Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014, and is currently the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly.

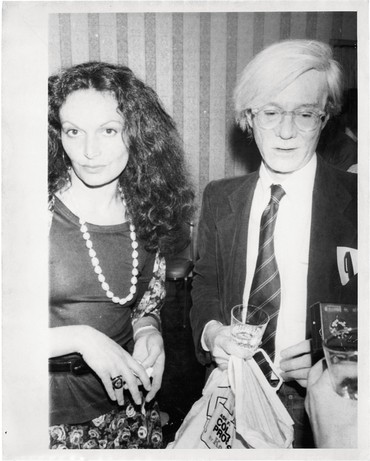

Derek BlasbergIn every issue of the Quarterly we have a conversation with a fashion professional and ask about the influence of art in their creative process. In September, at Gagosian’s Paris gallery, we’re opening an exhibition of Andy Warhol’s personal photographs and Polaroids, one of which is a fabulous image of you, so I thought this would be the perfect time to talk to you. Do you remember being photographed by Warhol?

Diane von FurstenbergHe photographed me a few times, actually. When I arrived in New York, in the late 1960s, Andy Warhol was part of the scenery. He was like a piece of furniture: he was everywhere, and I was everywhere too. I saw him all the time! He was a voyeur. He let you speak and he didn’t speak very much and when he did it was always something short and he would say it to make you say more. He wanted to know everything about you, he wanted to take your picture, he had a recorder in his pocket, he wanted to paint you. He was all-absorbing. But looking back, he had such an incredible sense of branding. He had a vision of what the world was going to be that none of us realized until it was here. In a way, he did social media before social media. He would have gone insane with Instagram! He was the original influencer.

DBPopular culture is obsessed with Warhol, more so now than when he died. This year, one of his Marilyn Monroe portraits sold for $195 million. Are you surprised by this legacy?

DVFTo tell you the truth, I was surprised it took so long for people to understand how important he was and how cleverly he captured the contemporary moment. When he died, he was a famous artist, but he wasn’t as respected in that moment as some of the other artists of his generation. Of course that’s changed now.

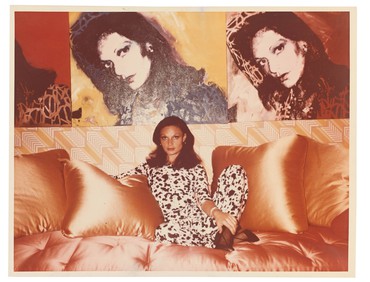

DBIn addition to the Polaroids, he also did two series of his iconic silk-screen portraits of you. Do you remember those?

DVFThose too started with Polaroids. Polaroids were a big part of his process—when he was doing portraits of living people, that’s how his work would begin. His first series of portraits of me, which are the ones where it looks like I’m reclining and my arms are folded over my head, he did in the 1970s. The Polaroids that were the basis [of that series] were taken at my house in the city. It was midnight and he was at my apartment and he’d been saying, I want to do your portrait, I want to do your portrait. So I said OK, let’s do it right now. He needed a white wall to shoot me in front of but I was living on Park Avenue at the time and the apartment was very decorated. Every wall had a print or upholstery or something colorful on it. But in the kitchen there was a small wall that was white. It was between two doors, very narrow, which is why my arm is up and folded over my head like that.

For the second series [of his portraits of me], which he did in the ’80s, I actually went to the Factory to have the Polaroids taken. He had an idea for an exhibition, which by the way never happened, that he titled Beauties, and he asked many women to be a part of it, including me, Liza [Minnelli], Bianca [Jagger], Carolina [Herrera], and some other women. You’ve probably seen the paintings of those women from that series—he asked us all to wear kabuki-style makeup, so in the Polaroids you see all these women with white stuff on their face. It was probably easier for him to transpose the image onto the silkscreen that way.

DBI believe you own all of those portraits now, right?

DVFI have nine in total, four from the ’70s series and five from the ’80s series.

DBDid you like them when they were done?

DVFThe first series I really liked. I remember that I bought two from him and he gave me the third one. I actually didn’t like the second series at the time, but he gave me one, which I put in storage, and I didn’t buy any. In time, though, and after he died, I grew to like them and when they became available I bought them back. I have a few in my design studio in the Meatpacking District in New York and some at my house in Connecticut.

DBI love them. And I love your sitting room, where several of the ’80s versions are hung high on a wall, which look incredible.

DVFI like to live with them because when I see them they remind me of a wonderful time in my life.

DBLet’s go back to the beginning. When you were young, did art play a big part in your life?

DVFI was born in Brussels, which means that as a child, I was exposed to such extraordinary art. And I don’t mean contemporary art, I mean true masters of painting. I remember the first time I went to a museum as a child and was surrounded by the icons of the Flemish school, which flourished from the Late Gothic through the Renaissance and to the Baroque. Rubens! Then, of course, the art in that part of the world became more modern and surrealist. [René] Magritte! Of course, when you’re young, you’re unaware of how special what you’re surrounded by is, but looking back at those painters, I can say now that they played a huge role in shaping my appreciation for beauty.

DBAnd then you moved to America, which doesn’t have a historical-art context like that. Was that a shock?

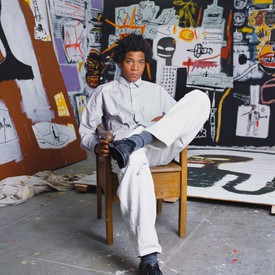

DVFWhen I arrived in New York, it was all about contemporary art. We had [Robert] Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, [Jasper] Johns, Warhol: all of them were everywhere and it felt like a thing, and I remember loving how you felt like they were really responding to a moment. Also, you’d see these artists out in the city. They were around. But it wasn’t just the artists we found inspiring, it was the whole contemporary-art gallery scene. For example, this is when I first met Leo Castelli, and all of these other people who were doing new, interesting things, like Happenings in the basement of the Guggenheim [Museum]. We would go to art things all the time, much more than I think young people do now. It felt like art was very present in New York in the 1970s. In fact, I would go as far to say that the three most present things in New York at that time were art, the liberation of women, and, because this was after the invention of birth control but before the AIDS epidemic, sex.

DBWhat a time to be alive!

DVFIt was! New York in the ’70s was about reinventing freedom. We really thought we were doing that. We expressed it in many ways and the convergence of the fashion and art worlds was a huge part of that. The fashion people who inspired me at the time did an incredible job of capturing that part of the zeitgeist. I’m talking about Halston, most obviously, but also Stephen Burrows and Giorgio di Sant’Angelo, and so many incredible fashion people who were inspired not only by art but by all the culture they were exposed to. I first met Diana Vreeland in 1972, and she was an intimidating woman but incredibly inspired. She saw things in people before they saw it in themselves. She was one of the people who gave me confidence with my brand.

DBHow does the world of art inspire you today?

DVFEvery day! For me, art is about emotion. A great artist manages to capture true emotion, whether it’s despair or ecstasy or loss or hope. On the other hand, design has a utilitarian purpose. It’s very different. Fashion is a reflection of the times, and when it’s good, it serves a purpose beyond being decorative. In 2017, the Museum of Modern Art organized an exhibition of the 111 items that represented fashion’s most significant contributions to culture from the last 100 years. It included items like the bikini, the hijab, the fanny pack, Yves Saint Laurent’s safari suit, the kilt, the sari—and my wrap dress. It also included the surgical mask, which came back in fashion in a very utilitarian way during COVID.

DBIn 1976, the wrap dress landed you the cover of Newsweek magazine, didn’t it?

DVFYes!

DBCan designers be artists?

DVFYes, of course. And it can blend. If you do ceramics, you can be both utilitarian and inspired.

DBWhat inspires you now?

DVFWhoever created nature is the biggest artist in the universe because that manages to be both utilitarian and inspiring. That’s why, if you asked me who the biggest artist and designer of all time is, I would tell you Leonardo da Vinci. The single greatest inventor of all time. That’s because the thing he was the most proud of was that he could read nature. He realized that the purest, most beautiful, and most utilitarian state of art was found naturally in nature and in the human form. He was a genius.

DBWhat’s your current relationship with art?

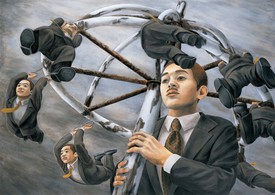

DVFI’ve never been one of those greedy collectors who buys a bunch of things and puts them in storage. The first painting I ever bought was a Pre-Raphaelite painting that I bought in a jewelry store. At the time, I figured I was making money from women so I should celebrate their beauty, especially in the art of Pre-Raphaelite painting. Soon after, I began acquiring art from my peers and my friends, including folks like Francesco Clemente, Barbara Kruger, and Anh Duong. More recently I found some Chinese artists that I admired and commissioned a few things from them. I’m also a fan of Damien Hirst—we acquired one of the paintings from his last Beverly Hills show, it’s at our house in California. I have to give him a lot of credit because he obviously captures the moment so well and I think it’s important to support artists of your time. And something else I believe in: I don’t use art for profit. I have a funny story: once when I was in China, someone asked another person what kind of art they collected, and the person responded, I collect Gagosian art. I thought that was great and of course the person I called and told the story to was Larry. But I like to see and be inspired by my art, and that’s the purpose it serves me.

DBI think you’re going to be the subject of your own exhibition, is that true?

DVFThere have been a few exhibitions about my dresses. You came to my opening in Moscow in 2009!

DBYes, of course! That exhibition was great. I remember all of the Warhols were there too. I also remember that we went to a nightclub and they had people on horseback!

DVFMy next show won’t be in Russia but I’m excited to tell you that next year there’ll be a show in my hometown, Brussels, curated by Nicolas Lor, at the Musée Mode et Dentelle. He actually spent the last five days in the archives of my house in Connecticut going through my diaries.

DBI’ve always admired how you keep a diary. It’s a wonderful practice.

DVFI brought Nicolas down there the other day to show him where the diaries were. I picked one of them up at random and I opened it up and landed on my entry from September 11, 2001. I had written about how it started as such a beautiful morning and I was reading the newspapers. I had had a fashion show two days before and the reviews were coming out. Then my son called to tell me to turn on the news, and we both just watched in horror as the rest of the day unfolded. I wrote how my son had told me that this was the first brick in the wall of capitalism being removed. Do you keep a diary?

DBI try to, but I rarely write in it. Who has the time?

DVFWhen you write in it, are you honest?

DBI think so. Isn’t that the point?

DVFYes, it is. And I’m happy to hear that. I have to say the one best piece of advice I could ever give someone is to keep a diary. A diary is a written record of the relationship you keep with yourself, and that is the single most important relationship you will have in your entire life.