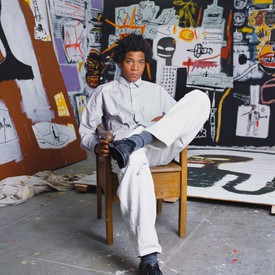

Phoebe Boswell is a multidisciplinary artist who lives and works in London. She embraces the fluidity of language and storytelling as a means to unpack the cultural associations with which bodies of water are imbued. Layers of historic violence and trauma attest to how it continues to bear witness to an inequitable society, while its ebb and flow, its surge and swell, posit water as a site for possible renewal, rebirth, reclamation—a healing, holding, place. Photo: Adenike Oke

British-Ghanaian artist Adelaide Damoah is a London-based multidisciplinary artist who uses investigative practices spanning painting, performance, collage, and photographic processes. Her key areas of interest are anticolonialism, joy, and feminism. She exhibits in national and international galleries and institutions including Gagosian, and serves on the boards of two art charities.

Julianknxx’s work merges his poetic practice with films and performance, engaging in a form of existential inquiry that seeks at once to find ways of expressing the ineffable realities of human experiences and to examine the structures through which we live. His work challenges fixed ideas of identity and unravels linear Western historical and sociopolitical narratives, attempting to reconcile how it feels to exist primarily in liminal spaces. Photo: Marc Hibbert

Péjú Oshin is a British-Nigerian curator, writer, and lecturer born and raised in London. Sitting at the intersection of art, style, and culture, her work shows a keen interest in liminal theory and diasporic narratives. She is the author of Between Words & Space (2021), a collection of poetry and prose, and was shortlisted for the Forbes 30 Under 30 Europe list.

Péjú OshinThe show was titled Rites of Passage, and it considered the idea of liminal space. What are your experiences with this notion, conceptually as well as personally?

Phoebe BoswellA lot of my work exists in the porous space between what we know and what we’re yet to know, what we’ve experienced and what hasn’t become yet. The idea of liminal space is really interesting: as a mental state, it can create a lot of tension because it’s a state of unknowing. But I think that the alternative reading of it, or the alternative sensation of it, is that it’s the space of massive possibility and radical hope. It becomes a space of immense knowledge, a space of everything that has been up till this moment, and also a space where the future hasn’t been tarnished yet, right? If you look at it in terms of who we are in this moment, it’s where we can place memory, and it’s also where we can dream.

JulianknxxIt’s something I’m living out daily. I’ve been looking at the question of what it means to be Krio, from Africa, specifically West Africa, Sierra Leone. We’re made up of the African returnees who came back from Europe, the Caribbean, the Americas, and had to start a whole new identity and language. They had to reinvent modes of representing themselves. There’s this constant movement happening, but the excitement, as Phoebe was saying, lies in all that potential—the potential of shifting and drifting. The Krio people in Freetown created this identity of borrowing as they were moving along; they’ve borrowed literally everything that creates who they are today. And I’m here today because of this borrowed identity—that for me is exciting, and passing that on to my kids to think about feels positive. They are partly Sierra Leonean, partly Zimbabwean, but they were born in England. How they carry on this thing of what’s possible with humanity, how we can think of ourselves not just from a social/political lens, how we move as Black people and own spaces and take what we can without this limiting thought of, I’m this, therefore I should do X. . . . How do you say, No, I will take what I can wherever I’m at—I find that inspiring.

For an artist thinking about identity, thinking about how I present myself visually, there is a level of performance. I’m carrying these things with me into the ritual space, into the spiritual space, and into the physical space. I can bring my ancestors with me. In this space, for me, time and truth don’t matter. I don’t have to care about facts; I’m going to tell these stories in whatever way I can. Because when you look at how many stories white people tell about themselves, who cares about facts?

Adelaide DamoahThere’s so much in what both Phoebe and Julian said that has inspired and added to what I’ve been thinking about in my practice, specifically from the perspective of Sankofa and the idea of understanding your past so that you don’t repeat the same mistakes in the present. It all leads to the question, How can we create another future? Being comfortable in what is known and what is unknown allows for the space to dream, to mythologize. I often use ancestors to mythologize. In this specific work, the ancestors existed at a time when Ghana, which is where they were from, was under British colonial rule, so there’s so much that I don’t know about what they thought and how they lived. That gives me the space for telling a completely new story, where I can ignore or break fixed ideologies and concepts that are no longer relevant, that have held us back in the past, whether that’s with regard to religion, race, or gender.

POLiminality is expansive. It allows for all of these future possibilities. For many of us who identify with this notion of living in liminal space, or constantly being in transition, there is inevitably this idea that you have to accept and expect the unknown, and for that to happen, whether in a small way or in a big way, is paramount.

Before the show was called Rites of Passage, it was called The Space That We Create. While we operate individually, many of us with Black and African diasporic identities don’t operate as singular beings; we often operate in a communal space. What does it mean to operate in a society that promotes the fantasy and supremacy of the singular being, but also, at the same time, to have that very strong sense of wanting to be, or acknowledging that it is important to be, part of a community?

ADWe are social creatures, and the way this capitalist Western world has pushed us into this space of individuality isn’t working for most people, especially after the last couple of years with covid and lockdowns. I feel like we’re now in a place where a lot of artists are crying out for community and connection. Selfishly thinking “It’s all about me” doesn’t work, because no man or woman—especially when part of a marginalized group—is an island. In order for all of us to really get somewhere, we must lift each other up, as opposed to only thinking about the self.

We’re at a critical time when we’re becoming aware of the need for consciousness, all of the tendrils that were already out there in terms of the connections that we all have are tightening up, and we’re all gathering together. And I feel like that’s reflected in what’s happening on the art scene specifically with regard to Black artists, and that’s evidenced in things like Lisa Anderson’s Black British artists photoshoot in London for the BCA [Black Cultural Archives project].

PBEverything mentioned is true, but I also want to say that I think a pressure comes with this idea of Black community—the feeling that we all have to speak the same way, we all have to speak for each other—and there’s something so restrictive about that. The Kenyan writer Keguro Macharia has written a book called Frottage [2019] about the intimacies of Blackness. We talk about Black kinship, but kinship suggests the familial—suggest that we all have the same ideas, and speak in intimate ways that are all affirming of one another. Macharia tries to queer this idea of kinship by calling it “frottage.” There, Blackness doesn’t have to be a thing where we’re all embracing each other in a homogenizing, normative way but becomes something where we can rub against each other, and the rubbing against is where the energy to propel us forward exists. We can read with and read against one another. Frottage exists in the ways we don’t see eye to eye, in the ways we enable each other to have singular points of view and perspectives, while still being completely entwined in this overarching, interlocking rhizome of what Blackness is. As soon as we become a monolith, we’re very easily managed by those who don’t ever want to truly see us anyway.

POI want to clarify and also agree with you, Phoebe. I think the idea of community can sometimes be divisive because it can be a flattening force. Along those lines, I want to speak very specifically to all of your works. I’m thinking about you, Adelaide, and how when we talk about community in the context of your practice, that can mean multiple things for different people: the people who surround you, the people who build you, the people who make you, the people who eventually become a composite group that bestows you with what you are. And then for you, Phoebe, your works in the show are tender and about risk. And then you, Julian, address the idea of the masquerade, which, within our various cultures and communities, may come out at festivals or particular family harvests. What I’m driving at is that there are multiple layers of community that look really different but all feed into this broader idea of interconnectivity across space and time. In truth, it can’t ever be flat, and I think that’s what we’re all working toward.

JThe way I’ve been approaching this project specifically is from the idea of creating a living archive. If the archive is alive, that means it changes—it has to keep being moved and shaped and interrogated and challenged. For me, I can’t legitimately make work without talking to people, so listening becomes a big part, which I enjoy. I have a special love for people telling me stories that can’t be proven [laughter].

PO“I don’t care about the truth anymore” [laughter].

Installation video, Rites of Passage, Gagosian, Britannia Street, London, March 16–April 29, 2023

JExactly [laughter]. I’m interested in memory, how people tell stories of the past and how creatively they do it. My earliest memory of these is the way my grandma would tell me stories of my granddad, whom I never met. So there’s this expansive freedom: I can’t verify these stories, and they carry a special tone or richness because of it.

But community comes into that because you must listen, you know? I’m listening even now, going to different cities and just listening to how Black people talk about their experiences and how Blackness performs in different European cities. People see themselves very differently and it’s wild to me, but at the same time, it’s refreshing.

And when I’m presenting the work, I have to show it to my own close community and allow them to push back on it. This is the only way I know how to make work. Community is part of that. I live in that space, where people are questioning and I’m questioning. And in this work specifically, you see question marks at the beginning of each sentence: that’s because I’m questioning what’s before, but also I’m questioning my question.

PBWe’ve been taught in a Western way to think about knowledge as this kind of hierarchical pillar, when actually, like Julian, I’m more interested in the wisdom of lived experience. Between my experience and your experience, there’s no hierarchy. Returning to liminality, I think the truth lies in the space between all our different lived experiences. For my installation The Black Horizon: Do We Muse on the Sky or Remember the Sea? [2021], I asked fifty people, including you, Péjú, to talk about freedom and what freedom is. I asked the people I read a lot—Saidiya Hartman, Christina Sharpe, Rinaldo Walcott—but I also asked a three-year-old kid, and the three-year-old kid probably has a better idea than all of us about what freedom is, right? Somewhere in the middle of the layering of all of your voices, the person who comes into that work has their own experience and brings their own thing into it; they can somehow determine for themselves through that experience what freedom feels like in that moment, which would change the next time they come in, because then they’d be met with a different set of voices. Community is how we tie together our lived experiences in a way that feels liberatingly kaleidoscopic rather than didactic or binding to any one specific mode of thought.

POAlong these lines, I’d love to get into the dual—or multi—part of your practices. Adelaide, you also have a performance practice; Phoebe, this is a moment in which we are looking at people who are engaging with your written work, and how that can spurn questions around the truth in other ways; and Julian, in your practice with poetry and storytelling, we’re again engaging with inquiry and truth. How do these aspects of your practice provide additional ways in which you might be offering space not just to yourself but to those who are engaging with the work as an opportunity to look at the truth?

PBI’m really interested in the slippage of memory. Whole cultures have been formed around lies and complete memory loss; whiteness is a transmutation of some ideas that some people had that became “truth,” becoming this bind that we all now have to live within, right? So history books are written in ways that make truth out of something that is probably a warped perspective. If you have an agenda around power, then the idea of searching for truth within the rigid lines of a page, or even photographs, and now thinking about AI, with deep fakes—sorry, I’m not even answering your question—everything is up for slippage, which is terrifying . . . and also maybe liberating.

I started writing because I used to want to be superprepped when talking about my work. I’d write artist’s talks, and then I realized it’s kind of a vibe to sit and think about your work dynamically in this other form. And then the writing took on its own power for me, because it became a place where I could slip between the slippage of my own, restless visual practice. I draw, I paint, I make films, I play with sound, interactivity, animation, space, I play with loops and pull people into the work. . . . I ask the work what it needs and I listen to that intuitively and show up as best I can with those tools. It’s both organic and deeply intentional, revelatory, and I’ve found that writing has become this porous middle space between all the the directions my practice is pulling me in, a sort of connective tissue in a breathing, living thing.

JPoetry was my first gesture of self-expression. It was my own private endeavor—just marking or projecting the person I want to be. Over time, I came to realize that what poetry does is condense big ideas. That was appealing, that I can tackle vast concepts with small gestures. Then, if you combine this with the way we tell stories back home—they always come with emotion. If someone’s hosting a funeral, or if they’re hosting a wedding, they break out into songs, they break out into old stories, they’ll break out into some secret that you’re not meant to know about [laughter]. There are these performances that we do on a daily basis. We take them for granted because people said, Oh, to do such and such you have to do it in this way. Embracing all of these things back home then gave me a space and a freedom to say, Oh, I can stand up and read a poem, I’ll break out into a chorus, I can ask friends to come and join me onstage and sing with me. I’m not being a multidisciplinary artist; it’s just what my grandma did, like, you can’t just tell a story. Even during the [Sierra Leone Civil War (1991–2002)], we’d be sitting outside and people would just drop a story. We’re all outside, traumatized, and this guy walks past and goes, “I just witnessed so much blood.” And we were all like, Where, and he says, “It’s running down the hill all the way to the center of the capital city.” He said, “There’s been a big accident.” And we’re like what accident, what happened? This guy, with his serious face, he said, “Yeah, a car just ran over a cockroach so now the blood is just everywhere” [laughter]. And he just went on.

But we needed that. Everyone laughed and then, you know, the next group of people came, they started shooting guns and we all ran, started lying on the floor. These moments, and the way we live our lives as Black people, are as fascinating to me as so much of quote-unquote “high culture.” Or, I was listening to an interview with Arthur Jafa and he spoke about how Black people don’t have to dunk the ball the way we do when we play basketball, but we do it anyways, with flair. It’s like, Why not, you know?

ADI secretly write poetry as well, which slips into my work in the context of performance. Revaluing the Self [2020] was a spoken-word performance. It was a long poem that I wrote, and I made up things, mythologized actual people to create these mythical beings to tell a story that, unless you know me and knew what was happening at the time, just looks like a fictional story, but all of it was based in truth. The Into the Mind of the Coloniser performance [2020] is probably the most obvious one where I was using the truth from a certain perspective. I took the truth from the colonizers’ perspective to bring alive the idea of what was enforced on Africans and other colonized peoples when the whole colonial project was happening: I was reading specifically from the perspectives of these people from texts written at the time. Some of them were instruction manuals of how to colonize people, how to control the natives, so to speak, and as well as very dry truths about how to look after themselves in a tropical environment—the kind of medications to take, the kind of clothes to wear, that kind of thing.

But in addition to exposing truths that most people who were watching the performance would have had no idea about, there was also the presence of myself, a representative of Africa, so to speak, and speaking about the scramble for Africa. I was wearing funeral attire, so it was this mournful expression of a version of truth. We all know that the whole colonial story was a lot more complex than that, but that was one way of exposing one version of truth that most people participating weren’t aware of, and they left feeling shocked. And some people were upset and some people didn’t want to take part. But it was a visceral experience. That for me is really the importance of performance when it comes to trying to tell a story, in that you collapse the space between the audience and the artist to be able to tell a truth, whatever that truth is. It doesn’t have to involve the use of words; it can be just the movement of your body that impacts the audience in a way that’s difficult to get from looking at a static object.

Rites of Passage, Gagosian, Britannia Street, London, March 16–April 29, 2023