Daniel Spaulding is an assistant professor of modern and contemporary art at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He previously worked in the curatorial department of the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. He is a founding editor of Selva: A Journal of the History of Art.

There are no circumstances under which the encounter between one human body and another can be an uncomplicated affair. Bodies are strange because people are strange, to their counterparts and to themselves. The occupation of a fleshly vessel is the work of everyone’s lifetime. It ought to be expected, then, that artists—more or less transhistorically, and everywhere—would be concerned with this fact. Of course, they have been, in their own ways: the ductus of a classical Chinese landscape painting has everything to do with the reach of hand and wrist, bone and sinew, and thus is bodily, too, even in the absence of depicted figures. A Chinese painter’s hand channels qi from one part of the cosmos to another, specifically from flesh to silk or paper. But only in the European tradition did unclothed skin become the matter of a centuries-long obsession.

That obsession was on full display in The Renaissance Nude, a show that opened in October 2018 at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles (it then traveled to the Royal Academy, London, from March to June of 2019). The artworks were Italian, German, French, and Netherlandish, all dating from 1400 to 1530. Renaissance nudes pop up in a range of guises: Christian martyr, antique god, allegorical personification, object of desire (or fear), anatomical specimen—or more than one such identity at the same time. To tally up the roles is to generate a matrix of possible meanings for “the nude,” meanings that, in the Getty’s galleries, came to look both richer and more bewildering through their juxtaposition. The show’s great achievement, then, was to have amassed a corpus of evidence on a scale unlikely to be repeated for generations.

To my mind, however, neither the exhibition nor its catalogue answered the most basic question that one can put to the theme.1 Namely: why is it that over the course of the fifteenth century the unclothed body, after a millennium of relative neglect, again became a fixed symbolic form in Western culture (a position it would maintain for nearly half a millennium to come)? Strangely few art historians have attempted an answer. Kenneth Clark’s book The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, from 1956, is still the paramount reference.2 His distinction between the “naked” and the “nude”—between raw corporeality and its idealized form—has survived his own reputation’s (partial) eclipse.3 Following Clark, it has for many decades been taken for granted that the genre of the nude exists to sublimate flesh and to control the anxieties attendant on sex. The nude is the form in which the body can be made available for respectable aesthetic delectation; pleasures otherwise taboo survive beneath classicist drag. It’s a thesis convenient to Freudians, feminists, and classical aesthetes alike, thus seemingly unassailable.4

The project of normalizing the unclothed body in art was curiously speculative. Some sincere Renaissance reconstructions are accordingly more bizarre than any Surrealist contrivance.

One remarkable thing about The Renaissance Nude is that it lent very little credence to this opposition. Bodies here were shot through with nonideality. Or, rather, they showed how malleable the “ideal” has always been. What’s more, negotiation with idiosyncratic flesh seems to have been the stuff of the ideal right from the start, that is, from the early years of the fifteenth century. Where was the sublimated nude to come from, after all? “Classical statuary” is the obvious response. Yet the classical relics were colorless, incomplete. A great deal was left to fill in. Nudity was not a fact of everyday life for late medieval Europeans, as it had been for ancient Greeks—or Greek males, anyway. The project of normalizing the unclothed body in art was curiously speculative. Some sincere Renaissance reconstructions are accordingly more bizarre than any Surrealist contrivance. Just look to the early-sixteenth-century Netherlandish painter Jan Gossart (well-represented in the Getty show) for evidence that strident classicism is no barrier to Eros gone wild.5 Gossart’s strangeness stems not from ignorance of Renaissance corporeal canons but rather from their hypertrophy. Every muscle, every breast, every toe and finger is extruded as if to concentrate its barely sublimated sexual charge; lest we miss the point, oversize accessories pick up the theme (consider the hectoringly phallic club in his Hercules and Deianira of 1517). If John Currin has a lineage, it is here.

Gossart is admittedly an extreme point in a many-sided dialectic. Now take another: the Florentine painter Piero di Cosimo, who lived from 1462 to 1522. His Discovery of Honey by Bacchus was in the Getty exhibition. Dating from around 1499, the work is one of a series of mythological spalliere—horizontal paintings made to hang above furniture in the palaces of Renaissance Florence—that the artist produced from the 1480s to close to his death. It was probably commissioned for the bedroom of the Florentine courtier Giovanni Vespucci, a younger relative of Amerigo, the explorer, together with the singularly unpleasant pendant known as The Misfortunes of Silenus.6 Like most of Piero’s spalliere, these panels fantasize primal scenes of culture set in a remote, unspecifiable past. The subject of Discovery derives from Ovid’s Fasti, a compendium of early Roman lore; the followers of the wine god Bacchus make noise to draw bees into a tree.7 Honey will be their reward.

Piero’s mythologies are truly, deeply weird pictures. They are, to begin with, weird in the straightforward sense that there is nothing else that looks much like them. He has no close peers in the Renaissance. (In an important 2006 monograph, Dennis Geronimus aimed to “de-stigmatise Piero” without “over-normalising” him. That’s about as much as can be done.)8 It isn’t, of course, that other artists were unconcerned with the primitive, let alone with myth. But there is no other Renaissance painter who went so far in the imagining of an unfamiliar lifeworld. In Piero’s art, classical learning is estranged via its materialization. He was a realist of the bizarre; whereas most of his peers looked to the classical past for models of ideal form, he preferred to poke around in obscure legends, which he then painted as plausibly as he could. Erwin Panofsky, the artist’s most influential interpreter, writes that Piero “felt the tangible epidermis of things, rather than their abstract form.”9 His work’s power has more to do with unmotivated reality-effects than with his paintings’ nominal iconography. The latter is in any event often inscrutable.

The satyr was one of the great creaturely forms the Renaissance had inherited from classical antiquity and then reimagined as suddenly, differently alive.

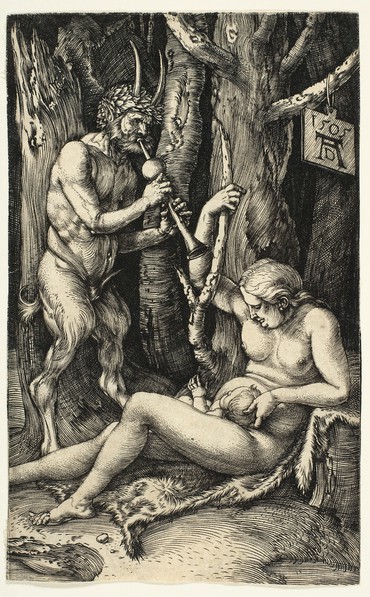

Some of his iconography is less abstruse, though. We can be sure that satyrs dominate Discovery of Honey. The satyr was one of the great creaturely forms the Renaissance had inherited from classical antiquity and then reimagined as suddenly, differently alive. Around 1500 it was the subject of widely distributed prints by Albrecht Dürer and Jacopo de’ Barbari, which are distinguished from antique models by focusing more on the creature’s domestic life than its monstrosity; the theme pops up in other mediums as well, such as sculpture. Satyrs populate an imaginary universe alongside nereids, nymphs, maenads, and other energetic women. (The early-twentieth-century art historian Aby Warburg used the term nympha to refer to such figures.) Piero himself stage-managed civic festivals at which performers dressed up as satyrs and cavorted on stilts. Satyrs were not quite imaginary creatures around 1500, then. Most citizens of Florence would have seen them in the flesh on the great religious feast days, in a mingling of the Christian and the pagan.

Bacchus is the smiling figure at lower right. His thyrsus staff is blown up to the proportions of a Herculean club (shades of Gossart) and his consort Ariadne is beside him. Their entourage has come upon a swarm of bees, which they are coaxing to a hive in the branches of a barren yet anthropomorphic tree, using noisemakers to guide their path. An adult satyr and his infantile companion have scaled the tree’s left branch. What exactly the older satyr is doing is hard to say; evidently some fussing with a ladle-turned-bell, either as a last bee-herding maneuver or as preliminary to extracting the honey itself. This is tricky work: he is busy correlating means to ends. If he fails, the whole project may turn out to have been pointless. The climbing satyr is the painting’s key figure, then. But his meaning emerges only in contrast to the action below.

What’s moving about the painting is the detail with which Piero imagines this larger collectivity. Even if his figures are outlandish and often inhuman, they all the same invite identification; simply put, they do things with their bodies that we viewers can imagine ourselves doing too. Some satyrs are filing in at left. They hold makeshift noisemakers. Two human women—specifically maenads, female followers of Bacchus—are in the mix as well. This apparently easy commerce between beast and Homo sapiens helps domesticate the former. Other satyrs lounge about, or shadow Bacchus and his fat friend Silenus (a rare satyr with a name), who is seated on a donkey at right. The squatting individual (maybe Pan) in the lower right foreground holds three onions, which were considered an aphrodisiac at the time. A further babyish satyr is taking a nap in the tree’s hollow. I am reminded here of the richness of the term “form-of-life” in the writings of the philosopher Giorgio Agamben and of the French collective Tiqqun. “Form-of-life” is contrary to “bare life,” Agamben’s more famous concept. Where bare life is stripped to mere unqualified persistence, a form-of-life is “a life that can never be separated from its form,” one that exists only insofar as it takes on a style, a pattern or inflection. We only live richly in the stylization of collective habits, which are potentialities rather than limits. As Agamben puts it, his term “defines a life—human life—in which the single ways, acts, and processes of living are never simply facts but always and above all possibilities of life, always and above all power (potenza).”10

In Discovery of Honey, however, this life is not human—or, rather, it slips in and out of humanness. Not only that, but the slippage happens in the most irreducibly specific of the painting’s moments. Take the dark, discursive satyr at lower left. He turns to his female companion, who is an epitome of worried care. What he says to her can’t be guessed. It may be trivial: even as she listens to whatever the dark satyr has to say, she goes on suckling her satyr baby. Instinct and speech modulate each other. The condition of the male partner’s talkative indolence is his interlocutor’s state of concern. The latter sums up the labor of what certain feminists call “social reproduction”: the often invisible work that goes into the maintenance of sociality tout court—taking care of babies, for example. And that work is difficult, constant, a balancing act in the midst of other things. To lounge on a blanket (do satyrs make blankets? Odd that they have blankets but no clothes); to do so, and to prop oneself up, turn, recognize speech, and in the surprise of hearing that speech attend to it, on the off chance that it might be important, and unthinkingly to allow one’s limbs to sprawl and deform, even while maintaining contact with a needy child: these are achievements of nature and culture at once, of a culture founded on nature’s necessities and a nature bent to the needs of a social universe. For all the Virgin Marys in Renaissance painting, there are few images of nursing mothers quite like this.

Of course the picture is comic. Piero doesn’t mean us to take satyr life too seriously, though perhaps a little more seriously than his cutout Bacchus. But life is comedy, after all, so it doesn’t seem out of place to detect serious thought on the artist’s part about what it means to live with others in a shared lifeworld, exposed to each other’s strangeness (as with Pieter Bruegel the Elder, whose peasant paintings magnify Piero’s note of weird, specific ordinariness—weird, in part, precisely in attending to ordinariness, in an age before the full bloom of secular genre painting).11 Satyrs are useful because they defamiliarize the background noise of (human) sociality.

Walter Pater once wrote that in the figure of Adam in the Sistine Chapel “there is something rude and satyr-like, something akin to the rugged hillside on which it lies.”12 Piero’s climbing satyr is evidently the inverse: not the human dragging nature into consciousness but the animal scrabbling toward humanity. I may be projecting too much teleology, though.

If Discovery of Honey is an image of the primeval, what does this say about Piero di Cosimo’s, or his culture’s, idea of it?

This is the picture’s conceptual problem. If Discovery of Honey is an image of the primeval, what does this say about Piero di Cosimo’s, or his culture’s, idea of it? Piero’s mythologies are almost exactly contemporaneous with the European discovery of the Americas. Rumors of this New World almost certainly would have reached him by the time the Vespucci panels were in the studio.13 Whether or not he was directly inspired by Columbus, what is certain is that his visualizations of early human history drew upon a late-medieval stock of legend and literature from which Europe’s (calamitous) imagining of the “Indies” would soon enough take sustenance. The painting is direct about this contrast of civilization with its other. At top left is a neatly ordered city, while at right still-savage satyrs clamber up trees. There may be smoke at the top right corner, too. Another of Piero’s spalliere, in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, depicts a forest fire: animals flee from primordial wood to manicured pasture.

The presumed progress from the earlier to the later state is the keynote of Panofsky’s reading of the work. He assigns Bacchus the role of civilizer, since this god brings knowledge of viticulture. Satyrs are a rung in a ladder that leads to civilization; their tree-dwelling cousins demonstrate the alternative. Yet in Panofsky’s reading, Piero was “sadly aware” of lost innocence: “He joyfully sympathized with the rise of humanity beyond the bestial hardships of the stone age, but he regretted any step beyond the unsophisticated phase which he would have termed the reign of Vulcan and Dionysos. To him civilization meant a realm of beauty and happiness as long as man kept in close contact with nature, but a nightmare of oppression, ugliness and distress as soon as man became estranged from her.”14 Panofsky also remarkably surmises that Piero’s primitivism is, as it were, sincere rather than affected: “In his pictures, we are faced, not with the polite nostalgia of a civilized man who longs, or pretends to long, for the happiness of a primitive age, but with the subconscious recollection of a primitive who happened to live in a period of sophisticated civilization.”15 Satyrs might as well be post- as precivilizational.

This is a more telling admission than it seems. Panofsky mistakes Piero for too much a dialectician of enlightenment. The artist’s melancholy is the melancholy of history itself: knowledge of what is lost. However, in countenancing the “subconscious recollection of a primitive” Panofsky also suggests the real persistence of the primitive in the modern, its contemporaneity with civilization. The next step, which he does not take, would be to recognize the viability of a form-of-life that (happily) fails to conform to the European mode of the human. Panofsky is unwilling to admit that Discovery of Honey might in some fugitive way elude Europe’s civilized/savage binary altogether; he is unwilling to grant autonomy to the “semicivilized” itself. It is certainly true that the tree-dwelling satyrs are unenviable, but the pathos of the composition’s central and largest figures has little to do with one’s impression that they are on the path to the completed acculturation semaphored by the parapets at upper left. It is rather that Piero fixes his sentient beings at a moment prior to the fulfillment of that destiny—a moment in which satyrdom is nonetheless evidently self-sufficient and complete as a form-of-life. This is one exit from the West’s drastically limited idea of the human. If Bacchus is a culture hero, as Panofsky argues, then he is a pointedly ineffective one. His stupid grin gives it away. Better to linger with the climbing satyr not quite finding his civilized feet.

1Thomas Kren, Jill Burke, and Stephen J. Campbell, eds., assisted by Andrea Herrera and Thomas DePasquale, The Renaissance Nude, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2018).

2Kenneth Clark, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form (London: John Murray, 1956). Jill Burke’s The Italian Renaissance Nude (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018) promises to become a new standard text, however. Burke was involved in planning the Getty exhibition.

3Clark is the only art historian singled out for criticism in John Berger’s television series Ways of Seeing and in the book of the same name (London: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books, 1972). Yet Berger fundamentally accepts the naked/nude distinction, even as he dismantles Clark’s patrician presumptions. Subsequent feminist art historians, some making use of the concept of the “male gaze” that was developed in 1970s film theory, have even more thoroughly deconstructed Clark’s heteronormative framework, while likewise often reiterating the quasi-structuralist dyad of raw nakedness and culturally coded nudity. At the conference “The Global Nude in the Pre-Modern World,” held at the Getty Museum in conjunction with the Renaissance Nude exhibition, Clark was the object of a heated debate, not to say a pile-on: nearly the entire body of scholars was ranged against him, with precious few defenders holding out. Negative as his reception may have been over the past forty years, the degree to which he remains an inevitable point of reference is all the same remarkable.

4A particularly good study of classicism’s psychosexual travails can be found in Alex Potts, Flesh and the Ideal: Winckelmann and the Origins of Art History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994). In the 1980s, another Clark—the art historian T. J.; no relation—published an influential reading of Édouard Manet’s 1863 painting Olympia, which scandalized the bourgeoisie by delivering a proletarian (“naked”) female body to the Paris Salon, the realm of the classicizing (“nude”) courtesan. In T. J. Clark’s remarkable phrase, “the sign of class in Olympia was nakedness.” Clark, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), p. 146. Though more sophisticated than Kenneth’s, T. J.’s account trades on a similar duality.

5Jan Gossart is the subject of an important recent monograph that argues for his role in the imagining of a specifically Northern (that is, non-Italian) classical style: Marisa Anne Bass, Jan Gossart and the Invention of Netherlandish Antiquity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016).

6This panel, in the Fogg Museum at Harvard, unfortunately did not travel to the Getty. Even accounting for its much worse state of preservation, Misfortunes could never have been as rich a painting as Discovery: it has a rougher and less sympathetic sense of humor, approaching the merely grotesque. It also mostly lacks satyrs, which are my object of interest here. The work’s iconography, though, helps to confirm the pendant’s provenance. The name “Vespucci” is related to the Italian word for wasps (vespe), which feature on the family coat of arms. In the Fogg painting, wasps attack an upended Silenus, in sharp contrast to the benign bees in The Discovery of Honey.

7Erwin Panofsky, “The Early History of Man in Two Cycles of Paintings by Piero di Cosimo,” in Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance (New York, Evanstown, and San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1972), pp. 62–63.

8Dennis Geronimus, Piero di Cosimo: Visions Beautiful and Strange (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), p. 3.

9Panofsky, “The Early History of Man,” p. 33.

10Giorgio Agamben, “Form-of-Life,” trans. Cesare Casarino, in Paolo Virno and Michael Hardt, eds., Radical Thought in Italy: A Potential Politics (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), p. 151. The phrase “form-of-life” was originally Ludwig Wittgenstein’s.

11Compare these observations to Joseph Leo Koerner’s recent book Bosch and Bruegel: From Enemy Painting to Everyday Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, and Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2016). Koerner points out that what we know as genre painting (images of everyday life, without religious or mythological pretext) first emerged in the interstices of monstrous, infernal scenes such as Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1500). Visualizations of life in this world thus originally pertained to the “enemy,” Satan.

12Walter Pater, The Renaissance, 1873 (reprint ed. New York: The Modern Library, n.d.), p. 62.

13As Carlo Ginzburg points out. Ginzburg, “Hybrids: Learning from a Gilded Silver Beaker (Antwerp, c. 1530),” in Andreas Höfele and Werner von Koppenfels, eds., Renaissance Go-Betweens: Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2005), pp. 125–27.

14Panofsky, “The Early History of Man,” p. 65. Some years later Thomas F. Mathews contested Panofsky’s reading, stressing love symbolism over the evolutionary theme: Mathews, “Piero di Cosimo’s Discovery of Honey,” The Art Bulletin 45, no. 4 (December 1963), pp. 357–60.

15Panofsky, “The Early History of Man,” p. 67.