Taylor Aldridge is the visual-arts curator and program manager at the California African American Museum (CAAM), Los Angeles. She has organized exhibitions with the Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit Artist Market, Cranbrook Art Museum, and the Luminary (Saint Louis). In 2015, along with art critic Jessica Lynne, she cofounded ARTS.BLACK. Photo: Paper Monday

In the Black American tradition, inheritance is not historically tied to economic wealth, but to memory, culture, rituals, and wisdom—a different kind of prosperity that is engendered out of love and respect. This type of wealth is cultivated through generations by the living, who are responsible for never forgetting those who have passed on. In return, the living inherit these elusive gifts, helping them to better navigate this thing called life. I consider the ways in which Alice Walker sought out Zora Neale Hurston after her death, reviving her from posthumous obscurity.1 Walker did so by claiming to be a progeny of Hurston, even if that wasn’t entirely true. Elders are sometimes chosen, and through acts of deference we become worthy of their legacy. When I think about Walker’s reclamation and subsequent revival of Hurston’s life and work, I think often about the way in which my generation of art scholars might do the same in the field of contemporary art.

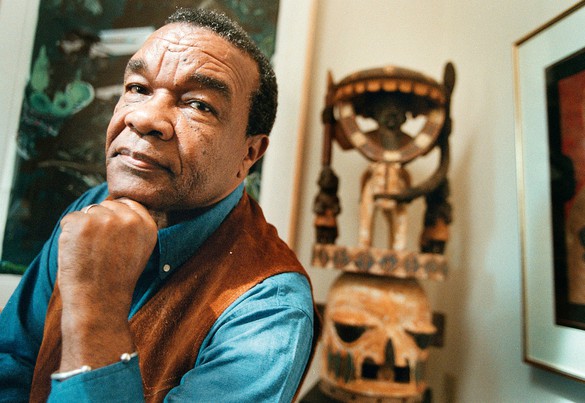

Last year, we lost one of the greatest pioneering scholars of modern Black art: David Driskell. Since his passing, I have been thinking about the ways in which we might institute posthumous care. So few of us are deserving in carrying the torch on the path he lit for us decades ago. Similarly, Linda Goode Bryant, Okwui Enwezor, Suzanne Jackson, Kellie Jones, Samella Lewis, Howardena Pindell, and countless others have dreamed worlds for us where we can be our most capacious selves. Some live, some have passed on; we will forever be indebted to these leaders.

Driskell knew deference well. Having grown up in Eatonton, Georgia, raised by his mother, a housewife, and his father, a Methodist preacher, Driskell described his childhood as an “encouraging atmosphere” in which he was exposed to a community of leaders who often held him accountable in his studies.2 This encouragement would propel him into undergraduate studies at Howard University, Washington, DC, in 1949. He did not take his first art class at Howard until 1952; he was a history major, with no intention of studying art history specifically, until a professor told him in an art class one day that “you don’t belong [in the history department]; you belong here [in the arts].”3 This declarative statement came from pioneering art historian James A. Porter, a professor at Howard and the author of the seminal textbook Modern Negro Art (1943). Driskell would later describe Porter’s majestic teaching style: “He would walk around in the classroom and never use the book [Modern Negro Art] and cite what was in the book. And I was so impressed with him and wanted to do that and be like him. … I would stand up and start reciting what was in the book and pretending that I was Professor Porter.”4 Sometimes, to begin to imagine alternative and ambitious routes in life for ourselves, we have to locate our aspirational selves in others.

Driskell became a bit of a darling at Howard, praised often by professors Porter, James V. Herring, Lois Mailou Jones, and Alain Locke. During his undergraduate studies he developed an art practice, exhibited his work throughout the United States, and curated exhibitions at the university’s Gallery of Art. Driskell was primed to be a major figure in late-twentieth-century American art; his mentors at Howard poured into him all the wealth of knowledge they had amassed in their careers. But his final and most significant encouragement came when, before he graduated, Porter advised that he not only focus on painting but consider becoming a scholar to “help define the field and keep the tradition going.”5 Porter explicitly passed the torch of African American art discourse to Driskell, and even in his youthful outlook, Driskell accepted the challenge with filial pride.

Driskell insisted that Black art is American art.

It is significant that Porter had a distinct belief about how art by African American artists should be treated, believing that it should not be segregated and “belonged within the mainstream canon of American art,” according to scholar Julia L. McGee.6 This same ethos would be the guiding mission of Driskell’s career and of the landmark show Two Centuries of Black American Art, which he curated at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1976. Driskell insisted that Black art is American art, and by paradoxically dissecting and platforming the long-marginalized and quieted legacy of art contributions made by Black artists in America, his exhibition would help insert such histories within the previously ahistorical narrative of American art in the second half of the twentieth century. Two Centuries of Black American Art came well after Driskell had established himself as a scholar and curator, having taught and developed art departments at Talladega College and at Howard and Fisk universities. He had contributed to several exhibition catalogues and stood firmly in his beliefs about how Black art throughout American history should be appreciated. The endeavor was a long stroke of revision and editing of the field of art.

This ambitious show included over 200 objects, dating from 1750 to 1950. It won large audiences and wide press coverage and traveled to the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. But it received mixed reviews for its explicit intention of codifying works through ethnic experience. Driskell would later insist, “I did it … so people would know that this is not a level playing field and that somebody has to point this out and have the courage to show why it should be done my way.”7 With all the accolades Driskell received—more than a dozen honorary degrees, a National Humanities Medal from President Bill Clinton in 2000, the title of distinguished professor emeritus at the University of Maryland—his courage always remained grounded in a sense of humanity and accessibility to others. His conviction and generosity would spill over to foster the careers of other scholars who came after him in the field. Pamela Newkirk, professor at New York University and author of a forthcoming biography of Driskell, recounts that in the recent years before his passing, he continued to provide space and time for friends and mentees in the field, often writing letters of recommendation and advocating for the work of budding scholars.8 Driskell had assumed the role of mentor—the role of Herring, Jones, Locke, and Porter—and committed to it with grace and dedication.

While earning his MFA at the Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, in the 1960s, Driskell was indelibly marked by the influence of professor Nell Sonneman, who focused on the importance of spirituality and beauty in artmaking. At the height of racial terror and the fight for civil rights in the United States, Driskell found refuge in the allure of form and the metaphorical possibilities of nature. After a summer studying in Skowhegan, Maine, he returned to Catholic University and wrote his thesis on the evergreen tree as a symbol of eternity.9 I like to think that Driskell was foreshadowing his own stature in the art field, writ large through this particular scholarship: rendering himself as a quiet-natured yet towering figure, looming large in the canon for centuries to come.

1See Alice Walker, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” Ms., March 1975. Available online at https://www.allisonbolah.com/site_resources/reading_list/Walker_In_Search_of_Zora.pdf (accessed March 21, 2021).

2David Driskell, in Cynthia Mills, “Oral history interview with David Driskell,” March–April 2006, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Available online at https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-david-driskell-15943#transcript (accessed March 21, 2021).

3Ibid.

4Ibid.

5Ibid.

6Julia McGee, David C. Driskell: Artist and Scholar (Petaluma, CA: Pomegranate Communications, 2006), p. 16.

7Driskell, in Mills, “Oral history interview with David Driskell.”

8Pamela Newkirk, “How Late Curator and Artist David C. Driskell Changed Art History Forever,” Artnews, April 10, 2020. Available online at https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/pamela-newkirk-david-driskell-rememberance-1202683648/ (accessed March 21, 2021).

9McGee, David C. Driskell, p. 49.