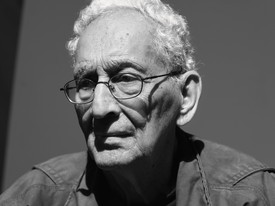

We invited Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, director of the Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Turin, to select two outstanding arts professionals to join her in a conversation about their career trajectories, current projects, and goals for the future. She chose Sarah Cosulich, the artistic director of La Quadriennale di Roma, and curator of mut, Mutina for Art, Modena, and Elvira Dyangani Ose, director of the Showroom, London, and member of the Thought Council at the Fondazione Prada, Milan.

Carolyn Christov-BakargievElvira, do you remember when we met?

Elvira Dyangani OseI was at Cornell for my PhD, and when you were preparing Documenta 13, Salah Hassan invited you to come to our student symposium to speak about the preparations for the project.

CCBYes, it must have been 2010. Hassan was on my advisory committee for Documenta, so when he invited me to give a seminar, of course I did. You and I have run into one another many times since then. I’d love to hear about the course that led to your current position at the Showroom, in addition to all of your other projects—it’s intriguing the variety of paths that we’ve all taken.

EDOWell, I never intended to be a curator. In the early 1990s I moved to Barcelona to study at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona; I wanted to become a writer. I thought I’d study journalism, but in my first year there I met Teresa Camps Miró, who taught in the art department, and I discovered that I could write in that context too, and that art history gave me a subject to write about. Through that program I met a group of students who were working with Teresa on a platform to engage with living artists from Barcelona and bring their art to the campus. I cocurated my first show there, Terra, in 1994.

This directly provoked my interest in interventions in public space. I remained in Barcelona until 2004, and was part of a curatorial collective that used shop windows and community centers as display spaces for artists who didn’t have the opportunity to show in the city’s bigger institutions. Those concerns and interests continue to inform my work.

CCBYou mentioned your professor—were there other mentors, or other experiences in Barcelona, that shaped your thinking?

EDOThe philosopher Pep Subirós curated an exhibition at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona called Africas: The Artist and the City [2001], where he invited dozens of artists to participate in the show and a symposium. That had a profound effect on me: suddenly I was able to encounter all these artists who were questioning or struggling with issues of identity, postcolonial subjectivity, and the meaning of art in the African context. That exhibition, and my experience around it, were generative.

Around the same time, I also had the chance to meet and work with Coco Fusco on the production of her video Els Segadors [The reapers]. She was critical for me.

CCBShe was very important for me too. She has come to Castello di Rivoli to lecture. I think her ideas around border zones and her performances with Guillermo Gómez-Peña are wonderful.

EDOAbsolutely. I left Barcelona when Alicia Chillida invited me to be part of CAAM [Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, Las Palmas], in 2004. We worked to rethink what it could mean to produce culture from the perspective of a community that was a geographical enclave between Europe, Africa, and America, and to consider that as an intellectual arena in which to develop a project. I then moved to Seville, where I worked at CAAC [Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo] for a time, before moving to the United States. After my PhD program at Cornell, I went to London to work at Tate Modern; that was in 2011. And now I’m at the Showroom and on the Thought Council for the Fondazione Prada.

CCB Before we discuss these projects in more depth, Sarah, could you tell us about your trajectory? I’ve been fascinated by the work you did as a young woman, working closely with Francesco Bonami on the fiftieth Venice Biennale, and then in five years of curating not far from Venice at the Villa Manin Centre for Contemporary Art, and then later when you were directing the Artissima art fair in Turin. Now you’ve been appointed the artistic director of the Rome Quadriennale, an important event in Italy. I’d like to know a little about your education and your early work. You’ve straddled the commercial sector, in running Artissima, and more curatorial, art-historical activities—how did those coalesce in your career?

Running any institution means thinking about the context, mission, and audience to which that project is targeted and thinking about what you can bring in terms of added value.

Sarah Cosulich

SCWhen I was doing my master’s in London at the Sotheby’s Institute of Art, in 2000, there was a strict division between those who were planning to go into the commercial sector and those who were planning to work as curators. It was reflected even in the way we were seated. I assumed that was normal, and that it was the rule to decide at that early moment where you wanted to work in the art world. I always wanted to be a curator, which is what I went on doing, but in 2012, when I was chosen as Francesco Manacorda’s successor to direct Artissima, I had to learn to lead an art fair as a curator. It was a task full of challenges—the lack of close contact with artists being the most difficult one—but also full of opportunities to develop strategy and vision. I learned to recognize the talent of others—not just of artists, as when you curate, but of everyone who can make a program stronger and therefore successful.

CCBWhat do you think you contributed to Artissima that changed it?

SCRunning any institution means thinking about the context, mission, and audience to which that project is targeted and thinking about what you can bring in terms of added value. So for Artissima I analyzed the situation of Turin. Rather than copying other international models, I wanted to be international by starting from Turin and what its network had to offer: incredible institutions, museums, collections, and much else. These were catalysts for the development of the fair’s identity.

CCBBefore that you worked closely with Bonami. What did you take away from that experience?

SC I’d studied and worked in Washington, DC, Berlin, and London, where I had just completed my master’s. I’d spent time at Tate Modern and had curated an exhibition of Pawel Althamer’s work in Trieste. I landed at the Biennale with Francesco by sending him my master’s thesis, which was on Maurizio Cattelan and the tradition of commedia dell’arte in Italian theater, literature, and film. I had the most exhilarating interview with Francesco—basically a walk through Venice—and one month later I was working closely with more than fifty artists such as Fischli and Weiss, Matthew Barney, and Thomas Bayrle (whom you, Carolyn, showed so importantly at Documenta), and with curators such as Hans Ulrich Obrist, Carlos Basualdo, and Daniel Birnbaum. That experience definitely gifted me with one of the greatest learning possibilities ever, in all directions.

CCBAnd with responsibilities, too.

SCDefinitely. Francesco has an incredible ability to delegate and trust the people he works with, while at the same time transferring a precise vision and sensibility. He can be a mentor by telling you a joke or a funny story and yet you know that few people care about art more than he does. Francesco connects incredibly with artists, respects the audience, and is generous to younger curators working with him. I’m just one of the many with international careers who started as his collaborators.

EDOCarolyn, your own career is extraordinary—would you give a quick recap before we discuss what we’re up to currently?

CCBMy beginnings in art go back to the 1980s. The first exhibition that was important to me, Non in codice [Not in code], I did with Mario Pieroni’s gallery in 1987, in the gardens of the American Academy in Rome. Dan Graham and I picked all the artists. Thanks to his involvement I got to meet all these wonderful people, including feminist artists like Barbara Ess, Dara Birnbaum, and Judith Barry, and also Rodney Graham and John Knight. It was also my first catalogue! Sol LeWitt designed the cover. I had no idea how to design a cover, so Mario said, “Why don’t you go to Sol’s house in Umbria, he might help you.” And he did, he designed the cover, which was this beautiful gatefold.

Shortly after that, working with a friend I curated Molteplici Culture [Multiple cultures], which was held in a museum of folklore in Rome. Here there were artists like a young man called Damien Hirst—his first international outing—as well as David Hammons and so many others. It was a true insiders’ escapade, with only seven hundred visitors. Through that show I met one of my main mentors, Alanna Heiss. From 1999 to 2001 she would be my boss at PS1, the space she founded in Queens, New York. Then in 2001 I joined Ida Gianelli at Castello di Rivoli. Feminist thinkers and artists were important to me: the theorist Griselda Pollock and artists like Etel Adnan, Anna Boghiguian, Bracha Ettinger, Carolee Schneemann, and Lubaina Himid. And I had other mentors in terms of my thinking, such as Donna Haraway and Judith Butler—meeting these women changed my trajectory. The real mentors were not in university.

I ended up running the 2008 Sydney Biennial, which was on the subject of revolution as a form and also as a political engagement. “What does it mean to revolt?” was a key question. After that, from 2009 to 2012, came Documenta, a big four-year project that took me to many parts of the world. Working in art, we’re not like businessmen, who when they travel stay in big hotels at the airport and meet only very wealthy people—we end up in neighborhoods with local people who are very welcoming, so we end up knowing more than we would if traveling for business. This happens through alternative art spaces everywhere: from visiting Tang Da Wu in Singapore, who started the Artists Village in 1988, to hanging out with artists in Hanoi. It was an intellectual search for meaning, and that turned into Documenta 13.

My biggest challenge at the time of Documenta was to prove that a singular curatorial vision could make an international exhibition that was relevant. At the time, nobody thought biennials were interesting anymore, they felt the art world’s attention had moved away from them toward on the one hand the auction houses and on the other hand the art fairs. In my view, the art fairs were connected with the emerging form of the digital. In the same way that we open files and folders on our laptops, in an art fair you can get very quick fixes, you can spend one day and get absolutely up to date on what’s going on, and you can see several projects concentrated in one place. Each gallery booth has no need for a relationship with the gallery booth next to it, because seeing them is like opening and closing digital folders.

I’m thinking of the museum as a time capsule that can transport poetic aggregations into the future, and therefore not become obsolete.

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev

So I felt that the international exhibition that came out of the vision of one person, with a team, needed to make a resurgence. This was something I’d learned from Harald Szeemann, who taught me about the importance of the exhibition, the Kunstausstellung, that’s like a construction, or a novel. It’s made of artworks, some new, some not, but it has a value in itself as a semiotic object. Also from Achille Bonito Oliva, an Italian curator to whom we’ll be dedicating an exhibition in 2021, for his eightieth birthday, comes the narcissism: if I have an idea about the world and what’s going on in the world, I’m sure it’s right [laughs], I just have to apply it. Of course we need to keep such feelings in check! But what I was trying to do with Documenta, and I think I achieved, was to shift this idea, to say, “No, it’s not true that the international exhibition made by a singular curatorial voice is obsolete. It still has relevance.”

After Documenta I mostly went into teaching. I was feeling a little burned out, and didn’t want to work on exhibitions or with artists. I went into a kind of—not depression, but feeling like I should think about all these things and dedicate myself more to giving it all back by teaching younger people. So I taught at the Goethe-Universität in Frankfurt and I did seminars and taught at Leeds University with Griselda. I went to study at the Getty Research Institute as a scholar, and then taught at Northwestern University for some years. Also, in 2013, I conducted a seminar at Harvard that was very important for me: it was about how to reinvent museums in the future, taking the interdisciplinary outlook of the Documenta and seeing how it might be applied to the organization of museums.

Now, similarly to what I did in Documenta as a temporary museum, I’m doing with the Castello di Rivoli in terms of what the museum is or can be. In May 2019, for example, we incorporated the Cerruti Collection. That has to do with collecting the collector: it’s still a museum of contemporary art, but why did he buy that Jacopo del Sellaio Madonna and Child, in that year, in that moment, and put it next to a contemporary work by Giulio Paolini? So we can traverse different historical periods and resolve our problem of going beyond the notion of “contemporary art,” which I find obsolete, because everything that exists is contemporary—whether it’s my old shoe or my new cell phone, it’s all in the field of my perception, and therefore it’s contemporary by nature. I’m thinking of the museum as a time capsule that can transport poetic aggregations into the future, and therefore not become obsolete.

SCDo you think this is a direction other museums too should take?

CCBOf course, it’s the only way to survive. The thing that public museums have that nobody else has is eternity. The normal cycle of collections is that they eventually get broken up and sold. The provenance of an artwork grows with those sales, and there’s something lovely in that, but there’s also a loss of all these visions of art that once were, so in the idea of collecting the collector we’re working on that. At the same time, we’re also working on another important matter: the rewriting of the canon.

There’s a need to create a cultural environment, and I think individuals should be encouraged to invest in that, almost as a way of giving back to the context they’re from.

Elvira Dyangani Ose

EDOToday I was asked what the fact that some of the biggest collections are owned by individuals meant to me. Controversy aside, that’s a twentieth-century question. The question should be a different one: how to sustain a healthy art ecology. There’s a need to create a cultural environment, and I think individuals should be encouraged to invest in that, almost as a way of giving back to the context they’re from—not only to generate art, or to support the intellectual labor of curating, but also to help people to envisage what it means to build an institution, what it means to meet the technical responsibilities of those institutions, what it means to conserve a legacy. And then, to me, the second part of the argument is the understanding of art in so many of these communities and cultures—it needs a proper context. The fact that something is purchased by an international collector doesn’t change the need to build institutional knowledge that can engage with understandings of art that are different from what signifies in the West.

SCIt’s true. Looking at the renegotiation of the canon, there is this question of who is more able to do that—

EDOIt’s important to define the position of privilege we’re in and to work from there. For instance, when I joined Tate Modern as the curator of international art, I decided that I couldn’t think about a strategy to enhance the collection’s holdings of art from Africa and its diaspora without bringing all the protagonists, experts, and agents of that field to the Tate in one way or another.

CCBSpeaking of bringing people in from far and wide, Sarah, can you tell us what the Quadriennale is and what your goals are for it?

SCWhen the Quadriennale was founded, in 1927, it focused on Italian art, while the Venice Biennale was more dedicated to international art and the Milan Triennale to design. That was the vision for the positioning of these three projects. I want to rethink the role of the Quadriennale in this new global landscape, creating ties beyond the country’s borders and opportunities for Italian artists to engage in dialogue and exchange. Internationally there’s a vast amount of knowledge and awareness of historic Italian art, but contemporary Italian artists, younger and mid-career, don’t have that many opportunities to exhibit in institutions worldwide. I want to understand why, and to envision strategies and initiatives that could extend the Quadriennale beyond Italy.

CCBHow are you working to achieve that?

SCThe Quadriennale is first of all an exhibition. The 2020 edition, titled fuori (Out) and curated by me and Stefano Collicelli Cagol, is scheduled to open on October 29, featuring forty-three artists in the 4,000-square-meter space of the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome. It will focus on Italian art of the ’60s but will give a lot of space to younger artists as well. The show will offer an alternative narrative of Italian art outside the classifications that for a long time dictated the canon, like those between disciplines or gender.

The Quadriennale d’arte 2020 is the main and final part of my three-year program with the institution, but not the only one. We have also developed Q-International, a grant aimed at helping institutions abroad to show Italian artists, and Q-Rated, a series of workshops around Italy that puts fifteen artists and curators aged under thirty-five—different in each place, and selected through a public call—in dialogue with relevant art-world figures, from museum curators to established artists. You hosted us at the Castello di Rivoli, Carolyn, and it was great; the other workshops took place in Naples, Sardinia, Turin, Milan, and Lecce. They not only offered opportunities for discussion of different themes but gave Stefano and me the chance to do research for the Quadriennale exhibition.

After covid we’re going to have to do a lot of rethinking of how much we were traveling—of how practices need to be rooted while at the same time staying open.

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev

CCBThat’s great. And in a way your work is now more local than it was before, because you’ve taken on this institution that traditionally deals with artists from Italy; this is timely during covid, when travel has become extremely difficult. After covid we’re going to have to do a lot of rethinking of how much we were traveling—of how practices need to be rooted while at the same time staying open.

Elvira, what you’re doing at the Showroom and Fondazione Prada ties into this key concept of exchange. Could you say a bit about what you’re doing there?

EDOThe Showroom is a small organization that began in 1983 as an artists-led pop-up exhibition in London’s Covent Garden. My predecessors transformed it, positioning it as a collaborative institution providing a critical stance on core issues in the field. Working with Louise Shelley, Emily Pethick created the Communal Knowledge project, which aims to develop artworks and discourses in relation to our neighboring communities. As a way to build knowledge through collaborative practices, experimentation, and transdisciplinarity, that project now informs the organization’s program as a whole.

CCBSo the Showroom’s activities take place throughout the communities you’re engaging?

EDOWe work with communities and agents of those communities, operating both hyperlocally and worldwide. That may mean working in a library or a hospital corridor; it may mean working with people in São Paulo or Madrid.

CCBAnd what are you doing now? Or are you in a bit of a pause due to the pandemic?

EDOWe’ve been on hiatus for a while. But next year we have exhibitions with the Arab artists Haig Aivazian and Inas Halabi, part of a collaboration with the Brussels consortium Mophradat. Then I have other projects in the pipeline as an independent curator. One is a sort of artists-led festival, HacerNoche (Crossing night), which will happen next year in Oaxaca.

CCBYou both had incredible mentors. How do you approach younger arts professionals and curators—what does it mean to mentor somebody else? How do you approach mentorship within and beyond your institutions?

EDOWell, you don’t approach a mentee, they come to you, no? [Laughter] There’s much I would say. I remember that when I was a student, and deciding that I wanted to work around modern and contemporary African art, I was living between Barcelona and Las Palmas, so I was determined to email everybody I was interested in as my sources of knowledge. I wrote to so many people—academics, curators—some of them responded and some are now good friends. I also traveled to Paris, Bordeaux, Brussels, and London, hoping I could meet them, hoping they’d be in their office and I’d just knock on the door and find them. Then at some point in your career, you realize all of a sudden that people are asking, “Can I come work with you?” They’re not your students, they’re people in the field who want to sit down with you. I don’t think I’m a mentor in that respect, I don’t see myself as that, but perhaps people perceive me as such and I welcome that perception. What I’m trying to do is have a lot of dialogues, to offer platforms where it’s possible to indicate possibilities, but also to encourage others to believe in what they want to do, because that’s the only way forward. Ask unapologetically for what you want. Proclaim your wishes. And then start walking toward that space. When I see young artists and curators, I tell them, “If you don’t find what you want in the space where you are, invent it. Find alliances with others who perhaps feel the same way.” Disenfranchisement can be the catalyst for so many other possibilities.

SCI feel the same. “What advice would you give?” is really a difficult question. We’re not working in a field that gives you many opportunities, so it’s about balancing a realistic attitude with an inspiring message. It’s such a privilege to be active in this field. And Elvira, what you said about choosing I think is very important: the idea that you continue to dream and do many things, but there’s a moment where you have to choose, because the choice is what gives you credibility and a position. How about you, Carolyn? Any advice?

CCBI don’t think there’s an objective, absolute advice that always works. As you both know, I think it’s very important to be close to artists—that’s not a given, but it’s one of the forms of power that curators have. On that topic, the important rule is to be honest, to lay it straight. Good artists hate beating around the bush, and hypocrites, and people who want to get something out of them.

The other thing I’d advise has to do with writing. I think the Internet has brought a collapse of intellectuality. A lot more information is available, and a lot of data to process, but the minute you try to scratch a little bit, there’s almost nothing on the Web if you truly want to learn about anybody’s work. It’s important to read outside the Web, and to write—and not only to write one’s personal opinion but to contribute scholarship to scholarly publications. Working deeply and slowly on individual artists is important to me.

Another thing I’d say is, don’t be scared to break beyond the boundaries of the fine arts. The field of art, the way we discuss it, whether at Gagosian or the Quadriennale or the Castello di Rivoli, is based on eighteenth-century Enlightenment concepts. In the Europe of the Middle Ages there was no idea of art as this autonomous practice of aesthetic research that is somehow a form of embodied philosophy. That’s a very eighteenth-century, [Johann Joachim] Winkelmann–like concept, which first became universal in the West and then was imported to the rest of the world. Today the canon and the concept are breaking down. We now believe that the boundaries around the so-called fine arts—between the fine arts and activism, say, or urban-development studies, or science and research—are ending. I’m proud to have put quantum physicists in Documenta, and the geneticist Alexander Tarakhovsky. In a few years, probably, there will be new fields of knowledge and knowledge production, and new boundaries around what those fields are. But in the meantime, here we are, alive, and I say this paradoxical thing, which is that although art may not always exist, artists will, and what artists do will continue to be done.

Also, individuals aren’t popular right now—instead we have these fake individuals, like certain politicians, who are complete constructions. We’re in an era where the collective subject is dominant. Nothing comes out of this incredible Internet that isn’t the fruit of a sort of collective subject. Even when it aggregates around certain opinion leaders, they’re ultimately vacuous figures of spectacle onto whom all these collective feelings are projected. No scientific papers are published today with just one author, it’s always a collective, because there’s just too much data. But I don’t personally see the collective nature of knowledge right now as a challenge toward which I need to move; it’s just the status quo in an advanced digital era of social media and of an attention economy. What’s more a challenge for me is to see what procedures of individuation occur, or can occur. So my advice would be to go a little against the grain of what the tendencies are right now—not for the purpose of pure originality, but just because the work of an individual person would otherwise be lost in this wave of big data. It’s so important to collect the pieces and the poems and the letters and the artworks and the paintings of just one little person in one little corner.