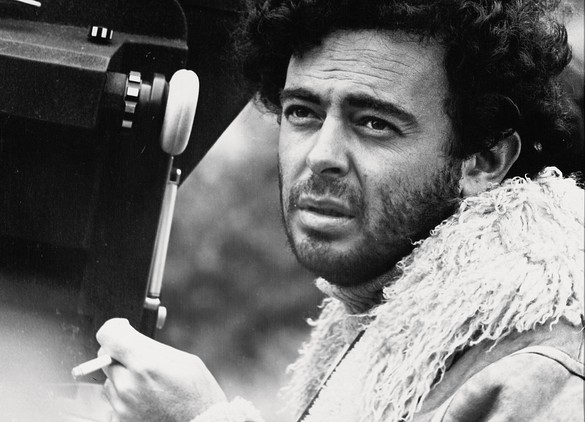

Carlos Valladares is a writer, critic, programmer, journalist, and video essayist from South Central Los Angeles, California. He studied film at Stanford University and began his PhD in History of Art and Film & Media Studies at Yale University in fall 2019. He has written for the San Francisco Chronicle, Film Comment, and the Criterion Collection. Photo: Jerry Schatzberg

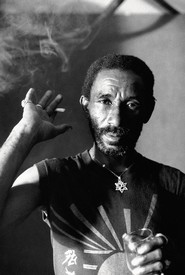

“Enough of criticizing cinema,” said Glauber Rocha in 1970. “We need to transform it.” Refusing to swallow the Enlightenment brand of reality that had been foisted on him and on Brazil, Rocha embraced his status as a Third World auteur—not an individualist loner working to hone a signature style but a dreamer of a people, of a world in a permanent state of maelstrom and trance.1 Combining Dada, surrealism, anarchy, mystical Trotskyism, candomblé, and the anthropophagic tropicalism of the modernist poet Oswald de Andrade, Rocha flummoxes, perverts, howls with freedom and despair. His major films—Barravento (The Turning Wind, 1962), Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol (Black God, White Devil, 1964),2 Terra em Transe (Entranced Earth, 1967), O Dragão da Maldade contra o Santo Guerreiro (Antonio Das Mortes, 1969),3 and A Idade da Terra (The Age of the Earth, 1980)—spark rebellion in the viewer, a desire to embrace the life of flux, fury, love, and unreason. The question for Rocha becomes not “What is reason?” but “Which unreason will win the war?”

In 1969, Rocha premiered Antonio Das Mortes at the Cannes Film Festival and won the best-director award. Only a few months earlier, Brazil’s military regime had suspended its citizens’ personal liberties and begun a brutal censorship of anything it deemed subversive. These conditions pushed Rocha into a decade of international exile; when he returned to Brazil during the “opening” of the country after 1977, he used his newfound optimism to create the glorious A Idade da Terra. Impelled by the murder of Pier Paolo Pasolini in 1975, he set out to respond to the Italian director’s masterpiece, The Gospel according to Matthew (1964), whose interpretation of Christ he praised as “the voice of the new morality: the morality of the conscious man in the developing world.”4 A Idade loosely follows the efforts of four Third World Christs (Indigenous, Black, guerrilla, and military) to stop a vulgar US industrialist from advancing into Brasília, the outsized modern capital of Brazil. Like all of Rocha’s great works, it is a total film of the future: opaque, lyrical, unstable, outrageous.

Rocha was one of the most brilliant critics in the history of film, as combative and insightful as Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Marie Straub, Dziga Vertov, and Sergei Eisenstein. He may even have more to teach us than those four, since his frame of reference included not only Europe and the United States but also Latin America and the Third World. If critics and producers mocked him out of confusion and fear, he commanded the respect of his fellow directors. After the disastrously received premiere of A Idade da Terra at the 1980 Venice Film Festival, one of the film’s only serious defenders was Michelangelo Antonioni, who wrote to Rocha, “Each scene is a lesson showing how modern cinema has to be done.”5

As a proponent of Brazil’s Cinema Novo, Rocha was determined to reflect Brazil back to itself in all its contradictions and all its capacity for crazy dreaming. “Therein lies the tragic originality of cinema novo in relation to world cinema: our originality is our hunger,” Rocha wrote, “and our greatest misery is that this hunger, while it’s felt, is not understood.”6 Since Rocha felt that Brazilians could not eat, he nourished them with his films while blocking the country’s enemies from sating their appetite for a culture that they could never understand or recolonize. He also confronted them with their own capacity for violence and brutality. And he gave the oppressed a new visual language with which to strike back, from serpentine long takes to shards of aggressive montage, all revealing how a reality that at first glance seemed coherent was illogical, intolerable, incomplete.

Rocha’s work is defined by rupture. A blast to the complacent psyche, it confronts you with your own political inadequacy, your inability to hide behind a stance of neutrality. Manny Farber once wrote of Godard, “No other filmmaker has so consistently made me feel like a stupid ass.”7 I feel the same with Glauber Rocha. Beneath his audiovisual foaming-of-the-mouth seethes a passion that leads him to rhapsodies in praise of dreams, love, a commitment to life’s mess. Anyone serious about cinema will surely toast Rocha as they return to his films and writings over the course of their lives.

1Horacio González writes that what Rocha meant by trance (transe) was “a state of convulsed wakefulness that assaulted the creative consciousness and provided its true impulse, guaranteeing that the work it produced would be independent of the spasms that originated it.” González, “Glauber Rocha’s Thinking: The Proximity of Memory,” in Glauber Rocha. Del hambre al sueño: obra, política y pensamiento/From Hunger to Dream: Work, Politics and Thought, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, 2004), p. 386.

2A literal translation of Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol would be “God and the devil in the land of the sun.” The film was released in the United States as Black God, White Devil.

3A literal translation of O Dragão da Maldade contra o Santo Guerreiro would be “The dragon of wickedness against the holy warrior.” In most countries the film was released as Antonio Das Mortes.

4Glauber Rocha, “The Morality of a New Christ,” in Glauber Rocha, On Cinema, ed. Ismail Xavier, trans. Stephanie Dennison and Charlotte Smith (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2019), p. 176.

5Michelangelo Antonioni, in Eduardo F. Costantini Jr., “Homage to a Thought in Trance,” in Glauber Rocha: From Hunger to Dream, p. 281.

6Glauber Rocha, “An Aesthetics of Hunger,” 1965, in Rocha, On Cinema, p. 43.

7Manny Farber, “Jean-Luc Godard,” in Farber on Film: The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber (New York: Library of America, 2009), p. 633.