Gillian Jakab is an editor, online and print, of Gagosian Quarterly and has served as the dance editor of the Brooklyn Rail since 2016.

What do you get when you cross a master choreographer, a luminary painter, and a virtuoso composer with a legendary poet?

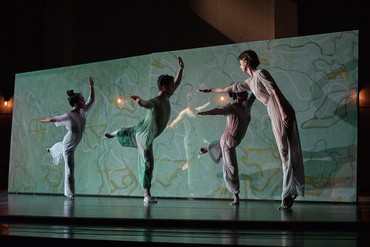

In the recent stage production Four Quartets, Pam Tanowitz’s choreography, Brice Marden’s paintings, and Kaija Saariaho’s score coalesced in a surprising interpretation of T. S. Eliot’s mystical poem. The production earned the highest praise possible, with Alastair Macaulay, in his farewell essay as chief dance critic for the New York Times, calling it “the most sublime dance-theater creation this century.”1 This harmonious intermingling of talent across the arts prompts a look back in dance history—and cultural history in general—to Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, a singular force uniting artistic titans from diverse disciplines at the dawn of the twentieth century.

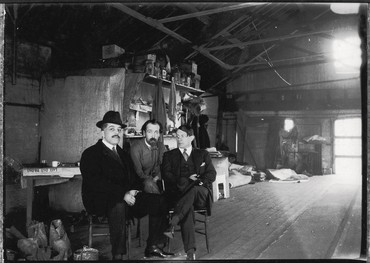

Eliot himself was certainly familiar with the Ballets Russes: he attended the company’s performances and they reverberated through his writings.2 Born from the group of artists affiliated with the Russian journal Mir Iskusstva (World of art), founded by Diaghilev in 1898, the Ballets Russes, from its beginnings, engaged painters, writers, and composers with the long-neglected art of dance. Diaghilev and his dancers propelled ballet into the twentieth century, pulling it abreast with avant-garde movements in the other arts, not least by partnering with them. Yet as dance historian Lynn Garafola notes in the definitive work on the company, its story is far more complex than a recipe of joint creation by equal partners.3

Interviewed for the Gagosian Quarterly online, Brice Marden named the collaborative aspect of the Four Quartets project as the source of his interest in it.4 His interviewer was Gideon Lester, the artistic director of Bard College’s Fisher Center and the man behind the commission. Experienced in playing Diaghilev’s impresario role, Lester clearly has an eye for affinities and complements. Sometimes, however, grouping big-name talents is not enough. Reviewing this summer’s multidisciplinary dance production Dragon Spring Phoenix Rise at Manhattan’s Shed for the Financial Times, for example, Apollinaire Scherr writes that “each member of the artistic team . . . is certified best of the best of their kind” and calls the venue’s artistic director “Diaghilev-ish,” yet the result “counts for less than the sum of its parts” to the point where it “serves as a cautionary tale.”5

Why do some dream teams coalesce while others flounder? The power of the artists’ personalities, the resonances (or lack of) between their ideological and their aesthetic values, their sense of the communicative power of particular art forms, and the skill of the overall impresario—these are some of the determining elements. To peel back the curtains of certain Ballets Russes collaborations and peek at their behind-the-scenes dynamic, I went from coffee with Garafola at Columbia to the Palais Garnier archives in Paris.

The history of the Ballets Russes is in part a history of partnerships between the company’s vanguard choreographers and an A-list of early-twentieth-century painters and composers: Léon Bakst, Salvador Dalí, André Derain, Giorgio de Chirico, Natalia Goncharova, Juan Gris, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and many others, as well as Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, and Igor Stravinsky. Some Ballets Russes creations, such as Pétrouchka (1911) and Les noces (The Wedding, 1923), have become classics of the ballet canon; others may be known today less as dance productions than as slides in an art history course; and still others are forgotten or were never realized at all. Even in their time, some offerings of the Ballets Russes were better received than others. Picasso’s creations for Parade (1917) are a landmark of modernist visual art in ballet; the oft-cited examples of flawed collaborations are some involving Dalí, whose personality and vision often overpowered the choreography.

Garafola demonstrates that the artists more often than not carried out their part of the work without being co-visionaries. “Far more than collaboration,” she explains, “what held together the pieces of Diaghilev’s best works was the community of values to which their contributing artists subscribed.”6 This does not mean that Diaghilev adhered to one artistic movement or a single belief system. Rather, the visual, musical, and choreographic elements of the ballets ebbed and flowed with the various incarnations of modernism from which Diaghilev’s artists emerged. Nor does this mean that they all came from the same movement or subscribed to the same aesthetic philosophy; in fact, even in a single work, they often represented different artistic perspectives. When Vaslav Nijinsky, a brilliant dancer and Diaghilev’s choreographic protégé, shocked Paris society with Le sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913)—famous for signaling a modernist turning point with its angular neoprimitive movement and Stravinsky’s heavily rhythmic, dissonant score—the painter Nicholas Roerich’s stage designs and costumes depicted the ballet’s ancient pagan rituals in the company’s earlier Symbolist style.

Two examples make for good deep dives. Bronislava Nijinska’s collaboration with Goncharova matched the first woman visual artist, and an avant-garde artist at that, to contribute to a Ballets Russes production, Les noces, with the company’s only woman choreographer; and the pairing of Matisse with Léonide Massine on Le chant du rossignol (The Song of the Nightingale, 1920) sheds light on the relationship of art and dance and produced the first examples of Matisse’s cutout technique.

While Four Quartets was playing at London’s Barbican in May 2019, the city’s Tate Modern was preparing to open the first British retrospective of Goncharova’s work. This major exhibition ended with an entire room devoted to her designs for the stage, noting the onset of her international fame after her productions for the Ballets Russes. Like Diaghilev’s company, Goncharova was as versatile and fluid as she was radical. The Tate exhibition highlighted her “everythingism,” a term coined by the painter Mikhail Larionov and the writer and artist Ilia Zdanevich “to describe the diverse range of Goncharova’s work and her openness to multiple styles and sources.”7 The artist’s range allowed her to roll with the tides of collaboration where others might have held fast to their moorings, to destructive effect.

Goncharova’s first Ballets Russes collaboration, the opera/ballet Le coq d’or (The Golden Cockerel, 1914), paired her with the choreographer Michel Fokine. Her colorful sets and costumes, drawn from Russian folk tradition, combined with Fokine’s supple and curvilinear choreography to give fashionable prewar audiences the orientalist visions they so desired, but here found expressed through Goncharova’s fragmented Cubo-Futurist style. These visual choices commanded attention and, according to Garafola, made the ballet “the one genuine success of the 1914 season.”8

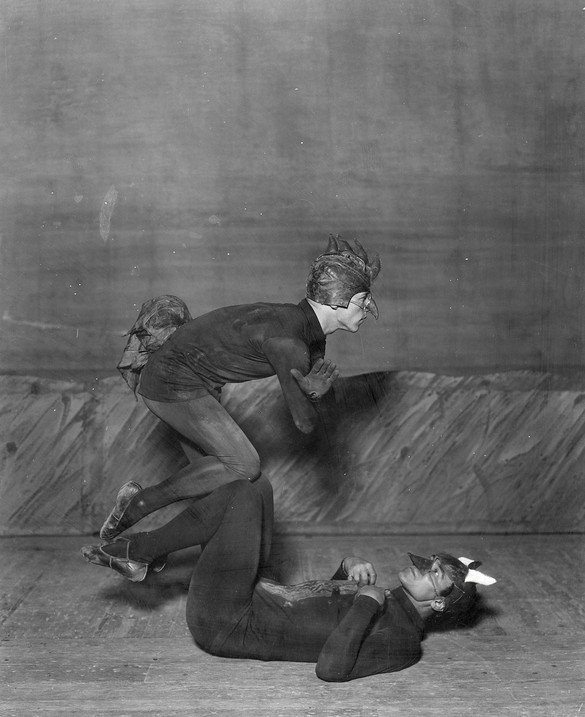

Goncharova’s 1923 collaboration with Nijinska on Les noces was markedly different, both in the relationship of dance to visual art and in the work’s aesthetic. Minimalist and muted, the visual design played an understated supporting role for Nijinska’s bold choreography. Nijinska had a clear vision for the piece and held her ground during the collaborative process.9 The collaboration benefited from Goncharova’s range and flexibility, Nijinska’s sensitivity to visual art, and the values the two artists shared through their personal histories. But it did not just fall into place. As Goncharova later wrote, “By what miracle (I cannot find another word) did the performance of Les noces become so perfectly balanced, so that the part of each collaborator completed those of the others, in spite of the fact that each worked without much thought of the others and without knowing their intentions or the path they were following?”10

The “miracle” was Diaghilev, whose skillful mediation averted a potential irreparable clash. According to Nijinska, after visiting Goncharova’s studio with Diaghilev she let the impresario know that she could not work with the artist’s colorful designs for Les noces.11 Diaghilev initially quipped that in that case she wouldn’t be part of the project, but he let Nijinska realize her conception. In Goncharova’s account, she herself sensed that her original designs were off and worked toward a deeper understanding of what was at stake choreographically.12 After some hints from Nijinska through the go-between of Diaghilev, she peered beyond the jovial facade of a country wedding to the cruelty of marriage predicated not on love but on necessity. The story exemplifies a valuable attribute of Diaghilev’s, his keen judgment as to when to make demands of an artist and when to let the artist take the reins. Facilitating a delicate balance of autonomy and exchange through studio and rehearsal visits, the impresario allowed the choreographer to steer without turning the painter into a passive passenger.

As two women raised in provincial Russia, making their art in a man’s world, Nijinska and Goncharova shared childhood cultural referents and a sensitivity to the plight of women. Les noces took on a kind of protofeminist character, reworking traditional gendered steps, such as pointe work, to eschew conventional balletic depictions of femininity. Goncharova’s final design lamented the somber, preordained path of a young woman toward marriage with gray-scale and earthen colors, uniform in tone. The artists’ shared sensibilities, arguably feminist dispositions, and each one’s belief in the expressive power of the other’s forms served to harmonize their contributions to Les noces—that, and Diaghilev.

Perhaps even more than Goncharova and Nijinska, Matisse and Massine shared a deep interest in one another’s art. In 1909, the same year the Ballets Russes first appeared on the Paris stage, Matisse created La danse I, his iconic painting depicting the incarnation of movement and color through figures dancing in a circle. For Massine’s part, his interest in visual art began in his childhood in Russia. As a young ballet student, he enrolled in an art school to study painting and drawing, and “in this warmly supportive environment . . . began to familiarize himself with the works of such artists as Van Gogh, Degas, and Toulouse-Lautrec.”13 This was 1912, the year before Massine was discovered by Diaghilev, who opened his eyes to the radical developments of twentieth-century modernism. Of all the Ballets Russes choreographers, Massine most closely shared Diaghilev’s attraction to the visual arts and often found inspiration for dance movement in museums. After his formative collaborations with Picasso on Parade, Le tricorne (The Three-Cornered Hat, 1919), and Pulcinella (1920), he was ready for more.

One might expect that Matisse’s lifelong fascination with the rendering of movement would make him receptive to a ballet collaboration. But when Diaghilev approached him—first around 1918, for a remake of Scheherazade (1910), and again a year later for Le chant du rossignol—Matisse was reluctant, protesting that the project would take time away from his painting.14 Again, it was Diaghilev who saved the day. An astute psychologist and infinitely persuasive, he convinced Matisse to view the ballet collaboration as a laboratory for his easel work.

Diaghilev’s influence, it would turn out, ran deeper. Le chant du rossignol did indeed allow Matisse to experiment; the costumes’ geometric textile cutouts marked the first instance of the celebrated technique that would reappear in the work on paper of the artist’s final years. But the production met mixed reviews and the experience soured Matisse to ballet design generally. When Diaghilev dispatched the painter Juan Gris to follow up on a proposal for another project in the early 1920s, Matisse was so cold to the idea that Gris played the exchange as if the Ballets Russes director hadn’t sent him with the sole purpose of persuasion.15

Time healed the wound, however; the seed Diaghilev had planted bore fruit again after his death, in 1929. In 1939, Matisse designed the sets and costumes for Rouge et noir (Red and black), a ballet choreographed by Massine for one of Diaghilev’s successor companies, the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo. Although Matisse had refused again and again to work with the Ballets, he and Massine remained close friends, with the choreographer paying him weekly Sunday visits while the company was in residence in Monte Carlo. The story goes that Massine was one of the first to arrive at a small, informal showing of Matisse’s Dance mural (1932–33) before it was shipped off to the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania, and declared “that Matisse had embodied his dream of what dance should be.”16 Designed to fit into the bays of three vaulted windows, the mural consists of corresponding arched panels. Only parts of the dancers are visible, as if the viewer were gazing into another world beyond the windows; limbs curve and stretch behind the archways in color blocks of pink, blue, and black. Later, Massine pleaded with Matisse to translate the mural into a design for a ballet. The choreographer would recall, “I pointed out to him that [the mural designs] were very similar in conception to the ballet I was planning, which I visualized as a vast mural in motion. He became suddenly very interested.”17

And so, after twenty years, the two artists reignited their collaboration and the rhythm of architecture, dancing bodies, and color of Matisse’s Dance became the basis of his stage design for Rouge et noir. Matisse incorporated the vaulted archways into the set, framing the dancers on a large scale. The costumes consisted of unitards punctuated by geometric designs in primary colors. The effect was as Massine predicted: an abstract painting in motion. And just as Diaghilev had done in his contract with Matisse for Le chant du rossignol, archived in the Palais Garnier, Massine insisted that the artist create the curtain and sign the fabric.

These two artists had careers that pioneered and spanned many developments in their respective fields. Their collaborative success was founded on a shared belief in movement as a profound expressive tool and on their shared interest in translating dance into visual images and vice versa. With the death of their matchmaker Diaghilev, each in a sense channeled him to bring their art into alliance.

As modern ballet and dance evolved and their locus shifted from Europe to the United States, Diaghilev’s models of the impresario and of collaboration gave way to others. In the modern-dance world, the choreographer and the impresario were the same; Martha Graham, for example, forged a decades-long collaboration with the sculptor Isamu Noguchi without an intermediary. Merce Cunningham’s later roster of visual artists was more closely equivalent to that of the Ballets Russes, but both Cunningham and his musical collaborator John Cage rejected the idea of artistic fusion, insisting on the complete autonomy of disciplines, which were, in theory, only brought together on opening night. Today, the prevalence of productions like Four Quartets and Dragon Spring Phoenix Rise may signal a closer return to the Diaghilev model, with its successes and failures dependent on the unifying vision, curatorial instincts, and managerial charm of the nonartist impresario.

So: what do you get when you cross a master choreographer, a luminary painter, and a virtuoso composer with a legendary poet? It depends on “you.”

1Alastair Macaulay, “Hail, Dance, and Farewell to the Critic’s Life,” New York Times, December 28, 2018.

2See, e.g., Nancy D. Hargrove, “T. S. Eliot and the Dance,” Journal of Modern Literature 21, no. 1 (Summer 1997), pp. 61–88.

3Lynn Garafola, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes (Boston: Da Capo Press, 1998), p. 45.

4“Brice Marden and Gideon Lester,” Gagosian Quarterly, June 6, 2018. Available online at https://gagosian.com/quarterly/2018/06/06/brice-marden-four-quartets/ (accessed September 25, 2019).

5Apollinaire Scherr, “Dance is the winner in Dragon Spring Phoenix Rise at The Shed, New York,” Financial Times, July 1 2019.

6Garafola, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, p. 45.

7“Exhibition Guide: Natalia Goncharova,” Tate Modern, 2019. Available online at www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/natalia-goncharova (accessed September 21, 2019).

8Garafola, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, p. 43.

9This was not always Bronislava Nijinska’s style: when working with Jean Cocteau the following year for Le train bleu (The blue train), she found herself in a different dynamic and took a backseat while the poet, fancying himself a choreographer, imposed his will. Cocteau saw choreography as an illustration of a literary libretto rather than its own communicative art form, whereas Nijinska’s practice had cultivated a distancing of movement from traditional narrative.

10Natalia Goncharova, “The Metamorphoses of the Ballet ‘Les Noces,’” Leonardo 12, no. 2 (Spring 1979), pp. 137–43 (part of an article first published in Russian in Russkiy Arkhiv, nos. 20–21, 1932). Translated from a French version of the original text by Mary Chamot.

11Garafola, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, p. 125; Nijinska, “Creation of Les Noces,” n.p., trans. Jean M. Serafetinides and Irina Nijinska, box 19, folder 15, Bronislava Nijinska Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

12See Goncharova, “The Metamorphoses of the Ballet ‘Les Noces.’”

13Vincente García-Márquéz, Massine: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995), p. 20.

14See Hilary Spurling, Matisse the Master: A Life of Henri Matisse; The Conquest of Colour, 1909–1954 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), p. 230.

15Juan Gris, letter to Sergei Diaghilev, n.d., Bibliothèque Nationale, Opéra, Paris, Kochno collection, kochno-39 fund (9-10).

16See Spurling, Matisse the Master, p. 336.

17Léonide Massine, My Life in Ballet (London: Macmillan, 1968), pp. 211–12.