William Breeze, also called Hymenaeus Beta as world head of the Ordo Templi Orientis, is an American writer and publisher on Magick and philosophy.

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

—Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “Kubla Khan: Or, A Vision in a Dream,” 1797

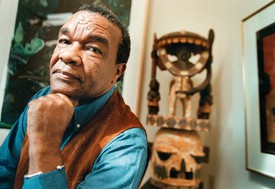

In Memoriam Dr. Kenneth Anger (1927–2023), Frater Focus XI° O.T.O.

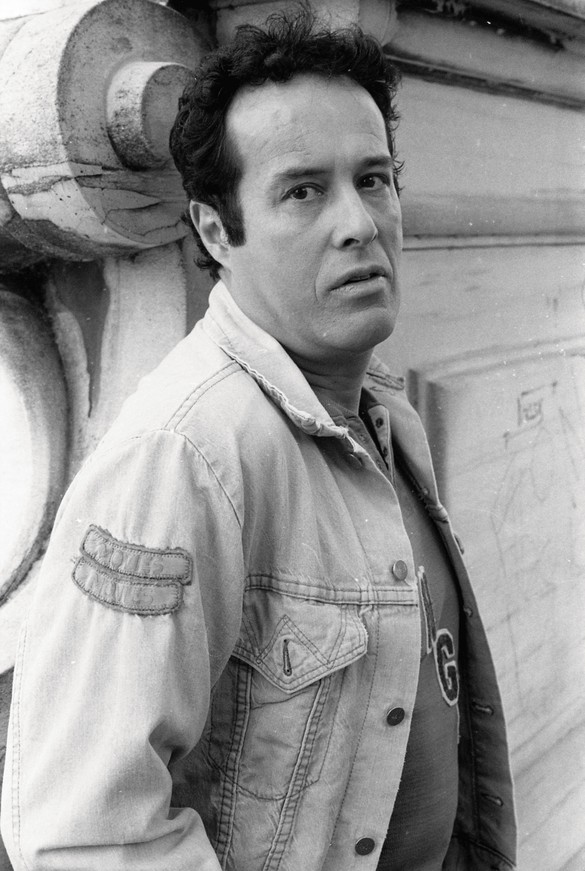

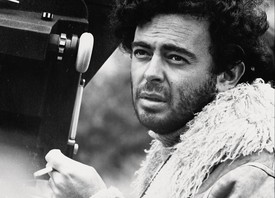

The teenager in his bedroom who changes the world: such was his debut with Fireworks, which first screened publicly in 1947. It was the ultimate home movie, shot during a home-alone episode while the parents were away, probably over Christmas 1946, when he was still nineteen.

Part of his genius was his ability to bridge liminality, to cross the border of waking and sleep, and to capture the vast interiority of our inner psychic spaces—and to do so on black-and-white 16mm in his parents’ living room.

Kenneth led, by preference, a monastic existence. He never had a long-term partner, describing himself as a “lone wolf,” although he had his obsessions, some of whom were cast as his “Lucifer.” He did sometimes live with friends, notably with Marjorie Cameron in Silver Lake, Los Angeles, with Anton LaVey at his “Black House” in San Francisco, and with Samson De Brier in Los Angeles at the Barton Avenue bungalow where Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954) had been filmed. Inauguration took its title from Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan,” which describes an initiate of the mysteries, someone who had gone there and back again. His works covered the great triumvirate of our times: sex (Fireworks), drugs (Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome), and rock ’n’ roll (Scorpio Rising, 1963).

He liked children to a degree; he was my daughter’s godfather. He read voraciously, especially early sci-fi and fantasy, and the Symbolists and Decadents. He collected Rudolph Valentino artifacts and, when he had the space, maintained a shrine. If he had his own place, he favored strong, very intense colors, sometimes in high gloss. While he had a refrigerator, it contained nothing but film stock. He barely slept, suffering from a treatment-resistant form of insomnia. He was terrible with money. When he had some, as he occasionally did, he bought things with little thought of the price, often for others (his generosity was legendary), and soon found himself broke again. When he could, all through the ’50s and ’60s into his more threadbare ’70s, he dressed well, buying his clothes mainly in France. While he seemingly knew everyone, he was anything but a snob, accepting his friends, limitations and all, with good humor. He was subversive—he felt strongly that there was a great deal in this world in need of immediate subversion—but wasn’t tiresomely militant about it.

In England he befriended Gerald J. Yorke, a friend and colleague of Aleister Crowley’s who had amassed a major archive of Crowley’s papers. It was Yorke who supervised his education in Magick, giving him a solid grounding in its literature and a wealth of unpublished material on Crowley’s religious system, Thelema (Greek for “will”). Crowley founded Thelema after receiving its foundation text, The Book of the Law, through direct-voice dictation from a preterhuman intelligence in Cairo in 1904. Its central tenet is that the cultivation of the True Will, through the application of Crowley’s system of Magick, can unlock innate genius. Crowley and the teachers he trained through his twin organizations, the A.·.A.·. and the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.), taught and initiated artists as diverse as the painters Cameron, Xul Solar, and Ithell Colquhoun, the writers Mary Butts, Fernando Pessoa, and Malcolm Lowry, and the filmmakers Harry Smith and Kenneth Anger, all of whom left evidence of their immersion in Thelemic doctrines and practices, which are an interpretive key to their work. Anger was the most overt in acknowledging Crowley’s influence.

Thelema teaches that a new age of the child has dawned to supersede the matriarchal and patriarchal ages of the past, and that humanity is now evolving from separated sexes to embody both sexes in every person.1 Anger identified the sometimes aberrant birth-pangs of this new age in youth countercultures. In a revealing 1966 San Francisco Chronicle profile, he explained that “his interest in the extremist groups is that of an intelligence agent for Thelema rather than as a sociologist. It’s ‘keeping up with the enemy.’” He added that “In all such groups there’s something operating. I call it tribal sorcery, tribal magic, on a very simple level. Its appeal to people is basically irrational.”2 In an even more revealing 1967 New York Times profile he remarked that “his fascination with magic or fantasy ‘at the point where it meets reality’ is what led him to study American cults” like those that had formed around motorcycles (Scorpio Rising) and drag racing (Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1965).3

In his Magick in Theory and Practice (1929), Crowley defined Magick as “the Science and Art of causing Change to occur in conformity with Will.”4 In competent hands, he believed, a well-designed ritual can release spiritual impulses that trigger changes on the “inner planes” that underlie reality and affect the future. This is the very definition of a game changer. Anger repeatedly showed his acute awareness of this principle in his work, whose titles themselves indicate his ritual intent: Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, say, or Invocation of My Demon Brother, or Lucifer Rising.

Anger was a master colorist in film, learning a sophisticated color theory from a book called 777 (1909), edited anonymously by Crowley, which published the secret Golden Dawn society’s color scales for the first time. One of its innovations was to distinguish between reflective and transmitted (i.e., transparent) colors, a crucial distinction for a filmmaker who worked, as Anger did, with careful costume and set coloration and Ektachrome photography and processing. The “Sacred Mushroom Edition” of Inauguration was printed by Kenneth himself on A through E rolls in gorgeous color with sophisticated superimposition. He was a master photographer when he did the shooting himself, but his ability to control a cameraman was even more impressive.

What was game-changing about Anger’s films was their encoded spiritual messages urging Crowley’s message of Thelema: “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” “Love is the law, love under will.” “Every man and every woman is a star.” The films carried this message not, usually, in too didactic a way, but in their dynamic and the feelings they induced, appealing to what is individual and rebellious in their viewers. Thelema does not convert, but it can inspire. Innumerable gay cinemagoers must have left their local theater or college screening room feeling empowered, celebrated, and validated—no small thing fifty years ago.

1The Master Therion [Aleister Crowley], Magick in Theory and Practice (Paris and London, 1929 (1930)), chap. 5.

2Kenneth Anger, quoted in John L. Wasserman, “Witchcraft by Anger,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 30, 1966.

3Elenore Lester, “From Underground: Kenneth Anger Rising,” New York Times, February 19, 1967.

4Master Therion, Magick in Theory and Practice, Introduction.