Sir David Adjaye OBE is a Ghanaian-British architect who has received international acclaim. In 2000, he founded Adjaye Associates, which today maintains studios in Accra, London, and New York and runs projects spanning the globe. Born in Tanzania to Ghanaian parents, Adjaye has established himself as an architect with an artist’s sensibility and vision. He is known for his ingenious use of materials and his sculptural ability and his influences range from contemporary art, music, and science to African art forms and the life of cities. His projects range from private houses, bespoke furniture collections, product design, exhibitions, and temporary pavilions to arts centers, civic buildings, and master plans.

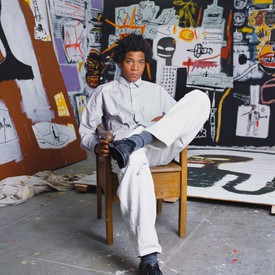

Sumayya Vally is the principal of Counterspace, a Johannesburg-based architecture and research studio. In London she designed the Serpentine Pavilion for 2021, the youngest architect ever invited to participate in this twenty-year annual program, and she initiated and developed the Serpentine’s Support Structures for Support Structures program, which supports and connects artists working at the intersections of arts and ecology, arts and social justice, and arts and the archive.

Sumayya VallyDavid, I believe our first real connection was when I came to London to interview you and we had a very discursive conversation about the future of architectural practice in Johannesburg and in Africa, which was very meaningful for me. I feel lucky that we were able to reconnect two years later through the Serpentine Pavilion, where the firm I direct, Counterspace, presented earlier this year.

David AdjayeYes, I remember that interview; it felt like twenty minutes but it was actually like fifty. That’s usually how it works when you find somebody whom you have a kindred relationship to. It was obvious to me then that you were somebody who was just waiting to arrive on the world stage. I didn’t feel like you were my mentee at that time, because I knew you were already at the next level.

SVThank you, David. I think I was young and in a very different space at that time, but I felt very grateful for those conversations. It was a special energy, particularly because we spoke so seriously about the future of architectural practice on the African continent.

DAYes, that’s something that was immediately binding. As you know, it’s an important issue for me. Hopefully we’re now starting to accelerate toward putting into place a serious piece of infrastructure that could start to add to that idea of education and practice on the continent.

But here we are again, the universe collides, and now we’re doing a show, Social Works II, with Antwaun [Sargent] at Gagosian, London. It’s really an opportunity to look toward new practices. We’re the odd ones out in the sense that we’re architects—or, as I like to say, we’re form-makers in the world, whatever manner that takes on. In the context of this show, we’re working with what I call “fragments,” ideas not necessarily about things that are going into the built environment. Social Works II is a fascinating space that allows experimentation to happen in a way that traditional architectural practice can’t afford, since the business of architecture necessitates something rather closed, don’t you think?

SVYes, but I think that’s the business of architecture as we know it now. I’ve found it interesting that you don’t care to define yourself as an architect per se. I really consider myself an architect and always introduce myself as such, because I believe so much in starting to rethink and expand what the definition of an architect can be, particularly for our context. So many of the traditions of form-making that we have fall short of what architecture could be or needs to be for the continent and for our context.

DAThat makes a lot of sense. We’re in very different places: for you that’s a critical definition because you’re becoming, and I’m not in that space. Both things are relevant and it’s really about time. I wouldn’t have engaged in this way in an exhibition like this early in my career. Your interest in doing it early on speaks to what you just said about wanting to define how you see architectural practice.

I’d love to hear about the work you’ll be showing in Social Works II.

SVIt’s changing and evolving as we speak. To describe it generally, the piece is a set of ritual fragments that form a solid wall, but each of the fragments can be unpacked into the space and I see each of them as a catalyst for creating rituals, not only in the gallery but also, I hope, outside of it. The idea is that they will move outside the gallery, pick up resonance from other places, and then potentially return for a series of gatherings within the gallery as well. All of the fragments are abstractions of ritual objects, which I see as a continuation of the Serpentine Pavilion. They come from traditions of faith, and all of them, despite being very small, by implication have very large gestures. The idea is to create this wall in the gallery that starts out as solid but becomes more porous over time.

DASo these fragments are to be used?

SVYes, we’ll be holding a series of gatherings around each object. The forms are pieces of ritual architectures that will then host and hold rituals. Does that make sense?

DAIt makes a lot of sense.

SVI’m thinking about first launching one piece, then constructing the remaining parts over time. I think it will be better if it’s periodic as opposed to starting out whole. It also works with the logic of how the pieces move that they accrete over time and involve a process of exchange.

DAThe work is part of an evolution. There’s something about the uniqueness of a work like that that I think is powerful.

SVYes, I think maybe we also then use this first opportunity with the work to be able to attest to its use, and let the ritual functions grow and develop, and have a conversation with what the form needs to be, so that it really does become a platform for research and experimentation. It’s an opportunity that’s so generous, especially for our profession.

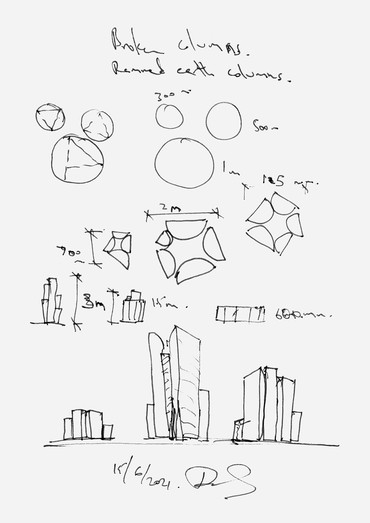

DAExactly. After the first iteration of Social Works in New York, Antwaun asked me to also take part in London because of my relationship to the city. I wanted to continue the research that I began with the large-scale sculpture, Asaase, that I made for New York. My current preoccupation is a rethinking of earth and/or our relationship to earth, and what that means. For me, how to return the artifice of architecture to the geology of the planet, and to create less industrialization and more craft in the process of making buildings, is a key inquiry, a constant questioning and search.

With Social Works I also wanted to discuss memory and the physical matter of place. If Asaase was romantic in the sense that it was about the United States and the memory of Africa, a transatlantic dialogue, in London I’m interested in the phenomena of the island of the United Kingdom and this very specific place. It’s a much more reduced piece that really almost extracts out of the earth, as if you could syringe out of the earth a sort of core of earth and remix it into something newly solid. It started off as a single column, but I decided to bisect it and to create a composition. And as it’s evolved, it’s become a column that’s divided into five pieces, and the five pieces create a new arrangement as a kind of new column that’s no longer really behaving like a column but as a kind of composition. It allows viewers to see the soil and its nature in different geometric compressions and expansions, and to see it as a sort of artifact of the idea of form. In this way, it’s almost a diametrically opposite game to the first installation, which isn’t surprising since it’s speaking to a different context, which is: What is England, and where are we, and what is making?

SVI really like this critical, and also playful, take on the politics of land and earth. And I enjoy very much that it’s so different from the first one, which had a kind of longing. This is beautiful and critical in a very different way. I often talk about my project being tied to earth and place, but I think I often imagine that as being about grounding practices and how architecture gives form to them. You’re talking very directly about earth and matter and the material of a place, which is so interesting in London, especially because of how densely centered it is as the heart of a once-industrial empire. It also means that there’s earth there from everywhere else, in a way, because of how the colonies functioned.

DAI hope it provokes that dialogue, absolutely. Also, in any city that becomes metropolitan, there’s a widespread forgetting of the earth. Even though there are many parks, they’re ultimately filled with the artifice of grass; it’s not the grass of the earth, which is the most abundant plant on the earth, it’s a species that we’ve edited and created as a singular monoculture. So we actually still don’t really see the earth. I’m less interested in this idea of controlling nature and more interested in our corelationship with nature. Even though the geometries can be abstract, the visceral emotion is very direct. In fact that duality is important to me—it’s not a pile of earth, it’s a form of earth.

SVI think land is an archive of place, the way it’s been shifted and what it contains, how toxic it is. All of these layers tell us something about the story of movement on that land, which also speaks to the fact that we’re so deeply connected to land in our bodies and in our DNA. That’s something we keep returning to in South Africa.

DAOn the African continent, the presence of land is much more clear, because the development of the cities has simply not created a complete art, or an Anthropocene sort of erasure and pure control of nature. So the disruption that some people call underdevelopment I now realize is actually profound beauty.

Social Works II: Curated by Antwaun Sargent, Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill, London, October 7–December 18, 2021

The “Social Works II” supplement also includes: “Tyler Mitchell: A New Landscape”; “Amanda Williams: What Black is This”; poetry by Raymond Antrobus and Caleb Femi; “Kahlil Robert Irving”; and “Manuel Mathieu: The Delusion of Power”