Jessica Beck is a director at Gagosian, Beverly Hills. Beck was formerly the Milton Fine Curator of Art at the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh. She has curated many projects, most notably Andy Warhol: My Perfect Body, the first exhibition to explore the complexities of the body, through beauty, pain, and perfection, in Warhol’s practice. Photo: Abby Warhola

Jessica BeckHello, Christopher. So we’re here in your new studio space, where you just moved in two years ago. Where should we start?

Christopher MakosWith the bike ride today.

JBYeah. [Laughs.]

CMI suggested that you take your first bike ride ever in Manhattan, and so we biked from Eighteenth to Twenty-Ninth Street. What did you think of it?

JBIt was wonderful and playful and unexpected. And I feel like that’s how you were with Warhol, maybe?

CMEverything was unexpected, because Andy never knew what to expect with me. That’s why we were such good pals. He would often say, I wish we could take your energy and put it in a bottle, and then we’d sell it, the Chris Makos energy.

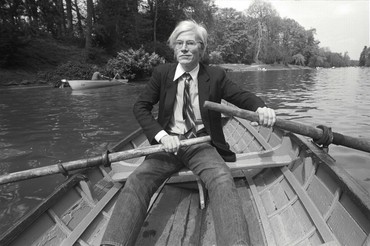

JBDid you go bike riding with him ever?

CMAndy would have loved to go bike riding but didn’t really have that, so I have that really cool picture of him holding my bike, looking like he’s getting ready to bicycle. Not unlike that picture of Andy in Denver, Colorado. He had bought land there and we were out at the airport with John Denver. John was showing him one of his experimental biplanes. I said, “Get in.” But it was too hard to do, so I said, “Stand on the other side.” I took it so it looked like he’s in the plane. Like so many of my photographs, it was kind of set up.

JBThe thing that’s so interesting about how you photographed Warhol is that it was often playful, or you posed him in a way. How did that work between you?

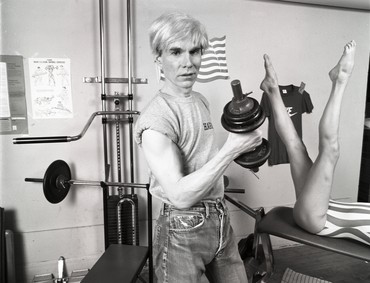

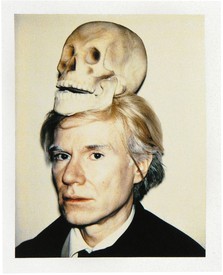

CMWell, he ended up being my muse. Because here’s a guy who came from Pittsburgh, never really had the look of all the other boys, was never athletic—he always wanted to be one of the guys and never could be, and he ended up being one of the guys with me. So however that translated itself—posing in front of an airplane, pretending to be on a bike . . . Toward the end, though, he was physically fit; there’s that picture of him with his muscles and Lydia, his trainer.

But in all of my portraits, even in my most recent book, Warhol Modeling Portfolio, the poses are the most unbelievably awkward, peculiar poses you could ever imagine. Unlike photographers who want to manipulate the subject, I like to put people in a place with good lighting and then let them go and see where they take us. And Andy often took me and him to the most oddball places as far as posing. In the pictures in London, look at his hands. He was an artist. He painted. Two things you might notice: His hands were perfectly manicured, something I never realized until I started looking at the pictures closely. And then look at the gestures. He didn’t know what to do with his hands, so there are all these extremely oddball poses, which in the beginning were oddball and now, just like architecture, have aged well.

JBThe photograph of him weightlifting with Lydia, the trainer, behind him—was that for a television episode?

CMNo, it was a separate thing. If you’re familiar with the layout of 860 Broadway [the Factory], there was the main room and then there was a back area where he painted and did all the piss paintings. And that’s where his faux gym was set up, and that’s where Lydia would come. I would come and work out with him a little bit too.

JBSo the image of him weightlifting, he’s just posing for you—

CMYeah. It wasn’t just happenstance. We said, I’m coming tomorrow, get your T-shirt out.

JBEveryone thinks that the legs in the background of that photo are fake when they first see it.

CMOh, really?

JBBecause they’re so toned and perfectly in the air—

CMIt’s so corny, isn’t it? [Laughs.]

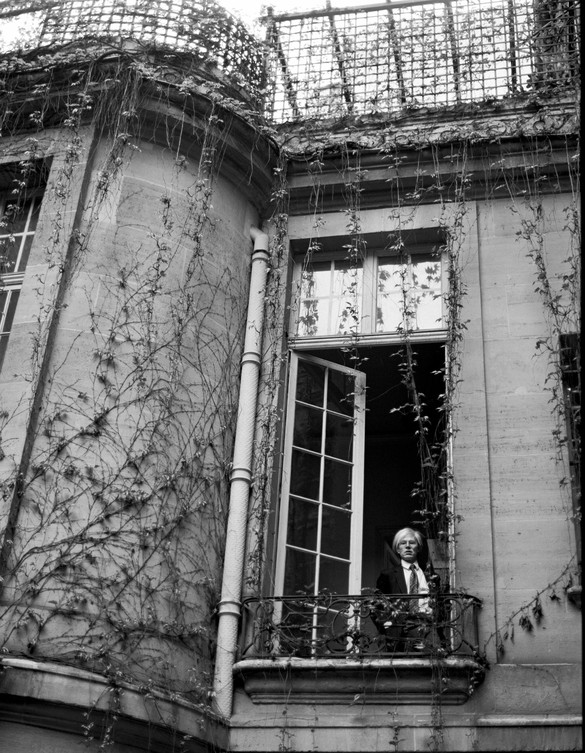

JBIt’s actually amazing, though. There is also a photo of him in Paris that we have in the exhibition, of him outside the door in Paris—

CMOh yeah, that’s his apartment on rue du Cherche-Midi. Whenever people go to Paris, I say, This is a fun thing to do: Go to number sixteen rue du Cherche-Midi. That’s the doorway to Andy’s apartment. His apartment was in the back. Across the street from that is a place called Poilâne. That was his favorite place to have apple tarts and nut bread. They had the best apple tarts in the world. Down the street was Le Cherche Midi, which is this French-Italian bistro where it’s all handmade pastas. Unbelievable. And then just around the corner, on boulevard Saint-Germain, is Café de Flore, where we would have afternoon tea, and across the street was Brasserie Lipp. That’s a whole little Warhol tour that one could do. And then over on rue Saint-Honoré was the Geurlain perfume shop; he loved to go in there and buy Geurlain just for the bottles. He loved to collect perfume bottles.

JBHow often did he go to Paris?

CMWe would go to Paris as a stop-off point to go to Germany, because at that time the Concorde was operating, so we’d go New York to Paris in four hours and go to his apartment. He loved to go shopping and look at stuff, collect stuff. And then we’d go on to Germany, usually to Bonn. Can you imagine? I have a picture of us on a Lufthansa plane. I keep telling people, Can’t we use my photographs as the script and you can just do the movie like that? Because I have all of that, you know?

JBYeah, because you traveled a lot with him.

CMRight. Those were really wonderful, crazy moments.

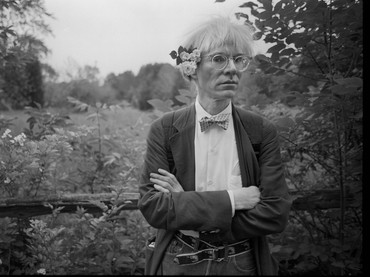

JBYou also have these great photos of him at [Philip Johnson’s] Glass House, and they’re so sweet, and soft. There are images of him with a flower behind his ear. I’m wondering, were there specific moments when something was staged?

CMEverything was staged. What I mean is we’d find ourselves in a situation and I’d say, Wow, just get over there, do this, pose for me. Because I didn’t know what else to do. I couldn’t talk the art talk. But what I could do is find my friend in oddball places, and I had my camera.

Andy and I always had fun. The basis of our photos, which still to this day look alive and lively, is our admiration for each other, who we were, and having fun.

JBAt the end of The Andy Warhol Diaries, the documentary for Netflix, are these beautiful archival moments of you with Warhol in Milan, with all the press for The Last Supper and you traveling with him, and then a voiceover reading from Warhol’s diaries saying, “I loved having Christopher around. He was always so much fun. He was so sweet and he was so great to travel with.”

CMSuch a nice endorsement, right?

JBYeah. [Laughs.] But also, it was just so great to see you in that moment, at that time, and being a little protective of Warhol too.

CMWell, after a while it got so out of hand, kind of like the world that the Kardashians and Meghan Markle and all those people go through. You know, in Warhol shows the one thing that’s never captured is the hysteria around him. If you ever do another show, you should have the entrance room kind of dark; people walk in and there are thousands of flashbulbs and then you leave that room and then you see the show. Because that was what was going on with Andy anywhere he went.

JBDid he ever shut down around all of that? Did that make him nervous, especially after he was shot?

CMNo, not terribly. You have to remember, he always loved being around movie stars. He loved that whole thing. To finally be a star in that Hollywood way, he liked it. When we were on the book tour for America [1985], that was packed everywhere.

JBThat was the book tour when someone took his wig.

CMYeah. I wasn’t there. I was happy I wasn’t because I would have been really appalled. How disgusting.

JBThe way it’s written in the diaries is so vivid—someone came, grabbed the wig, threw it over a balcony, and he says it was like he was shot again. He immediately put something over his head to cover it because he was so embarrassed.

CMI guess the lesson learned is always carry a spare. [Laughter.] Just keep it in your pocket. My favorite story about the wigs is that he would buy them and then go to haircutters and have them cut by barbers. I love that. You know, it says a lot about the human spirit that no matter what happens to us, we adjust. He was shot and he made it through, and he adjusted.

JBWhat I love about your contribution to Warhol’s legacy is the levity and playfulness that you bring to the narrative. You remind us all of Warhol’s humanness, and reveal his sweeter, softer side. Thank you for that, and thank you for speaking with me.

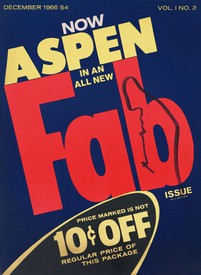

Andy Warhol’s Insiders, Gagosian Shop, London, May 25–July 29, 2023

Artwork © Christopher Makos