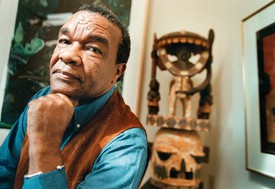

Michael Auping is an independent curator and art historian. He is well known as a curator and scholar of Abstract Expressionism, and has organized exhibitions of Arshile Gorky, Philip Guston, and Clyfford Still. He has also organized major exhibitions of Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, and Susan Rothenberg. His latest book, 40 Years: Just Talking About Art, was published by Prestel in 2018.

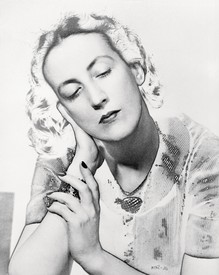

For a half century, Connie Lewallen was a curatorial force, alternating between New York and California—a bicoastal pioneer. The path to becoming a curator of contemporary art in the 1970s, when Connie began her career, was not just a matter of academic credentials; it was about a certain kind of hustle in which you learned to pivot among places, evolving aesthetics, and the distances between art history and the art of the moment. Energy and intellect had to be fused with determination and perseverance.

Growing up on the West Side of Manhattan, Connie traveled to California in the late 1960s to get a masters degree in art history from San Diego State. Her thesis focused on Mark Rothko. At the time, the content of Rothko’s abstractions was a deep and challenging subject, and scholarship on it was only in its early stages.

Afterward she moved back to New York, where she made her first of many daring career pivots. Connie was relatively unique among curators in that her early initiations were spent in commercial galleries. At that moment a foray into the gallery scene was typically considered a path to the dark side. In fact, however, it was a bonus, because all the action was in galleries; museums had not yet wholeheartedly embraced contemporary art as they do today.

Connie had a fortuitous start as a gallery attendant: she sat at the front desk of New York’s cutting-edge Bykert Gallery, which hosted pioneering shows of young, soon-to-be-well-known artists associated with Minimalism, Post-Minimalism and Process art (Chuck Close, Brice Marden, Dorothea Rockburne, Barry Le Va, Alan Saret, Judy Rifka). It was the right time and place for Connie to hear directly from artists about their work and to learn how to talk about difficult art as it was making its precarious entrance into contemporary culture.

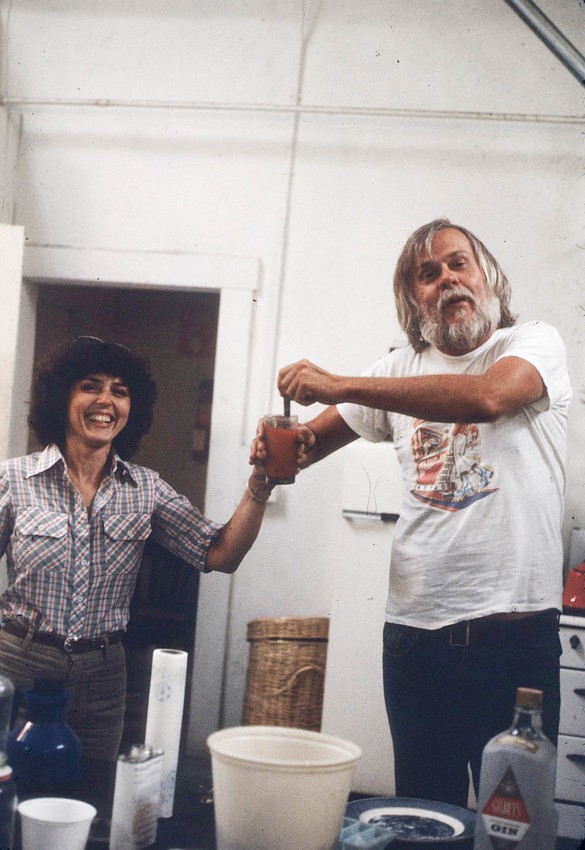

In the early ’70s she moved back to California and settled into the burgeoning Los Angeles art scene. There she quickly found work at the Cirrus Gallery, which hosted exhibitions and published prints with some of the best artists working in Southern California, including Ed Ruscha and Vija Celmins. She was later lured to the Broxton Gallery, owned by a young Larry Gagosian. She had good ideas, and Gagosian, who was at an early point in his own career, embraced them. He had offered her a big raise (a whopping $25 more a week, which was a lot back then) to leave her previous job and she remembered that time fondly, even sometimes recalling, “He let me bring my kids to work when they weren’t in school and I couldn’t get a babysitter.” In those early years, Connie’s expertise was influential in shaping the gallery’s burgeoning program, which spanned between classic modernism and the new avant-garde.

In 1977, after her time at Gagosian, Connie teamed up with Morgan Thomas to create the ThomasLewallen Gallery in a small second-floor space in Santa Monica. Their roster was a smart and diverse group that consisted mostly of Conceptual artists but also featured a few important painters. Connie was the one you talked to when it came to the Conceptual ones; it wasn’t that she didn’t like painting, more that it didn’t need her as much. Painting had been around for centuries and was attended by a relatively simple, formalist vocabulary. Conceptual art was new and complex, and it benefited from her thoughtful and engaging explanations.

I remember visiting their gallery when they introduced LA to the young, relatively unknown artist Jonathan Borofsky, who had just moved to the city from New York. She installed what seemed like hundreds of his Dream drawings on small sheets of paper, hung floor to ceiling in the stairwell that led up to the tiny gallery. We smoked and talked about them for hours. Ten years my senior, she had the youthful evangelism of a radical and energetic teacher. It was fun and enlightening, but talking to a poor graduate student like me didn’t pay the rent. Connie was always about ideas, not profit. She later reminded me that not a single drawing was sold from that show.

Maybe it was her interest in teaching (and a little of that Connie hustle) that soon took her north to the University Art Museum in Berkeley, where she made the pivot to museum curator. There she capitalized on her special calling in the art world. The Bay Area had a large number of interesting Conceptual artists who were basically ignored by New York and Los Angeles. Bay Area Conceptualism didn’t have as much of a popular-culture element as LA art, meaning it seemed less funny, more sly and darkly political and metaphysical. It was just the new challenge she needed.

She befriended, and often supported, more of those artists than I can name (Terry Fox, Howard Fried, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, David Ireland, Paul Kos, Suzanne Lacy, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Tom Marioni, Bruce Nauman). She paid particular attention to Nauman’s early development at UC Davis and in San Francisco. Through her traveling shows and writing, Connie put the history of Bay Area Conceptualism on the map. In 2001, she brought the Conceptualism of Southern California together with that of the Bay Area in her critically acclaimed exhibition State of Mind: New California Art c. 1970 (which she cocurated with Karen Moss).

Meanwhile, she never lost her need for New York. She loved visiting New York galleries . . . every one of them, or so it seemed. Many of us have stories of being worn out by accompanying her on forced marches through the New York shows. There was rarely time for lunch.

When she married the poet Bill Berkson, her trail between San Francisco and New York grew even deeper. They had Bill’s place in New York and Connie’s in San Francisco, and they had a voracious appetite for learning about new art in both places. Just having dinner with them could be both enlightening and exhausting. I am someone who has followed contemporary art for almost fifty years, and the conversation often went something like this: Connie: Did you see that show? Me: No . . . Connie: What about the show at that little gallery on the Bowery? Me: No . . . And so on.

When Bill died, there was only a short pause in the action. Even the covid-19 pandemic didn’t really slow her down. Stuck in her house in San Francisco, she found Phong Bui’s Brooklyn Rail and became something of a California correspondent, continuing to proselytize through the magic of Zoom. And she wrote an article on the San Francisco Art Institute for Gagosian Quarterly, exploring the challenges that faced an institution she saw as hugely influential for the many artists who had passed through it over the course of its 150-year history.

When Connie suddenly died, at the age of eighty-two, all her friends on both coasts could say was “But she was just here. I saw her last week.” And they would all be right. Now, in her startling absence, we can only be grateful for the energy and ideas she transmitted.