John Elderfield is chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and was formerly the inaugural Allen R. Adler, Class of 1967, Distinguished Curator and Lecturer at the Princeton University Art Museum. He joined Gagosian in 2012 as a senior curator for special exhibitions.

Before Chardin and Cézanne tipped the scales, still life painting was widely understood to be inferior to figure painting. The critical discussion of Anna Weyant’s recent Gagosian exhibition revives that old understanding, having far less to say about the still lifes than about the figures—reasonably so, I suppose, because the figure paintings are larger, more dramatic, and speak more explicitly to an awareness of popular culture. Nonetheless, there is good reason to pay attention to the still lifes: they especially reveal the stylistic sources of Weyant’s work in what the great nineteenth-century critic John Ruskin called works of “imitation,” namely, smoothly painted, highly illusionistic canvases of volumetric forms where “the eye says a thing is round, and the finger says it is flat.”1

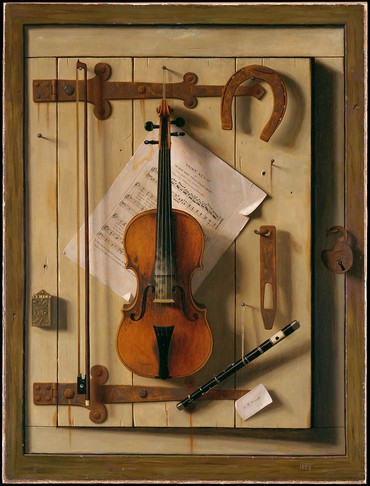

The seventeenth century was particularly rich in such works of imitation. Among them were trompe l’oeil paintings specifically designed to deceive the eye into mistaking artistic fiction for objective fact, a device that became especially popular in nineteenth-century America.2 And by a fascinating coincidence, Weyant’s exhibition was on view in New York when the city’s Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its exhibition Cubism and the Trompe l’Oeil Tradition, which juxtaposed such historical works with examples of Cubist compositions from early in the twentieth century.3 I shall come to the latter exhibition presently, but first want to say something about Weyant’s still lifes and their relationship to her figure paintings.

The Uncanniness of the Ordinary

A recent interview with Weyant was titled “Welcome to the Dollhouse,” and the association of the young women she has painted with dolls is so prominent in her art that it has gained a great deal of attention.4 Little mentioned is the dollhouse itself. Writing on the subject of the miniature versus the gigantic, the literary critic Susan Stewart has written of dollhouses as “the most consummate of miniatures,” representing in small scale the “articulation of the tension between inner and outer spheres, of exteriority and interiority,” in houses for human habitation.5 An artist’s studio may be said to do the same, especially since it is the principal place where the exterior world gets transformed into the interior world of works of art. And, if the studio contains a doll to paint from—if the studio becomes a kind of dollhouse—the relationship of exteriority and interiority is matched by that of the animate and the inanimate.

In a different but analogous way, that animate/inanimate relationship is also invoked by still lifes painted in artists’ studios. If the setup for such a work comprises perishable items, it will sooner or later earn the French name for a still life, nature morte (dead nature). As Stewart has observed, “the world of objects is always a kind of ‘dead among us.’” Among objects, she adds, a doll “ensures the continuation, in miniature, of the world of life ‘on the other side.’”6 But more broadly, as another critic, Michael Riffaterre, writes, “Any statement of motionlessness will generate a statement of motion. The more natural and permanent the movelessness, the more striking the mobilization, and the more suggestive of fantasy.”7

As these and many other writers have explained, this works in two ways. Put simply, the theme of the still life is arrested life—the idea or feeling that nothing changes, that the instant will remain as it is described, that this particular configuration of consumer or consumable objects will define the values of the artist. At the same time, objects brought into the studio, often to join those kept inside, will speak of their sources and their associations outside of the studio, and hence of themes, dreams, even secrets, of which the artist may or may not be conscious. In this dual aspect, the still life joins the contrasting modes of exteriority and interiority to a contrast of the inanimate and an imagined animation. The art historian Meyer Schapiro’s 1968 essay “The Apples of Cézanne: An Essay on the Meaning of Still-Life” is a classic study of how inanimate objects can open onto a mobile world of fantasy.8 As Michel Foucault had put it a few years earlier, “That the world of things can open itself to reveal a secret life—indeed, to reveal a set of actions and hence a narrativity and history outside the given field of perception—is a constant daydream that the miniature presents.”9 Or nightmare, perhaps. Weyant’s painting of a lily juxtaposed with a revolver bound in a gold ribbon does seem funereal.

An essay, at once dense and beautiful, by the philosopher Stanley Cavell, “The Uncanniness of the Ordinary,” speaks of “the ordinariness of human life, and human life’s avoidance of the ordinary”—but not by seeking the extraordinary: “The aspects of things that are most important for us,” Cavell quotes from Ludwig Wittgenstein, “are hidden because of their simplicity and [ordinariness, everydayness].” Some of these aspects are missed because they are obvious. Nonetheless, “the angel of the odd” floats over the ordinary, and may reveal, when noticed, what Cavell calls “the surrealism of the habitual.”10 Those of Weyant’s still lifes that do not juxtapose objects to shape a strongly narrative message, as the lily-and-revolver painting does, but simply offer ordinary objects—whether solely or with understated, or unstated, associations—may be said to engage that form of surrealism. But a slippery slope leads from these paintings to those that defamiliarize objects momentarily by showing them inverted or from other unexpected views, or in incomprehensible or provocative close-ups that engage the surrealism of the unordinary. This is more familiar to us from Surrealism itself, with the advantages and disadvantages that familiarity affords.11

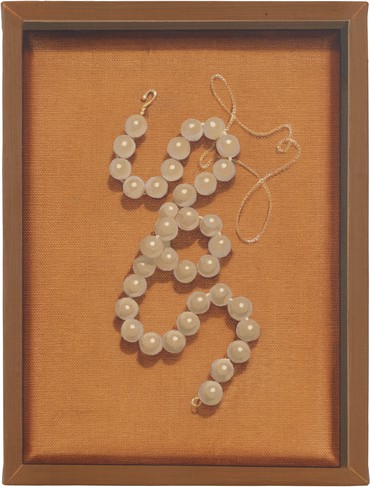

It may not be thought unexpected that Weyant has ventured into the genre of trompe l’oeil painting, depicting objects as if pinned in place on a canvas or panel—or, perhaps, lying as if in a tray. “Trompe l’oeil,” one thoughtful critic, M. L. d’Otrange Mastai, has observed, “is not merely a certain kind of still life painting; it should in fact ‘out-still’ the stillest of still lifes. Ideally, it should be posed, immovable, with no turbulence and no excess of any kind.”12 However, when the eye is fooled into thinking that a represented object in such a painting is the thing itself, that object will, in fact, seem potentially movable. The pleasure comes when the viewer recognizes that it is a representation, and therefore eternally immovable—the surprise of a picture changing identity, as anthropomorphic landscapes do, such as those of the sixteenth-century painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Also, this kind of play turns uncertainty into a game. In Ruskin’s discussion of “imitation,” he observed that “gentle surprise . . . can be excited in no more distinct manner than by the evidence that a thing is not what it appears to be.”13

Trompe l’Oeil

Writing in Artforum on the Met’s exhibition Cubism and the Trompe l’Oeil Tradition, art historian David Joselit complained of its curators’ justification for placing Cubism in the context of that tradition: “A self-referential art that calls attention to its own artifice, trompe l’oeil, like Cubism, involves the viewer in perceptual and psychological games that complicate definitions of reality and artifice.”14 Joselit objected to this claim of likeness, arguing that while the self-referentiality of Cubism lies in its combination of different, contradictory visual languages in a single work of art, continuing to perplex us, that of trompe l’oeil lies in its use of a single, highly mimetic language to represent what may fool us—but just for a moment—to think it is not a work of art but something real.

So far, so good. However, the use of trompe l’oeil details within Cubist paintings associates them with famous early instances of trompe l’oeil. Looking at a picture representing a bee on a painted flower, the Greek philosopher Philostratos raised the question: has a real bee been fooled by a painted flower, or have we spectators taken a painted bee for a real one? Legend has it that a painting of grapes by Zeuxis did attract birds, and that a painting by Giotto included a fly that viewers would try to swat away. Similarly, an abstracted still life by Georges Braque famously contains an illusionistic nail; there are both painted and actual wooden veneers in his and Pablo Picasso’s paintings, and so on. These clearly form exceptions to Joselit’s claim that “if the viewer of a trompe l’oeil painting enjoys being at once deceived and not deceived, the spectator of Cubist paintings must suffer the discomfort of not knowing and not mastering what is on view.”15 It might have been better to say that the spectator of Cubist paintings is offered both the enjoyment and the discomfort.

Joselit associates the discomfort with the wider modernist project, making it the product of “one of the foundational tendencies of modernism” and part of “modern art’s enduring disruptive tendency.”16 At this point we may reasonably ask: has this tendency endured because we find it comforting to be discomforted? Weyant’s still lifes are, of course, very far from Cubist ones; but those that do not adopt a trompe l’oeil format—the majority of them—also offer the spectator discomfort as well as enjoyment. “The angel of the odd” floats over them. Joselit concludes his discussion of the Met’s exhibition with the suggestion that one reason why the curators take trompe l’oeil as a historical forebear may be that “in 2022 we are mired in toxic politics of trompe l’oeil . . . taking pleasure in being deceived while knowing better all along.”17 While we do not know how many of the politically deceived know better, we do know that technological deception is widely embraced. Weyant’s paintings allude to it by ironically adopting the look of glossy, expensive-product advertising—ironically, because that smooth high-gloss finish also associates them with the highly mimetic art of the past, including trompe l’oeil painting. Moreover, an art of imitation is the best vehicle for deception, and therefore for duplicitous seduction.

Volumetric Projections and Happy Places

In 2018, art historian Anna Daly published a fascinating account of how Clement Greenberg’s opposition of “kitsch”—illustrational art designed to appeal to undiscriminating taste—to “avant-garde” art prompted discussions that bear more than a passing resemblance to the critical reception of trompe l’oeil painting in the nineteenth century. Owing to this association, she argued, highly illusionistic works came to be disdained as not the kind of thing that serious modernist artists produced.18

Greenberg had written in 1939, “Self-evidently, all kitsch is academic; and conversely, all that’s academic is kitsch.”19 He did not say what “academic” meant, but we must assume that he was thinking of the collapse of great illusionistic painting in France in the mid-nineteenth century into the pallid art of the Salons, and of its replacement by the materialist art of Gustave Courbet and the avant-garde artists who followed him. Such artists, he claimed, “derive their chief inspiration from the medium they work in.” Therefore, “avant-garde culture is the imitation of imitating”; that is to say, is built on the material processes of preceding works of art, and therefore requires effort and experience from its audience. In contrast, the kitsch artist, like the exhibitor in the Salons, “can paint so realistically that identifications are self-evident immediately and without any effort on the part of the spectator. . . . even the bird that pecked at the fruit in Zeuxis’ picture could applaud.”20

Nonetheless, while Greenberg depreciated the valuation of paintings according to their “success in realistic imitation,” he was silent on the subject of the smooth surfaces necessary to that success.21 And writing a decade later on the subject of Willem de Kooning’s first solo show, in 1948, he admired the thin, smoothly spread paint that “identifies the physical picture plane with an emphasis other painters achieve only by clotted pigment,” and concluded that the artist’s “insistence on a smooth, thin surface is a concomitant of his desire for purity, for art that makes demands only on the optical imagination.”22 We may think it odd that he applauded a method of painting associated with hyperrealist kitsch. What he was arguing for, however, was emphasis on “the physical picture plane” without the use of “clotted pigment” that would appeal to the sense of touch rather than to the optical imagination.

By an intriguing coincidence, Sigmund Freud’s Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905) was published in English translation almost simultaneously with Greenberg’s de Kooning review, and speaks of “seeing—an activity that is ultimately derived from touching.”23 But Freud was a man of the eye and the hand; Greenberg was a man of the eye, and had difficulty with painting “when the eye says a thing is round, and the finger says it is flat.” He wanted both the eye and the finger to say that it was flat.

It is important to note, though, that Ruskin’s aphorism belonged to a broader discussion than the topic of trompe l’oeil. Writing “whenever the work is seen to resemble something which we know it is not, we receive what I call an idea of imitation,” he went on,

Now two things are requisite to our complete and most pleasurable perception of this; first, that the resemblance be so perfect as to amount to a deception; secondly, that there must be some means of proving at the same moment that it is a deception. The most perfect ideas and pleasures of imitation are, therefore, when one sense is contradicted by another, both bearing as positive evidence on the subject as each is capable of alone; as when the eye says a thing is round, and the finger says it is flat; they are, therefore, never felt in so high a degree as in painting, where appearance of projection, roughness, hair, velvet, etc. are given with a smooth surface, or in wax-work, where the first evidence of the senses is perceptually contradicted by their experience.24

In Ruskin’s view, a smooth surface was critical to “imitation” precisely because the volumetric projection and tactility of a subject cannot be simulated in material paint. He was writing in 1843; Chardin had already proved him wrong, and Cézanne among others soon would also. Nonetheless, the increasing materiality of modernist paintings did correspond to the decreasing presence of the imitation of volumetric projection and tactility in many such paintings—and especially of volume: an artist may readily imitate the tactility of a subject on a tactile surface, but will find it far more difficult to imitate volumetric projection there. Hence Greenberg’s continued harping on the importance of flatness in avant-garde painting.25

Escaping the routinely illustrational aspect of nineteenth-century Salon painting, modernism shucked off the illusion of volume to the extent that there were of course counterreactions; too many to discuss here. But any new art of explicit imitation has had some heavy lifting to do to escape association with the Salon. The so-called Photorealism of the early 1970s was commonly treated as a subgenre, and while postmodernism is more forgiving than its predecessor, highly illusionistic works are still viewed with suspicion in some quarters. Although categorical judgments have no place in responsible criticism, some of the grumbling about Weyant’s paintings appears to have come from enemies of “imitation,” associating it with kitsch and the art of the Salons rather than with the avant-garde. Conversely, admirers of her paintings have noticed that the strangeness of their content is made all the greater because it lurks beneath a “perfect” smooth surface—indeed, that its particular strangeness would be compromised if it were thought to be the attribute of a material surface rather than of an act of “imitation.” Moreover, as Ruskin would agree, her paintings could hardly provide the appearance of volumetric projection to the extent that they do except by use of a smooth surface.

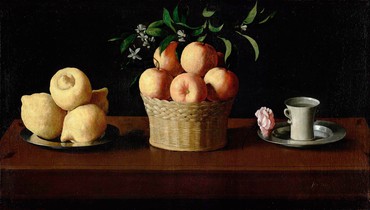

In this respect, Weyant’s still lifes draw inspiration from compositions that set a group of objects on a shelf or ledge, the great period and place of their use being seventeenth-century Spain—in both bodegones, paintings packed with comestible objects, and the simple, spare compositions of painters including Francisco de Zurburán and Juan Sánchez Cotán. At first sight, these latter artists’ still lifes seem as immovable as any trompe l’oeil; and yet, to use Cavell’s apothegm again, “the angel of the odd” floats over them. It would be anachronistic to say that they reveal what Cavell calls “the surrealism of the habitual.” Rather, they have a superrealism that takes simple objects out of the realm of the habitual. Set in bright light against intense dark backgrounds, they seem at once solid and dematerialized: as Mastai observes, “The magnificently delineated forms, chosen in accordance with a mysterious unearthly logic . . . at once fail and transcend the purpose of still life.”26 They have often been compared to offerings set on an altar, especially when they comprise a trio of objects or groups of objects.

This is a familiar type of composition for Weyant, except that hers upturn the meanings of the prototypes: the great Spanish still lifes, set immovably in place in a permanent silence, connote ritual; hers, temporarily frozen in time in their domestic settings, connote mystery. Something strange, even disturbing, appears about to happen—or perhaps something merely mischievous, for her paintings extract amusement from what in other hands might be thought threatening: a ten-ton weight about to fall, party balloons entwined with a string of sausages, glasses breaking in a toast. Beneath what presents itself as innocent, youthful pranks lurks the macabre: indeed one still life does show, reflected in a silver pot, the frozen silhouette of a killer in the kitchen. Yet Weyant calls her still lifes her “happy place,” reassuring us that her art of seductive imitation is an art of make-believe.27

1John Ruskin, “Of Ideas of Imitation,” in Modern Painters 1, chapter IV, 1843; quoted here from Modern Painters by John Ruskin, ed. David Barrie (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), p. 11.

2For a perceptive account see M. L. d’Otrange Mastai, Illusion in Art: Trompe l’Oeil: A History of Pictorial Illusionism (New York: Abaris Books, 1975). See also William Kloss and E. Jane Connell, More Than Meets the Eye: The Art of Trompe l’Oeil, exh. cat. (Columbus, Ohio: Columbus Museum of Art, 1985), and Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, “Trompe l’Oeil: The Underestimated Trick,” in Ebert-Schifferer, Deceptions and Illusions: Five Centuries of Trompe l’Oeil Painting, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2002), pp. 17–37.

3See Emily Braun and Elizabeth Cowling, Cubism and the Trompe l’Oeil Tradition, exh. cat. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022), a catalogue with excellent discussions of both of its subjects.

4See Sasha Bogojev, “Anna Weyant: Welcome to the Dollhouse. Interview and portrait by Sasha Bogojev,” Juxtapoz Art & Culture, July 13, 2020. Available online at https://www.juxtapoz.com/news

/magazine/features/anna-weyant-welcomes-us-to-the-dollhouse/ (accessed May 28, 2023).

5Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993), pp. 61–63. She adds, “being a house within a house, the dollhouse . . . also represents the tension between two modes of interiority.” I concentrate on this subject in my essay “Uncanny Beauty: Thoughts after Seeing Paintings by Anna Weyant,” in the monograph Anna Weyant, forthcoming from Gagosian in the fall of 2023.

6Stewart, On Longing, p. 57.

7Michael Riffaterre, Semiotics of Poetry (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978), p. 69. Quoted here from Stewart, On Longing, p. 180 n43.

8Meyer Schapiro, “The Apples of Cézanne. An Essay on the Meaning of Still-life,” Artnews Annual 34 (1968): pp. 34–53.

9Michel Foucault, Raymond Roussel (Paris: Gallimard, 1963), p. 81. Quoted here from Stewart, On Longing, p. 54.

10Stanley Cavell, “The Uncanniness of the Ordinary,” in Cavell, In Quest of the Ordinary: Lines of Skepticism and Romanticism (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1988), pp. 154, 164, 166.

11See, for example, the photographs illustrated in Peter Galassi, In the Studio: Photographs (New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2015), pp. 102–3.

12Mastai, Illusion in Art, p. 156.

13Ruskin, “Of Ideas of Imitation,” p. 11.

14Emily Braun and Elizabeth Cowling, quoted in David Joselit, “A Counterfeit Illusion,” Artforum 61, no. 5 (January 2023): p. 37.

15Joselit, in ibid.

16Ibid., p. 38.

17Ibid.

18Anna Daly, “Cheap Trick: Trompe l’oeil, photography and kitsch as economies of ‘the real’ in the discourses of modernity,” emaj online journal of art, no. 10 (2017–18). Available online at https://emajartjournal.files.wordpress.com/2018/09/anna-daly_cheap

-trick_emaj10.pdf (accessed July 13, 2023).

19Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” Partisan Review, Fall 1939, repr. in Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 1, Perceptions and Judgments, 1939–44, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago and London; University of Chicago Press, 1986), p. 12.

20Ibid., pp. 6–7, 17–18.

21Ibid., p. 17.

22Clement Greenberg, “Review of an Exhibition of Willem de Kooning,” The Nation, April 24, 1948, repr. in Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 2, Arrogant Purpose, 1945–1949, ed. O’Brian (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1986), p. 229.

23Sigmund Freud, Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, 1905, Eng. trans. James Strachey (London: Imago, 1949), quoted here from The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 7, 1901–1905 (London: Hogarth Press, 1953, repr. New York: Vintage, 2001), p. 156. Discussed in Didier Anzieu, The Skin Ego, trans. Naomi Segal (London and New York: Routledge, 2018), p. 153.

24Ruskin, “Of Ideas of Imitation,” p. 11.

25See, most explicitly, Greenberg’s “Modernist Painting,” in Forum Lectures, 1960, repr. in Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 4, Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957–1969, ed. O’Brian (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1993), pp. 85–94.

26Mastai, Illusion in Art, p. 168.

27Weyant, quoted in Stephanie Sporn, “Anna Weyant’s Botticelli-esque Paintings Are Taking the Art Market by Storm,” Harper’s Bazaar, November 4, 2022. Available online at https://www

.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/a41867684/anna-weyants

-boticelli-esque-paintings-are-taking-the-art-market-by-storm/ (accessed July 14, 2023).

Anna Weyant: The Guitar Man, at Gagosian, rue de Castiglione, Paris, October 18–December 22, 2023