David Rimanelli began writing about art in 1988 and has chronicled developments in the New York art world for over two decades. From 1993 to 1999, he was a regular contributor to The New Yorker; since 1997 he has been a contributing editor at Artforum, writing also for Bookforum, Interview, Texte zur Kunst, Vogue Paris, frieze, The New York Times, and Flash Art.

Jeff Wall was born in 1946 in Vancouver, Canada, where he continues to live and work. He has exhibited widely, including solo exhibitions at Tate Modern, London (2005), the Museum of Modern Art, New York/Art Institute of Chicago/San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2007), the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam/Kunsthaus Bregenz (2014), and the Kunsthalle Mannheim, Germany (2018). Photo: Miro Kuzmanovic

David RimanelliJeff, do the photographs in this exhibition work together as a group, either thematically or conceptually? You’ve returned throughout your career to subjects that could be labeled as landscapes, interiors, and allegories. How do you characterize this exhibition’s iteration of those modes?

Jeff WallI don’t make exhibitions as such—each picture is a singular event, I never aim to make a picture that relates to another one in any deliberate way—but sometimes affinities show up later. In this show there could be a few connections. Half of the exhibition, including some of the older pieces we’re including, are exteriors or landscapes. There are The Gardens [2017] and Hillside Sicily, November 2007 [2007], which was done more than ten years ago but has rarely been seen in New York, as well as Daybreak [2011], the picture made in Israel, and the recent picture Recovery [2017–18], which is set in a seaside park in summertime. They’re generically related to each other because of the wide view, the exteriority, the weather, the places, the light.

And then there’s the other group of pictures, some of them interiors, some exteriors but not really landscapes. There’s a little girl lying on the sidewalk in Parent child [2018], and, by coincidence, there’s another picture with a little girl in it. Is that a theme? It almost feels like one in the context of the show; there are crossings-over that happen, but they weren’t planned.

DRWhen I look at the images in the show, I start to narrativize them. I think viewers of the exhibition will make connections even if you didn’t intend them. Don’t you think?

JWYes, it’s inherent in the experience of seeing pictures that one does that.

DRYou haven’t used the lightbox medium for over a decade. Were you tired of it? Was there a desire to make photographs in a more reticent or “traditional” vein?

JWI was tired of the lightbox, in part for technical reasons. Photographing for that transmission of light has specific requirements that I began to feel were restrictive. I also found that I was becoming less satisfied with the emphatic presence of the work of that kind, especially in relation to other things around it in exhibitions.

DRSome of your earlier work has this somewhat hortatory presence. I’m thinking of Picture for Women [1979], which has an almost peremptory quality of address: “Listen to me. Look at me.” I think this made them very exciting and alive at that time, but I can see how speaking in this kind of stentorian tone could become less interesting for an artist.

JWThe images themselves often didn’t do that, but the medium did, or at least it went in that direction. I have more than one tone of voice, as you put it, and I wanted to hear what some of the others sounded like. Also, obviously, photography is more expansive than any one type of print could encompass. I began to work in black-and-white about twenty years ago because I wanted to have a larger repertoire. And then the arrival of inkjet printers around 2000 changed the way color photographs were going to be made—the technology presented an attractive opening for another kind of color photography.

DRSo in the last fifteen years your work has moved away from the lightbox and has become less hortatory. That seems very much the case with the photographs in this exhibition. The one that seems to evoke that earlier phase of your work would be the diptych Summer Afternoons, from 2013. With its high saturation, the nude man, the composition, it reminds me of Stereo [1980]. Could you speak to that a little?

JW That’s interesting—I hadn’t thought of it, but it does resemble Stereo. In general I don’t think the subject matter of my pictures has changed in character all that much. Stereo is a good example, because the reclining man in that photograph—which was made almost forty years ago!—isn’t really much different in mood or composition from the man in Summer Afternoons. I’m older now, so I see things differently, I guess, but aside from that, I’ve always felt that there’s continuity. I don’t know whether I could change—I’m not sure what that would mean, because picture-making is so free but also so highly structured by our tradition that pictures tend to resemble each other when they’re made in certain ways.

Summer Afternoons was based on a couple of personal memories of a particular place, which was a replica of a real place I once lived in. Its character came back to me and that meaning or mood was worth investigating. The nudes came, in a way, out of the bright warmth of that place. The fact that they emerged as a kind of outcome of something else is typical of what I’ve done for a long time. The figures appearing in my photographs are phantoms, in a way, that have emerged out of a set of circumstances that gave rise to that motif. They’re hard to explain but they happen, and sometimes those figures have a kind of emblematic quality.

DRThe male figure in particular has a sort of Matissean quality.

JWI wouldn’t have thought of it directly at the time, but yes, Matisse is a big favorite and his color sense is obviously a model for how to do color in painting, color in anything for that matter. The color was also informed by the work of the English interior decorator David Hicks. My wife Jeannette likes his work so much, and she helped me with the decor. She painted that London flat those colors in 1972. I recreated it using our old photographs. All of those elements are part of a language that engages what I’m trying to do, which is basically to make a picture in our tradition, such as it exists today.

The figures appearing in my photographs are phantoms, in a way . . .

Jeff Wall

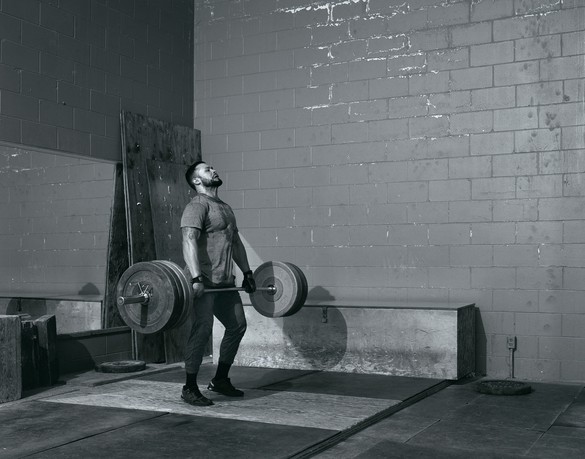

DRI’d like to talk about your black-and-white pictures. You’ve spoken about the palpable, physical qualities of black-and-white photography. This characterization is so incredibly powerful and clear in Weightlifter [2015]: there’s the rich gradations of gray, black, silver, the reflection of the metal. It’s very physical. This physicality of the material is echoed in the subject itself. For me, as a viewer of the picture, it’s filled with sexuality. Am I wrong to read it this way?

JWI don’t think you can have a human figure in a picture without that erotic element being present. It’s simply part of the picturing effect, because people do relate to people in pictures as if they were beings. It’s just one of the great pleasures of aesthetic experience—this “as if” experience of another person. We can never extract that erotic dimension from any aesthetic experience. So, of course, you’re completely right. And it makes no difference what I intended because I’m not sure I really know or even care to know what I really intended, except to make a picture of a weightlifter and do it as well as I could. The rest takes off on its own. As I’ve said many times, the viewer writes the poem that the artist has erased in the process of making the picture. I don’t think eroticism in art has anything to do with erotic subject matter directly.

DRThat’s an unconventional idea.

JWMatisse is a great example here as well, where his swirl of color and shape is erotic and exciting on its own, whether it’s a tree or a sky or a face. I think all picture-making has that in it to different degrees.

Back to the question of the physicality of black-and-white photographs: yes, there’s something luxurious and yet austere about the monochrome element. I feel that the vanishing of color is itself exciting. You know there are colors there but you can’t see them. That’s an excitement that’s always been there in black-and-white photography. It creates a real physical effect.

But of course the inkjet print is, in fact, just as physical. My friend Roy Arden says inkjet prints are machine-made pointillist paintings; like Seurat’s pictures, they’re made of dots. The dots are just smaller and made by a machine.

DRWhen I interviewed you once many years ago, I remember you told me that you weren’t interested in popular culture. It was such a striking thing to say, because it seemed so out of step with what people think contemporary art is supposed to be interested in or about. It struck me as very much like the avant-garde in a way, this refusal, this saying “No. No popular culture. No.”

JWI think it’s saying no to conventionality more than to popular culture. That all artists somehow express their relation to the culture they emerged from is obviously true, but the new conventional assumption over the last twenty, thirty years is that all recent artists have emerged from a background primarily shaped by mass culture. That’s not true for me, partly because I’m older. My own childhood and adolescence weren’t marked very much by popular culture; I was interested in high culture, so called, then—novels and paintings and so on—much more than in popular forms, even though I’m perfectly aware of them. I can’t be that absorbed in popular culture partly because I didn’t have those childhood passions, and also because I’m just more affected by older forms and attitudes that don’t derive from the mass-cultural norm.

DRIt wouldn’t be authentic.

JWYes, so I have a critical view of the conventionality of the attitude toward the relation between popular culture and serious art. It’s become what’s expected of artists—to define themselves in relation to their emergence from popular culture, mass culture, subcultures. This implies that not doing so is somehow an obsolete way of being an artist. By now, the idea that art essentially or primarily emerges from the artist’s childhood relation with mass-culture forms is so conventional it’s become tiresome.

DRBanal.

JWYes. Traces of mass-culture forms appear in my pictures because I can’t avoid them. But these elements are part of the actuality, part of the landscape; they needn’t be excised.

DRIt’s not the motive of the work.

JWNo, but I have to accept the world. I’m a photographer; I have to accept what appears as it appears.

Artwork © Jeff Wall; interview conducted on the occasion of Jeff Wall, Gagosian, New York, April 30–July 26, 2019