Raymond Foye is a contributing editor to the Brooklyn Rail. His most recent publication is Harry Smith: The Naropa Lectures 1989–1991 (2023). Photo: Amy Grantham

One day I was in a taxi with Graham Nash. As we passed a large self-storage unit in the borough of Queens, he shared a confession that has quietly haunted me ever since. He allowed that one of his erstwhile fantasies in life has been to purchase just such a storage building and then open every single room to examine the contents, thereby coming to know each person through their possessions. A biography in objects might be a good way to describe this essay. Or, how does one use a work of art as an instrument for self-knowledge? This is the question Nash has been asking himself since he came of age in the 1960s.

Nash’s interest in art began in swinging London in the 1960s, where surrealism and psychedelia were transforming the drab postwar cityscape. “I was sitting home in my flat in London, it must have been 1967, and I was in the Hollies. Eric Burdon and I were friends because we both came from the north of England. Eric stopped by with a book under his arm, a monograph on the work of M. C. Escher. I’d actually just taken a tab of acid and it was coming on as I began looking at the images. It was like falling down the rabbit hole in Alice in Wonderland.”

Around the same time, Nash had dinner with Paul McCartney in his home in St Johns Wood, and it was there he saw his first painting by René Magritte, The Listening Room (1952), depicting a large green apple in a room—the inspiration for the Apple records logo. McCartney might well have been speaking for Nash when he told The Guardian in 2008, “What I love about Magritte is he turned the world upside down and inside out in terms of meaning and significance . . . the world is a jungle of crazy interpretations.” The notion that one could live with an object that radiated this kind of power was something Nash had never experienced.

The third crucial factor in shaping Nash’s visual world was his friendship with the Dutch artists Simon Posthuma and Marijke Koger, a design team collectively known as the Fool. Their blend of psychedelia was a continuation of the florid graphics and paisley styles of Fortuny and Liberty of London, turn-of-the-century design houses that were likewise influenced by the colors and patterns of India and the Near East. The Fool designed posters, album covers, and clothing for Cream, the Move, Procol Harum, the Incredible String Band, and the Beatles. Nash hired the Fool to design the Hollies’ 1967 album Evolution, where the band are arrayed in full Fool attire. They also designed some of the earliest psychedelic episodes on film, including the “I am the Walrus” sequence in the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour (1967) and the 1968 cult film Wonderwall with soundtrack by George Harrison.

Nash’s good manners and English civility mask the rapacious predator that lies at the heart of Nash the collector. Whether he is discussing his own photography or his collecting, Nash always refers to it as “the hunt,” and as long as I have known him, he has been hunting images, voraciously. Nash is one of the only two musicians I have ever known who would wake up early in the city where he would be performing that evening and head out to the local museum. (Tony Bennett is the other.) He always has a camera slung over his shoulder, alert to the chance encounter with the unexpected image. He has been a regular at the galleries and auction houses of New York, San Francisco, and London, where he has kept homes over the years. Flea markets and thrift shops are a favorite pastime, and today he often spends his spare hours searching the Internet for artists, or just pursuing a random encounter with a compelling object.

I spent a gray and drizzly afternoon this February with Nash and his wife, the photographer and painter Amy Grantham, in their Lower East Side apartment. These days he lives a life on St. Mark’s Place that is creative and anonymous. That might seem like a strange word to apply to one of the most famous rock musicians of his generation, but Nash has always had the gift of not calling attention to himself. Once in 1991, Nash and I walked the entire length of Golden Gate Park, and not a single person recognized him—and I should add we were walking in the midst of 100,000 fans who had just watched him perform on stage with Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young as part of the Bill Graham memorial concert (which also featured John Fogerty and the Grateful Dead). How is this possible, I kept asking myself? It simply had to do with the way he carried himself. Jack Kerouac once said it is the duty and oath of a writer to observe and not be observed, and this attitude lies at the heart of Nash’s life as a musician and artist.

“I had a poor upbringing in Manchester, England, following the war,” Nash told me. “We had no images on the wall, not a print or a reproduction in a frame, absolutely nothing. I think I’ve always thirsted for images as a result.” Perhaps the mistrust of images can be traced to a strong streak of iconoclasm in British history, such as the sixteenth-century Reformation, in which religious images were destroyed on an unprecedented scale. But there was another reason for the visual scarcity that Nash recalls: following World War II, virtually everything that could be recycled, was—including paper and cardboard. All in all, postwar Manchester was an exceedingly stark environment.

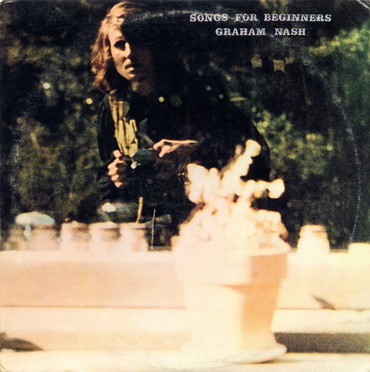

Nash’s collecting did not begin in earnest until after he moved to America and met extraordinary success with Crosby, Stills & Nash. “Suddenly I had almost limitless income.” Nash settled in San Francisco, preferring the music scene there, and shunning the commercialism of Los Angeles. He bought an old Victorian house on Buena Vista Park in the Haight, with beautiful woodwork that he meticulously restored. Suddenly he had walls, in fact many walls, and they needed to be filled. Through a chance encounter with a small newspaper ad, his earliest artistic awakening was rekindled. “I saw by chance an ad in the newspaper from the Vorpal Gallery in San Francisco, they were showing M. C. Escher, so I went by. After years of studying them in books, I’d built up such anticipation of seeing them for real that I bought seven prints the first day. I think in the end I acquired about twenty.”

It was also through a small newspaper ad for Escher that Nash met the private dealer Charles Wehrenberg, who would become a close friend and trusted advisor. Wehrenberg was dealing maps, rare books, and fine-art prints out of the vault of the Bank of America on California and Montgomery streets. “Nash was the first millionaire I dealt with back in the days when people answered their own phone and acquired things to suit their own taste,” Wehrenberg recalled. (The fact that Nash was pursuing his collecting through newspaper want ads is another sign of how the art world has changed.) Nash arrived at the vault with his manager, Elliott Roberts. Both made purchases and both became regular clients.

“Escher’s standing in the art world was tiny, so Nash was foresighted,” Wehrenberg told me. “Escher is easy to criticize, but the good ones are absolutely rare twentieth-century iconic items. I believe his is one of the few artistic careers that will resurface century after century and mean the same thing, because he’s tied into geometry and the logic of thought.” Nash concurs about Escher’s standing: “I think he’s been terribly underestimated, and unfortunately it may have been some of us hippies who were responsible for that, making all those black-light posters of his work.” For years Nash sought and eventually acquired Escher’s masterpiece Metamorphosis III (1968), the artist’s largest work (7 1/2 inches by 22 feet) printed (in an edition of six) from thirty-three woodblocks and hand colored. Nash’s copy remains the only one in private hands.

Nash’s eyes still light up when he recalls his first encounters with Escher’s work in the flesh. “I like to be as close to the flame as I can get, and to handle those Escher prints was a true joy.” Soon, Nash traveled to the Gemeentemuseum in the Hague and spent three days poring over Escher’s work, examining in person nearly the entirety of the Dutch artist’s graphic work. Much of the joy of collecting is furthering one’s education, and Nash is voracious in this regard: “I wanted to understand the entire development, and how he made these discoveries. Collecting is an education, you go down the worm hole. If someone did this wonderful thing, what else did they do?”

The way one thing leads to another is one of the more fascinating aspects of collecting: context, influence, and precedence are integral aspects of art history, and these same elements always seem to play themselves out in a personal collection. Close on the heels of his Escher acquisitions, Nash began collecting German Expressionist prints, drawn to the stark beauty of Erich Heckel and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. This in turn led him to a collection of the wordless novels (in woodcut) of Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward, which in turn led him to the German antifascist propaganda art of John Heartfield. “Communication: that’s what I’m trying to do in my own work, and that’s what I’m drawn to in others,” Nash explains. Does he make any distinction between high and low, popular and fine art? “I’ve tossed this question around in my mind for years. I just like what I like and I go on that. My eye is a strange one, I’m always interested in the surreal moment that disappears in a flash.”

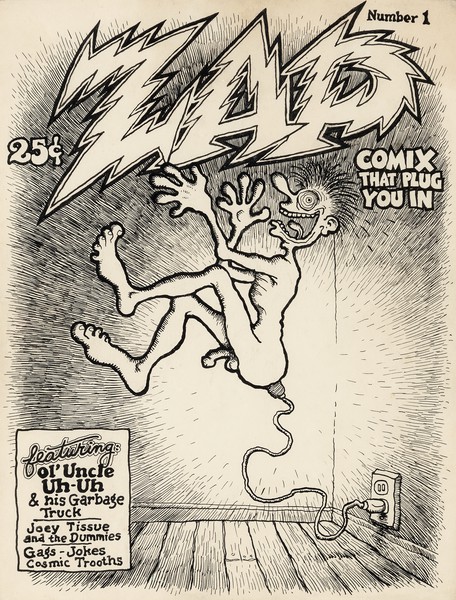

In 1970 Nash began collecting underground comic art of the 1960s. In retrospect this seems like a logical move, especially for a figure at the center of that vortex, but in 1970 there were no serious collectors in this field, and nothing to indicate that the material would ever appreciate to a significant degree. But the art-historical awareness Nash had gleaned from his earlier purchases lent a new perspective, and he purchased R. Crumb’s drawing for the cover of the first issue of Zap Comix for the healthy price of $5,000—a bold move, and one that paid off well in 2017, when it sold at Heritage Auctions of Dallas for $525,800, part of a $1.1 million sale of Nash’s comic art. Why does he sell, I asked? “I think when you have three kids and households in several places, sometimes you need money,” he notes unsentimentally. On further reflection he adds, “When I’ve gotten all the juice out of an object.” It’s a telling remark, because it shows how Nash thinks of these objects as sources of inspiration for his own work.

Nash’s career as a photography collector began in earnest in 1970, when he met the late San Francisco dealer Simon Lowinsky. “Keep in mind that in 1970 serious curators and critics were still debating whether photography could be considered a fine art,” Nash told me. The impetus was seeing Diane Arbus’s classic image Child with a Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C. (1962). It was the first photograph he purchased, paying $4,000. Once again, he felt compelled to acquire the image. “The image gave sharp focus to the madness of war,” Nash later wrote in the introduction to Eye to Eye (2004), a monograph on his own photography. “There’s such hatred in his twisted face. . . . It had a chilling effect on me because I was then deeply involved in trying to raise awareness of the horrors of the war in Vietnam by playing benefits and antiwar rallies. And it was then that I began to realize that I wasn’t seeing the world with enough clarity. Arbus, with her great gift of clear vision, was teaching me how to see. . . . I resolved right there and then to make a greater effort to absorb and react to what I saw, and not just be a passive bystander.”1

Over the next twenty years, Nash amassed a collection of over four hundred photographs that included virtually every major name in the history of the medium. When I asked him to single out a few favorites, in addition to Arbus he named P. H. Emerson and John Herschel from the nineteenth century and Lewis Hine, Weegee, W. Eugene Smith, and Robert Frank from the twentieth. I recall visiting him at his home in Encino, California, in the 1980s, when one could hardly open a cupboard for a tea cup without dozens of photographs tumbling out. Soon Graham Howe was hired as collections-management specialist and the photographs were moved off-site.

In April of 1990, Nash decided he wanted to get in on the ground floor of the digital revolution and opened a fine-art workshop with some of the finest talent Silicon Valley had to offer. “I realized it was going to cost a couple of million to do that, so I decided to sell my entire photo collection.” The auction at Sotheby’s, organized by Wehrenberg, raised $2.4 million, still a record for a single photograph-collection sale. I attended the preview reception with Nash and as we stood in front of the Arbus photograph that had started the whole journey for him, a tall thin man in his late thirties shyly approached. “Do you know who I am?” he asked. Nash looked at him carefully and said no. “I’m the boy in that photograph.” And indeed he was. “You must tell me the story,” Nash pleaded. “It was very simple, I was in Central Park with my mother, playing with my toys, and a young woman approached and asked if she could take my picture. My mother agreed. I happened to be holding that toy hand grenade. All of a sudden I decided to make a funny face and she snapped it. There was nothing sinister happening at all. It was just a nice day in the park.”

In truth, Nash was no stranger to photography. He’d been taking photographs seriously since the age of eleven, as many surviving examples testify, including a haunting portrait of his mother, absorbed in thought, taken unawares. “I had a camera before I had a guitar,” Nash told me. His father, Bill, was an avid amateur photographer. “One day, when I was ten years old, he showed me a piece of magic that changed my life forever. He would develop his negatives in the kitchen, and then nail my blanket to the window in my bedroom, transforming it into a darkroom. I will never forget the moment when I first saw him make a print.”2

The relationship between photography and social justice has always been appealing to Nash, but there is a more personal underlying connection. In the late 1950s, Nash’s father unwittingly purchased a stolen camera from a friend. The police arrived at the house, and rather than reveal the name of his friend—an unforgivable move in the poor working-class city where they lived—his father instead accepted a one-year jail sentence in Manchester’s Strangeways prison, an event Nash memorialized in his 1974 “Prison Song.” “My father was an ordinary, God-fearing, good, hard-working man, and he couldn’t understand why the judicial system was not fair in this particular case. A year in jail for a camera that cost twenty quid is preposterous, but to ruin a man’s life for keeping his sense of honor proved totally confusing to him. He was only thirty-two when he went to jail, but he was ultimately devastated by the experience. I think it broke his heart and very much contributed to his early death at forty-six.”3

Nash has discovered subtle but important parallels between collecting and appreciating art and his own creative life as a songwriter. “When I write a song I may have a very specific idea in mind, and I almost always do, but once you release the song everyone has their own interpretation of it, and in time all those different interpretations actually constitute its meaning. I think all works of art are like that. How I think about art is very similar to how I make music. I love it when someone comes up to me years later and says, You know, I never heard that piano part before. I’m interested in things that unfold, that don’t remain static.”

The chance encounter has always been the basis of Nash’s collecting. “I’m not walking around lusting after objects all day long,” Nash told me. “I try to keep myself open to inspiration. You put yourself in the right mood and the spirit of discovery just happens.” Being on tour became a convenient way for Nash to explore galleries and rare-book shops in locations he might not otherwise visit. Or he could maintain regular contact with favorite dealers, such as Maggs Bros. in London, where, in 1974, he popped in on the afternoon of a sold-out show for ninety thousand fans at Wembley Stadium and made one of his finest acquisitions: a large folio of camera lucida drawings by Sir John Herschel, a prized possession that Nash eventually donated to the Getty Museum.

The mark of any great collector is the combination of education and gut instinct. “Whenever I leave a gallery after seeing something significant, as I’m turning the door handle, there’s always a voice that says, ‘Don’t do it, don’t leave.’ When I hear that voice, I always go back and buy,” Nash told me. I repeated to him a remark Mrs. Vincent Astor once made—that she never regretted anything she ever bought, she only regretted things she didn’t buy. “Easy for her to say,” he said with a smile. And if money were no object today? I asked him. “Off the top of my head, two things I would immediately buy would be the complete twenty-volume photogravure run of Edward S. Curtis’s The North American Indian and the double-elephant folio of John James Audubon’s The Birds of America.”

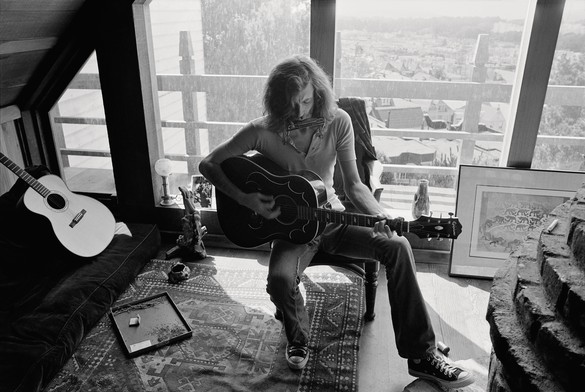

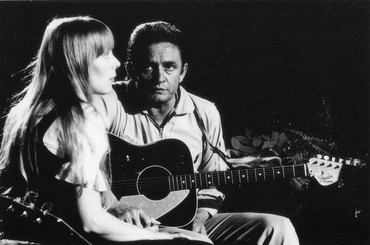

“The life of objects is transmitted through the people who own them,” Nash muses. “Great art never stops working, but when it has satisfied you, it’s time to pass it along to another person.” Nash is unsentimental about parting with artworks once they have satisfied his curiosity. “When I have soaked in what an image or object can teach me, then I can let it go. But not until.” Now seventy-eight, Nash is feeling the need to let go of some of the objects he owns. Last year at Heritage Auctions he sold nineteen vintage guitars, including the Martin D-45 he played at Woodstock, Johnny Cash’s 1934 Martin O-17, and Duane Allman’s circa-1961 Gibson SG, the latter selling for $591,000, making it one of the most expensive guitars ever sold. One guitar that Nash parted with in 1970 recently made $420,000 at Bonham’s: a 1955 Fender Stratocaster he purchased in a Phoenix pawn shop for $300 and gave to Jerry Garcia as a thank you for playing the pedal steel part on “Teach Your Children.” “There was no budget for studio musicians and he played such a memorable part I had to give him something.” Known as the “Alligator” because of a sticker placed on the front by the previous owner, it was Garcia’s touring guitar from 1971 to ’73 and was played on Workingman’s Dead (1970), American Beauty (1970), and Europe ’72.

One thing I’ve always admired about Nash’s collecting is how no object is too small or insignificant to him if it holds some spark of inspiration. For years when he lived in Encino, his favorite pastime was the enormous flea market in the Pasadena Rose Bowl, which often houses five thousand dealers. “I liked it because when I went there I was invisible,” Nash said with a twinkle. “Everyone was just looking straight down, at stuff. You could be Mick Jagger and nobody would know.”

Who are the collectors he currently admires? “In photography? Michael G. Wilson, the producer of James Bond movies. Everything he owns reflects a perfect eye.” Nash ponders the question further. “I’m also deeply impressed with what George Kaiser is creating in Tulsa, with the Woody Guthrie Center, the Bob Dylan archive, and his many other activities. To purchase the entire personal archives of Bob Dylan all in one go showed tremendous foresight. Sure it was expensive, but a year later Bob was awarded the Nobel Prize and the value of the collection must have tripled overnight.” Nash himself is an important collector of Dylan manuscripts. He disappears into the next room and emerges with a manuscript box filled with Dylan’s song lyrics, a college memoir, an unpublished play, and a highly personal reflection on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, among other things. Nash becomes downright morose when I pose the question every great collector gets asked: What’s the one that got away? “That would have to be the Bob Dylan little red spiral-bound composition notebook to Blood on the Tracks. I was out on tour and somehow missed it at auction by one day. Fortunately my friend George Hecksher acquired it, and later donated it to the Morgan Library here in New York.”

I asked Nash to give me a quick tour of the art and objects that surround us in the apartment where we are sitting. “These are pretty much all things that have randomly found their way into my life recently,” he notes. There is a Joan Miró tapestry, a Henry Miller watercolor, a weaving by Edith Zimmer, and a magnificent large Hilla Rebay watercolor. (Rebay is an overlooked abstract painter and the person responsible for commissioning Frank Lloyd Wright to design New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Her work is the latest passion for both Nash and his wife Amy.) “Not all of these are great works of art,” Nash says unapologetically, “but that’s the fun of collecting, to mix it up a little.” There are also many examples of folk and outsider art in the apartment. “I often go to the American Folk Art Museum here in New York. You see the most incredible conceptions outside of what we normally think of as ‘art.’ There’s no theory. They’re just doing it to communicate something.”

For Nash there is a strong but subliminal correspondence between photography and songwriting. Time and again in classic songs like “Our House” and “Marrakesh Express,” scenes are portrayed with a vividness and precision that have been honed from close looking. Story, tableau, light, local color—all are memorably presented. “I don’t see the difference between photography and music. To me it’s all just energy. Being a performing artist you can deliciously change a song each time you perform it.” How do you remain invested in the same material year after year, I ask him. Nash answers with a simplicity and conviction that remind me of his fellow northerner David Hockney, “Because I believe in it. Every time I sing ‘Our House’ I’m back in that living room I shared with Joni Mitchell. And I understand that members of my band sometimes hate it when people sing along, but I thoroughly enjoy it, because they’re invested in that music—it changed their life at some point in some way. And when all you’re trying to do in life is write a memorable tune, why are you getting mad when people sing it?” An attraction to demanding and difficult situations is part of the personality of the collector. “Contemporary art: it’s an endlessly weird thing and it’s not for everybody, but it’s terribly important to allow your mind to escape to places where that kind of vision exists,” Nash muses. “It’s about being forced to come to grips with different views of reality. You have to work at these things. Curiosity is the key.”

A few years ago, Nash was doing a book signing for his autobiography Wild Tales, in his home town of Manchester. After having a book signed, a man slipped him an envelope and said, look at this later. “When I returned to my hotel I opened it, “ Nash said with a smile. “It was my school report card from when I was eleven years old. And the teacher wrote, ‘This boy wants to know everything.’ So I guess I haven’t changed much.”