Charles Stuckey is a widely published independent scholar who has served as curator in major US museums including the Art Institute of Chicago, helping organize highly acclaimed retrospectives for Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet, and others. He is currently head of research for the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of the paintings of Yves Tanguy.

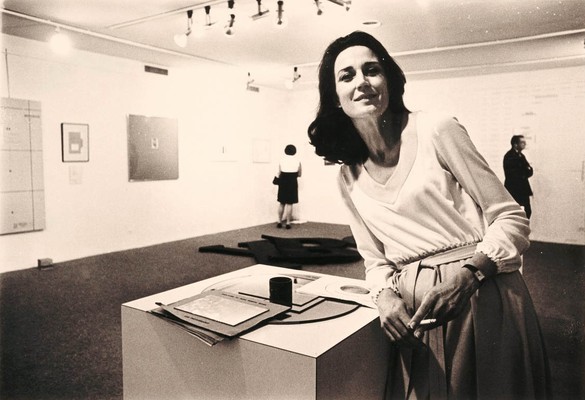

No one in the postwar art world was more trusted and beloved than Virginia Dwan, who died on September 5 at the age of ninety. One of the foremost art philanthropists of her generation, she always engaged directly with the artists she supported to share in the spiritual peace or exhilaration of their visions. An artist herself from time to time, she took special satisfaction in Dwan Light Sanctuary, her creation at United World College in Montezuma, New Mexico. Opened in 1996 with various ecumenical ceremonies, this meditation sanctuary had its origin in a dream about the spiritual significance of the number twelve (astrological signs, months, etc.), which she associated with the experience of visiting a pueblo kiva. She took me there in 2011 to experience the meditative calm. Large prisms, designed in dialogue with Virginia by the artist Charles Ross, refract the light entering large windows so that spectral colors slowly sweep across the walls and floors. After exhibiting at the famous Dwan Gallery in Manhattan, in the early 1970s Ross began construction of Star Axis, an observatory structure far outside Santa Fe, finally completed this year. Virginia also invited the architect Laban Wingert to collaborate on the realization of her concept. Bringing artists together, interactively when possible, with herself at the table was her modus operandi.

Enabled by an inheritance and the recent expansion of transcontinental jet service, Virginia, smart, gracious, idealistic, adventurous, and good looking, started to collect postwar art in 1959, at the age of twenty-eight, along with her husband, Philippe Kondratief. She simultaneously opened a Los Angeles gallery to bring works by prominent New York– and Paris-based artists to a West Coast audience. Eager to expand her own consciousness in the company of visionary personalities, while at the same time reducing shipping costs and hassles, Virginia invited faraway artists to visit Los Angeles with their partners, providing beachside accommodations and studio space. Once there she introduced them to local artists, such as Ed Kienholz, and to collectors and curators, some of them friends from 1950s college art classes. Word soon got out that spending a few weeks in Los Angeles to do a show with Virginia was creatively invigorating. As a gallerist, she collaborated energetically with the artists, sponsoring and publicizing a nonstop program of exhibitions, screenings, lectures, and performances, and often joined forces with her fellow LA gallerists. Lifelong dialogues with John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, Niki de Saint-Phalle, and Jean Tinguely resulted from the hospitality she provided while coordinating something like an arts festival in March 1962, when the Merce Cunningham dance company came to town. She offered artists contracts with monthly stipends as advances against future acquisitions, consequently stockpiling unsold works. Starting in the 1980s she donated hundreds of these to museums, culminating with her transformative donation to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, in 2016.

Success followed success. But as her marriage dissolved, in 1964 Virginia took a sabbatical from her gallery business to live in Manhattan, her primary home for the rest of her life. She quickly joined the patrons of the downtown artists’ cooperative Park Place. In order to accommodate an especially large sculpture by Mark di Suvero (one of the Park Place artists) at her pristine Los Angeles gallery in September 1965, she was obliged to cut a hole in the ceiling, a gesture that exemplified her commitment to doing no matter what on behalf of art while at the same time foretelling her growing awareness of the limitations of a traditional gallery for art free from commercial considerations.

Artists were crazy about her. She delighted in a postcard from Ad Reinhardt dated May 12, 1965: “I want you to show your affection for me more in public, what are people going to think otherwise . . . I want to talk to you of private matters, I want your advice about my career, I want you to be nicer to me, I want to see you.” Of course, like the other established artists whose work Virginia exhibited in Los Angeles, Reinhardt was already under contract with a New York gallery. Undaunted, Virginia welcomed the opportunity to assemble her own team of artists, whose works all partook of what she described in a lecture of 2004, “Selling Silence,” as a “quiet” look, with an emphasis on sublimity, conceptual rationality, energy, essence, and/or wholeness. When I first interviewed her at length, in 1984, we sat in her living room, where her Abyssinian cat danced across the rungs of a modular white wall construction by Sol LeWitt, who brought her attention to other eligible artists, including Carl Andre and Robert Smithson. Sometimes at her apartment in company with Reinhardt, more often at the bar Max’s Kansas City, these artists discussed the scope and contents of a special show to be presented in October 1966, entitled 10 (because the artists could not agree on another title), that would define this new quiet look, generally now called Minimalism. No less a perfectionist than Agnes Martin, one of the exhibiting artists, wrote to Virginia that this show was “the only one about which I have always felt happy and satisfied—a show that was just right.”

Virginia told me that when Smithson encouraged her to read The Annotated Alice, a scholarly edition of Lewis Carroll, she identified with Alice asking the Cheshire Cat which path to take. The artist Bill Anastasi told me how thrilled the gallery artists were every Christmas when Virginia gave out gift certificates to Rizzoli’s to splurge on books and recordings. She encouraged them to make field trips and expand their minds, sharing Reinhardt’s passion for travel to open the imagination to art as a universal experience rather than a tradition related to a particular time and place. When possible, she accompanied them, to participate in and help document their discoveries.

It was with Smithson most of all that she came to understand the limitations of gallery space, exhibiting physical samples, photographs, and film of his Land art works in the gallery as documentary tokens of large ideas emphatically at a remove from it. In October 1968, after conceptually sympathetic artists, including Walter De Maria and Michael Heizer, had joined the gallery, she presented Earth Works, a group exhibition to investigate and encourage this new direction. An application to participate in a Swiss art fair in 1969 summarized the mission: “We have found it increasingly difficult to operate within the traditional confines of the gallery format and our exhibitions have been, for the most part, documentations of activities and realizations of large projects which have taken place elsewhere, usually in an outdoor setting.”

As if inspired by her own program, Virginia closed the gallery in 1972, without interrupting her support for special projects: Heizer’s City in remote Nevada, only recently completed fifty years later; De Maria’s first, trial version of The Lightning Field, a ten-pole installation in Arizona; and Ross’s Star Axis. She had always run the gallery at a loss and was facing tax penalties. As she decided to leave the gallery world, Virginia was aware that the German dealer Heinrich Friedrich, whose Munich gallery had presented some Dwan artists in Europe, now intended to open a space in the SoHo neighborhood, where contemporary-art galleries were moving into larger spaces. Indeed Friedrich’s role in creating the Dia Art Foundation to support vast artist projects can be understood as an extension of Virginia’s ideas about art philanthropy.

It was when Virginia agreed to be interviewed for the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art that I first met her. In 2010 she asked me to undertake a follow-up interview. It has never been my pleasure to discuss art with anyone more high-minded and farsighted. Surely any account of the visionary artists she supported will be inadequate if it overlooks how crucial Virginia was in so many ways to their success.