuré] / 28.5 × 23 / tiny little thing, incomprehensible to me. It’s not a copy, so what then? I was sent [this] photo three years ago. How could I have done this?”30

While the painter may have wondered that this painting, which he did not recognize as his own, could even exist, he immediately discerned the aura of Piero della Francesca’s painting (“hardly brushed”). Without a doubt, the blues tending toward verdigris and the limpid manner and didactic profiles of Piero’s art assert their semantic originality in this self-portrait.

This fading of blue to green is what marks Hantaï’s work at the end of his Hungarian period. At the end of his Italian trip we find the mark of a blue that is once again intense, as in the Parisian paintings from 1949, Peinture (Petit nu) (Painting [Small nude]) and Baigneuses (Bathers). The Italian experience, during which, according to Zsuzsa, lack of space and resources meant that Simon produced very few pieces and worked only in a meditative mode, seems to have reinstated the option of a theoretical blue for thinking about and enacting painting.

The Journey to Italy in 1948: “Barbarians in the West . . . ”

With the exception of some ten paintings, including the ones mentioned above, few works from Hantaï’s Hungarian period have survived.31 In his hasty departure from Budapest in early May 1948, before pro-Soviet Hungary became isolated from Western Europe, he was able to gather only a few watercolors to take with him. Zsuzsa recalls that “he put them in his suitcase, in with his clothes.” At the beginning of the year:

Simon was promised a scholarship to study in Paris. Our French visas expired before we could get our passports. . . . So we left for Italy instead. . . . At that time it was already very difficult to leave the country, but we managed to take the last train in May 1948. The Iron Curtain came down behind us. We were alone! The train was empty. The army was patrolling the Yugoslav border. They took our passports. I was terrified. There was talk of missing persons . . . The war between Stalin’s Soviet Union and Tito’s Yugoslavia was about to break out. But in the end, it didn’t happen. Then from Yugoslavia we went to Trieste.We had left with nothing, we had absolutely no money left. When we told the ticket inspector that we didn’t have a ticket, all the Italians in the compartment clubbed together to pay for our trip. They were warm people.32

Simon Hantaï, too, would later recall the conditions of this hazardous journey: “In 1948, when we left Hungary, before the break between East and West was established, we crossed it in a train with practically no passengers. Zsuzsa and I were alone in one compartment, and the rest of the train was occupied by soldiers. At the Yugoslav border, more soldiers got on. There were armies on both sides of the border. That’s how we left Hungary. So you can imagine, when we arrived on the Adriatic, this wasn’t just ‘after the war,’ it was somewhere else. There were landscapes that we’d never seen before, totally unknown, and we were in an utterly incredible universe.” Zsuzsa remembered: “We arrived in [northern] Italy without any organization; we didn’t speak Italian. Impressions were flooding in! We were barbarians in the West.33

Hantaï’s exile into painting, the only country now possible, proceeded via Italy, a locus of art in the modern sense ever since the Renaissance. In the spring of 1948, the complexity of the political and cultural climate in Italy—a country where for a thousand years history and the history of art had meshed, a place haunted by the dead worlds of Greek and Roman antiquity, the inventions of Christian, Renaissance, and Baroque art, a nation emerging from the collapse of a fascism that claimed to be “futuristic,” torn apart by the disasters of a war that had willed absolute eradication—must certainly have helped hone his awareness of the contemporary situation.

“1948 Italy 6 months.”34 During the late spring and summer of 1948, Hantaï crossed the peninsula from north to south, then from west to east, his journey taking him from Budapest via Trieste35 to Forlì, from Forlì to Venice, from Venice to Rome, from Rome to Naples, Pompeii, and Capri along the coast, then inland from Rome to Siena and Florence, from Florence to Ravenna and from Ravenna to Venice by sea. He no doubt returned to Rome before leaving Italy for France toward the end of September.

This journey was mapped over that initiatory trip of 1942, which took place in a completely different setting and world. The two experiences were marked by the contrast between the teeming postwar Italy, liberated from Fascism, and the country in the early 1940s, a member of the Axis, bellicose and heavily regimented. It is worth noting that Hantaï’s itinerary partly reiterated the one he had taken earlier. Once again, the painter explored Rome, Siena, and Florence and revisited their great sites in search of the works that had made such a powerful impression before.

According to Zsuzsa: “We went first from Trieste to Forlì, south of Venice. And there we spent a night and slept on the ping-pong table in the local Communist Party cell. Then we went to Venice to get some money. . . . I think we got the money on Piazza San Marco, at the Caffè Florian, which was very popular with North American tourists at the time. We didn’t stay in Venice. Simon wanted to go straight to Rome.”36 The sum mentioned here enabled Simon and Zsuzsa to reach the capital in early May 1948.

In Rome, Hantaï joined with the group from his studio at the Académie des Beaux-arts, who had received scholarships and left Budapest in 1946: “It was a period when Simon was making up for lost time with his friends. It was a dangerous and tragic time, politically and humanly, from which we had miraculously escaped on the last train. . . . There was Antal Bíró,37 Poldi,38 Judit [Reigl],39 Sándor Zugor.40 As soon as we arrived in Rome, Simon threw himself headlong into these discussions. He wanted to learn everything in these big, big discussions. His friends Judit Reigl and Poldi later went back to Hungary. They had no idea that this was a trap that was closing in on them. Judit got out again, and it was dangerous but much later.”

The group also made friends with the American Sue Jaffe41 and the Hungarians Imre [Amerigo] Tóth,42 a sculptor, and Péter Szervánszky,43 a violinist. “In Rome, we were at the Collegio. It was a small castle on the Via Giulia; King Matthias Corvinus [of Hungary] had bought it in the sixteenth century, and scholarship holders were housed there. But the institution welcomed us even though we didn’t have a valid scholarship. We were given food, and in the months that followed we managed to keep going, we drank water or milk and ate figs.”

The climate of intense debate described by Zsuzsa suggests that the advent of the pictorial “golden age” to which Hantaï aspired was at the heart of their shared concerns. His friends had already been in Europe and Italy for more than two years and had stored up thoughts, experience, and knowledge about new artistic trends. Shortly after his arrival in Rome, Hantaï took part in the Mostra Artistica dell’Accademia d’Ungheria, organized at the Palazzo Falconieri from May 26 to June 12 by Tibor Kardos, then director of the Hungarian Cultural Institute. He exhibited the watercolors he had brought with him from Budapest.44 The writer Norman Mailer happened to be visiting Rome at the time. He met up with Zsuzsa’s American students and artist friends and visited the exhibition at the Palazzo Falconieri. There he acquired all of Hantaï’s Hungarian watercolors.45 This unexpected sale financed the trip that took Simon and Zsuzsa to Paris at the end of the following September.

In Rome, as they were not officially scholarship holders, the Hantaïs stayed more or less secretively at the Hungarian Cultural Institute: “We had a small room behind Antal Bíró’s studio. A small room to sleep in. That’s all the territory we had. Simon couldn’t do anything there. He chatted; he was happy.” Zsuzsa remembers that this room “overlooked the Tiber.” Indeed, the Palazzo Falconieri, built by the Baroque architect Francesco Borromini, stands on the banks of the river, where, around the garden, a U-shaped courtyard connects several buildings dominated by a monumental Palladian loggia.

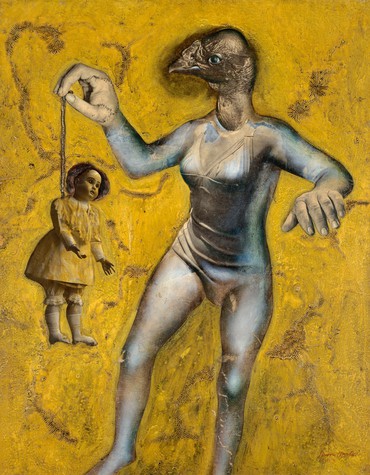

It is to be noted that at the top of the two pilasters framing the Via Giulia facade Borromini had placed hybrid sculptures, unusual sphinxes (sphinges in French) combining an eagle’s head with a female bust.46 This figure is directly reminiscent of certain montages from Hantaï’s Surrealist period, such as his paintings from 1952–53 incorporating collages of objects and skeletal fragments and featuring an identical hybrid creature: a sphinge with a bird’s head and a woman’s body.47 This visual citation gives an idea of the influence on Hantaï’s later work of the Roman models he saw in museums or observed in everyday life during his time in Italy. We can see the powerful impact that the Renaissance collections, ancient ruins, and modern monuments that he saw on his travels around Italy had on shaping his vision and sensibility, and on his future references.

An album of photographs retraces the main stages of the Hantaïs’ stay in Italy, from start to finish, in the company of their band of Hungarian friends.48 The group can be seen posing in the courtyard of the Hungarian Cultural Institute or strolling through the Roman countryside. Zsuzsa recalls the evenings they spent on the Capitoline Hill (Piazza del Campidoglio), whose urban scenography, buildings, and sculptures were designed by Michelangelo: “Together with friends, we used to go to the Campidoglio in the evenings. We’d go there to daydream, chat, and soak up its very special atmosphere. Its architectural perfection seemed musical to me. Musical! In the middle, there’s the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, and on the steps, the Rivers [sculptures of the Tiber and the Nile]. And all this in the evening under the moonlight.” The young “barbarians” exfiltrated from Hungary, survivors of the war, were astonished by this disconcertingly urbane and civilized lifestyle: “Once, we went to the French embassy, which was on the corner, not far from the Palazzo Falconieri. They served us tea in white gloves!”

Zsuzsa hit it off at once with Goliarda Sapienza, a young film actress from a family of anarcho-syndicalist activists who was fascinated by the Hungarian political experiment. Together they walked around Rome “hand in hand,” conversing only in English. Goliarda would later make a name for herself with the publication of her important book The Art of Joy.49 As for Simon, he visited contemporary art exhibitions with his group of friends and grew more familiar with an Italian situation fraught with tensions not unlike those tearing Hungary apart at the time.

On March 30, 1948 (the exhibition ran until the end of June), the V Quadriennale, or Rassegna Nazionale d’Arti Figurative, opened in Rome, reviving an event first held in 1931, under Mussolini, with the aim of promoting Italian national art and, more specifically, realistic figuration. In Italy the Fascist ideology that had imposed its principles on cultural and artistic life since the 1920s still had deep roots in political institutions and pressure groups but was now meeting with public opposition. The most virulent critics were pro-communist intellectuals close to the Italian Communist Party. The Zhdanovian doctrine of Socialist Realism, however, which was rampant in both Moscow and Budapest, also governed the discourse of the Italian communist left. A few years apart, on both these seemingly opposing fronts, there were escalating calls for realism and mimetic figuration in painting. Modern art and its most contemporary advances, including abstraction and emerging Abstract Expressionism, were in most cases misunderstood or denigrated as avatars inspired by the bourgeois individualism promoted by American capitalism.

The opening of the Quadriennale was the artistic event of the spring and the subject of much comment and controversy in the press. For the first time since the rise of Fascism in 1922, a large-scale exhibition at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Valle Giulia, Rome, set out to take stock of trends in contemporary art.50 The press, disappointed by the cautiously academic nature of the event, composed headlines such as: “Difficult for Visitors to Distinguish New Art from Old.”51

For Hantaï and his friends, however, the exhibition was an opportunity to discover the artists of early Futurism:52 Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Enrico Prampolini, Luigi Russolo, Gino Severini, and Ardengo Soffici were given a retrospective presentation in room 10, with some thirty works. There were also paintings by Amedeo Modigliani and Giorgio Morandi, as well as abstract works by Alberto Magnelli. The most heated controversy concerned the presentation and rise of abstraction. As one critic wrote: “Abstraction? At the Quadriennale—which is the exhibition of ‘Figurative Art’—the abstracts are welcomed in their numbers and hung on the picture walls to the most abstract disinterest of visitors.”53

Zsuzsa recalled: “We stayed in Rome for a while, then traveled around Italy. We often hitchhiked for lack of money. We slept on the roads, under bridges.” A boat trip took Simon, Zsuzsa, and the Fine Arts group to the Amalfi Coast. They sailed along the coast past Sorrento, Positano, and Amalfi, stopping off at Capri. They strolled among the ruins of Pompeii and no doubt visited Naples and the Museo Archeologico.

Back in Rome, they set off again to visit Siena: “In Siena, we slept in an ‘Ente d’Assistenza’ or a ‘Ricovero dei Mendicanti.’ We had the city, the square, the Lorenzetti, all to ourselves, for a whole day. And one morning, at 5 o’clock, a truck took us to Florence.” This journey confirmed Hantaï’s deep interest in proto-Renaissance painting. In Siena he studied the innovative frescoes by Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti and reflected on the Basilica of San Francesco’s austere two-tone gray-and-white geometry, which shapes the perception of its interior space. The repetitive accidentality of the multicolored stained-glass windows gains added power from these surroundings, a principle that would inspire him in the late 1980s, when he worked on stained-glass windows for Nevers Cathedral.54

In Florence, at the Galleria degli Uffizi, Hantaï was deeply moved to see again Giotto di Bondone’s Madonna degli Ognissanti (c. 1306), flanked by two post-Gothic Madonnas by Cimabue and Duccio, a milestone in Giotto’s proto-Renaissance revolution. The blue-black hue of the Virgin’s ample cloak would become a semantic key to the Mariales series (1960–62), the first paintings to use “folding as method.” In the church of Santa Maria del Carmine, he studied the compositions of Masaccio and Masolino di Panicale, which cover the walls of the Brancacci Chapel and interact with the light. The impact of these unbounded frescoes would be felt in the monumental installations of his later Études (1968–71) and Tabulas (1972–76).55

At the Museo San Marco, formerly a Dominican convent, he contemplated Fra Angelico’s frescoes glowing in the white plaster cells and altarpieces, such as The Deposition of Christ (1423–32)56 and The Last Judgment (c. 1431), with their lapis lazuli tempera. To works such as these we can link the paintings from the 1950s of which Hantaï kept only fragments that he slashed with scissors, all of them blue and some bearing pictographic motifs of trees in a Byzantine or proto-Renaissance style. The 1950s onward also saw Hantaï’s blue become colder, its intense shade of azzurrum ultramarinum (literally, “blue from beyond the sea”), lapis lazuli and ultramarine, now tending toward violet or black, away from the warm oriental blue of the Hungarian years, with its hints of green, jade, and turquoise. A symbol of the mystical, sacred nature of painting during the Renaissance, this precious pigment, sometimes called “Marian blue,” was mined from the volcanic stones far over the seas.

From Florence, the group traveled to Ravenna, where a visit to the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia (fifth century) constituted an aesthetic experience whose reverberations were to spread through Hantaï’s work for decades to come.57 The small openings of this heavy archaic edifice are filled with milky, pearly opaque alabaster slabs that are set ablaze by the sunset. Placed above the blue, black, and gold mosaics, these slabs turned bright orange by the sun vibrate in the darkness of the basilica, provoking a violent chromatic contrast. In 1997, Hantaï titled an earlier large-scale painting À Galla Placidia (Écriture grise) (To Galla Placidia [Gray writing], 1958–59) in homage to the early Christian mausoleum. The golden cross at the top of the starry lapis lazuli mosaic in the cupola can be seen to inscribe its mnemonic image in his écriture grise.

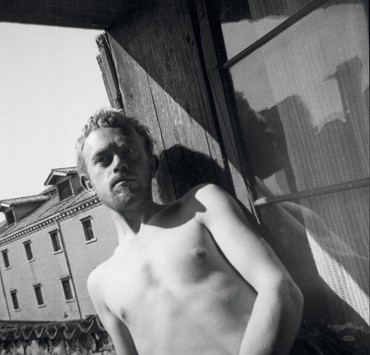

At Marina di Ravenna, the group embarked for Venice on an old fishermen’s boat, sailing up the Adriatic coast to the Serenissima. This is how they arrived in Venice, by sea. They stayed there for two weeks, and with the help of Judit Reigl’s English friend Betty Anderson, they assembled at Casa Frollo, on the island of Giudecca, a historic refuge for artists and outsiders. The small square window of their room, located in the building’s attic, had a view over the Giudecca Canal, and Simon and Zsuzsa would gaze at the sunsets and the incessant movement of boats on the canal. Their mirroring portraits are framed by this window, dispensing light in this “room with a view.”

That summer saw the Venice Biennale reopen for the first time since it had been suspended in 1942. Artists, critics, and museum directors from all over the world flocked to the twenty-fourth edition. Hantaï discovered a turbulent postwar art scene of which he knew almost nothing. The major exhibition dedicated to the French Impressionists took pride of place. Modern European painting was represented by the Pablo Picasso retrospective, featuring for the first time Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and Guernica (1937). Georges Braque was exhibited in the French Pavilion and won the Biennale’s Grand Prize ex aequo.

One of the most remarkable events in Venice was the presentation of the private collection of the young American Peggy Guggenheim.58 It was exhibited in the Greek Pavilion in a display designed by architect Carlo Scarpa.59 Photographs of various phases of the hanging and then of the opening from the Peggy Guggenheim Foundation archives show the importance of the modern paintings and sculptures exhibited there.60 For young artists in search of reference points and painting lessons, the exhibition played a crucial role.

Advised by Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, and Man Ray, who immigrated to the United States during World War II, and endowed with substantial financial resources, Guggenheim acquired emblematic works by the greatest modern masters of the interwar period. With 136 works, her exhibition covered the major movements of Cubism, Futurism, Suprematism, Abstraction, Dadaism, Surrealism, and more, with major works by Jean Arp, Giacomo Balla, Constantin Brancusi, Alexander Calder, Massimo Campigli, Salvador Dalí, Giorgio De Chirico, Theo van Doesburg, Max Ernst, Alberto Giacometti, Jean Hélion, Wassily Kandinsky, Fernand Léger, Kazimir Malevich, Joan Miró, Piet Mondrian, Francis Picabia, Pablo Picasso, Gino Severini, Yves Tanguy, and Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart. The American school was also represented, with works by William Baziotes, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Clyfford Still. Pollock’s painting would play a decisive role in the later development of Hantaï’s work.61

The shock wave of this early discovery of Pollock’s work would take some time to submerge and subvert Hantaï’s visual world. Among the five Pollock paintings exhibited in Venice were four works from his Surrealist period: The Moon Woman (1942), Two (1943–45), Untitled (1946), and Circumcision (1946). The fifth, Eyes in the Heat (1946), was important in that it demonstrated the drip technique Pollock began using in 1945. It can be considered a direct source for Hantaï’s works, including Duchamp effacé (1951–60), Saint François-Xavier aux Indes (1958), and Les Larmes de saint Ignace (1958),62 which belong to the pivotal period that saw him gradually move away from Surrealism and toward gestural automatism (1951–58).

Paris, September 1948: An Exile in Painting

When he arrived in Paris in September, Hantaï was in search of artistic approaches that resonated with what he had been pursuing during his formative years at the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest. The visual qualities of the paintings discovered during the trip to Italy would infuse his research during his early years in Paris, from 1948 to 1950. The photos taken in the autumn of 1948 in the hotel room that he and Zsuzsa shared on the Île de Saint-Louis show him painting on the seat of a Thonet chair, which he used as a table and palette. Around him, pinned to the patterned wallpaper, is an accumulation of small studies, postcards, and reproductions of works by the masters. Their superimposed motifs literally carpet the space of the room, forming a visual continuum that anticipates the future installations of “the last studio” (1982–85).

When, in 1946, Hantaï asked in Szinház, “Has the next Giotto or Masaccio of our time already been born?” he was indeed framing the moment as one of artistic revolution, explicitly drawing inspiration and setting himself apart from both the old masters and the most recent moderns. His question expressed his ambition to be, at midcentury, one of those new precursors whose mission was to reinvent the world of painting. Daily visits to the Musée de l’Homme and the Louvre and his ongoing study of the modern masters Cezanne, Matisse, and Picasso formed the multidimensional axis of his exploration of the Parisian scene. From 1952 onward he turned his attention to André Breton and the Surrealists.

In autumn 1948 Hantaï picked up where he had left off upon departing Budapest six months earlier. Once again it was a question of developing the monochromatic method and the deliberate use of that combat blue initiated by the Impressionists rather than a genuine interest in Picasso’s iconographic universe. “Simon,” recalled Zsuzsa, “was moved by the ‘spiritual’ character of Picasso’s painting,” a quality whose absence he deplored “in contemporary painting.” For Hantaï, the same pictorial spirituality linked the Blue Period to the altarpieces and frescoes of Giotto, Masaccio, Piero della Francesca, and Fra Angelico. Color was the link. Color was his.

Peinture (Petit nu), which Zsuzsa remembers Simon and her calling “the little Cranach,” depicts a standing, cross-legged female nude, referring to medieval figurations of the theological, cardinal, or monastic virtues that decorated religious buildings.63 Representations of Chastity, Purity, and Innocence stem from the ancient tradition of the Greek “modest Aphrodite,” emblematically represented by the Medici Venus, which he saw at the Uffizi in Florence.64 The aesthetic of Peinture (Petit nu) in fact evokes faded Renaissance frescoes such as Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (c. 1425).65 The “modest” posture of the model ties in with the spirit of this iconographic tradition. However, indirect quotations from the the sixteenth-century works of Lucas Cranach the Elder, such as Venus in a Landscape66 or Venus,67 seen in the Louvre, give it a more suggestive dimension. Sharing the same atypical elongated vertical format, these canvases embodied the powerful aura of the figures represented. Their flat, abstract, indefinite space presents an infra-division of their lower part, which designates rather than represents the ground.

An intense turquoise blue envelops the figure in Peinture (Petit nu), denying the existence of any material context. It is the significance of the model that is indexed here rather than its corporeality. The flatness and absence of modeling, reinforced by the monochrome background, give it an emblematic quality. This mute sign represents only itself. The aura of the image is like a reminiscence of Picasso’s watercolor Mother and Child (1905) in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. Painted in an intermediate manner, between the Blue and Rose Periods, this black-wash watercolor in indistinct pink, suspended in the obscure, undefined limbo of painting, embodies the tragic passion of maternity. It is like a negative of Peinture (Petit nu), sharing yet inverting its subtle nuances. In both cases monochrome is used to create a new semantic relationship between form and content.

The same problematics of quotation can be found in the large painting Baigneuses, executed at the same time. Here nine female figures, as mute and chaste as those of the “little Cranach,” line up against the painting’s horizontal background. It takes its characteristics from a mixture of The Three Graces (1531) by Cranach the Elder, seen in the Louvre; Cezanne’s Large Bathers (c. 1894–1906); and Botticelli’s Spring (c. 1480). The color blue remains strongly present in the pictorial space, but the monochrome protocol is abandoned. Cyan for the sky, turquoise for the expanse of water, yes, but green takes over the pictorial surface everywhere else to create a vast undulating landscape indexed by three pictographic trees.

The painting appears to be encrypted in anagogic mode via the numbers nine and three (nine figures, three trees, three primary elements: air, water, earth) and could thus refer to the hierarchy of angels subdivided into nine angelic choirs and three triads, as well as to the symbolism of baptism or the myth of the cosmic tree of life. These symbols have generated a complex iconography in Christian painting and decorative arts ever since the origins of the religion. Peinture (Petit nu) and Baigneuses, painted by Hantaï during the period when Zsuzsa was carrying their first child, born in 1949, could be a kind of prediction, blessing, or protection.

The Blue Eye of the Fold: “P. d. Francesca, Masaccio, Giotto’s Blue‑Black Madonna at the Uffizi”

It would seem that these few words by Simon Hantaï, noted after the event, were all that remained and all that he recorded of his trip to Italy in 1948.68 In the meantime, with the exception of trips to Colmar (Grünewald), Vence (Matisse), Aix-en-Provence (Cezanne) and Italy (Venice Biennale), the painter never left the Île de France (Paris, Meun). Thus, for Hantaï, all that can be said of his earlier Italian travels can be summed up in the ambiguous blue-black color of the mantle of Giotto’s Madonna degli Ognissanti.69

The painting, an altarpiece, was executed at the very beginning of the trecento, in tempera and gold in the Byzantine and Gothic manners, for the Chiesa di Ognissanti (Church of All Saints) in Florence, under the aegis of the monastic order of the Humiliati friars.70 When this order was banned, Giotto’s altarpiece was moved from one place to the next, entering the collections of the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence in 1919. Since 1937 a room in the museum that brings together the Maestà (Madonna in Majesty) altarpieces by Giovanni Cimabue (c. 1290–1300),71 Duccio di Buoninsegna (c. 1285),72 and Giotto di Bondone (c. 1306) has presented this pivotal moment in the pictorial revolution of the proto-Renaissance period, at the turning point where the duecento became the trecento.73 The installation of the three Madonnas in Majesty was perpetuated and made visible during Hantaï’s two successive visits to Florence in 1942 and 1948.74

Their confrontation here reveals the profound change in stylistic, intellectual, and chromatic definition that Marian iconography underwent during this period. Blue, so devalued in the Greco-Roman West that no specific term for it appeared until the Middle Ages, between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, came to the fore symbolically only with the emergence of a cult specifically dedicated to the Virgin Mary. A comparison of the three Maestà paintings highlights the innovative conception at work in each one. The treatment of the figures moves from a codex of iconic art to sketches of painted portraits. The architecture of the Virgin’s throne evolves from a precious pedestal to a seat inscribed in material space. The strong symbolic hierarchy of the dimensions of the figures of angels, saints, and monks around the Virgin fades away and comes closer to objective dimensions. Finally, the chromatic resonance of the Virgin’s cloak increases visually in power and changes in nature.

We can thus observe changes in the use of color among these three panels that are a few decades apart. Cimabue covered the wooden background with gold leaf, over which he applied a stereotyped pattern of two-tone striations in red for the dress and dark blue, almost black, for the mantle. The drawing of these striations evokes the relief of the garment’s folds. The gold color, coming from inside the painting, is used to mark their highlights, as would a light source projected from the outside. The altarpiece stands like a screen stretched between two worlds, between mystical light and physical light.

Duccio completely enveloped the Virgin in the draped canvas of her cloak. The blue becomes lighter, tending toward ultramarine. Treated as a single, broad flat tint, it erases rather than emphasizes, as in Cimabue, the volume of the barely sketched body of the Virgin, whose modestly averted gaze evokes the virtues of virginity and chastity. This opaque, amorphous color, combined with the pose, prefigures the posture of the Virgin of Humility, who would soon (after 1348 and the Black Death) replace the Virgin in Majesty in religious iconography.

The direct gaze of Giotto’s Ognissanti Madonna emanates from the face with its carmine modeling. Its blue-green-brown hue resonates with the velvety depth of the Virgin’s blue-black cloak. A highly saturated color in the medieval mode, with the tiniest tinge of green, almost a Prussian blue avant la lettre.75 In its density and darkness, this blue-black remains a “color of affliction” in the iconographic tradition of grieving Virgins doomed to eternal mourning.76

The Marian cult bestowed a singular symbolic value on the color blue. Celestial, divine, mystical blue infuses proto-Renaissance painting with its polysemous significance: the fresco blues of Giotto, Piero della Francesca, Fra Angelico, Masaccio, and the Lorenzettis, who were constant references for Hantaï, color the drapery around gold-haloed sacred figures with ineffable nuances. These blues, which literally body forth the Virgin, form the very pictorial substance of the Marian iconography of the trecento and quattrocento. These clusters of blue drapery merge with the very object of painting. To paint is to represent the folds that give shape to the body. Initially interstitial, reserved for adornment and decoration, blues gradually colonized the pictorial surface, then the heavens, and finally replaced the mystical gold grounds. From then on, gradations of blue filled the canvas from one side to another, uniting within a single dimensional sphere both the biblical scene in the foreground and the horizon to embody the infinity of an original spiritual space.

Hantaï was constantly examining his paintings in relation to the works of the old masters. Observing a Meun (1968–73) “put to one side” in his studio, he noted: “I’ve been looking at it ever since with the same incredulity. And then, as so often, the play of references to the past to come. Enguerrand Quarton’s Coronation of the Virgin (1453–54) in Villeneuve-lès-Avignon. Beneath the red folds, the blue mantle, painted in contrast, barely modeled. Flattened, cut, and spread out. The very subject of this painting . . . There’s a Meun under that. Or on it.”77 Beneath the red and gold garment bearing the papal colors, enveloped by the incarnate mantle of Christ-God, the Virgin hides the bright blue fabric of her cloak. It appears at the edge of the fingers on the right, along the divine mantle to the left. It flows and leaks in the center, flaring out broadly beneath the feet of the Virgin, who seems to be crushing its folds, as she would a snake.

The cold blue of the lapis lazuli forms a corolla on the white ermine cloud that serves as the scene’s pedestal. The painting was never intended as a catechism to illustrate the foundations of Catholic dogma. The strangeness of its composition was strictly in keeping with the commission, which was conceived as a theological exposition of the thinking of the Carthusian order.

The “blue revolution”78 was indisputably linked to the consolidation of the Marian cult within the sphere of doctrines and precepts elaborated by medieval Catholicism. In Europe, blue was a “barbarian” color marked by Germanic culture:

The vocabulary itself underlines the Romans’ distrust or disinterest in the color blue. To say ‘blue’ in classical Latin is not an easy exercise. There are many words to choose from, but none of them really stands out. What’s more, they’re all polysemous and express imprecise nuances. For example, caeruleus, the most common word for blue in imperial times, originally referred to the color of wax. The boundaries between blue and black, blue and green, blue and gray, blue and violet and even blue and yellow remained blurred and permeable. Latin lacked one or two basic terms that would make it possible to firmly establish the lexical, chromatic, and symbolic field of blue, as was done without any difficulty for red, green, white, and black. This imprecision in the Latin lexicon of blues also explains why, a few centuries later, all Romance languages were obliged to call on two words foreign to Latin to build their vocabulary in this color spectrum: on the one hand, a Germanic word (blau), on the other, an Arabic word (azure).79

Hantaï’s Germanic, Swabian, and Catholic ancestry—his family emigrated from southern Germany (Bavaria) to Hungary in the seventeenth century80 —is an essential aspect of the painter’s biography, one to which he continually referred and which, despite successive exiles, he considered a constitutive characteristic of his genealogical, intellectual, and spiritual identity. He insisted on the linguistic and cultural compactness and resilience of his Catholic-Swabian sphere of belonging: “He belonged to a community from southern Germany, of Swabian origin, Catholic, who had immigrated long ago but remained alien to the native population, itself of Protestant faith. He speaks of Bia as a place where worlds separate: different languages, different houses. ‘Even the vines grew in different ways.’”81

Beginning in the eleventh century, Hungary developed a singular cult of the Virgin Mary, making her queen of the kingdom. The “Marian Way” that runs through the country links towns dedicated to the Virgin (including Máriapócs, site of the miracle of the icon of the Weeping Virgin) to the network of convents, churches, and votive chapels of Eastern Europe. The religious ceremonies to which Hantaï refers in his remarks relate to the Assumption processions, held during the octave of August 15,82 during which local populations adorned their native villages with intricate floral decorations: “At each religious festival, there was a broad carpet of flowers in front of every house throughout the village, with flowers picked from the fields—poppies, cornflowers, lily leaves and other things with which to make patterns, with no limits to the imagination. A wide carpet of flowers was laid out for the religious festival, the procession to take place on. . . . And then it would come, and in passing over it, they made it disappear, and it was made anew every year. This left a deep impression on me as a child.”83 This ephemeral decoration was accompanied by wall paintings in blue and yellow, which marked this high point of the religious year, and summer festivals continued for some time.

Hantaï returned repeatedly to the initial sensory shock of his exposure to the chromatic nuances of the Maestà in Florence and explicitly associated it with an indigo-dyed cotton apron, the garment of his mother, Anna: “the immense, massive blue-black dress of Giotto’s Madonna, for me an extension of my mother’s folded indigo-black apron.”84 From 1960, with the conceptualization of “folding as method,” the semantic association between the mother’s apron, blue, and folding became a structural element in Hantaï’s painting. It forms the signifying syntagm at the heart of his practice.

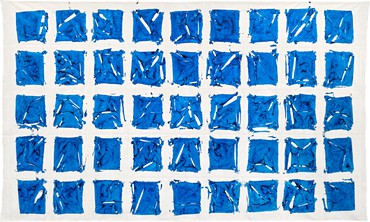

As the opening of the catalogue for his retrospective exhibition at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in the Palais de Tokyo in 1976, Hantaï juxtaposed a reproduction of an indigo-blue Tabula, still folded, with a photograph of his mother, Anna. The pattern of the square-ironed festive apron she is wearing is identical to the one in the painting.

The analogy laid out by Hantaï in his introduction to the retrospective of his work places maternal finery at the epicenter of the productive procedure of folding as method.85 The paint, like the apron, is manipulated by successive folds, inscribing its weft, its imprint, its design on the canvas. This simple piece of indigo-blue fabric, which the work literally presents, became the emblem of his work in progress, linking him to an age-old family and cultural tradition. It is not embroidery, lace, or a carpet; it does not belong to the decorative sphere. It is simply the play of light and shade, something that emerges only to fade away. A metric of energy. A gift.

The biographical note that Hantaï uses this picto-collage to articulate in this 1976 catalogue is spelled out in a cryptic note at the end of the book: “Simon Hantaï was born in Hungary on December 7, 1922 (cf. plate 2). He has lived in France since 1949.” Yet the “plate 2” cited in parentheses here is precisely the one that reproduces the photographic portrait of his mother. This direct but singular reference is supported by a legendary fact reported by Hantaï: it was said that in this photograph Anna Handl86 was pregnant with her son Simon.87 For Hantaï, the image was then also, quite literally, an Annunciation, prophesying his own coming into the world, as if moved, carried, and birthed by the womb-like, squared, tabular apron of a painting in gestation, to come. A Tabula not unfolded.

Reviewing some of his work before donation to a museum, Hantaï renamed some of his early paintings, notably titling a large earthy-purple work . . . del Parto. Tabula (1975).88 The title refers to Piero della Francesca’s Madonna del Parto (Madonna of parturition, c. 1460). The fresco was painted for the rural church of Santa Maria di Momentana, in Monterchi, Piero’s mother’s village, not far from his own birthplace of Borgo San Sepolcro. The fresco was buried and walled up when the church was destroyed in 1785 and then uncovered in 1889. Giorgio Vasari, whom Hantaï read attentively,89 emphasizes the biographical nature of this painting. Although the facts he mentions have not always been confirmed, they were clearly a valuable source for Hantaï: “Piero was born in Borgo San Sepolcro; . . . he was named after his mother, Della Francesca, because she was pregnant with him when his father, her husband, died, and because she raised him and helped him acquire the high repute his good fortune granted him.”90 Vasari then links Piero della Francesca’s return to Borgo San Sepolcro to his mother’s death. According to Vasari, the fresco of the Madonna del Parto was painted during this period of mourning.91

A parturient Virgin, the Madonna del Parto shows a woman of the people, standing upright, emerging from the half-light of a canopy, wearing a dress with a slit across the belly to signify her pregnancy and the absolute mystery of a virginal conception. This fissure is a fold on the interiority of the creative gesture, as are the folds of repeated motifs of the crimped padding in the canopy, in every way similar to the knotted padding of the Tabulas before unfolding. In this way, the enigmatic Renaissance painting would appear to be an allegory of Hantaï’s own painting, which he claims by invoking its name.

In the photograph of Anna, several undone buttons on the slim-fitting jacket reveal the indigo apron. This opening, in turn, evokes the Madonna del Parto, one of the most original representations, atypical in its insubordinate posture, of the pregnant Virgin, whose Gothic motif, established as early as the thirteenth century, was fading and would be banned by the Council of Trent in 1563 as doctrinally fallacious and indecent.

Hantaï wrote of . . . del Parto. Tabula: “The caput mortuum color enters the canvas instantly. It doesn’t blotch, emphasizes cuts, splinters, and starbursts, dry and unseductive. With the knots removed and unfolded, the padding opens into slits everywhere. A la Madonna del Parto.”92 I note the Latin term caput mortuum, which he uses to describe the nuance of his painting, a term that evokes old chemical practices and means “dead head.” It evokes the as yet unnamed blue waves of Homer, who described the sea as “wine-dark.” It resonates in unison with the universe of voluntary extinction that surrounded Hantaï’s work during the years 1982–92, a time of revisions and examinations, exercises in the manner of Ignatius of Loyola.

Between Giotto’s blue-black and Piero della Francesca’s caput mortuum, the invention and development of folding as method took hold, with the Mariales between 1960 and 1962 constituting their first pictorial act. Hantaï called them Manteaux de la Vierge. This “Mantle of the Virgin” motif was first articulated in the thirteenth century and formalized in religious iconography in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Virgin of Mercy was there to exercise her protective, redeeming virtues against the plagues, wars, and famines ravaging Europe. The open canvas of the pallium, stretched out, lifted up, and blowing in the air, hovers and folds to envelop and shelter the suffering people. This emblematic gesture with a heuristic value was at the heart of Hantaï’s folding procedure. An unfolding of a blank canvas that gathers, closes, and unfolds.

The painter related his first experiences of color to his mother’s powers, associating them with the ancestral skills and techniques of the “ancient world” that he knew: “Thinking about it, these are my memories: I saw colors, because my mother wore colors. . . . my mother had the most incredible dresses: pure color, all color! Purples, greens, pinks, and blues. Unbelievable!”93 Regarding this work made consciously to disappear, the extravagant pomp of dress and finery, and the cult of fleeting beauty that characterized Swabian celebrations and ceremonies dedicated to the Marian cult, Hantaï recalled:

When I was a child, my mother’s skirts and aprons always needed ironing for feast days. So we ironed and dried at the same time, by which I mean that we prepared a kind of roll, moistened [it], made square folds [of the clothing] and started to roll it back and forth for half an hour or an hour. And as the material dried, so the color transformed it into a completely different material, until it became drier and drier and more and more sheeny. . . . The most surprising thing about this is that these were ordinary fabrics. . . . As we ironed, the colors changed and become velvety and bright like the most noble fabrics in the world. My mother always said that if the work was done well you could take the apron and look at yourself in it and see yourself like in a mirror.94

In this way, by positing an equivalence between work and beauty, Hantaï was blurring the boundaries that shore up the distinction between art and craft, uselessness and utility. Spending money for no other purpose than the “sheen” of a poor canvas transformed these domestic protocols into artistic procedures. His mother’s act of ironing with a roller and iron would thus, through an inversion of terms, be seen to assert the uselessness, gratuitousness, and even arbitrariness that are at the source of the work of art in its modern sense. Hantaï concludes: “Everything is an elementary thing transformed by work into a visual wonder.”95

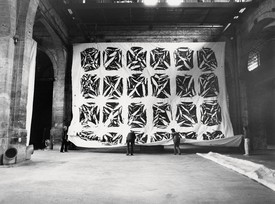

In June 1982 Hantaï made what would be his last trip to Italy. Representing France at the 40th Venice Biennale (June 13–September 12, 1982), he had conceived a group of eighteen monumental Tabulas for the French Pavilion, organized as a polychromatic device responding to one another from room to room. In the end, and despite his disagreement, a group of sculptures was installed in the central space of the pavilion, conditioning and modifying the perception of his installation.96

At the same time Hantaï opened an exhibition in Paris, titled Tabulas lilas (June 17–July 17, 1982), dedicated to a work in progress. To mark his disagreement with the authoritarian intervention in Venice, he subtitled the Parisian show Le deuil de Venise (Mourning for Venice). The exhibition consisted of Tabulas with large squares painted in white on white, the cold white of the acrylic paint contrasting with the warm white of the canvas. The paintings were hung on the walls or placed on the floor, reflecting the brightness of the glass roof overhead and optically covering almost the entire gallery, transforming it into a light box. The minute contrasts between the qualities and luminosities of these warm and cold whites animated their surfaces with optical halos and rings, causing an immaterial lilac color to appear in space. Visitors could experience this ineffable color perception and the sublimity that resulted from the chance interaction between the painted canvases, the site, and the ambient light. The Paris installation was diametrically opposed to the Venice project. For Hantaï, the Tabulas lilas embodied a program involving the extinction of color, whereas in Venice the confrontation of polychrome and monochrome Tabulas in blue, red, green, yellow, and black was intended to break down the chromatic prism.

Following this double pictorial manifesto of polychrome and achromatic paintings, Hantaï decided, in sign of “mourning,” to withdraw from public life and stop exhibiting. He maintained this position for nearly fifteen years. The Tabulas lilas exhibition would thus be the last public presentation of his pictorial work.

On that last trip to Venice, Hantaï visited the Church of Madonna dell’Orto in the sestiere of Cannaregio to see the paintings by Jacopo Robusti, known as Il Tintoretto. While the master executed many works for the church, it was the large, vertical twin panels in atypical format, The Last Judgment (c. 1560), and The Adoration of the Golden Calf (c. 1560), located to the left and right of the apse, that enthralled him.97 He later commented: “[I] saw Tintoretto actively for the first time. Side panels up to the vaults. ‘The extravagant invention of the Last Judgment.’ ‘It looks as if the painter set out to make a mockery.’ ‘Randomly and without design,’ ‘as if to prove that art is but a jest’ (Vasari). One of the most confused and chaotic paintings of the period. Dirty, sloppy, painted with a broom. What a joy! I’ve been seeing it since M.d.2 in this neighborhood. Dedicated to Tintoretto in this place.”98

Giorgio Vasari, one of Tintoretto’s contemporaries, gave an intriguing portrait of the painter in The Lives:

In the same city of Venice . . . there lived, as he still does, a painter called Jacopo Tintoretto, who has delighted in all the arts, and particularly . . . in the matter of painting extravagant, fanciful, swift, resolute, and the most non-conforming mind [terribile cervello] that the art of painting has ever produced, as may be seen from all his works and from the compositions of his fantastic narrative scenes [storie], executed by him in a fashion of his own and contrary to the use of other painters. Indeed, he has surpassed even the limits of extravagance with his new and fanciful inventions and the strange vagaries of his intellect, working with no proper method or draftsmanship, as if to prove that art is but a jest. . . . In the church of Madonna dell’Orto . . . Tintoretto has painted (on canvas and in oils) the two walls of the main chapel, which are twenty-two braccia in height from the vaulting to the cornice at the foot. . . . Opposite to that picture, in the other canvas, is the Universal Judgment of the last day, painted with an extravagant composition [invenzione] that truly has in it something awe-inspiring and terrible, by reason of the diversity of figures of either sex and all ages that are in there. . . . And whoever glances at it for a moment, is struck with astonishment; but, considering it afterwards minutely, it appears as if painted as a jest.99

In homage to Tintoretto’s Last Judgment, Hantaï subtitled his painting Mariale M.d.2 (1962), dating from the end of the Mariales or Manteaux de la Vierge, “Dell’Orto.” The two-tone blue-on-ocher fold-on-fold that forms the allover composition exposes the canvas’s white background, streaked throughout with black spattering. This painting reveals the permanence, rather than the resurgence, of the drip technique that had occupied Hantaï since his discovery of Pollock in Venice in 1948, followed by his abstract pictorial experiments from 1955 onward. In this “sloppy” painting by Tintoretto made “with a broom,” Hantaï identified the Pollockian process of pouring paint along a stick, as well as the one he himself used to scratch and dig into the thick pigment washes of his large-scale gestural paintings. Whether involving a broom, stick, or alarm clock, Hantaï’s means were manifold and their tracings polysemous. On the contact sheets of the photographs taken by Etienne Sved in 1955–56, when Hantaï was painting Sexe Prime. Hommage à Jean-Pierre Brisset (1955), we can follow the stages and traces of these automatic procedures enacted using unlikely impromptu tools chosen in the thick of the action.

Tintoretto’s stubborn engagement took Hantaï back to the jubilant productivity of this period in his work. His declarations notwithstanding, Hantaï did not stop painting when he turned his back on the system but embarked on a sequence that led him to experiment with new ways of painting that combined dripping and folding.

Seeing Tintoretto “actively” inventing ways of extending the format and mechanizing painting at the Madonna dell’Orto rekindled Hantaï’s powerful desire to work. The “joy” he felt at Tintoretto’s deliberate excesses and his irreverence for the rules of painting and the decorum of the milieu enabled him to overcome the disappointments of the Venice Biennale, reinforcing his deep conviction that there was another path for his painting.

Édouard Boubat’s photos of Hantaï’s studio show just how much energy he put into his art at the time. The square, white-painted studio, with its south-facing glass roof, is bathed in extraordinary light. Here the painter asserts his total freedom from the constraints imposed by the system. He painted relentlessly and outside the rules of “productivity” and “fructification” imposed on the mercenary artist in society. Several types of work are superimposed in the studio in successive layers, stapled one on top of the other, dripping with color. The walls are literally covered with a thick mattress of painting upon painting.100 Some of these photos, when reproduced in 1992, publicly refuted the fiction of Hantaï’s disappearance.101

After the asceticism and theoretical dryness of the Tabulas lilas, the paintings of “the last studio” (1982–85) went back to polychromy. They feature unprecedented, composite, shapeless forms, all derived from folding and dripping. Among these forms we find dripping-folding works that take the state of Dell’Orto. Mariale M.d.2 as their starting point and develop its plastic potential. The folds, made in blank canvases, were brushed with several colors and unfolded while the acrylic was still liquid. The paint flowed and squirted from the eye of the fold, causing drips and splashes. Folding took on board Pollockian dripping. The fold drips. The “interminable foldings by successive reductions” took the principle of folding a step further, internalizing the process and turning it back on itself. The painter tore previous paintings in half, folded them, painted them, tore them in half, folded them, painted them, tore them in half, folded them, painted them . . . until he arrived at small-scale paintings with a blurred surface, ballasted by the superimposed of layers of color.

“The last studio” also includes folds executed using multiple folds on folds, preserving the brilliance of the color and the whiteness of the reserve in an unprecedented chromatic balance. With them, Hantaï returned to the art of Cezanne and his abstract watercolors. Here we can observe dichromatic folds in which the white of the canvas is partially covered with a colored juice onto which a dense fold in the complementary color is affixed; irregular polychromatic tabulas left folded, left “in shape,” whose unfolding appears suspended, frozen, and which are crisscrossed by cracks of white; folds combining the principles of the Bourgeons (Buds) and Blancs (Whites), both 1973 to 1974, and many other forms with an operating principle so complex that it becomes uncertain and indescribable. . . . Hantaï was still painting.

1Hantaï was arrested in 1944, fled, took refuge in his hometown of Bia, and traveled to Budapest in early 1945. He participated in the city’s reconstruction and engaged in the cultural and artistic activities of the Academy of Fine Arts, where he had been a student since 1941.

2Szinház, July 24–30, 1946, p. 20. The magazine published a portrait and statement each by Simon Hantaï, Zsuzsa Bíró, and their friend Sándor Zugor, all three recent graduates of the Budapest Academy of Fine Arts.

3Oswald Spengler’s Der Untergang des Abendlandes: Umrisse einer Morphologie der Weltgeschichte was published in two volumes (Vienna: Braumüller, 1918; Munich: Beck, 1922).

4On Virgil’s myth of the Golden Age, see The Eclogues and The Georgics, trans. C. Day Lewis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

5Sandro Botticelli, Spring, c. 1480, tempera on wood, 79 ⅞ × 123 ⅝ inches (203 × 314 cm), Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

6Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Golden Age, c. 1530, oil on wood, 28 ¾ × 41 ⅜ inches (73 × 105 cm), Alte Pinakothek, Munich; Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, 1531, oil on wood, 20 ⅛ × 14 inches (51 × 35.4 cm), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

7“Cézanne wished he could recover a direct vision with nature. ‘Pissarro,’ he used to say, ‘said that we should burn down the Louvre. He was right, but we can’t do it!’” Maurice Denis, “Excerpt from the Journal (1906),” in Conversations with Cézanne, ed. Michael Doran, trans. Julie Lawrence Cochran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), p. 90.

8Presumably this trip was part of an official exchange program, since the students were received at the Palazzo Venezia, the seat of the Italian government, and saw Mussolini there. Exchanges with other Axis countries were encouraged in Italy through the youth enlistment policies pursued by Fascist organizations such as Opera Nazionale Balilla. Mussolini made plans for a spectacular celebration in 1942 to mark the anniversary of the 1922 “March on Rome,” which resulted in his seizure of power.

9Between 1932 and 1940 Hantaï studied at the Ferenc Toldy Technical High School in Budapest. He started taking sculpture classes in the first year of secondary school. He passed the entrance examination for the Academy of Fine Arts in 1941.

10This biographical fact is published for the first time.

11Unless otherwise noted, all quotations from Zsuzsa Hantaï in this essay are taken from a recorded interview with Daniel Hantaï and Jean Haury in May 2023 and from her conversations with the author between May and September 2023. Most of this information has never been published. It provides valuable insights into Simon Hantaï’s life for the period 1946–49.

12Anne Baldassari, “This fold will lose its frown,” trans. Charles Penwarden, in Simon Hantaï: The Centenary Exhibition, ed. Anne Baldassari (Paris: Fondation Louis Vuitton and Gallimard, 2022), p. 62; this catalogue was published in English and French versions.

13Simon Hantaï and Jean-Luc Nancy, Jamais le mot «créateur». . . : Correspondance 2000–2008 (Paris: Galilée and Archives Simon Hantaï, 2013), p. 162.

14Hantaï and Nancy, Jamais le mot «créateur», p. 163.

15Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Artists (1550), was the first to comment on the innovations introduced by Giotto (c. 1266–1337): “Suffice it to say that from this work Giotto acquired great fame for the excellence of his figures and for the order, proportion, liveliness, and ease he naturally possessed, qualities he had greatly improved through study and knew how to exhibit clearly in all his works. For besides the natural talents Giotto possessed, he was very studious and always went about thinking up something new and drawing upon Nature, and he therefore deserved to be called a disciple of Nature rather than of other masters.” Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, trans. Julia Conway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), pp. 15, 17–18, 19.

16“And as far as good style in painting is concerned, we are primarily indebted to Masaccio, for it was Masaccio who . . . realized that painting is nothing other than the art of imitating all the living things of Nature with their simple colours and design just as Nature produced them.” Vasari, Lives of the Artists, pp. 101–02.

17Anne Baldassari, Picasso Photographe: 1900–1916 (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1994); Anne Baldassari, Picasso and Photography: The Dark Mirror, trans. Deke Dusinberre (Paris: Flammarion; Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1997).

18Joris-Karl Huysmans, writing in 1883, criticized the 1880 Salon des Indépendants for Caillebotte’s “indigomania” or “awful blue sin”: “I don’t want to name names here, suffice to say that the majority of them saw through the eyes of a monomania; while one would see intense blue in all of nature and turn a river into a washerwoman’s bucket of Reckitt’s blue; another would see purple—landscapes, skies, water, flesh, everything in his work would be tinged with lilac and aubergine; ultimately, most of them would have confirmed Dr Charcot’s experiments on the deteriorations of colour perception, which he’d observed in many hysterics at the Salpêtrière hospital and in numerous people afflicted by diseases of the nervous system. Their retinas were sick.” Joris-Karl Huysmans, “Exhibition of the Independents in 1880,” in Modern Art (L’Art moderne), trans. Brendan King (Sawtry, UK: Dedalus, 2019), pp. 102, 105.

19Leo Steinberg develops the concept of “elasticity” in “The Philosophical Brothel,” originally published in two parts; see Art News 71, no. 5 (September 1972), pp. 22–29, and Art News 71, no. 6 (October 1972), pp. 38–47. An expanded version appeared in October 44 (Spring 1988), pp. 7–74. Picasso refers to “paperistic” procedures in a letter to Georges Braque dated October 9, 1912. See Judith Cousins, “Documentary Chronology,” in Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism, ed. William Rubin (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1989), p. 407.

20Another possible indirect source for Hantaï’s painting is Caravaggio’s The Taking of Christ (1602), a copy of which is in the Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest.

21Pablo Picasso, The Old Guitarist (The Blind Guitarist), 1903–04, oil on canvas, 48 ⅜ × 32 ½ inches (122.9 × 82.6 cm), Art Institute of Chicago, Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection.

22Hantaï quotes Saint Augustine’s Confessions, book 10: “I resist the allurements of the eye for fear that as I walk upon your path, my feet may be caught in a trap” (trans. R. S. Pine-Coffin [Paris: Debécourt; London: Penguin, 1961], p. 240).

23Henri Matisse, Le Bonheur de vivre, 1905–06, oil on canvas, 69 ½ × 94 ¾ inches (176.5 × 240.7 cm), Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia.

24Hantaï took part in the activities of the Cercle Culturel de l’École Européenne, founded in March 1945. Between September 1945 and May 1946, he attended art history classes given by François Gachot, director of the French Cultural Institute. They struck up a close friendship. Gachot introduced him to the works of Matisse and Bonnard, gave him access to his personal library, and taught him the rudiments of French.

25Antoine Watteau, Pierrot (formerly Gilles), c. 1718, oil on canvas, 72 ⅝ × 58 ⅞ inches (184.5 × 149.5 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris.

26Paul Cezanne, Mardi Gras, 1888, oil on canvas, 40 ⅛ × 31 ⅞ inches (102 × 81 cm), Pushkin Museum, Moscow.

27Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Boy as Pierrot, c. 1785, oil on canvas, 23 ½ × 19 ⅝ inches (59.8 × 49.7 cm), Wallace Collection, London.

28A second Self-Portrait with a Red Star, dating from 1946‒47, before his departure from Hungary, displays the same characteristics. This work is known only from a single black-and-white photograph.

29In his treatise Libro dell’arte, written between 1390 and 1437, the Tuscan painter Cennino Cennini brings together all the painting techniques (tempera, fresco, oil, miniature) used in the artists’ studios of his time. He describes verdaccio as a preparation composed of one part black, two parts ochre [yellow], resulting in a light grayish green, close to green earth, used as an undercoat for frescoes. This neutral tone helped define the values of the figure. By extension, this technique was applied to tempera and then to oil painting by the Italian and later Flemish primitives. This colored background or greenish imprimeure enabled a more subtle and realistic treatment of skin tones, enhancing the warm colors painted over it.

30Sent to the artist in 1998 and annotated in 2001, the photograph is now in the Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris.

31The Archives Simon Hantaï is working to establish a catalogue raisonné of the artist’s works.

32Zsuzsa Hantaï as quoted in Anne Baldassari, “He lived in his painting: Interview with Zsuzsa Hantaï,” trans. Charles Penwarden, in Baldassari, Centenary Exhibition, p. 24.

33Simon Hantaï speaking in Simon Hantaï ou les silences rétiniens, a film by Jean-Michel Meurice, 1976, 58 min.See also Hantaï and Nancy, Jamais le mot «créateur», p. 69: “M. Babits (an important Hungarian poet) translated The Divine Comedy, which we had read just after the war. Zs. learned Italian so she could read it.”

34Simon Hantaï, “Notes manuscrites,” undated manuscript given to the author in 1991.

35The “Free Territory of Trieste” was a neutral state until the Treaty of Osimo of October 10, 1975.

36The omitted passage reads: “go to get money sent by my family, the Kelens, who had emigrated to Montreal (the Kelens had changed their surname from Klein to Kelen, the name of my mother, Cornelia Klein, so as not to suffer the anti-Semitism they were fleeing in Hungary). They had contracted a family debt with my father before their departure in 1929, just before the stock market crash.”

37Antal Bíró (1907–1990) traveled around Europe before settling in Paris in 1928. He studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière from 1932. Returning to Hungary in 1939, he enrolled at the Budapest Academy of Fine Arts. In 1944–45 he was part of an artists’ colony with Judit Reigl, Zugor Sándor, and Lipot Böhm. He was in Rome on a scholarship in 1946–48, at the invitation of Tibor Kardos. He traveled to Sweden, then rejoined his fellow Fine Arts students Simon and Zsuzsa Hantaï in Paris in 1948.

38Lipót Böhm (1916–1995), whose pseudonym was Poldi, took part in the group of artists who won scholarships and stayed in Rome in 1946–48. He later immigrated to Paris.

39Judit Reigl (1923–2020) was born in Kapuvár, Hungary. She studied painting at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest, in the atelier of István Szőnyi. Together with Zugor Sándor and Lipót Böhm, she took part in an artists’ colony in 1944–45. She received a scholarship from the Hungarian Academy in Rome and traveled in Italy from 1946 to 1948. In October 1948 she returned to Hungary. Determined to leave the country, Reigl succeeded in March 1950 after seven unsuccessful attempts. She reached Paris a few months later. Her first works in Paris were influenced by Surrealism. From 1952 onward, Reigl began experimenting with gestural painting and became interested in automatic writing. In May 1954 her friend Simon Hantaï brought André Breton to her studio; Breton immediately offered her a solo exhibition. After initially declining, she accepted in November. The exhibition was held at À l’Étoile scellée gallery, following Hantaï’s show there in January.