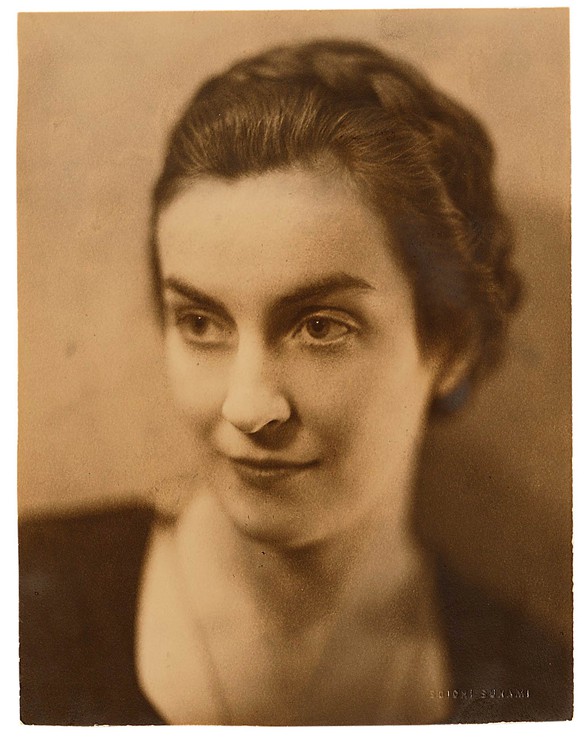

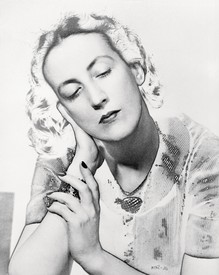

Wendy Jeffers is completing a biography of the legendary curator Dorothy Miller. She is past chair of the board of trustees of the Archives of American Art.

“These are the sixteen artists most likely slated for oblivion,” sniffed John Canaday, chief art critic for the New York Times, when Dorothy Miller’s exhibition Sixteen Americans opened at the Museum of Modern Art in 1959. Sixteen Americans introduced the work of Jay DeFeo, Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Louise Nevelson, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, Jack Youngerman, and nine others to a museum audience for the first time. When the show opened, Miller had been pioneering the Americans, a series of groundbreaking exhibitions of contemporary art, for over fifteen years. Her exhibitions were newsworthy because no other curator was doing anything like them. The art historian Robert Rosenblum recalled that the series as a whole “had something of the excitement and glamour, the sense of near-divine judgment we might associate with the Oscar and Pulitzer Prizes. There was endless speculation and gossip beforehand about who was in and who was out, and no less controversy afterwards. . . . [Miller] wrote a major history of those incredible years . . . through the most uncharted and thrilling seas the New York art world has ever known.”1 Reviewing Sixteen Americans in the Saturday Review, Katherine Kuh observed, “This show does not pretend to reflect the present as much as foretell the immediate future.”2 Conversely, Emily Genauer dismissed the show in the New York Herald Tribune with the statement that “Frank Stella is unspeakably boring.”3 After the opening, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., MoMA’s founding director, turned to Miller and said, “Congratulations, Dorothy, you’ve done it again, they all hate it!”4 By 1959, however, Miller had become inured to vitriolic criticism.

Dorothy Canning Miller was the first professionally trained curator hired at the Museum of Modern Art, which she joined in 1934, joining in a staff of thirteen (including a receptionist, a switchboard operator, and a man at the front desk who sold postcards and catalogues). In a field dominated by men, Miller’s rapid evolution into America’s first museum curator of contemporary art was not without setbacks, but she persevered: at MoMA she became the pivotal curator of her generation, championing American artists at a time when few curators were paying any attention to them. Opening in New York and then touring across the country, the Americans series introduced several generations of American artists to a skeptical and often openly hostile audience. In 1958, Miller organized The New American Painting, an exhibition of seventeen artists and eighty-one works of art that toured European capitals for a year.

Miller’s ability to identify new talent was simply unparalleled. She counted many artists as friends, and they in turn introduced her to the cutting-edge work of their colleagues. Her calendars were littered with appointments for studio visits, and if the artists lived and worked out of town, they would send their work to the museum for her to see. Her practice was not New York–centric: “It seemed desirable to include a larger proportion of newcomers to the New York scene,” she wrote in the foreword to the Sixteen Americans catalogue. “Six of the sixteen have not yet had one-man shows in New York and several others have shown but once or have held shows not truly pertinent to their present work.”5 Highlighting the diversity she was seeing in the galleries and studios, Miller developed an exhibition layout for the Americans shows that became known as the “Dorothy Miller format,” a carefully choreographed sequence in which each artist had separate galleries, often demarcated by walls painted different colors. Describing the result as “a series of small one-man shows within the framework of a large exhibition,”6 she believed that this gave a “broader and more effective view of individual achievement.”7

Artists look at art differently from the general public: first and foremost, of course, they see it through the filter of their own work, but they also look at art as a process rather than a product. They may occasionally look with a jaundiced eye, eager to steal ideas or spot trends, but they still look for the underlying structure of a work, be it physical or philosophical, particularly when it is a radical departure from anything they have seen before. When artists talked with Miller, they talked about the process of making art. As a result, she understood their work at a foundational level, well in advance of the critics and pundits.

As a curator, however, Miller had other criteria to consider: was an artwork a lasting contribution? Was it original? Did it change the way we look at things? Had the artist’s work matured enough to show in the white-hot spotlight of the Museum of Modern Art? Miller often tracked an artist’s progress over many years before showing it, if the work interested her, and though she couldn’t show all the artists she was tracking, she often helped them to find dealers and collectors, as well as writing countless recommendations for grant applications. Artists as diverse as James Lee Byars, Forrest Bess, and Cy Twombly benefited from her advice and support, although she never exhibited their work. When she declined to recommend an artist, her response was gracious and supportive: “It would be better if you didn’t use my name as a reference. I do hope you will understand my reasons for saying this, knowing that I wish you all success. There are several other painters whom I have promised to recommend and about whose work I feel I can speak with greater personal enthusiasm.”8 Miller rarely used the word “important”—a commercial rather than an aesthetic description—but I often heard her use terms such as “significant” and “emotionally compelling.” Because she was in the trenches—alongside the artists—she didn’t follow the nascent art market, nor was that necessary except when making recommendations for museum purchases. In 1948, for example, Miller encouraged MoMA to buy a black-and-white painting from Willem de Kooning’s first one-person exhibition, at the Charles Egan Gallery; it was the only work he sold.

I was still in graduate school when I met Miller, who had just crossed MoMA’s threshold of mandatory retirement at the age of sixty-five. She planned to take on five or six major projects and invited me to work alongside her part-time, which I did for almost twenty years. Slowly, she began to tell me stories about her life and career.

Miller’s first Americans show was in 1942, and one of the artists she included in it was Morris Graves, whom she had discovered on the West Coast. Graves was very shy, and reluctant to exhibit, and Miller remembered that he threw a group of his works on paper into the back of his pickup truck in order to meet her in the basement of the Seattle Art Museum. MoMA bought nine of his gouaches, Miller herself bought two, and during the show she sold more than thirty-five of his works to various trustees and staff members at prices she had established with Graves, who did not yet have a dealer. When he received the check for his sales, he was elated and wrote her that now that he was able to pay off all his debts, he could walk through town with his head held high. Fifty years later, Graves visited Miller at her apartment in New York and after carefully studying her collection, he asked her, “Who is going to tell the story of how you helped so many artists?” Dorothy, who was by that time in her mid-nineties, leaned toward him and in a loud stage whisper said, “Wendy will tell them.”

On a curator’s modest salary and buying on installment, Miller assembled a remarkable collection of contemporary paintings, drawings, sculpture, prints, and photographs, as well as Native American and folk art. When she died, in 2003, more than half of her collection was donated to museums and the remainder was sold at auction for $13,000,000. Several pieces broke records primarily because she had selected and owned them. She belonged to the first generation of collectors of American folk art: able to purchase these works at very modest prices in the 1930s and ’40s, she collected dozens of weathervanes, paintings, theorem pictures, and chalkware figures. When Graves visited her apartment, he was enchanted with her folk art collection, particularly a watercolor of a watermelon. He turned to me and said, “I could sign this one.” He walked past the works by Nevelson, Stuart Davis, and Franz Kline hanging in her apartment, but he stopped and looked carefully at the work of Loren MacIver.

Miller’s shows often plunged her into controversy, occasionally to the point of threatening her position. Fourteen Americans, which opened at MoMA in September 1946, included works by Arshile Gorky, David Hare, Robert Motherwell, Isamu Noguchi, and Mark Tobey, but also by lesser-known artists such as MacIver, David Aronson, Ben Culwell, Alton Pickens, and Honoré Sharrer. (Sharrer and Pickens had never had solo shows and Culwell had exhibited only in his native Texas.) Miller considered including Jackson Pollock but decided that his work had not matured sufficiently. The exhibition won generally good reviews; Robert Coates wrote in The New Yorker, for example, that he was particularly “impressed . . . with the work of Ben L. Culwell, a young Texan . . . [his work] combines Abstraction and Expressionism in a way that produces a maximum amount of emotional intensity.”9 The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (SSV), however, viewed Culwell’s work quite differently, notifying the museum that it objected to the reproduction of his Figment of Erotic Torture in the exhibition’s catalogue. The publication had been “brought to their attention by way of a complaint as to its indecency.”10 MoMA was forced to reprint the catalogue without the offending image.

Founded in 1873 by Anthony Comstock to protect the American public from pornography, the SSV wielded considerable legal and financial power; its dubious accomplishments included preventing birth control literature from being distributed through the mail and barring the publication and distribution in the United States of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1920), D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928), and novels by Oscar Wilde and Frank Harris. MoMA’s trustees were upset—Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, one of the museum’s founding trustees, wrote the staff, “the inclusion of ‘Erotica’ [sic] . . . has greatly shaken my faith in the judgment, taste and integrity of standard of the staff of the Museum”—and Miller almost lost her job.11 But her colleagues rallied: René d’Harnoncourt, then the museum’s director of the curatorial departments and later its director overall, wrote Mrs. Rockefeller that “the subject matter and its treatment has many classical precedents and can be found in works by Matthias Gruenewald, Hieronymus Bosch, Martin Schongauer and other old masters in the great museums of the world.” He added that going forward, a new committee would review works to be included in temporary exhibitions “with a view to their effect on the public.”12 Mrs. Rockefeller died shortly thereafter, the SSV shut down in 1950, and the museum’s review committee, which was rarely mobilized, quietly folded at the same time. Miller, however, continued to court criticism, but it now came from audiences and critics.

That a woman raised in an austere Victorian environment, one that emphasized modesty and service, became the world’s leading curator of contemporary American art is an enigma worth examining. All her adult life, Miller lived in Greenwich Village, surrounded by younger friends and colleagues, and her youthful curiosity never left her. Her long career spanned several generations of artists, which is rare; many curators have difficulty staying current by embracing new stylistic trends—in a phenomenon called “period eye,” they tend to focus on only one art-historical generation, and if they are curators of contemporary art, that generation is often their own. Born in 1904, Miller belonged to the generation of the Abstract Expressionists—de Kooning was born the same year—but after she showed their work, she began to look at the work of younger artists. A number of the older artists had difficulty with the newer work she showed and expressed their disdain.

While she often conferred with trusted colleagues, Miller knew what she liked and why she liked it. Writing to Smith College to recommend MacIver for an honorary degree, she observed, “For some fifteen years, from the mid-thirties until about 1950, Loren MacIver was, in my opinion the best American woman painter, though that distinction went at the time to a much older and more famous lady [Georgia O’Keeffe]. It was only within the decade of the fifties and the movement known all over the world as abstract expressionism that other women painters of real quality developed.”13 Miller continued to look at young artists until she was too old to navigate the long flights of steps leading up to the SoHo lofts; she continued to visit galleries well into her nineties. She avoided overidentifying with any generation in part because she chose not to write interpretive essays for her Americans catalogues, instead asking the artists to write statements about their work, a practice that allowed her to stay nimble as she studied the diverse artistic trends that were occurring simultaneously in a rapidly changing field. Characteristically, when asked about her incredible track record of discovering new talent, she demurred and said, “I was lucky to be alive—it was the artists who were making the incredible contributions.”14

1Robert Rosenblum, exh. brochure for A Curator’s Choice: A Tribute to Dorothy C. Miller, Rosa Esman Gallery, New York, 1982.

2Katherine Kuh, “Fine Arts: The Contemporary Canvas of the American Canvas,” Saturday Review, January 23, 1960, p. 40.

3Emily Genauer, New York Herald Tribune, December 16, 1959.

4Alfred H. Barr, Jr., as reported to the author by Dorothy C. Miller.

5Dorothy C. Miller, “Foreword and Acknowledgment,” Sixteen Americans, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1959), p. 6.

6Ibid.

7Miller, Foreword, in Fifteen Americans, exh. cat. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1952), p. 5.

8Miller, letter to Walter Kamys, 1958. Department of Painting and Sculpture Artist Records 1.143, Museum of Modern Art Archives.

9Robert Coates, “The Art Galleries: All-American,” The New Yorker, September 21, 1946.

10New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, letter to the Museum of Modern Art, March 5, 1947. Rockefeller Family Archives, NAR III 4.L Box 137, Folder 1345, “Fourteen Americans.”

11Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, letter to Alfred H. Barr, Jr., John Abbott, René d’Harnoncourt, and Monroe Wheeler, February 21, 1947. Nelson Rockefeller papers, Rockefeller Archives, RG III.4.L.

12René d’Harnoncourt, letter to Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, February 24, 1947. Nelson Rockefeller papers, Rockefeller Archives, RG III.4.L.

13Miller, letter to Gwendolyn Carter, Committee on Honorary Degrees, Smith College, December 23, 1960. Dorothy Miller papers, MoMA Archives, III.3.a.i Museum matters correspondence.

14Miller, conversation with the author.