Vincent Pécoil is an art historian, writer, and curator. From 2007 to 2017 he was the director of Triple V gallery in Paris. He has curated exhibitions for various institutions in France and is the author of numerous monographic catalogue essays. His writing has also appeared in Art Monthly, Contemporary, Flash Art, Les Cahiers du Musée National d’Art Moderne, Parkett, and Tate Etc., among other publications.

Steven Parrino is missed by many people, but it could also be said that he is missing in a more general sense, like a “missing link”—between Frank Stella, say, and Sonny Barger, the notorious Hells Angels member. It was possible for him to say: “I went to see Raymond Pettibon’s work, and I was thinking about Ad Reinhardt.”1 This quotation is actually a good introduction to Parrino’s own work—to the way in which it fuses two essential currents of recent art: pop culture and the radical avant-garde. He saw himself as a “Bastard Kid of Drella.”2 Indeed, this kid was so much a bastard child that he presented his work as abstract art.

But when it comes to Parrino’s work, the distinction between abstract painting and figurative pop art is irrelevant, for Parrino understood his work as a form of realism, as it was redefined in postwar American art. An important exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1968, The Art of the Real, assembled works by Reinhardt, Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Smithson, Barnett Newman, and Donald Judd in order to highlight this renewed concept of the “real” in art, defining it as a set of facts rather than symbols. E. C. Goossen wrote in the catalogue that “the new work of art is very much like a chunk of nature, a rock, a tree, a cloud, and possesses the same hermetic ‘otherness.’” Painting had become a concrete fact, as concrete as the experience to which it invited the viewer. Almost twenty years later, in 1987, Bob Nickas reappropriated the title of this exhibition for a show he organized at Galerie Pierre Huber in Geneva, in order to suggest that younger artists, including Parrino, were now working along the same vein.3 The realism of Parrino’s art makes the painting itself into an object or a real fact. “Realism has been redefined since Courbet, from representing the reality of the day to defining the object in the real world, real time. Subjectivity is selection (the clean edit) and does not deal with the melodramas of fantasy, just the facts.”4

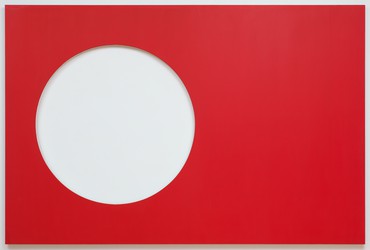

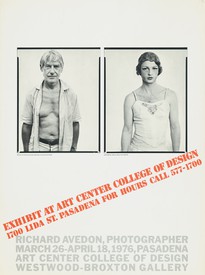

Parrino had a predilection for black, white, and metallic paintings because of their propensity to exploit the real, nonillusionistic properties of light.5 But if Parrino took for granted the objectivist dimension of Stella’s paintings and those of his contemporaries, he also regularly introduced elements into his paintings and their titles that perturb the rationality of this objective self-evidence. For example, certain of his works reinterpret Minimalism’s essentialist (reductivist) quest as analogous to the history of the chopper. Some of the drawings and collages in the current exhibition [Steven Parrino, Gagosian, 980 Madison Avenue, New York, September 25–November 3, 2007] depict this universe—simple drawings of nothing but a reduced form in the shape of a motorcycle transmission belt, circles aligned like starting lights at a racecourse, the insignia of the Hells Angels, or a drawing of Ed “Big Daddy” Roth. Just as Minimalism and its descendants sought formal reduction in order to attain the essence of art, bikers found an original way to reduce their equipment in order to increase its power and speed. In both cases, the search for efficiency worked upon form—a stripping bare or deboning. Parrino extended this parallel by underscoring the fact that choppers were originally outlaw objects, much like his own artwork, which sought to break free from historical canons, inherited conventions, and the interdicts of “high” culture.6

As if this efficiency had been pushed to its limits, Parrino’s paintings seem to have resulted from nothing but accidents. In Parrino’s own terms, his painting is a type of “deformalism,” featuring “deformed” canvases: “By unstretching the canvas, I could pull and contort the material and reattach it to the stretcher, in effect misstretching the painting, altering the state of the painting. The painting was, in a sense, deformed. This mutant form of deformalized painting gave me a chance to speak about reality through abstract painting, to speak about life.”7 Unstapled, folded, and restretched, brutally underscoring their own materiality, Parrino’s paintings disrupt the perfection of their initial state through a process of voiding or the shattering of the picture plane. Frank Stella’s Cat (1992) plays with the relation of its conception and technique to Stella’s black paintings, with their unpainted stripes; but in the process, the work escapes its master, letting the unprimed canvas intrude within the picture plane, disorganizing it into a confused network of folds. This is formalism gone wrong. The spectator is summoned to gaze upon the painting of a disaster.

“That old PUSH/PULL has got to be taken literally. To be an artist, you have to exceed. Failure is better than mediocrity.”8 Such literality translated into the violence that Parrino inflicted upon the canvas, a violence physically exercised upon the painting. Hells Angels (1985) is such a literal application of the formalist push-pull theory that it has turned into something akin to other forms of art linked to action. Indeed, although Parrino is primarily known for his paintings, he also created performances and often played his own music in concert. These performances were improvised, which meant that they were poorly or not at all documented. In Fire Door (1979), Parrino simply left a building by the fire exit after having set off the alarms. In Electric Guitar (1979), he played fifteen minutes of feedback at high volume. Disruption (1981) consisted of Parrino smashing a television set with a sledgehammer. More recently, Trashed Black Box, at Le Consortium in Dijon (1999), was presented with a video showing Parrino at work—in the process of destroying an architectural structure built of plasterboard according to his own instructions. Parrino’s paintings clearly partake in the attitude manifested in such performances. They are “action paintings” of a particular sort, sincere homages to Jackson Pollock—sincere, that is, in Parrino’s sense, respecting the spirit of the original while themselves being disruptions of painting’s status quo. The space of the painting no longer limits or frames the action of painting; it becomes the object subjected to the action, the trace of an accident. In certain of the paintings in the present exhibition, the paint that has dripped over the edges of the canvas might recall the way in which Pollock deposited paint on the canvas, but Parrino materialized the limits of the painting that Pollock’s work seemed to go beyond; he brought the unprimed canvas to the foreground, causing a psychological and physical break with the historically predefined support of painting.

This mutant form of deformalized painting gave me a chance to speak about reality through abstract painting, to speak about life.

Steven Parrino

“My paintings,” Parrino wrote, “are not formalist, nor narrative. My paintings are realist and connected to real life, the social field, in brief: action. . . . All my work deals with disrupting the status quo (and the history of like disruptions—mainly focused on the USA between 1958 and the present time)—my lifetime.”9 One way in which Parrino effected such disruptions was by introducing voids into his paintings, symbolically connecting his work with the real. There are many holes in Parrino’s paintings. And these holes are not circles; they are not abstract figures, but real openings. Spin-Out Vortex #2 (2000) seems to want to swallow up all the space around it, along with its contents, including the viewer. Such gaps can open on either a prosaic beyond or a physical interiority whose sexual content is sometimes explicit. (“You’ve taken the heart out of your painting,” Joel Otterson said of Parrino’s 1986 painting Big Hole.10 )

“The cutting of the canvas, unlike Fontana again (for whom it was a matter of opening the pictural field into the transcendental space of Art), functions therefore as a shifter,” connecting painting to real life and social field.11 In Parrino’s work, painting is no longer simply a window upon the world—a world that one can view only from the other side, the side of art; it is wide open, letting the real world penetrate the space of the viewer. In this sense, Parrino’s work is “realist.” For Stella, painting only led back to painting, but Parrino sought an exit, an outside—not an escape route, but something that would render the presence of paintings even more real. And Parrino tried to attain this exteriority by inducing a number of accidents to intervene upon the painting surface—creases, folds, or hollows. Just as the titles of his paintings function as supplementary “noise” that recalls the noise of the real world, the reality of New York City—“the constant din of Manhattan, all cars, trucks and electricity. . . . Music to my ears, art for my soul, buzzing power chords and feedback”12 —these scorched paintings open on a dark and violent civilization. The Babylon from D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (#5 in Parrino’s EXIT series of drawings, reprinted in his book Exit/Dark Matter)13 provides the background for images that are not “neutral” abstractions: a Union Jack, swastikas, a pillory, or the barrel of a gun. Such images have the effect of stirring up memories of how forms impact the real, the violent return of the repressed within abstraction.

Parrino’s pop monochromes are directly connected to the urban reality that constitutes their environment. But the world glimpsed in and through his work is not the American Dream, but rather its underside, the air-conditioned nightmare. Death in America #2 (2003), for example, echoes Andy Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” works, tragic news clips, racism, and criminality. Many of Parrino’s paintings, like International Style (1983), Disruption (1981), and, more elliptically, Universal Mafia (1992), have a structure that recalls Warhol’s diptychs from the “Death and Disaster” series, where the silkscreened image of a catastrophe, an accident, or a riot, is displayed next to a monochrome panel of the same color. In fact, Parrino’s paintings sometimes explicitly bear the word “disaster” as their subtitle —such as Candy Stevens (Pink Disaster). These are disaster-paintings—literally, painting accidents, the evidence of damage done through the literal application of the push-pull principle—and not paintings of disasters. They are, in short, still lifes—which the French call natures mortes, dead nature: “PAINTING IS DEAD. I saw this as an interesting place for painting. . . . death can be refreshing, so I started engaging in necrophilia . . . approaching history in the same way that Dr. Frankenstein approaches body parts . . . Nature Morte.”14 Parrino envisaged painting as an “assisted readymade,”15 a preexisting object endowed with a second life. Assisted survival, artificial or nonnatural life. The paintings went from natures mortes to natures mortes vivantes: from dead nature to living-dead nature.

Parrino was familiar with the ideas of Stella and Judd, and notably with their holistic convictions about works of art.16 He told Bob Nickas: “The best American art shares a plain logic that is concerned with a whole effect, and has little regard for relational parts that detract from this whole.”17 This statement brings to mind not only Frank Stella, but also Victor Frankenstein: for both Frankies, the whole is more important than the parts (even if the latter are readymades, as is the case with the doctor’s monster). One of Parrino’s drawings incorporates the head of Frankenstein’s creature. Another depicts skulls. The titles of Skeletal Implosion #2 (2001) and It (Blob #1) (1994) bring them closer to the world of The Evil Dead and Stephen King than to that of great art. But in fact, all of Parrino’s “assisted readymades” are ghostly objects, the living-dead: “I have personal reasons for repainting certain paintings BLACK, reclaiming them like so much dead, bringing them power, honor; facing my newly-risen zombie-abstraction, no longer a pure formalism.”18 Parrino thus granted a second life to a stock of his paintings that had been conserved (but not owned) by a Swiss gallerist by repainting them black, destroying them with an electric saw, and then piling them up against the walls of the Centre d’Art Neuchâtelois in 1998. The last solo exhibition of his life, at Team Gallery, where he exhibited The Chaotic Painting (2004), was entitled Plan 9 after Ed Wood’s 1959 film Plan 9 from Outer Space, another story of the living-dead. In the purest American tradition, The Chaotic Painting erupts into the space of the viewer; it shares the viewer’s physical space. The only difference is that, metaphorically, Parrino pushed the space in question and the alterity that Goossen discusses so far that they can be said to come from “outer space,” as if the paintings themselves were spaces from elsewhere, utterly foreign—a very Smithsonian confusion between pictorial space and cosmic space. Painting here becomes an absolute “non-site” (or rather a no-site)—an idea that Parrino himself suggested.

My paintings are not formalist, nor narrative. My paintings are realist and connected to real life, the social field, in brief: action.

Steven Parrino

These appropriations, these “pop monochromes,” are not ironic. “Appropriation as a theoretical distortion. . . . Appropriation is not a parody.”19 The logic at work here is not the “neo-geo” logic of the simulacrum and simulation, nor the postmodernist trope of history conceived as the repetition of tragedy as farce. Parrino often insisted upon this very point: his appropriations and his displacements were not cynical. He saw our epoch as a mannerist period, but he understood this word in a positive sense. Appropriation becomes the form in which painting and abstraction assure their own survival after their “end.” Rather than “simulacra,” it would be more accurate to speak of Parrino’s paintings as “specters.” Specters of abstraction or living-dead paintings. As opposed to the simulacrum (which is the image of an image), the specter maintains a confusion between the living and the dead. Properly speaking, a ghost is neither real nor non-real, neither present nor absent. It does not pertain to ontology, the discourse upon being; it demands its own specific approach—hauntology, to use the neologism coined by Jacques Derrida.20

The first (true) monochromatic works, Alexander Rodchenko’s, were originally intended also to be the last—after them, painting (monochrome or not) was no longer the question; art now had to join forces with industrial production. According to Yve-Alain Bois, the mourning process that characterizes modern painting was never anything but the conjuration of this spirit of the avant-garde, which dreamed of art’s self-dissolution. Ever since, painting has been haunted by the advent of this end and obsessed with the incessant return of the monochrome. A specter is something that comes back, as are all appropriations in art; but as opposed to simple simulacra, one can never tell whether the specter has come or remains to come, whether it is dead or alive, because it is a symptom of an impossible mourning process. Impossible, because what is dead (painting) returns incessantly from the realm of the dead, living-dead.

1Steven Parrino, The No Texts [1979–2003] (New York: Abaton Book Company, 2003), p. 40.

2Bastard Kids of Drella [Part 9] is the title of an exhibition that Parrino organized at Le Consortium, Dijon, in 1999, which assembled an imaginary family, like the Ramones, supposedly made up of the bastard children of Andy Warhol, such as Diana Balton, Michael Lavine, Jackie McAllister, Tam Ochiai, Amy O’Neill, Lisa Ruyter, Helen Sadler, and Blair Thurman.

3The show included, among others, Steve DiBenedetto, Matthew McCaslin, Allan McCollum, Peter Schuyff, and Wallace & Donohue.

4Parrino, The No Texts, p. 21.

5Parrino, The No Texts, p. 36: “Black, white and aluminum are elemental non-colors that exploit light in an actual manner.”

6“Conversations avec Steven Parrino,” excerpts from a film by lvo Zanetti, Palais (Palais de Tokyo, Paris), no. 3 (2007).

7“Parrino,” in Jeanne Greenberg and Bob Nickas, eds., Altered States: American Art in the 90s (St. Louis: Forum for Contemporary Art, 1995), p. 7.

8Parrino, The No Texts, p. 23.

9Lionel Bovier, unpublished interview through fax correspondence with Parrino, 1994. The author wishes to thank Lionel Bovier for sharing the transcript of this correspondence—originally edited by Parrino—with him.

10Parrino, The No Texts, p. 17.

11Bob Nickas, ed., The Art of the Real (Geneva: Galerie Pierre Huber, 1987), p. 28; this is a citation chosen by Parrino to speak of his own work.

12Parrino, The No Texts, p. 34.

13Published by JRP, Geneva, and Les presses du réel, Dijon, in 2002.

14Parrino, The No Texts, p. 43.

15Bob Nickas, “Anxious Objects: Parrino, Stahl, Wachtel” (interviews), Flash Art, no. 132 (February–March 1987), pp. 101–02.

16An excerpt of the famous discussion between Bruce Glaser and Donald Judd was reprinted in Bob Nickas, The Painted Desert (Paris: Galerie Xippas, 1991).

17Nickas, “Anxious Objects,” pp. 101–02.

18Ibid.

19Ibid.

20Following Derrida, Hal Foster suggested that this phantomatic condition pertains to much of today’s art. See Hal Foster, Design and Crime and Other Diatribes (London and New York: Verso, 2002), pp. 134–37, and Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx, trans. Peggy Kamuf (New York: Routledge, 1995).

Artwork © Steven Parrino, courtesy Parrino Family Estate; text © Vincent Pécoil; originally published in Steven Parrino, exh. cat. (New York: Gagosian, 2007), on the occasion of the exhibition Steven Parrino, Gagosian, 980 Madison Avenue, New York, September 25–November 3, 2007