Constance Lewallen (1939–2022) was adjunct curator at the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, where she was first matrix curator, subsequently senior curator, and organized many major exhibitions. Photo: Nathaniel Dorsky

It’s a cruel irony that just as the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) is celebrating its 150th anniversary, it is struggling to survive. Alas, it is not an isolated case: many institutions of higher learning, especially art schools, with fewer than a thousand students have been under financial strain for a number of years. According to Deborah Obalil, president and executive director of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design (AICAD), most have needed to change their operating structure in one way or another. Some stopped granting degrees (Lyme Academy of Fine Arts, Old Lyme, Connecticut, in 2019); some have merged with colleges and universities (School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, with Tufts University, in 2016); some, such as the Memphis College of Art, have closed altogether (2020).1

Before we get into the specifics of what led to SFAI’s current crisis and what is being done to overcome it, we should know something of its remarkable history. The school’s roster of teachers and students, to say nothing of the guest lectures, conferences, and exhibitions that have taken place there over the years, speaks to why it has occupied such a critical role in the cultural life of the region.

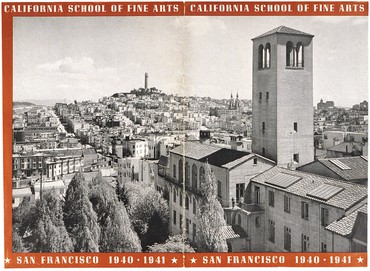

The oldest art school in the West was born in 1871 in the living room of a local painter, J. B. Wandesforde, who convened a group of artists and writers to discuss the establishment of a society to promote the arts. Until its recent travails, the school was a center of artistic activity in the Bay Area. In its early days, as the California School of Fine Arts, it was located on Nob Hill; in 1926 it moved to Chestnut Street, on Russian Hill, to a campus with sweeping views of the city and the bay. The design, by architects Bakewell & Brown, was inspired by a typical Italian hillside town, with its tower, piazza, and cathedral (the school’s gallery).2

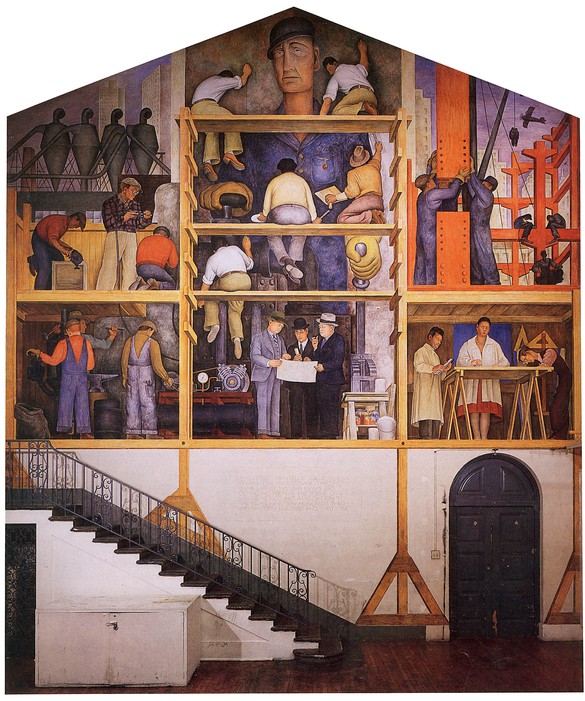

In 1930, Henri Matisse visited the new campus. “He said he had never seen such magnificent lighting and working conditions in Europe,” according to an account of his tour.3 Not long after, Diego Rivera created his monumental fresco The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City (1931) in the school’s student gallery, where it remains. The fresco portrays the creation of both a city and a mural and depicts several of the people who commissioned the work, as well as the artists, engineers, architects, and sculptors involved, but, as always, Rivera celebrates the common laborer, here epitomized by the outsize figure in the center. Rivera himself, paint brush and palette in hand, is shown from the rear, sitting on a beam as he supervises the project.

Rivera created three murals in San Francisco, all intact and available to the public. The SFAI mural is considered the standout, a prime example of his mastery of the medium, and has made the school an international destination for the study of his work. In 2019, Patti Smith performed in front of it; a passionate admirer of the Mexican artists of his generation, particularly Rivera himself and Frida Kahlo, and of the revolutionary spirit of their country, she wrote of the event, “It was a moving experience, to sing so close to his work. The historic SFAI is a jewel, a work centric atmosphere of communal process and artistic evolution.”4

Since the middle of the twentieth century the school has been at or near the heart of each new national and regional artistic movement. After the end of World War II, its enrollment surged in part due to an influx of older artists taking advantage of the GI Bill. In his role as president of the school, legendary educator and curator Douglas MacAgy hired Elmer Bischoff, Dorr Bothwell, former student Richard Diebenkorn, Claire Falkenstein, David Park, Hassel Smith, and Clyfford Still, and invited New York artists Ad Reinhardt and Mark Rothko to teach summer sessions, making the school a center for Abstract Expressionism. Although Still was only at the school from 1946 to 1950, he was especially influential, espousing a romantic, intensely anticommercial view of the role of the artist that, as we shall see, persisted across departments long after he departed.

The Painting Department continued to be the engine of the school. Major figures of the Bay Area Figurative movement Theophilus Brown and Paul Wonner, in addition to the aforementioned Bischoff, Diebenkorn, and Park, taught there for a time, and many students would become prominent artists, among them Dara Birnbaum, Don Ed Hardy (responsible for elevating tattoo to a fine art), Mike Henderson, Paul McCarthy, and Jason Rhoades. Kehinde Wiley, whom Barack Obama chose to paint his official presidential portrait in 2018, has said of his time there, “SFAI is where I honed in on my skills and identity as an artist, and I’ve carried that experience with me throughout my career.”5

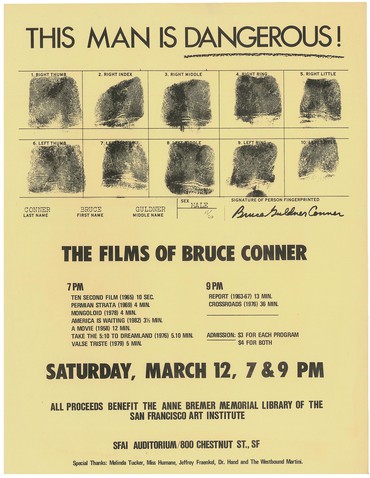

In the 1950s, it was the Beat era. Allen Ginsberg famously gave his first reading of Howl in 1955 at the Six Gallery, which was run by artists of the school. Jay DeFeo taught at SFAI even as her magnum opus The Rose (1958–66; now in the collection of New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art) slowly deteriorated for years behind a temporary wall in the school’s conference room (it was conserved in that same location in 1995). DeFeo and fellow teachers Joan Brown, Bruce Conner, Wally Hedrick, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Kenneth Rexroth were key figures in the artistic and literary community that gave rise to the San Francisco Renaissance, a blossoming of underground art that transformed the city into a center of the avant-garde. Conner would later propose an undergraduate seminar described in the course catalogue as “Wasted Time: unproductive activity of no practical application.”6

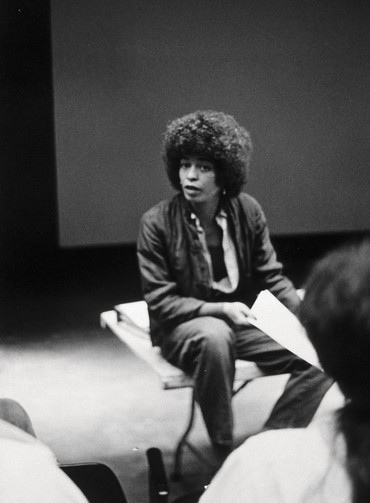

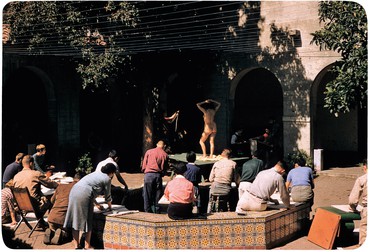

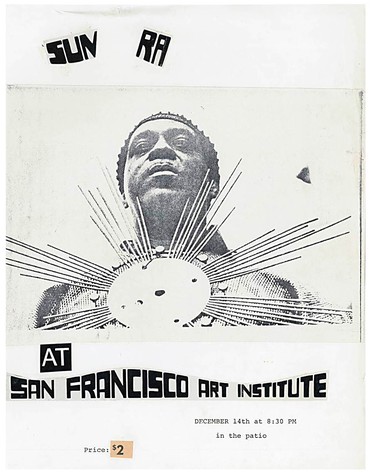

A decade later, Peter Selz included SFAI alumni Roy De Forest, Peter Saul, and William T. Wiley in his 1967 exhibition Funk, at the University Art Museum, Berkeley, which gave a name to this regional movement characterized by the personal, the antiformal, the irreverent, and, often, the crude. By that time SFAI was fully immersed in the counterculture, from anti–Vietnam War protests to the Black Liberation Movement. The gallery showed psychedelic rock posters in November 1966, Sun Ra performed in the courtyard in December 1968 and again in April 1969, and mind-expanding drugs were prevalent among faculty members and students. In that spirit, in 1966, several SFAI photography students organized The Experience, an exhibition of “hallucinatory photography among five people over a twelve-hour period” in which the artists took hallucinogenic drugs and collectively documented the experience.7 Annie Leibovitz began photographing for Rolling Stone in 1968 while still a student (she became the magazine’s chief photographer in 1973).8 SFAI faculty member James Robertson designed Artforum magazine, its square format mimicking that of the school’s catalogue; and alumni photographers Ruth-Marion Baruch and Pirkle Jones documented Black Panther rallies, Haight Street hippies, and Sausalito’s off-the-grid houseboat community. Angela Davis joined the faculty five or so years after being on the FBI’s Most Wanted list.

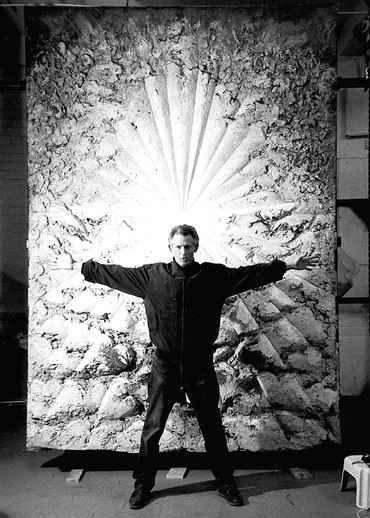

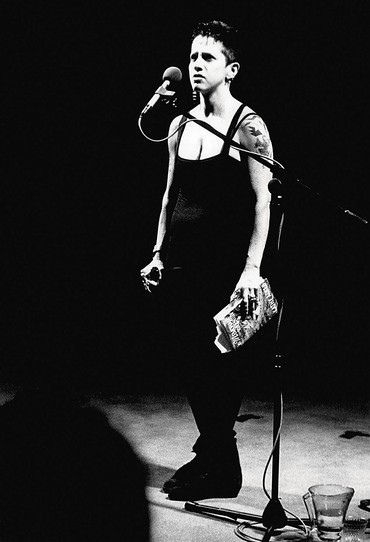

The school responded to the emergence of experimental performance, video, and Conceptual forms in the 1970s by establishing the Performance/Video Department (later renamed “New Genres”). The main members of the area’s nascent Conceptual scene populated the department: Howard Fried was the first chair, followed by Paul Kos (a former painting student at the school) and, soon after, Sharon Grace and Doug Hall. Eventually, former student Tony Labat joined the faculty, along with Kathy Acker. Guest instructors and visiting artists over the years have included Marina Abramović, Vito Acconci, Laurie Anderson, Chris Burden, Terry Fox, the Kipper Kids, Shigeko Kubota, Gerhard Lischka, Mary Lucier, Linda Montano, Nam June Paik, David Ross, and Bonnie Sherk. Karen Finley was one of the department’s first students, and Nao Bustamante, Kota Ezawa, and David Ireland are among its many other notable graduates. The atmosphere was nonhierarchical, irreverent, open to all forms of expression. Kos described it as “arrogant and pompous. And humble and unassuming . . . brusque, brazen, and alive, welcoming and scary.”9 Former student Carol Szymanski remembers, “Ours was a small, close-knit department, with no interaction with the other departments. I felt as though I was experiencing something very important about what art and life were and could be. Nothing was saddled with convention or history. It was all about the act of creating and discussing.”10

Barry McGee, Alicia McCarthy, Ruby Neri, and Rigo 23, all SFAI graduates, were the core artists of San Francisco’s Mission School, which flourished during the 1990s and 2000s and grew from the region’s vibrant mural and graffiti street art. McGee summed up his experience as a student: “I think about all the weird kids and teachers, how we all came together in SF at 800 Chestnut. It’s one of the strongest art communities I have been involved with. SFAI is steeped in SF art history . . . the real deal. Its location and relaxed campus make it one of the last great art schools in America.”11

From the beginning, film and photography have been central to the school’s curriculum. For starters, the first public showing of a moving picture occurred there in 1880 with Eadweard Muybridge’s presentation of his Zoopraxiscope. In 1945, Ansel Adams founded the country’s first department of art photography at SFAI, and hired leading photographers of the day including Imogen Cunningham, Dorothea Lange, Lisette Model, Edward Weston, and Minor White. Other notable faculty followed: Jones, Ellen Brooks, Jerry Burchard, Linda Connor, John Collier, Reagan Louie, Larry Sultan, Henry Wessel, and current chair Lindsey White. Among those who studied in the department are Jim Goldberg, Sharon Lockhart, Mike Mandel, and Catherine Opie. While technique was taught in the foundation classes, the stress was always on innovation and experimentation. Leibovitz discovered her true talent was for photography in the department, although she was a painting major. (She also took a sculpture class taught by Bruce Nauman.) According to Leibovitz (and the same sentiment was expressed by several other former students), “A lot of schools teach you technique. At the [San Francisco Art Institute], they teach you how to see.”12 Former student Jane Reed recalls, “We were a very close-knit group of people dedicated to making art for the creative impulse not the commercial return.”13

SFAI’s Film Department, established in 1969, became a home to the country’s burgeoning avant-garde filmmaking scene. (Well before that, beginning in 1947, the first noncommercial film classes anywhere were taught at the school by Sidney Peterson. Stan Brakhage studied at the school in the early 1950s.) Robert Nelson, the first filmmaker hired when the Film Department was established, set the tone, stressing self-expression and experimentation. Eventually the faculty included filmmakers James Broughton, Ernie Gehr, Lawrence Jordan, George Kuchar, and Gunvor Nelson, as well as famed film curator Edith Kramer. The department also established a residency program that attracted Chantal Akerman, Hollis Frampton, Carolee Schneemann, and others. Steve Anker, director of the San Francisco Cinematheque and, later, dean at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), Los Angeles, as well as a faculty member at SFAI, organized regular screenings in the auditorium. Even when video was attracting students in the 1980s and ’90s, Anker would write, “Most students were still excited by the sensuality of celluloid.”14

The department continues its commitment to avant-garde film while also teaching narrative and documentary approaches. Graduates include the Taiwanese installation artist Su-Chen Hung; Ruby Yang, who in 2007 received the Short Film Documentary Academy Award for The Blood of Yingzhou District, about HIV in China; Lance Acord, cinematographer on Sofia Coppola’s award-winning Lost in Translation (2003); and Kathryn Bigelow (a painting major who also studied film), whose film The Hurt Locker (2008) made her the first woman to win a Best Director Academy Award. In accepting the honorary doctorate bestowed on her by the school in 2013, Bigelow said that “art education really is vital and unique.”15 Documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras, who studied experimental filmmaking at SFAI, won the Academy Award for best documentary feature for Citizenfour (2014), and Peter Pau, who studied photography with Jones and filmmaking with Kuchar at the school in the 1980s, won an Academy Award for Cinematography for Ang Lee’s movie Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000).

Sculpture, too, is vital to the program. Sargent Johnson, a pillar of the Harlem Renaissance, graduated from the school in 1923. In later decades, some of the area’s leading ceramic artists—Jim Melchert, Ron Nagle, Manuel Neri, and Richard Shaw—taught there full- or part-time, and Nauman was a part-time instructor in the department in the late 1960s. Stephanie Syjuco wrote of her experience as a student in the department,

SFAI has always been super experimental—many students were pushing the envelope in terms of performance, new genres, and conceptual works. . . . the program at SFAI created feral artists. . . . SFAI didn’t seem to care about training students toward even thinking about [the art market] at all. . . . The legacy of SFAI is huge and I will always remain thankful that I went there. SFAI felt a bit out of time and place, adhering to the primacy of a fine-arts degree over the decades while other schools added architecture and design programs to bolster their student numbers and financial support. But I do appreciate the purely fine arts focus it had, despite its potentially unmarketable reality. This defiance feels very much like the spirit of SFAI.16

The Humanities Department’s outstanding teachers attracted students throughout the school. Poet and art critic Bill Berkson taught art history and poetry classes. One of his students was singer/songwriter and visual artist Devendra Banhart, who says, “I am certain that without Bill Berkson’s guidance and encouragement I would 100% not have a career, no doubt about it.”17 Other faculty included Davis (aesthetics), composer Charles Boone (music), and Bernard Mayes, the openly gay ordained priest and radio broadcaster who, in 1961, having learned of San Francisco’s high suicide rate, singlehandedly created the nation’s first suicide hotline.

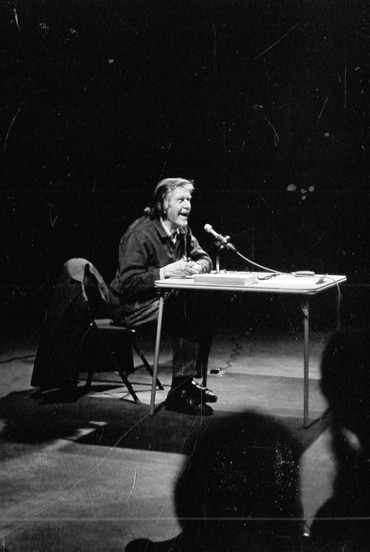

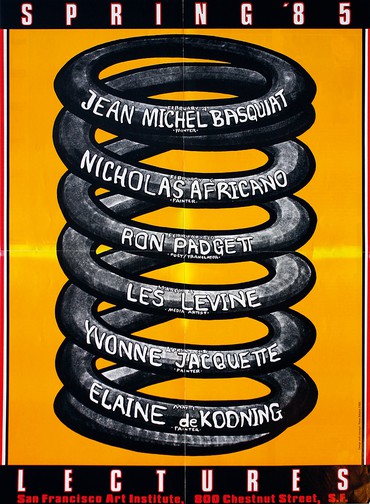

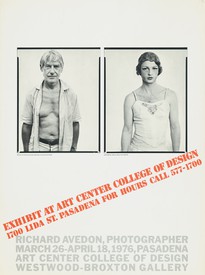

Given the sheer breadth and ambition of the lectures and public programs that SFAI has hosted, the question is less who has spoken at the school than who hasn’t. For over twenty years, Berkson ran a speaker program that included not just artists of all stripes, from Robert Rauschenberg to David Hammons, but also prominent art critics and curators such as Arthur Danto, Lucy Lippard, and Walter Hopps, internationally recognized poets (John Ashbery), and cultural figures from Emory Douglas of the Black Panthers to John Cage and Rem Koolhaas. As for conferences, in 1949 MacAgy hosted the landmark “Western Roundtable on Modern Art.”18 The object was simply to examine the art of that moment. To name just a few of the participants: cultural anthropologist Gregory Bateson (who also taught at the school), the artists Marcel Duchamp and Mark Tobey, the critic and art historian Robert Goldwater, the composers Darius Milhaud and Arnold Schoenberg, and the architect Frank Lloyd Wright, whose antipathy to the avant-garde was on full display. Seventeen years later the school sponsored another conference, “The Current Moment in Art,” to assess the art of that era. It featured Hopps, Selz, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Larry Rivers, Frank Stella, Wayne Thiebaud, and others.19 Between 1989 and 1991, former student and painting faculty member Carlos Villa organized a series of symposia, part of his “Worlds in Collision” project.

I would be remiss if I didn’t recognize the importance of the school’s gallery, which over the years and under its various directors has mounted many provocative shows.20 Among them: The Hot Rod Aesthetic (1968); American Primitive and Naive Art (1970);21 18' 6" × 6' 9" × 11' 2 1/2" × 47' 11 3/16" × 29' 8 1/2" × 31' 9 3/16" (1969), which brought the work of artists such as Michael Asher, Edward Kienholz, Joseph Kosuth, and Lawrence Weiner to SFAI and was an early example of institutional support for the Conceptual movement; and Other Sources: An American Essay (1976), a pioneering exhibition and performance series, organized by Villa, that celebrated cultural diversity and a more inclusive art world by showcasing the work and cultural traditions of artists of color. Another groundbreaking exhibition, Touch: Relational Art from the 1990s to Now (2002), cocurated by Karen Moss and Nicolas Bourriaud, featured an international roster of artists associated with Bourriaud’s concept of “relational aesthetics,” the first exhibition in the United States to fully explore the phenomenon of social interaction that Bourriaud had identified.

Despite its stellar history, the school reached a crisis point in March 2020. What went wrong? SFAI has had financial difficulties off and on for years but always rose phoenixlike from the proverbial ashes. There is not just one cause of the current dire circumstance; as noted earlier, SFAI is one among many art schools that are in jeopardy. Historically, most started as community-based art centers. Once they shifted to the category of degree-granting colleges, they were required to increase administrative staff to satisfy nonprofit guidelines and federal regulations, such as Title IX. AICAD’s Obalil observes that such costs never level off; they always increase.22 Most art schools lack an ample endowment and traditionally have not attracted major philanthropy. Consequently, they rely on tuition. That leaves two options: raise tuition, which is usually quite steep (SFAI’s, which is fairly typical, is around $45,000), or increase the size of the student body. In the case of SFAI, neither one, nor even both, can meet the yearly operating budget of approximately $18 million.

In fact, enrollment in SFAI has fallen off in recent years from its peak of around 1,000 in the late 1960s and early ’70s to 300 or so in recent years. This was due in part to rising tuition costs and in part to a decrease in the number of foreign students, who traditionally have made up a good portion of the student body and who pay full tuition. Most other students take out substantial loans to finance their education, a deterrent when a fine-art degree doesn’t clearly lead to a financially secure career. In this way, SFAI’s dedication to a purely fine-arts education has made it difficult to attract students in today’s economy. Those art schools that also offer design and other applied arts, such as the California College of the Arts (CCA), based in San Francisco, have fared better.

Then there was the decision to develop a second campus. In 2015, the school secured a sixty-year lease on one of the piers at nearby Fort Mason, a former military site administered by the National Park Service and now home to nonprofit arts-oriented venues. The school struck an attractive deal whereby Fort Mason offered a very favorable lease. In return the school was responsible for a much-needed, costly renovation. It seemed like a good idea at a time when enrollment was still relatively healthy and the school had outgrown the rented, rather dismal graduate studios and classrooms in the Dogpatch neighborhood across town. However, just as the new campus opened in 2017, enrollment began to decline (the school had lacked a director of admissions for over a year). Moreover, the fundraising goal for the build-out was not met—SFAI’s alumni base had been somewhat mystifyingly neglected—raising the debt to $19 million.23 This resulted in a bank loan, the collateral for which was the Russian Hill property and all other assets of the school. The yearly interest was crushing.

By March 2020, it looked as if the school might not make it this time. The coup de grâce was that, just as negotiations to merge with the University of San Francisco, a local private Jesuit university, were all but finalized, the deal fell victim to the covid-19 pandemic and other contributing factors. Once the merger collapsed, then-SFAI-president Gordon Knox and board chair Pam Rorke Levy announced that the school would not enroll new students in fall 2021 and laid off adjunct faculty and all but a skeleton staff. That so alarmed the community that there was a significant uptick in fundraising, which, along with the receipt of a second round of funds from the federal Paycheck Protection Program, averted the school’s closure. But what really saved the day was that the board was able to renegotiate the bank loan by reaching an agreement with the University of California, which assumed the loan and allowed SFAI six years to repay the debt, including a year of relief. The school was also able to secure permission from Fort Mason to sublet the new campus and found a short-term tenant, with others expressing interest in renting part or all of the space in the future—a viable arrangement as long as the tenant fits Fort Mason’s guidelines that it be a nonprofit.

In July 2020, the board created the Reimagine Committee, made up of SFAI faculty, alumni, staff, and artists unaffiliated with the school, along with local cultural leaders and external consultants. This body was charged with addressing the school’s problems and coming up with ideas on how to make it healthier economically and more relevant to today’s world. The committee identified many of the school’s weaknesses—a lack of transparency in its decision-making, for example—and proposed, among other ideas, decentralizing the current organizing structure in favor of collective leadership (a bottom-up rather than a top-down approach). Unfortunately, an adversarial relationship between the board and the committee ensued when the committee, which felt its findings weren’t sufficiently appreciated, announced that it wouldn’t present them to the board until then-chair Levy stepped down. Levy and other stalwarts had stayed on through the worst of the crisis and had fought to enable the school to stay open and to retain its tenured faculty.

The school was the subject of a great deal of negative press when it was leaked that negotiations were underway to monetize the Rivera mural. According to Levy and other trustees, it was the board’s fiduciary responsibility to investigate all avenues to shore up the school’s finances in the short term, including by selling the mural, while exploring longer-term solutions. The fresco was appraised at approximately $50 million, and it was hoped that a partner would endow it in place.24 To that end, trustee and architect John Marx came up with a brilliant plan that would allow the fresco to remain in its present location by opening the gallery to the public (the gallery has an exterior wall facing the fresco). It could then become a pocket museum, classroom, and center for the study of fresco, conservation, Rivera, and the Mexican mural movement.

Former faculty artist Mildred Howard had drafted a petition signed by dozens of artists (both affiliated and unaffiliated with the school), curators, arts-organization leaders, and gallerists across the country, urging the sale of the fresco only as a last resort. Unfortunately, the press focused on the possibility of removing the mural, which was not the board’s preferred option; in fact it was vehemently opposed. For one thing, while the removal of the fresco from the wall is technically possible (although not without endangering it), on a symbolic level it would be tantamount to tearing the soul out of the school. This is a moot point now, since the fresco is up for landmark status, which, if achieved as expected, would decrease its value. (The Chestnut Street campus is itself landmarked.) The mural could still generate funds, however, if another donor is identified who would endow it in place, or by making it the focus of a public space such as Marx conceived, or, ideally, both.

The new board chair, the photographer, educator, and alumnus Lonnie Graham, is exploring ways to keep the school afloat for three years (he calls it a “runway”) while preparing for a long-term solution. To that end, he and the other trustees, now numbering seven (all but three had resigned during the Rivera controversy), have embarked on a series of listening tours with faculty, staff, alumni, and current students (who seem especially energized by being included) in order not only to hear their points of view but also to establish much-needed trust among these groups. If all goes well, the plan is to be able to rehire those adjunct teachers and staff who were laid off. The school has remained open (a handful of students will graduate this spring) and is expecting to enroll approximately 50 students for fall 2021, 100 the following year, and 300 the year after that, numbers that should allow time to develop a sustainable operating structure.

There are plans for a 150th-anniversary exhibition and benefit sale at the school in November of 2021. Titled Looking Forward, it will include a large selection of works by artists, both local and national, donated by the artists themselves, as well as by alumni, friends, collectors, foundations, current and former trustees, and prominent galleries. The following is a partial list of the artists to be represented: Cunningham, Diebenkorn, Ireland, Kienholz, Opie, Diane Arbus, Michael Heizer, Hans Hofmann, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Hung Liu, Julie Mehretu, Gary Simmons, and William T. Wiley. In addition, major works by Hall, Rivers, and Thiebaud are being offered for sale before the exhibition.

The long-term solution would most likely be a partnership with a college or university, or perhaps an alliance of art schools with complementary strengths. No one believes that returning to the way the school has operated in the past could or should be the goal.

It must be noted that one contributor to the school’s troubles has been a lack of consistent leadership: between 1987 and 2021 there were six presidents or interim presidents. Currently, SFAI has no president but rather a chief academic officer and an interim chief operational officer. Perhaps it’s unnecessary to have a single president; instead, several officers could share responsibility for the governance of the school according to their expertise. Meanwhile, the covid-19 pandemic has shown that there are educational models that do not require on-site presence. Some students might be on campus, others could learn from afar. The same goes for faculty, guest teachers, and speakers. San Francisco, after all, is situated in the center of the tech world and should be in an advantageous position to devise new models.

Where do things stand now? The school’s debt has been deferred and recruitment and marketing officers have been retained. While working to increase enrollment, the board is also seeking a guarantor for a $7 million bridge loan. Several new, promising trustees have joined the board and there has been some impressive success in fundraising. The Access 50 Scholarship Fund, established under Knox’s presidency and directed at people of color, has received donations from artist Sam Gilliam and from Julie Wainwright, founder and CEO of RealReal, an online consignment market for luxury goods, who transferred a substantial amount of stock. The fund is currently valued at $750,000, and the first scholarships will be awarded in the fall of 2021. Expected income from leasing the Fort Mason campus might well yield $1 million a year over the fifty-five-year duration of the lease, which the school can borrow against. Over time, the new leadership is committed to implementing many of the Reimagine Committee’s suggestions, not least of which is finding new, more equitable and sustainable models that will enable it to lower tuition.

It seems that the school has been able to retreat from the abyss.

Peppered throughout this text are quotations from former students about their love for the school. Why does it inspire such passion? According to what they have said over and over, it is because of SFAI’s unique commitment to a purely fine-arts education that teaches students not only to be artists but, just as important, to think and see, to innovate and experiment. The school isn’t for everyone. Some former students cite the prohibitive cost and the lack of sufficient facilities, but most have positive, even rapturous memories of their time there. Many appreciate that they were treated as artists from day one; others cite the cultural and artistic diversity of the student body, and still others the support of the faculty.25 Dara Birnbaum wrote simply, “I was able to fall in love with art there.”26

I wish to acknowledge the many people who helped me with this article. I couldn’t have written the history of the San Francisco Art Institute without the good-natured help of Jeff Gunderson, librarian and archivist at the school, and his assistant Rebecca Alexander, whose chronology I drew upon and who helped me identify sources and answered what must have seemed endless questions. Steve Anker guided me through the history of the school’s Film Department and Linda Conner did the same for the Photography Department. I couldn’t have navigated the twists and turns of recent events and future plans without the assistance of Deborah Obalil, Lonnie Graham, John Marx, Doug Hall, Jennifer Rissler, Gordon Knox, Jeremy Stone, Lindsey White, Leonie Guyer, and Joyce Burstein. Finally, I am grateful to Judy Bloch, who deftly edited the essay, as she has so many of those I have written in the past.

1Deborah Obalil, telephone conversation with the author, March 9, 2021.

2Bakewell & Brown designed many San Francisco landmarks, including City Hall, and Arthur Brown Jr. later designed Coit Tower. A 1969 addition to the campus was designed by Paffard Keatinge-Clay. The school changed its name from California School of Fine Arts to San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) in 1961; for simplicity, the school is referred to by its current name throughout this article.

3San Francisco Art Association Bulletin, April 1930, p. 4. SFAI Archives, Anne Bremer Memorial Library, SFAI.

4Patti Smith, Instagram post, thisispattismith, January 19, 2019. Available online at https://www.instagram.com/p/Bs1Mcx_hpUx/ (accessed June 7, 2021).

5Kehinde Wiley, quoted in SFAI, “Kehinde Wiley to deliver keynote address at San Francisco Art Institute Commencement and receive honorary degree,” March 21, 2018. Available online at https://sfai.edu/uploads/about-sfai/2018_SFAI_Commencement_Release_03212018.pdf (accessed June 7, 2021).

6Gunderson, illustrated chronology, 1954–69, unpublished.

7“The Experience,” press release, SFAI, May 23, 1966. SFAI Archives.

8Annie Leibovitz had been a student in Bruce Nauman’s sculpture class.

9Paul Kos, “Studio 10,” in San Francisco Art Institute MFA Catalog, 2002 (San Francisco: SFAI, 2002).

10Carol Szymanski, quoted in Taylor Dafoe, “‘I Fell in Love With Art There’: As the San Francisco Art Institute Closes, 5 Celebrated Artists Reflect on How the School Shaped Them,” Artnet News, April 1, 2020. Available online at https://news.artnet.com/art-world/san-francisco-art-institute-alumni-1820244 (accessed June 10, 2021).

11Barry McGee, quoted in “10 Famous Artists You Didn’t Know Went to SFAI,” (im)material Blog, SFAI, n.d. Available online at https://sfai.edu/blog/ten-famous-artists-who-went-to-sfai (accessed June 10, 2021).

12Leibovitz, quoted in Cynthia Robins, “Celebrities Wow Art Crowd,” San Francisco Examiner, March 18, 1996.

13Jane Reed, email to the author, April 9, 2021.

14Steve Anker, “Radicalizing Vision: Film and Video in the Schools,” in Anker, Kathy Geritz, and Steve Seid, eds., Radical Light: Alternative Film & Video in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945–2000 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2010), p. 155. This account was drawn from Anker’s essay, pp. 152–58.

15Kathryn Bigelow, quoted in “SFAI Alumna Spotlight: Kathryn Bigelow,” Art & Education, June 26, 2013. Available online at https://www.artandeducation.net/announcements/108449/sfai-alumna-spotlight-kathryn-bigelow (accessed June 10, 2021).

16Stephanie Syjuco, quoted in Dafoe, “‘I Fell in Love With Art There.’”

17Devendra Banhart, email to the author, April 20, 2021.

18A transcript of the conference is available online at https://www.ubu.com/historical/wrtma/transcript.htm (accessed June 10, 2021).

19The transcript is currently being digitized; see https://sfai.edu/press-releases/sfai-receives-prestigious-grant-to-digitize-recordings-featuring-some-of-the-most-prominent-names-in-20th-century-art-history (accessed June 24, 2021).

20Directors of the exhibition program over the years have included James Monte, Phil Linhares, Helene Fried, David Rubin, Richard Pinnegar, Jeanie Weiffenbach, Karen Moss, Hou Hanru, Andrew McClintock, Hesse McGraw, Katie Morgan, and Kat Trataris.

21Artists represented in American Primitive and Naïve Art were W. L. Caldwell, Carlos Carvajal Sr., Jim Colclough, Flipper, B. J. Newton, Harold Pedersen, Jane Porter, Martín Ramírez, Pauline Simon, P. M. Wentworth, and Joseph Yoakum.

22Obalil, telephone conversation with the author.

23A group of alumni, noting that fundraising outreach to alumni had virtually and inexplicably fallen off, have formed their own committee, SF Artists Alumni, to promote a collaborative way forward. They maintain and expand outreach to alumni all over the world and publish a newsletter covering alumni activities.

24See Zachary Small, “San Francisco’s Top Art School Says Future Hinges on a Diego Rivera Mural,” New York Times, January 5, 2021.

25See “San Francisco Art Institute Reviews,” Niche. Available online at https://www.niche.com/colleges/san-francisco-art-institute/reviews/ (accessed June 10, 2021).

26Dara Birnbaum, quoted in Dafoe, “‘I Fell in Love With Art There.’”

SFAI’s benefit auction and sale, Looking Forward, featuring works by Edward and Nancy Kienholz, Diane Arbus, Hans Hofmann, Hung Liu, Wayne Thiebaud, and William T. Wiley, among others, will take place at SFAI on November 4, 2021; to attend the event, purchase tickets at sfai.edu