John Elderfield is chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and was formerly the inaugural Allen R. Adler, Class of 1967, Distinguished Curator and Lecturer at the Princeton University Art Museum. He joined Gagosian in 2012 as a senior curator for special exhibitions.

Those interested in modern art who have been in voluntary isolation with a partner and children since the spring may have wondered: do we have images of what family life was like for the great early modernists? The answer is: at first, yes. As the nineteenth century advanced, it became increasingly common for married bourgeois couples in France to sleep together in double beds, and for much of their private time after marriage to be consumed with children. Greater intimacy between husband and wife, accompanied by closer family relationships generally, meant that paintings abounded of bourgeois parents with their children, including paintings of artists’ families.1

And so it remained through Impressionism. But the sterner modernism that followed was less forgiving of such potentially sentimental subjects, which remained the province of more traditional painters—artists who remained happy to record parents with the children they had begun to call by silly but touching pet names (as they often also did each other), and who posed proudly as families in their overstuffed living rooms. But Henri Matisse or Pablo Picasso?

Actually, three of Matisse’s most important paintings are of his family: The Painter’s Family, The Piano Lesson, and The Music Lesson.2 What follows concentrates on the last two, especially the third. As will become apparent, their implications bear significantly on our present domestic situations, isolated from the viral chaos around us, and not only because both of them depict home schooling.

Two Lessons, Two Styles

These two works were painted in the years 1916–17, but in what order is extremely pertinent to their meanings. Before Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the Museum of Modern Art’s founding director, published his great 1951 monograph on Matisse—the first to establish a plausible chronology of the artist’s work—it was not known which canvas came first. As Barr reported, Pierre Matisse, the artist’s younger son, was “quite certain that the more abstract of the two, The Piano Lesson, is the earlier,” while the artist’s wife, Amélie, remembered that “the more abstract canvas was as usual painted after the more realistic one.”3

Had Madame Matisse been correct, the reputation of The Music Lesson would be akin to that of the first, freer versions of other pairs of the artist’s paintings: though not of the same order as the succeeding, more rigorous composition, it would be seen as an accomplished work. However, as Barr realized, it was Pierre Matisse who was correct. As a result, The Music Lesson has widely been seen as a regression on the artist’s part—a move away from the radical invention of his work of the 1910s, and one leading to the more traditional naturalism that would flourish in the 1920s.

So infuriated about this interpretation was the critic Dominique Fourcade that in 1986 he described its proponents as evidencing “satisfaction in letting the artist die in 1916 with La Leçon de piano . . . even if that meant letting him be reborn from nothingness” in the 1930s, to again work “abstractly and without transition, to the cut-outs at the end of his life.”4 I was not alone in thinking that “letting the artist die” was hyperbole on Fourcade’s part, but it proved no exaggeration: a decade or so later, in 1998, art historian Yve-Alain Bois was writing that with The Music Lesson Matisse “takes leave of himself, and of what I have called his system,” by which Bois meant the conception of painting that the artist had formed a decade earlier and employed through the creation of The Piano Lesson.5 Clearly, if Matisse “takes leave of himself, and . . . his system” in The Music Lesson, then, for Bois, he does at that moment die, at least artistically. To compare these two paintings, then, is unlike comparing any other pair of paintings by Matisse: it is to adjudicate a controversy.

Family Paintings

Let us begin with what the two paintings have in common: size, medium, and subject matter. Both are about eight feet tall by seven feet wide, with The Piano Lesson very slightly the larger of the pair. This makes them the largest paintings Matisse ever made, with the exception of his few imagined compositions: Dance and Music, of 1909–10, and Bathers by a River and The Moroccans, both completed more or less at the same time as The Piano Lesson. Like most of Matisse’s paintings, they were painted in oil on canvas.

To turn to subject matter is to open the pages of a very extensive literature, some of which I myself have written and which interested readers can easily find.6 But at least a summary is needed here, for these two paintings are exceptional both in their particular choice of subject and in their relationship to works on a similar subject. In the latter respect they belong to a long sequence of the artist’s paintings of a privileged interior space, either home or studio or both at the same time. As with some but not all earlier such paintings—the most celebrated example being The Red Studio (1911)—the objects depicted within their interiors have allusive or symbolic qualities, either conventional or original to Matisse. And, like most but not all of the paintings in this subcategory, the manner in which the interior and the objects within it are painted explicitly participates in the shaping of these qualities.

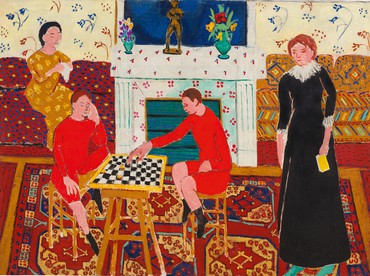

To further reduce the field of comparison, these are, as we have heard, family paintings, preceded in this respect by only The Painter’s Family of 1911.7 To be precise, The Piano Lesson shows only one member of the family—Pierre, the artist’s younger son—while The Music Lesson, just like The Painter’s Family, shows all of its members: Matisse’s eldest child, Marguerite, stands beside Pierre at the piano; his older brother, Jean, sits at the left, smoking while reading; the artist’s wife, Amélie, is outside in the garden; and though Matisse himself goes unseen, he is alluded to through a prominent depiction of his violin, which rests on the piano. It is truly a painting of a painter’s family; and Matisse himself titled it La famille. It was renamed The Music Lesson by Albert C. Barnes, never one to shy from taking such liberties, after it entered his collection (now the collection of the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia) in 1923.8

These paintings, and especially the second, belong to a long tradition of representations of one and usually more members of a family in an explicitly domestic space, and engaged in an activity or activities appropriate to it. The most prominent antecedents are the paintings of, and made for, the comfortable bourgeois households of seventeenth-century Holland. Eugène Fromentin, in his book Les maîtres d’autrefois of 1876, proposed that Dutch art, famous for its domestic interiors, effectively began in 1609, with the beginning of the twelve-year truce in the Eighty Years’ War with Spain.9 Art historian Svetlana Alpers, to whom I owe this observation, points out that wartime paintings of guardrooms and garrisons were the forerunners of these domestic interiors; familial intimacy would have been understood to be the counterpart of martial camaraderie.

By now, alarm bells should be sounding, at least for those who know that the years 1916 and 1917, when Matisse made these two paintings, were very bad years indeed for France in World War I, with more than half a million dead in 1916 and almost as many the following year. Moreover, these works were painted in the living room of Matisse’s home, looking out onto its back garden, where his studio stood.10 The house was in Issy-les-Moulineaux, a suburb of Paris that had transformed itself into a center for the military aviation industry, producing fighter planes; and the household was impoverished by the war, whose guns could actually be heard from the garden on quiet days—guns, and also massive explosions from military mines, both utterly destructive of the French countryside. The loudest of these—on June 7, 1917, during the Battle of Messines—was the product of 600 tons of explosives that blew off the crest along the entire length of the Messines Ridge; it was heard as far away as Dublin.11 The British general who ordered this offensive famously remarked, “We may not make history tomorrow, but we shall certainly change the geography.”12 This was not only a war between nations but also had quickly become a war against nature.

It was around this time that The Music Lesson was painted, in midsummer 1917. That was also when—as Matisse wrote in a letter to his friend the painter Charles Camoin—“Something important has happened in my house: Jean, my eldest, has left to join the regiment at Dijon.”13 What may at first sight appear to be a scene of cultured and contented domestic harmony, then, was about to shattered. This is not only a family painting; it is also a war painting.

Much has been written of the reductive, “abstract” vocabulary of The Piano Lesson as the result of Cubist geometry, on the one hand, and wartime avoidance of luxury, on the other. These factors may indeed have been sources for Matisse as he painted this picture, but a source may or may not be called into play in the finished form of a work of art.14 As I see it, the war as a source is actually called into play more fully in The Music Lesson than in its predecessor, if less obviously. Knowing that Jean Matisse was headed for guardrooms or garrisons aids a martial association that may have been in his father’s mind, but this is present in the painting only for those who know it as well. In what follows, I shall propose that the imaging of this sociable canvas itself invites interpretation as describing a family in a moment of lockdown against mindfulness of anything troublingly external, whereas The Piano Lesson pushes out of our minds all but the moment of twilight grace that it represents.

Rooms with a View

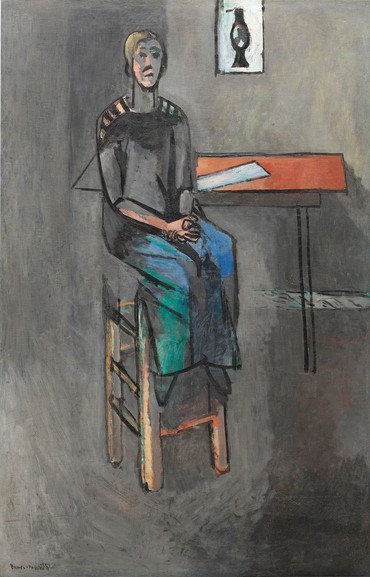

Let us now look at what the two paintings represent, and how they do so. As we have heard, The Piano Lesson shows solely the artist’s younger son, Pierre. He stares out toward us, even while lost in concentration, practicing on a very bourgeois Pleyel piano beside a French window open to the garden. Pierre was sixteen when the picture was painted but looks much younger. Since he and his father were the musicians of the family, he may be thought to function as a surrogate for the painter. In the bottom-left corner of the painting we see Matisse’s Decorative Figure of 1908, arguably the most sexual of his sculptures. Behind Pierre we may think we see a woman seated on a high stool, a severe, supervisory, arguably maternal presence, but this is actually a painting on the wall, Matisse’s Woman on a High Stool (Germaine Raynal) of 1914, transformed to convey these qualities.15 On the rose cloth over the piano, a candle and a metronome recapitulate the opposition of vitality and logic that the sculpture and the painting introduce. Together, they also stress the measuring of time, while the carving around the reversed name of the piano on the music stand flows across time and space, like music, through the grillwork of the window.

Time has stopped at a moment of fading, late-afternoon light in a dimly illuminated interior. An unseen light to the right traverses the scene, striking the boy’s forehead and shadowing a triangle on his far cheek; brightening the salmon-orange curtain and the pale blue-gray of the partly closed right panel of the window; and illuminating a big triangular patch of lawn outside, the only visible feature of the darkened garden. It is the view of the room that matters.

The colors, including that green triangle no more distant than anything else, complement one another in ways that activate the stillness of the scene. The orange converses with the pale blue, and the rose with the green; these are interrupted by a yellow and a black, all of them reconciled by the surrounding soft gray, which they appear to tint. The colors also resist being fully incorporated into the work of objective depiction, largely because they occupy such stark, autonomous shapes. Instead, the strips and shards of color may be imagined as organizing a simulacrum of the spatial experience of such a scene. They alternatively attract and repel each other, as if magnetized, tipping backward and forward in space, even as they shift in position across the plane of the picture. To follow their direction in the means and pace of our attention is to imagine a movement akin to walking through a room and registering the effects of parallax—the apparent displacement of objects in space due to changes in the position of the observer.

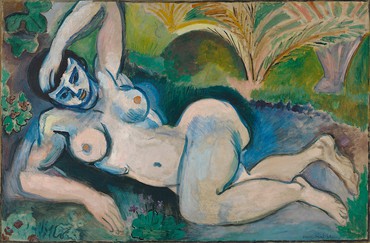

With The Music Lesson, by contrast, everything appears utterly still, and no one looks out of the room; we are excluded. However, we do now see the garden. More precisely, we are shown a view not into the garden but of it, for Matisse has given it the appearance of a painted screen rolled down at the back of the living room, the gray frame around it containing a scene no more real than that of the woman on a high stool in the ocher-framed painting beside it. As such, it may be thought to conceal the reality of what is outside. Prominent beyond the pool is a much enlarged reprise of Matisse’s sculpture Reclining Nude I (Aurora) as re-represented in his Blue Nude: Memory of Biskra (both 1907), the luxuriant backdrop here substituting for the North African setting of the earlier painting, and similarly enhancing the nude’s sensuality.16 The garden erased by twilight in The Piano Lesson may seem a better response to a war that was more ruthlessly and extensively destructive of landscape than any previous. But as the critic Paul Fussell observed of the literature produced during World War I, “If the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”17

Whereas, in making The Piano Lesson, Matisse condensed, eliminating detail, in The Music Lesson he veiled and washed over drawn detail with thinly applied paint. He had been working like this since making his late, dark-and-sculptural Fauve paintings, such as Blue Nude: Memory of Biskra; and he continued to do so in a less sculptural way, and with a lighter palette, even while making more severe, opaque pictures throughout his so-called “experimental period,” of which The Piano Lesson was a summative work. The manner in which The Music Lesson was painted is less a fall from modernist grace, as many critics have characterized it, than a recovery of that late Fauve manner, but with a more intense, indeed almost hallucinatory palette.

Leave-taking

Bois said Matisse took leave of a “system” after painting The Piano Lesson. He characterized that system as “an all-over conception of the canvas” that is “the product of a total democracy on the picture plane, of a dispersion of forces: our gaze is forbidden to focus on any particular area of the picture.”18 I agree that that painting’s successor is a leave-taking painting, but not in that sense: I think Bois’s description also applies to The Music Lesson, and that it is as summative in its own way as its predecessor. The two works encapsulate the momentum of preceding domestic and studio interiors in two different keys, the earlier work drawing together the achievements of the four preceding extraordinary years, the later looking back a decade to see what earlier innovations should be preserved. And it is the later work, with its extraordinarily disjointed composition—of which more in a moment—that shuttles around our gaze the more frenetically.

The putative sweetness and naturalism of The Music Lesson may lull us into believing that it is an undemanding work, but it is as undemanding as, say, Watteau’s paintings of disconnected figures, made two centuries earlier, from which it draws inspiration. Barr perceptively described its style as “descriptive rococo.”19 The artist and critic Amédée Ozenfant invoked another eighteenth-century artist when he observed of the Nice-period paintings that followed The Music Lesson, “This hankering for comfort. . . . When I hear him taking this line à la Fragonard, I have the feeling it is a feint.”20 I myself have the feeling that The Music Lesson is a feint, challenging our preconceptions, at the end of Matisse’s most extremist period of modernism, as to what a modern painting can be.

I therefore find myself disagreeing not only with Bois, who sees The Music Lesson as Matisse’s leave-taking from his time as a modernist painter, but also with Fourcade, who wants to see the artist’s career as “an uninterrupted story.”21 Painting his son Jean’s leave-taking, Matisse does paint a leave-taking of his own, a moving on from what he had achieved over the past few years. He was very clear about this, saying, “If I had continued down the . . . road which I knew so well, I would have ended up as a mannerist.”22 What he ends up as—predicated in The Music Lesson—is an artist determined not to be constrained by the universalizing modernism that he had inherited; hence his fascination with the prerevolutionary eighteenth century.23 This led him to develop from previously unexplored features of his post-Fauve paintings a highly self-conscious, even metapictorial, art of spectacle.

Whereas the modernism of The Piano Lesson is so tautly drawn that we never think of an actual pianist wedged behind the sheet music, the naturalism of The Music Lesson invites us to imagine the members of the family having taken their places where Matisse shows them. If we do imagine that, we must conclude that all of them are oblivious to what is around them, and to each other—except for the intimate couple at the piano, Marguerite protective of her younger brother, Pierre, since the elder one will soon be leaving. Both Jean and Amélie are alone. If we know of his approaching mobilization, we may guess why. Amélie’s isolation—outside the oasislike part of the garden, with its voluptuous sculpture—leaves little to the imagination. Still, whether paired or alone, the family sit in a cramped, busily claustrophobic space. And whether music-making or reading or whatever it is that Madame Matisse is doing—knitting, perhaps—they are not at work; their occupations are pastimes, ways of passing the time. Yet if the The Piano Lesson evokes time measured, The Music Lesson suggests time paused—whether forever or just momentarily is unclear, but Matisse has certainly hit the pause button, with his family at once busily occupied and locked down in place.

Speaking recently of Matisse’s contemporaneous Garden at Issy, art historian T. J. Clark refers to “those pictures—the key pictures, most often, in modernism—where deep inward concentration on means, fierce enclosure in a pictorial world, results in a strength that is not like any kind of pictorial strength we have seen before.”24 The Music Lesson both reflects fierce enclosure and is a picture of one; however, it is a thing of parts and patches less well guarded than The Piano Lesson.

The vivid coloration of The Music Lesson adds an apparitional, somewhat exotic quality to this family tableau, the pink answering the green, the turquoise the brown, and the gray binding the other colors while also separating out the soon-to-be soldier. Barnes compared its large geometric planes of flat color to those of what he called “Oriental art,” an association also applicable to the garden statue and linking The Music Lesson to The Painter’s Family, which was influenced by Persian miniatures.25 As in that earlier painting, the planes, piled one above the other, clash dissonantly, and our unified experience of the picture is to be found in our experience of its discord, not in its formal coherence as a decoratively patterned surface.26 Here, the superimposed flickering filaments of overlaid curvilinear drawing, which camouflage the meeting of the planes as they speak to the garden foliage, increase the sense of a composition poised on the brink of decomposition. As art historian Karen K. Butler acutely observes, “Overall, the strong tension between geometry and arabesque, or order and chaos, creates a mesmerizing subliminal stasis.”27 She adds that while The Music Lesson has been associated with nationalistic wartime critiques of avant-garde art in favor of traditional themes—here, “la bonne famille française”—its formal discord is complemented by its “thematic opposition of tropical and sexual luxuriance with bourgeois order.”28

This is not a regressive work, and there is nothing in it of a retour à l’ordre. Certainly the feint that it has seemed to introduce would become a way of disarming an audience hostile to modernism, but this did not prevent the result from being surreptitiously challenging, often melancholic, and affecting as well as sweetly beautiful. And the sweetness and beauty are obviously as much a challenge to modernist taste as their opposites are to antimodernist ones. In the end, though, what is at once most challenging to accommodate in our familiar picture of Matisse, and most familiar in the art that surrounds us now, is the assertion of the viability of aesthetic spectacle—the false scenic magic of what Charles Baudelaire called “favorite dreams treated with consummate skill and tragic concision.”29

A Man Who Is Not at the Front

This said, I must turn in conclusion to a question that readers may have been asking: even if The Piano Lesson and The Music Lesson are war paintings in the sense that they reflect their creation during wartime—the forces of order and chaos at odds in the family-lockdown canvas especially—they offer no response to the true horrors of the battlefields. In an earlier issue of the Quarterly (Spring 2020) I wrote of how, a half century earlier, the French painter Édouard Manet had faced the question of how to be an activist in his art by vigorously drawing attention to a single indefensible episode of violence, the shocking execution of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, who had been imposed on that country as its ruler through French neocolonialism. What, then, are we to make of Matisse’s silence on the unparalleled slaughter during the years of World War I?

The answer has two parts. The first is that Matisse volunteered for military duty, and even purchased boots in anticipation of serving, but was rejected owing to his age (he was forty-four) and weak heart. He was deeply upset—disappointed and I think ashamed—at not directly serving his country, especially since many of his friends and colleagues did serve, including his close friends Camoin and the painter Albert Marquet, as well as Guillaume Apollinaire and Georges Braque, both of whom were badly wounded and returned as war heroes. Others, however, were successful in escaping service, Robert Delaunay fleeing to Switzerland and Marcel Duchamp to the United States, and we must forget the honor claimed by many of those in the United States who refused the draft during the Vietnam War if we are to understand the dishonor assigned to those who did so in France in 1914. For Matisse, that would have been out of the question.

Second: Matisse spoke of sharing the sense of helplessness and revulsion that so many were feeling over the war, but he did help in practical ways.30 One of the first results of Germany’s invasion of France, for example, was the occupation of Matisse’s northern hometown of Bohain-en-Vermandois, which meant that the artist’s brother, Auguste, and some 400 other townsmen were deported to a German prison camp, leaving his seventy-year-old mother, Anna, alone and in failing health. Matisse sold prints in order to send 100 kilos of bread each week to these prisoners, who were at risk of dying from hunger.31 (Buying each week what works out to be 500 baguettes was no mean task during wartime.)

Yet Matisse clearly felt deeply uncomfortable about the idea of making art that professed to make a difference to what was happening on the battlefields. “Waste no sympathy on the idle conversation of a man who is not at the front,” he wrote to a gallerist, “and besides a man not at the front feels good for nothing.”32 It was impossible for Matisse to conceive of making war posters, as Raoul Dufy did; and paintings of battlefields, such as Félix Vallotton made, were obviously out of the question.33 Speaking for himself, he would write in 1951: “Despite pressure from certain conventional quarters, the war did not influence the subject of paintings, for we were no longer merely painting subjects. For those who could work there was only a restriction of means.”34

Matisse’s reaction to the privations of the war took the form of a self-imposed restriction of means, making do with less in his art as well as in his life. This response, which was ethical as well as pictorial, only increased the intensity of what he achieved. He spurned ostentation in both his personal and his public life, including refusing to draw attention to himself by staging solo exhibitions in Paris while his compatriots were in arms. And even as the Cubists, following Matisse’s own earlier lead, were enriching the color of their works in 1914, he refused ostentation in his art, too—then broke free with The Music Lesson to make his perhaps most underestimated major painting.

1See Anne Martin-Fugier, “Bourgeois Rituals,” in Michelle Perrot, ed., A History of Private Life, vol. 4, From the Fires of Revolution to the Great War, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge, MA, and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1990), pp. 261–337, esp. “From Marriage to Family,” pp. 321–22.

2A fourth, lesser painting, Pianist and Checker Players of 1924, is a reprise of The Painter’s Family. Luxe, calme et volupté of 1904–05 is, obliquely, a family painting, albeit not set in an interior. Illustrations of these and other works mentioned but not illustrated in this essay may be easily found in my Henri Matisse: A Retrospective (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1992). The present text is a substantially revised and expanded version of my essay “Un nouveau départ,” in Cécile Debray, Matisse: Paires et séries, exh. cat. (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2012), pp. 119–24.

3Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Matisse: His Art and His Public (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1951), p. 193.

4Dominique Fourcade, “An Uninterrupted Story,” in Henri Matisse: The Early Years in Nice, 1916–1930, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1986), pp. 47–48.

5Yve-Alain Bois, Matisse and Picasso, exh. cat., Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth (Paris: Flammarion, 1998), pp. 29–30.

6See my essays on The Piano Lesson in Matisse in the Collection of The Museum of Modern Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1978), pp. 114–16, and in Stephanie D’Alessandro and Elderfield, Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913–1917, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), pp. 290–93. The former speaks more of iconography, the latter more of the pictorial process, and both essays contain references to other literature on this painting and The Music Lesson.

7See note 2 above on one later painting, Pianist and Checker Players.

8The finest account of this painting is Karen K. Butler, “The Music Lesson,” in Yve-Alain Bois, ed., Matisse in the Barnes Foundation (Philadelphia: The Barnes Foundation, 2015), 2:214–29.

9See Svetlana Alpers, The Vexations of Art: Velázquez and Others (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005), pp. 86–90. As Alpers points out, pp. 83–84, Matisse’s Still Life after Jan Davidsz. De Heem’s “La Desserte” (1915) belongs to this discussion; on which see my discussion of this painting in Matisse: Radical Invention, pp. 254–59.

10Garden at Issy, a painting made in June–October 1917, around the same time as The Painter’s Family, includes a schematic image of the studio.

11See D’Alessandro, “The Challenge of Painting,” and my “Charting a New Course,” both in Matisse: Radical Invention, respectively pp. 262–69 and 310–19.

12See Peter Barton, Peter Doyle, and Johan Vandewalle, Beneath Flanders Fields: The Tunnellers’ War 1914–1918 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005), pp. 162–83. In Matisse: Radical Invention, p. 319, I relate this explosion to Matisse’s Shaft of Sunlight, also of summer 1917.

13The family had been dreading this event, but Jean had volunteered and was therefore able to choose how he wished to serve. Probably on the basis of what he had seen in Issy, he opted to become an airplane mechanic, and soon left, to everyone’s relief, not for the front lines but to begin his mechanic’s training in Dijon. He was disgusted with the job within a fortnight, but at least he was not fighting in the mud of the trenches. See Matisse, letter to Charles Camoin, n.d. [summer 1917], in Claudine Grammont, ed., Correspondance entre Charles Camoin et Henri Matisse (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des Arts, 1997), p. 105.

14See Christopher Ricks, Allusion to the Poets (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 3–4.

15Woman on a High Stool is a portrait not of Mme. Matisse but of Germaine Raynal, the then-nineteen-year-old wife of the critic Maurice Raynal, who was closely allied with the Cubists. Here, though, she fulfills a role in the painting, and by extension in the Matisse household, akin to that of the chilly, dignified Mme. Bellelli in Edgar Degas’s Bellelli Family of c. 1860, a figure who, in Martin-Fugier’s description, “accurately portrays the role of the bourgeois mother.” “Bourgeois Rituals,” p. 269.

16Matisse’s The Moroccans, another painting of a North African motif, conceived in 1912, was finally completed in November 1916, between the two family paintings and at a time of increasing concern for African soldiers involved in the war and visible on the streets of Paris.

17Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975), 231. Fussell continues, “Since war takes place outdoors and always within nature, its symbolic status is that of the ultimate antipastoral.” Matisse’s final two (of six) sessions of work on his Bathers by a River (conceived 1909), which took place in 1916 and 1917, transformed what had begun as a pastoral composition into what is commonly understood to be an antipastoral one. The Piano Lesson and The Music Lesson were among the paintings he made when taking a break from making the critical changes on that enormous canvas. Its six-part development is charted in Matisse: Radical Invention, pp. 88–91, 104–07, 152–57, 174–77, 304–09, 346–49.

18Bois, Matisse and Picasso, pp. 29–30.

19Barr, Matisse: His Art and His Public, p. 194.

20Amédée Ozenfant, Mémoires, 1886–1962 (Paris: Segher, 1968), p. 215; quoted here from Pierre Schneider, Matisse (New York: Rizzoli, 1984), p. 506. I have discussed this statement previously in Henri Matisse: A Retrospective, pp. 37–41.

21Fourcade, “An Uninterrupted Story.”

22Matisse, quoted in Ragnar Hoppe, “På visit hos Matisse,” in Städer och Konstnärer, resebrev och essäer om Konst (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1931), 196, recording a visit to Matisse in 1919. Trans. in Jack Flam, ed., Matisse on Art (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), p. 75.

23Edward Said has relevant things to say here in “Return to the Eighteenth Century,” in his On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (New York: Pantheon, 2006), pp. 25–47.

24T. J. Clark’s lecture “Attention to What? Matisse’s Garden at Issy, 1917,” which speaks of Garden of Issy as reflecting its wartime creation, was delivered as part of the Glasgow International, March 2020.

25Albert C. Barnes, The Art in Painting (Merion, PA: The Barnes Foundation Press, 1925), 360. Quoted here from Butler, “The Music Lesson,” p. 222.

26I draw here on my remarks on The Painter’s Family in Henri Matisse: A Retrospective, p. 63.

27Butler, “The Music Lesson,” p. 219.

28Ibid., 227 n. 7, questioning the interpretation in Kenneth E. Silver, Esprit de corps: The Art of the Parisian Avant-Garde and the First World War, 1914–1925 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), pp. 200–203.

29I observed earlier that the garden in The Music Lesson resembles a painted screen rolled down at the back of the living room; in the passage quoted here, Charles Baudelaire is discussing his admiration for backdrop paintings on the stage. He concludes, “These things, so completely false, are for that very reason much closer to the truth.” Baudelaire, “Salon of 1859,” discussed in and here quoted from Walter Benjamin, “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire,” in his Illuminations, ed. and intro. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken, 1968), p. 193.

30See Matisse, letter to René Jean, October 1, 1915, quoted in my entry on Still Life after Jan Davidsz. De Heem’s “La Desserte”, in Matisse: Radical Invention, p. 255.

31See D’Alessandro’s entry on For the Civil Prisoners of Bohain-en Vermandois and her essay “The Challenge of Painting,” both in Matisse: Radical Invention, respectively p. 249, pp. 264–65.

32Matisse, letter to Léonce Rosenberg, June 1, 1916, quoted in D’Alessandro, “The Challenge of Painting,” p. 263.

33On the activities of French artists during the war, see Silver, Esprit de corps, and Richard Cork, A Bitter Truth: Avant-Garde Art and the Great War, exh. cat. (London: Barbican Art Gallery, and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

34Matisse, in E. Tériade, “Matisse Speaks,” Art News Annual 21 (1952): pp. 40–71, quoted here from Flam, ed., Matisse on Art, p. 205.

Artworks by Henri Matisse © 2020 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York