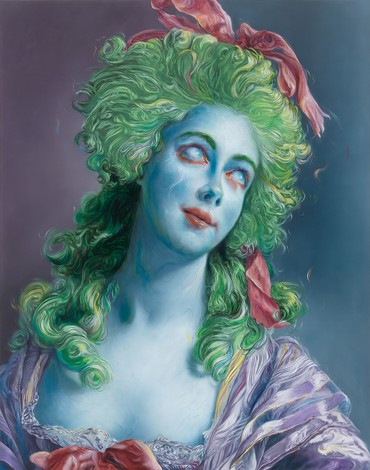

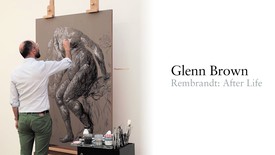

Mining art history and popular culture, Glenn Brown has created an artistic language that transcends time and pictorial conventions. His mannerist impulses stem from a desire to breathe new life into the extremities of historical form. Through reference, appropriation, and investigation, he presents a contemporary reading of images new and remembered. Photo: Edgar Laguinia

Born in London, Hari Kunzru is the author of the novels The Impressionist, Transmission, My Revolutions, and Gods Without Men, as well as a short story collection, Noise, and a novella, Memory Palace. His novel White Tears was published in spring 2017. He was a 2008 Cullman Fellow at the New York Public Library, a 2014 Guggenheim Fellow, and a 2016 Fellow of the American Academy in Berlin. He lives in New York City. Photo: Clayton Cubitt

Hari KunzruYour work always has some kind of context or response; it jumps off from something else. It’s interesting to me that visually you always start with something, like a preexisting frame or source material.

Glenn BrownYes, I’m using preexisting images to go into preexisting frames. I’m using the frame as a readymade, and the images I use as a starting point. I don’t like a blank canvas or a blank sheet of paper, I want context. There’s a long tradition of artists sitting in front of a model, a sitter, a landscape, or a still life, and painting or drawing. I sometimes think of myself as standing behind them whilst working, asking, “Why did you do that?” “What does this work do?” “What would happen if you used a different palette, like this Turner painting, or Kirchner, or Baselitz?” I have a constant chatter of ideas from throughout the history of art. This world we live in is so man-made, nature has been banished to the land of kitsch, whether we like it or not. I suppose I’m trying to make art for our man-made world, for a deconstructed audience. I want to be an eternal student, always learning.

HKIn my line of work, I like to walk back, to step away. Eventually I stop tinkering, when there’s a sense that I can’t or shouldn’t do any more, but it’s never totally clear when something is finished; if given the chance, I’ll touch it up again. Is that true for you as well?

GBYes, that final editing can carry on for a long time. Sometimes it feels more like I’m giving up than declaring it finished. I often just don’t see any more that I can do, therefore I go and look at more art to find out how other people resolved similar problems. There’s no such thing as a perfect painting. Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon—it’s very unresolved. He made so many problems for himself that there was no hope of solving everything.

HKAt some point it’s probably best to step away and start another one.

GBYes. I like to have paintings fester a bit before coming back to them, sometimes for years. Then maybe I might figure out what’s wrong with them.

HKCould you tell me more about how you know a work isn’t finished? Is there a set of procedures that you want to do to that picture [points to They Slipped the Surly Bonds of Earth and Touched the Face of God] in order to finish it, or is it more in the nature of problem solving?

GBAll I can say is that this painting doesn’t have enough life yet. There is a point in painting when a work gets a certain attitude, one that is slightly separate from mine—that’s when it comes alive. The painting starts to talk back to me to tell me what to do—that’s when it surprises me. One small brushstroke and then it’s immediately clear that the painting has a life of its own. In that way I presume it’s a bit like creating a character in one of your novels.

HKThere has to be something pleasing and surprising about seeing a thing that somehow exceeds the structure you created or your deliberate intentions in making it.

GBIt’s good not to be too conscious of all the decisions one’s brain makes, to let the subconscious make some of the decisions and to let the spirit of dead artists flow through me.

HKIt looks like sometimes you work on several versions or variations of a single image?

GBThese three paintings [Poor Art, Unknown Pleasures, They Slipped the Surly Bonds of Earth and Touched the Face of God] were made for a show at the Rembrandthuis in Amsterdam in 2017. My paintings are based on a portrait of Rembrandt, though almost certainly not by Rembrandt—a student of Rembrandt probably made the painting in the studio with Rembrandt’s supervision. My three paintings did not have the benefit of his expert supervision so things all got a bit strange. I loved that exhibition—that dialogue with his studio, in his studio. I couldn’t say all I wanted in one painting, so I made three. I liked the obsessive nature of the reproduction.

HKThere’s a horizontal band in the image—

GBThe bands changed color several times. On two versions it’s black, the only black in the paintings. This one has dark red.

HKIs that something you’ve done on other pictures?

GBOn other paintings I’ve placed similar flat bands of color, sometimes down the sides, like a Barnett Newman zip, as well as triangular bands in the corners in homage to Sigmar Polke. These are bits of modernism that float in and out of my fantasy world, like a Kandinsky abstract landscape. It’s really only a simple compositional device. Van Dyck and Titian employed similar devices. It’s a windowsill; he’s either leaning into your house or leaning out of his. Either way you’re not sure if you welcome the visit. It makes him more of a nuisance.

HKThe scale of your drawings can be surprising. There were works on paper that you’d done at a smaller scale, but now I see them painted and they’re actually quite large.

GBI like playing with scale. The intimacy one gets when peering at a small drawing and entering the delicate world of the artist is very special. The human hand is capable of extraordinarily delicate maneuvers. It’s a very special thing. Drawing and handwriting are things a contemporary audience isn’t used to anymore. It’s a celebration of the hand and its connection to the brain, just as the larger drawings use the wrist, the arm, and the body to make them. I’m always after the perfect exquisite mark. The paintings fetishize the brushmark and the drawings the pen or pencil line, so the line is both real and fake, genuine and ironic.

HKYou don’t underdraw or anything like that on the paintings?

GBI’m of the school of Gerhard Richter and photorealism, I suppose. Richter does no drawing, it’s just a reference to the photograph, and I came out of that background. But at some point I shifted to being far more interested in painting than I was in the conceptual idea of painting and photography and their relationship. And becoming more interested in painting, I realized there was a big hole in my work, and that was drawing. Drawing is the skeleton that holds the composition of any painting together, and I wasn’t really tackling it head on. So for two and a half years I didn’t do any painting, I just drew. I just wanted to use pure line.

HKIs it true that you refer to reproductions to serve as the color for your paintings?

GBYes, because the colors often shift in nice ways. I have books on Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Kees van Dongen, or Vincent van Gogh, for example, and I’ll look at perhaps six different reproductions of the same painting before I choose the one that I think best fits what I wanted to say. Typically that has nothing to do with the accuracy of the reproduction to the original work of art. Very often it’s a book from the 1970s or ’80s, where the color has shifted over time—I find the way colors shift rather interesting.

HKThen there’s that sort of Entartete Kunst thing: the thing that offended the Nazis so much was the, what would you call it, the damage, the disrespect, to the human of deciding to paint a face blue or green. It seems almost like there’s something of that in what you’re doing, and you were referring to Kirchner.

GBYes. Color shifts in reproduction but I embrace further color shifts—the further degradation of the human body interests me. Kirchner is a fantastic example. He was depicting the Berlin of his time, when the streets were gas lit and people were going out and promenading at night. The gas lamps gave everything this greenish-yellowish glow, so Kirchner was painting what was there—people looking this ghastly color because of the street lamps. There are a few places in London that still have gas lamps and they give off a different color than the modern halogens. It’s fascinating the way Kirchner was just accentuating what he was seeing. What he could see were prostitutes able to sell their wares at night in the streets, and men and women able to wear their finest clothes out at night as they walked in this ghastly dream world. These gas lamps merge into the gas used in the trenches of the First World War.

HKYou’re interested in image reproduction, and in questions about what painting does after the invention of photography. As you’ve progressed, you’ve become more of a painter rather than somebody using paints to engage with image-making more generally. We live in a world that already has lots of reproductions and lots of techniques for making pictures.

GBYes, one of my big influences was Sherrie Levine, who takes a very conceptual view of art history. Twenty years ago I was making photorealist paintings based on expressionist paintings. Then later I shifted to photorealist versions of photorealist or Surrealist or even science fiction paintings, which was sort of like hyperrealism.

HKSo your early works started with ideas from the Pictures generation, those gestures about the reproduction and the copy, questioning what’s the original. Where does science fiction come in? As someone who spent a lot of teenage time staring at reproductions on science fiction book covers and album covers and imagining this sublime other world, that’s interesting to me. I’m also interested in the techniques and visual terms of the way those airbrush pictures are done—I loved the seeming reality and perfectionism and the awesomeness of motherships flying. That seems to come from a slightly different place.

GBFor me it came directly out of a conversation I had with Michael Craig-Martin when I was a student. I’d been making these paintings after Frank Auerbach and Karel Appel, and Michael said, “That’s all very interesting but where else can you take it? What’s the logical conclusion? How far can you take the idea of painting paint? Of making a pointless photorealist painting?” We came to the conclusion together, “What about doing a photorealist painting of a photorealist painting?” That makes it conceptually rigorous, but pointless in every other way. I couldn’t quite bear to do that, because I had certain vestiges of being an artist and painter; I couldn’t be conceptual in the way Sherrie Levine or Pictures-generation artists could have. And after several months I decided that I couldn’t do a photorealist version of Richard Estes, where you couldn’t see the difference between the Richard Estes and mine. Estes is my favorite photorealist because he depicted Americana in a really rather wonderful way, and added gesture to photography. His paintings weren’t just painted photographs, he would pick certain elements out and ignore others and sharpen things up. So I came to the conclusion, why not do photorealist paintings of Surrealist paintings? Salvador Dalí was depicting his dreams—the work is meant to be reality, but a reality we can’t see. Science fiction images are like Surrealism in that way, they’re a dreamed reality but rendered in a way that’s meant to be realist. It was a more interesting take on the conceptual copy. The proliferation of science fiction and the fantasy worlds it has fed us changed the way we dream and paint. The first Dalí painting I made was painted upside down, not predrawing anything, so it became squashed and altered.

HKIt’s your translation of it.

GBYes, at the end I had too much space left so the head became enlarged. Inverting the image forced me to think about it in new ways.

HKIs that something you’ve experimented with a lot since? Elements that are translated through some sort of rotation? Maybe everybody looks a bit more like an El Greco painting than they started off in the original?

GBYes. It’s the El Greco effect, or the Modigliani effect, or the Giacometti effect. Elongating the human figure creates certain feelings of empathy, I suppose. I want the figure to distort, to be nonclassical, to be mannerist, and the distorted copy was my way of describing this.

HKI understand your interest in the copy, especially at this point in the history of image-making. And as you said, there’s an absurdity about the labor that goes into making a photorealist copy, which brings up all sorts of stuff. And the first time around the distortion was accidental, you allowed that to happen. But what’s the interest in continuing to make those distortions?

GBEverything I made after those first few paintings was not meant to look at all like the original. From that point on, there were always differences—I’d elongate. I’d change the color. I’d change elements of the background. I’d bind images together. I’d take a background from one image and a foreground from another and a color from a third. I’d often make up brush marks. I didn’t want the thing to look like the original—it had to bear a resemblance, but that was all. So that was a shift toward painting, and toward making something that was not just well composed because the original was well composed, but well composed because I’d decided it was well composed. There were decisions being made—I had to make sure the way your eye moved over the canvas was specific, tight, rigorous, interesting, and entertaining. That’s why I had to take control of the drawing.

HKIs there a utopian dimension to what you do?

GBI would say dystopian.

HKWell, yes, there’s quite a lot of both suffering and transcendence.

GBThat’s probably because the more you look at painting and at the history of Western art, the more you come across religion. I look a lot at the whole history of Western art, and religion seeps into everything. Of course many artists tried to find ways of getting around religious themes, tried to create something more interesting than the set agendas prescribed by religious benefactors, but they obviously had to feature them.

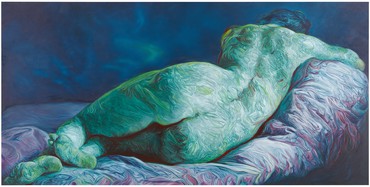

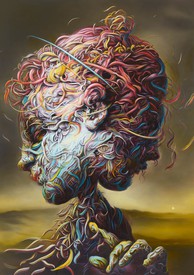

HKLet’s talk about the dystopian aspect. Something disturbing happens to the human figure in your work. I’ve been searching for language to describe it—there’s a sense of swarming and multiplicity and a kind of collapse of the individual. If you think of the classical depiction of the human body as noble and impermeable, a unified self, that seems to break down in your images.

GBI’ve come to the conclusion that all of us are in a controlled state of decay. We can do nothing about it and we should come to terms with it. That’s our mortality. Even starting in our early twenties, our bodies start to show signs of wear and tear and aging. As a society we need to deal with that, to cope with the fact that we’re decomposing and even to embrace it as a wonderful thing. The sense of the eternal is part of the decay.

HKWe are all made of stars.

GBYes, stardust.

HKAnd what about figures morphing into multiples?

GBThat comes from a postmodern idea that we’re made of languages, we’re not one person, we take on traits from other people, our identities can shift over time, nothing is set. We adapt according to our environment, and according to the language we think is appropriate to the environment we’re in. Even our bodies aren’t fixed: our skin is permeable. We are physically permeable just as our thoughts are permeable. Skin isn’t a solid, it’s translucent—

HKThe boundaries are fuzzy and porous and traversable.

GBYes. Our inner organs are more important than our outer ones, but we don’t always know that, or feel that.

HKAnd how do you feel about that? Does it scare you? Is it something to celebrate?

GBIt’s something to celebrate. It’s what we are as human beings; that’s amazing and should be celebrated. The scars of time on our bodies are beautiful. We’re like ants in a colony: no one individual is really that important. We like to think we are, because that’s how humans think, but fundamentally we live in colonies, we’re pack animals. We are replaceable. We’re just humans.

HKAre humans evolving? Are they becoming something else?

I want my paintings to be between states in every way you can think of, between beautiful and ugly, between violent and passive, between happy and sad, between male and female.

Glenn Brown

GBThe word “becoming” is sort of—is it [Gilles] Deleuze and [Félix] Guattari?

HKI’ve been trying to avoid using Deleuze and Guattari jargon the whole time [laughter].

GBA Thousand Plateaus was very important for me.

HKIt completely changed my life, to be honest. I’d bore the crap out of people by talking about it [laughter].

GBWell, I’m still living with the effects of it. That idea of becoming something, anything, that surrounds us, taking on information, taking on our environment—all that’s still there in my work. That’s why I appropriate images from other people: I get to become Rembrandt or Fragonard or van Gogh. I’m always in a state of becoming somebody else.

HKThat’s a very interesting way to think about your relationship to these people and sources. There’s a traditional idea of influence, which is about getting crushed under the weight of the canon in some way. But you’re talking about it as a playground. You can try on your antecedents, you can develop and change, not quite through impersonation but through engagement.

GBA lot of pictures by amazing artists get somewhat lost if the debate is about originality, but as soon as you abandon the idea of originality, accept it as a complete impossibility, which I think Deleuze and Guattari felt we could, then everything is far more playful and flexible. It becomes a celebration.

HKI find that there’s pleasure in your work, in addition to anxiety. It’s not a straightforward nostalgia for the human that’s being lost; there’s something ecstatic and filled with potential.

GBI remember some time ago somebody saying to me, “I just can’t look at your work, my eyes slide off it. I just can’t concentrate. I don’t know what the surface is, it’s too flat, I can’t see the brushstrokes. I don’t know what’s real and what’s unreal. Your paintings are very irritating and I can’t look at them.” This was a criticism. I wasn’t sure how to take it because I didn’t disagree, I couldn’t disagree.

HKIt depends on one’s orientation toward that experience.

GBI came to the conclusion that a certain amount of displeasure in looking, a certain amount of repellence, was actually what I wanted. Why? If you look at fiction and filmmaking, there’s plenty that makes you not want to look, plenty that makes you not want to read, makes you want to put the book down. But then you pick the book back up again because you want to read the next bit. I like to be taunted with the idea, “I can’t go on. Oh, I will go on. I can’t go on. I will go on.” We are all waiting for Godot.

HKThere’s a restlessness—yes, that’s a word I’d apply to your work. Traditional sorts of visual comfort involve being able to rest your gaze placidly on an object and feel “Yes, this affirms me.” That seems to be just what you’re denying. There’s a continual complexity, where things are ramifying and branching off—

There is a point in painting when a work gets a certain attitude, one that is slightly separate from mine—that’s when it comes alive.

Glenn Brown

GBSlippage.

HK—and slipping. That’s exciting to me, and pleasurable, if in a scary, sometimes mildly nauseating way. Am I looking at flesh decomposing? Am I looking at somebody’s eye changing places? But that’s exciting, because I want to see what’s next.

GBI want my paintings to be between states in every way you can think of, between beautiful and ugly, between violent and passive, between happy and sad, between male and female. A lot of the figures in the paintings are sort of androgynous: one person sees a boy whereas another, a girl. That occurs quite a lot—gender slippage. Apart from the old men with beards, you can definitely tell those [laughter].

HKI wanted to talk about your brushstrokes: they’re neat, meticulous even, but there’s a sort of simulation of messiness. And you have a neat studio—a lot of painters may be less tidy. You seem like you’re quite a neat person, so are you simulating messiness and decay? What’s your relationship to them?

GBI wouldn’t say that was messiness, I’d say it was complexity. I’m not trying to replicate mess—well, maybe I am to some extent. Maybe I’m jealous of the way other artists can be freely messy on their canvases, and have these accidental drips and smears that appear so perfect. I have a fear of the accidental but you have to make mistakes. All experiments go wrong at some times. I just tend to hide my wrong moves with further complexity.

HKI think it’s a universal truth that writers are jealous of painters: you get to work with material and you have lots of different things you can pull out and make a mess with. For a writer it’s all just typing [laughs].

GBIt must be very difficult for writers to make a dreadful piece of writing into a perfect composition, isn’t it?

HKI’ve fooled around with chance, playing with spell-checks and Microsoft Word grammar checks to try to find ways to introduce accident. I’ve found translation software is quite useful. I’ve got some fun pieces that I’ve made by passing a piece of text through a translation software again and again and again and again. I once wrote a text on Gavin Turk that I did that to, and Gavin kind of gamely put it in a book [laughs]. White Cube ended up as White Bucket [laughter].

GBAww. That’s quite sweet. How often was it passed through the software?

HKI don’t know, probably seven or eight times. What usually ends up happening is that you get growths, outcroppings of repetition that arise because something has been corrected again and again. Meanwhile, we haven’t spoken at all about the objects that you’re making. When did you start making sculpture?

GBThe first sculpture I made in paint was in the mid-’90s. I was making the paintings based on Auerbach. His paintings are about sitting on the picture plane and my paintings sit in another world, on the far side of the picture plane. I always see the flatness of the picture as a window through which you look to see another world. The first sculptures I made were heads based on particular Auerbach paintings, and I wanted them to appear as if they’d popped out of the painting and onto the floor in front of them. But sitting them on the floor in this abject way was a little too much: people used to kick them and they’d roll across the floor. So I started putting them on tables—

HKThey’ve got plinths and tables.

GB—and then I had to put Perspex on them because people wanted to touch them and break bits off. Oil paint is delicious, tactile, and smells so interesting, and the color is so malleable and fluid. In this exhibition I’m not covering the sculptures. We will have to trust the viewers not to be so tempted, but there will be guards, of course. I want to give people the full, sensual, abject quality of lots of fresh oil paint.

HKThere’s something pleasing about these simple modernist forms. Why do you think of them as abject?

GBPerhaps it’s my lack of control.

HKRight, but not in themselves. What I’m getting at is Georges Bataille’s idea of the informe: you have a lovely classical bronze and you put gloop over it. Once upon a time that would have been a modernist shock.

GBThey’re meant to have no set structure. They’re stuck halfway between a tree trunk and a human head or human figure. Whether that makes them abject or not is a different matter. They’re neither paintings nor sculptures—they’re three-dimensional paintings, really. Again it’s about opposites, the hard bronze and the soft paint, painting and sculpture, classicism and Baroque, the classical ideal of the human figure and then this grotesque idea of the human figure.

HKAre you interested in scholar’s rocks?

GBYes, the idea that you can have a found object that’s every bit as beautiful as modernist sculpture but it has no author. That’s the problem that society has with them, that they’re not authored and therefore we can’t read them in the way we read art or literature.

HKThat’s the Duchampian thing, framing them or placing them in a context that says, “Look at this.” That’s then the artistic gesture.

GBWhich works to a certain degree, but with scholar’s rocks I think it’s different. Because no matter what frame you put on that scholar’s rock, the good ones are so beautiful to look at that you can’t do that Duchampian framing: it’s not an object that was made to shovel snow or hang a bottle on or move a bicycle. With Duchamp, you’re looking at something man-made that was not meant to be art but was clearly designed by someone. With a scholar’s rock you can’t get that frisson, because it wasn’t meant to be a thing—it wasn’t made by humans.

HKYes.

GBAs far as I know, Henry Moore, although he came close, never took a found piece of stone and said, “Here you are, here’s a sculpture.” That was a step too far for him. And Duchamp never took a nonhuman-made object either. Even a cuttlefish bone has to be wedged in a birdcage with marble sugar cubes, so it becomes a material part of a work rather than a work in itself. We can always read them as being authored by somebody. Even the bicycle wheel has an author.

HKI was reading about one of the techniques of contemplation that Chinese scholars would do with the rocks. It had to do with scale: they’d look at the surface of the rock and try and grow it in their minds to a size where one could pass through the landscape as a traveler.

GBIt’s interesting that the value of scholar’s rocks isn’t based on size but rather on beauty. Scale doesn’t factor into their value.

HKYes, and somehow changing the scale is part of the discipline and part of the spiritual practice.

GBIn my own work, I had been making all these artificial brushmarks and I wanted to do some real ones. When I make a painting and when I make a sculpture, there’s very little difference in my head—I feel the same decision-making process going on. When I initiate a painting, I make a colorless copy on the surface, just to make sure everything is in the right place and everything has the form I want. Then I start adding color over the top of this grisaille. The sculptures start in a similar manner. The first stage is monochrome as I build up layers of acrylic paint in thick brushstrokes, layer upon layer of brushstrokes, but no color yet. Then I thickly apply the oil paint, using the same brushes but very much considering color and composition. I make sculptures in the same way I make a painting. I definitely see them as three-dimensional paintings.

HKDo you work with assistants?

GBNo.

HKNot even to stretch canvases or anything like that?

GBI don’t use canvas, so [laughs] . . . the panels are made by somebody else, though.

HKYou never use canvas? It’s always board?

GBWell, earlier paintings are on canvas, but canvas or linen can crack so I’ve steered away from that. I want a very flat, smooth surface. Nearly like a photograph, just with a hint of texture, a nod to the history of painting.

HKDo you use a particular kind of board?

GBMostly aluminum. Which I don’t like that much because it’s cold, it’s like painting on the side of a Land Rover [laughter]. It’s not human. Some of them are on wood and that’s much nicer. It’s warm. It’s human.

HKYou’ll have to get a little painting warmer [laughter].

Artwork © Glenn Brown