Emma Cline is the author of The Girls (2016) and of the story collection Daddy (2020). Cline was the winner of the Plimpton Prize and was named one of Granta’s Best Young American Novelists. The Girls was an international bestseller and was a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award, the First Novel Prize, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize.

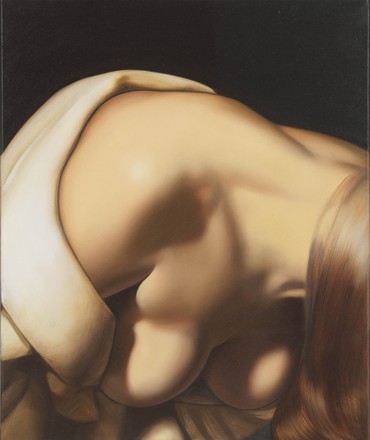

The paintings of Anna Weyant evoke a certain airless time of day: 5pm, the house still, the air going stale, the silver starting to cast off reflections from the lights. Composure with tension building underneath, an edge, like someone clearing their throat in a silent room. There is the quality of waiting, as in the opening scenes of a fairy tale—a girl, in prim clothes, about to be acted on by forces beyond her understanding, the normal rules of the universe tinted with a dream logic.

I was sitting at a long table with a lot of nice things on it, begins a short story by Alexandra Kleeman called “Fairy Tale.”

My mother and father were sitting next to each other on the long side of the table, and a man I didn’t recognize at all was sitting next to them. I sat across on the other end, alone.

I was looking at all of the things and trying to notice connections between them. Why this table, why now? . . .

It was then that I noticed none of the others seated at the table were looking at the table or its contents. They were all looking at me. . . .

You were announcing your engagement, said my father helpfully.

To who? I asked. . . .

To us, they said. All of you? I said.

No, only me, said the man in the button-up shirt, whom I did not recognize. . . .

Who am I engaged to? I asked.

To me, he said, no longer looking satisfied.

The young woman finds herself playing a part in a story that has lost all connection to reality. In this world that she doesn’t recognize, her fate is out of her hands. Even her mother and father are no help—they are part of the confusion, no longer reliable. What surreal logic propels her forward?

I think of Anna Weyant as a great teller of fairy tales. And girlhood is a kind of fairy tale, one in which your existence, even your body, can become distorted and unreal in sudden and even violent ways. As in a fairy tale, women are often subject to forces beyond their control: the strange dance of passivity and power that they experience, cast in the starring role of the story while simultaneously defanged, made into dollhouse dwellers, figures arranged in the scene by hands outside the frame. And, as in the great gothic fairy tales, there is, in Weyant’s paintings, a sinister elegance: the Dutch-master black of her backgrounds, the expertly rendered silver candlesticks and unbelievably lovely roses, the salmon-pink balloons and the figures done in narcotic marzipan smoothness. But Weyant’s universe never stops at that polished surface—the work is deeper than that, much deeper and much darker and very, very funny. There is always another element cutting through the static, an added bite—a fearless mordancy and a bracing wit that feel entirely contemporary and entirely her own.

In Weyant’s telling, the valence of the fairy tale takes on a savage and brilliant edge: the tropes are distorted, slyly rearranged, made more uncanny or hilariously deflated. A young woman flops out of a many-tiered birthday cake, her hair a flag of bored surrender. A gleaming revolver is now beribboned, a weapon made into a lovely little gift or even a kind of acerbic invitation. A pair of wine glasses meet in a crashing “Cheers,” both glasses shattered into jagged teeth—social encounters as minor-key battle. A woman engages in what at first seems to be convivial conversation; then her smile becomes more of a grimace, a jackal’s bark. Her hand, bound in gauze, rests politely on the table, an injury that you suspect will go unexplained.

There was a book of Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales that fascinated me as a child. I still have the copy I grew up reading—a clothbound Junior Library edition with jewel-toned illustrations by Arthur Szyk. Even though I read them obsessively, the stories gave me a queasy feeling. They were frightening in a way that I couldn’t yet understand, and the horror was doubled by the illustrations, baroque images of girls and women in trouble. One illustration obsessed me more than the others, accompanying the story “A Girl Who Trod on a Loaf.” It’s a weird little tale in which a girl’s vanity (protecting her new shoes from the mud at the expense of a loaf of bread meant for a hungry family) results in her doom (instantly banished to a terrible underworld). The illustration in my book shows a blonde, droopy-eyed Szyk girl in a red fur-trimmed coat, trapped in a massive spider’s web, surrounded by all manner of creatures who mean to do her harm—gape-mouthed dragons and fearsome bats and an enormous rocky toad. “Great, fat, sprawling spiders spun webs of a thousand years round and round their feet,” the caption reads. A thousand years! Doom! Yet the girl’s expression is only mildly concerned. There’s something in the way her eyebrows are raised, a weary resignation in her features, that seems almost to say, Ok, great, fat spiders, hideous beasts, a thousand years—so what?

The women in Weyant’s paintings navigate their uneasy surroundings with that same cool knowingness, a gimlet-eyed awareness that inures them to the vagaries of this fairy-tale world. These are not the passive heroines of fairy tales, asleep for 100 years—if a Weyant subject slept for 100 years, it would be because she was bored, withdrawing from society in Bartleby-like protest: I would prefer not to.

If the subjects at first appear strangely calm, even under duress, on second glance their remove starts to look like a choice, an exhausted opting-out or a calculated pose, a weaponized strategy formed as an illogical response to a ridiculous world. These strategies can result in their own form of violence, too: a young woman with a bow around her ponytail, taking the innocent, enthusiastic pose of a cheerleader, is—you realize—standing on brutal tiptoe, her body balanced on a young woman’s cheek. Do both of these women have the same face? The brutality is turned inward, acted out on another version of the self. As in a horror story, the call is coming from inside the house. Or from inside yourself. Even so, the expressions on these faces are placid, amused. The woman grins happily as her cheek is ground down by the cheerleader. None of this, their faces seem to say, is entirely unexpected. Even when a Weyant subject is screaming, the scream seems hilariously mellow, self-aware, an echo of an echo of terror.

In Weyant’s recent paintings, these ripples of otherworldliness and the uncanny appear in more overt ways, breaching their formerly polite bounds. It’s exciting to see these parts of her work intensify, torquing her visual universe with new energy. Weyant’s bone-white roses, unsettlingly perfect, are now joined by flat fake daisies, like the gag flowers on a clown’s lapel that might suddenly blast you with water. The elements of artifice are foregrounded, made visible. In another painting, a cartoon face distorts the features of a beautiful young woman, like a startling rude blurt into this composed world. Something hidden makes itself known. So much is controlled; then Weyant ruptures the control with psychological precision, exposing what spills out of us even when we try to keep the boundaries maintained.

In a still life of polished silver, the reflections in the surface of the pots and pans aren’t just innocuous flashes of light and dark—we see a shadowy, sinister figure creeping in the background, a knife raised in their hand in Norman Bates fashion. The polish reveals the poison. But is the danger real? Or is the violence cartoonish, just juvenile haunted-house antics?

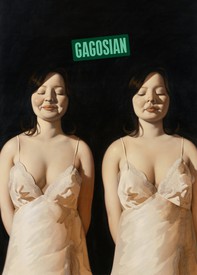

Weyant plays with doubling: a woman in a silk slip dress smiles in a satisfied, internal way, her eyes closed. Then she is twinned, only the twinned version glances down to the side with mild disdain or regret, like that moment of pause after you’ve said too much at a party. In a single painting, Weyant toggles between these two selves, the pleased self and the self that polices that pleasure, doesn’t appear to quite trust it.

There’s something very funny, too, about the discomfort in an Anna Weyant painting. It’s a pressurized, antic hilarity, the tension between the lovely, prim surface and what’s underneath, threatening to breach that surface—like the queasy and awful thrill of trying not to laugh at an inappropriate time. Needing to laugh, but knowing you absolutely cannot laugh—humor teetering on the knife’s edge of horror, like the balance Weyant so expertly strikes. A thousand years bound in a spider’s web, a woman en pointe on your cheek, a figure with a knife creeping up behind you: horrifying? Maybe. Maybe also kind of funny. And maybe that mediation between humor and horror is a truer kind of fairy tale, a fairy tale that crystallizes this moment brilliantly, as only Anna Weyant can.

Anna Weyant: Baby, It Ain’t Over Till It’s Over, Gagosian, 980 Madison Avenue, New York, November 3–December 23, 2022

Artwork © Anna Weyant