Ninotchka Bennahum is a dance scholar and curator. She is a professor of theater and dance at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and the author of Antonia Mercé, “La Argentina”: Flamenco and the Spanish Avant-Garde and Carmen, a Gypsy Geography.

Mark Franko is Laura H. Carnell Professor of Dance and heads the Institute of Dance Scholarship at Temple University. Dancing Modernism/Performing Politics was reissued last year in a revised edition from Indiana University Press. Text as Dance: Walter Benjamin, Louis Marin and Choreographies of the Baroque is forthcoming from Bloomsbury.

Gillian Jakab is an editor, online and print, of Gagosian Quarterly and has served as the dance editor of the Brooklyn Rail since 2016.

Mark FrankoCould you say a little about how you got the idea for Border Crossings?

Ninotchka BennahumThe title changed over time. The exhibition offers histories of modern dance seen through the lens of the exiled, marginalized, and refugee artists whose border crossings are the result of geopolitical conflict—war, revolution—and structural racism. Exile, an exilic modernism, became the spine of the exhibition thanks to my research on another project. For many years I worked as the dance historian for the American Ballet Theatre. When I joined the faculty of the University of California, I began thinking seriously about a critical and historical examination of the company. Ballet Theatre, as it was known at its genesis, was founded at a bad time in history, on the eve of World War II, which coincided with virulent racism in the United States and the coming international conflagration of world war. As I pored over letters, diaries, contracts, and production notes, the relationships between neoclassicism, modernism, and the trauma of the twentieth century coalesced.

This came out of our discussions with one another, Mark. You were my last teacher at New York University’s Department of Performance Studies. I gained so much from your seminar on dance modernism, including discovering the roots of exiled and marginalized artists. These vital discussions led me to the title for my book now in manuscript, Exile and Modernity: American Ballet Theatre in the Shadow of War, and also to many aspects of this show. Also my mom, Judith Chazin-Bennahum, in her book on René Blum, focused on the traumas of the twentieth century woven into the onstage ethos of contemporary dance.1

GILLIAN JAKABWhat’s particular about dance in relationship to these themes of modernism and exile?

NBIn the exhibition, I wanted to explore the notion of modern dance as containing urgency, as having a momentum distinct from technique, distinct from the aesthetic properties that critics such as Clement Greenberg characterized as self-reflexive. Although modern dance defended its autonomy from the other arts to assert its own unique identity, this became confused with aesthetic autonomy tout court. The idea that modern art takes itself as its own subject matter became a sort of tyranny, which still governs quite a bit of how we analyze “the modern” in visual art, literature, and music. But what’s missing from that definition when you have an embodied form, like dance? Where dance is concerned, what can autonomous art and self-referential form mean?

One answer, for me, comes from the “exilic presence” within modern dance, which to my mind was triggered by the rise of fascism in Europe, the formation of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade—an American volunteer battalion that fought fascism in the Spanish Civil War—and the militarized street mob (which we’re seeing again now in the United States). These gave rise to a clear radical consciousness, in this context among the 1930s dance artists you wrote about, Mark, in your book on dance and the labor movement: Edna Ocko, Jane Dudley, Anna Sokolow, Eve Gentry, Lily Mehlman, Syvilla Fort, Si-lan Chen (a committed Marxist-Leninist).2 This group was attuned to the dangers of the world and many had relatives in Europe. From General Franco’s invasion of Spain from Morocco, triggering the Spanish Civil War, to the aerial bombings of Guernica (April 26, 1937), to Kristallnacht in Germany in 1938—all this triggered a refugee crisis, a maelstrom of geopolitics and human displacement that brought about the loss of lives. The story of danger and the refugee body, of the asylum seeker in the United States and in the world of modern art, is not new. But what is new in relation to dance modernism is that it is not just obedient to the ideology of self-reflexivity but constitutes a corporeal language of the modern in an existential sense: the lingua franca of movement in crisis, its ethos, its drive, it becomes the language of the radicalized political body. And the political body displaces the primacy of the avant-garde, because its radicalism is no longer limited to the strictly aesthetic or formally innovative.

Then there are the artists exiled within the United States, in a sense: the Black, brown, and Indigenous people. There are multiple vectors: the physical transfer of ideas from Europe to the United States in the bodies of asylum seekers, but also the exclusive forces within the United States, beginning with the complete failure of Reconstruction in the later nineteenth century. After Nellie Cornish, founder of the Cornish School in Seattle, advocated that the Black dancer Syvilla Fort be admitted, she was asked to leave the board. Fort went on to choreograph with Merce Cunningham in 1939. In addition, she commissioned a composition for prepared piano, Bacchanale, from John Cage, who was teaching at Cornish. Bacchanale is in the exhibit. These two white men go off to great fame, but very few people have heard of Syvilla Fort. In fact, we have not a single record of her dancing and only a rare and wonderful film of her teaching in the Phillips-Fort studio. These are the archival gaps we attempted to resolve.

MFYou’re doing something very interesting in this exhibition. I love the phrase you use, “internal exile.” We move from the geopolitical forces that send people moving across the globe to the individual dancer, their career trajectory, their struggles in their milieu—it’s very biographical. Could you say a little more about that—how you came to the realization that by pulling those two threads, the global and the individual, they would merge?

NBI was thinking about the scholar Saidiya Hartman’s phrase “if inequality structures the world.” The question was, could we show the marginalized and underrepresented artists of modern dance as exiled from its history, while also foregrounding the history of modern dance as itself founded on exile? An artist like Pearl Primus, for example, brought the vocabulary of modern dance together with US southern labor songs and Afro-diasporic dances and mobilized them toward social justice, toward the New Dance Group’s political manifesto “Dance as a weapon for social change.”

GJYou mentioned that the exhibition came to be through many conversations with Mark. There’s also a catalogue in the works with contributions from twenty different dance historians. Could you speak a little about how you engaged with the work of other scholars for the project?

NBWell, Mark trained me, fellow dance scholar André Lepecki, and many others, and he’s maintained an ongoing conversation with his students since then. It’s a lineage. The field has blossomed in the last few decades—very exciting. It was a gift to have that mentorship, pedagogy, and insight.

In addition, we thought the show should have a book as both representative of the exhibition and an extension of it. It’s an opportunity to bring in other scholarly perspectives and to enable graduate student research. We wanted to identify certain artists who are not written about enough, like Si-lan Chen. If we put forth more comprehensive intellectual information, perhaps someone will write a biography. The exhibition catalogue was curated carefully to represent the exhibition on both coasts, to represent different stages of scholarly engagement, interdisciplinarity, and also to bring in the most central parts: colorism, racism, radical pedagogy, border crossings, the trauma of two world wars, the Spanish Civil War, revolutions, et cetera, as a methodology for understanding the language of asylum as it becomes corporealized.

MFYou completely avoided New York–centrism. I was very impressed.

In the exhibition, we meet the California-born dancer Yuriko Kikuchi, who was forced with her family into an internment camp during World War II because her parents were of Japanese ancestry. We see her through photographs from Martha Graham’s work. One is a beautiful image of her in Canticle for Innocent Comedians in 1952. There’s a double layering—the movement of exile opens into individual biographies as well as shared movement philosophies. Graham choreographed by working with Yuriko’s body, a body that contained a history. If I could imagine seeing Canticle today with Yuriko, I wouldn’t be thinking directly about her personal vision of choreography, necessarily, or what she’s bringing to this as a Japanese American, but it would still come through the work of someone else.

To me that’s part of what you’re saying here: that a dancer can embody and transform roles and spaces. While there were certainly racist barriers in modern dance at the time, as a young observer of dance in the 1950s I felt the power of diverse perspectives. Dance scholarship hasn’t encompassed this range of identity; we don’t see the full history. We have many brilliant monographs on different artists, different companies, like Alvin Ailey, so that’s filling in gaps, yet despite progress over the last twenty years, it’s still compartmentalized. This exhibition is the first time I’ve seen the expansive vision that I had immediately when I saw modern dance as a child.

NBThank you. That was the goal and you are the first person to articulate it.

The historical context is striking to me as a way of seeing Yuriko’s relationship with Graham. She comes to Graham, released from internment, and says, “I am Yuriko. I have just spent eighteen months in an Arizona concentration camp. Hire me.” She makes it clear that having been interned, having been arrested, having been rendered stateless like everyone on a Nansen passport—a passport document issued by the League of Nations in the interwar years to help refugees who had lost their national identity—forms the perspective from which she will perform Canticle. The egregious nature of these internal physical borders—the racial cartography of the internment—and the carving up of the nation into citizens and “noncitizens” suddenly stripped people of their legal status under Executive Order 9066. Yuriko, Graham’s first nonwhite dancer, danced Canticle, as did the great African American dancer Mary Hinkson, who joined the Graham company after Yuriko in 1951.

By the 1960s you witness a jazz-inspired freedom in the body, an improvisational élan, in that wonderful art film On the Sound (1962), with Hinkson, Matt Turney, and Donald McKayle—that’s the transition. Brown v. Board of Education is in 1954, and this echoes Beat culture and foreshadows the arrival of hippie counterculture, and the conversation changes. The exhibition ends there.

GJYes, I was curious about the decision to end the exhibition in 1955.

NBWell, in addition to this political shift, it specifically stopped in 1955 with Anna Halprin and the California beginnings of postmodernism in dance. That was the creation by Lawrence Halprin of Halprin’s dance deck and the construction of the San Francisco Dancers Workshop among the madrone trees of Marin County.

MFModern dance may have ended in 1955?

NBHalprin said it had to end. She said, “This is a postwar moment. I’m done.” We understood that Anna broke with Martha Graham to make room for postmodernism; modern dance had to end. Still, we have to acknowledge that of course it didn’t end, because it was the medium through which the border crossing had occurred. Major BIPOC choreographers emerged. There was a multiracial and multigenerational presence in dance from the civil rights era through the ’80s: Anna Sokolow, Donald McKayle, Eleo Pomare, Paul Sanasardo, Pina Bausch, Bill T. Jones, et cetera. Carmen de Lavallade—who danced with Carmelita Maracci, Lester Horton, Alvin Ailey, and Geoffrey Holder—is still alive and I wanted to include more of her story; she didn’t get the kind of historical credit I think she deserves. She has an artistic vision that circulates and permeates New York City. So many women, women of color particularly, are not credited with creative innovation as national momentum. De Lavallade and Hinkson became important curators of modern dance in the 1950s and ’60s.

GJYou’re even crossing the borders of time periods in this show! There are geographic borders, the social borders of race segregation, and borders of artistic genre and academic discipline.

MFThe borders of aesthetics versus history—

NBIn terms of geopolitical borders, modern dance can be seen as an exchange between Europe and the United States, with its roots in Mary Wigman’s German expressionist dance of the 1920s. With the rise of fascism in this time, dancers often found themselves on either side of a divide. The American dance educator Margaret H’Doubler, for example, sent her modern-dance students at the University of Wisconsin to Wigman’s school in the early 1930s and went to Dresden to see Wigman in 1937. It is unfortunately a fact that H’Doubler’s students appeared in Wigman’s and Rudolf Laban’s choreographies for the Berlin games in 1936. The moral dilemma that emerges from this research is endlessly complex.

MFThey used this in the Nazi Olympic Games?

NBExactly.

MFSo that’s kind of a counterpart to Graham refusing Joseph Goebbels’s invitation to appear there.

NBRight, that signaled the tension. Graham was crystal clear on her antifascist stance. But Wigman Aryanized her school before the racial laws of 1935. In some of Wigman’s choreography one senses the rise of fascism within the body, following the coopting of modern dance by nationalist aesthetics and guidelines at these Nazi spectacles.

MFRegarding genre, choreographer Dianne McIntyre said, “What’s a border? Well, my training happens to be classical so when I deal with the racial issues that I do in my choreography, that are more common in experimental dance, I’m crossing a border.” She breaks from the restrictive conventions and expectations.

NBAnother related border you brought up is discipline—the interdisciplinarity of these artistic and political laboratories, these physical studio spaces and the dancers that modern dance choreographers were sharing. Nobody had any money. The Neighborhood Playhouse in New York became a very important intellectual hub for immigrant children and dancers in the first half of the twentieth century. There were crossovers between theater and dance, with figures like the dancer and actor Benjamin Zemach, who was close with Graham. And when Graham dancer Jane Dudley retired from the stage, the audience, her students, witnessed a political acumen, an ability to articulate definitions of dance modernism and what concerned the modern dance artist.3 For this reason she can be linked to Hannah Arendt and Walter Benjamin. Modernity is a state of anxiety, a state of existential angst. The language of modernism and exile is so clear in German literature, in Thomas Mann, for example. Why don’t we embed philosophical ideas of the body in dance and its scholarship as much?

MFThat’s what this exhibition transmits in many different ways.

GJIn terms of transmission, Crossing Borders ends with a video of contemporary dance artists, in a sense connecting what has been inherited from history with the future.

NBYes, at the end we highlight important next-gen, post-1955 artists, like Tina Ramírez, the founder of Ballet Hispánico, which today is vital to the city of New York. One of the things we wanted to do on New York soil was pay homage to artists whose dancers are going to walk through the exhibition, to honor them and invite contemporary artists to live in, to inhabit, this critical inquiry. Kyle Abraham plays a central role in contemporary dance in discussing structural racism and communities under siege. I’ve also spoken with choreographer Ralph Lemon about the whiteness of postmodernism: how is it that, if the legacy of modernism is rich and diverse, postmodernism turns its back on multiraciality? It becomes even more egregious and striking in the latter half of the twentieth century. Not that there weren’t pitfalls to modernism’s impulse toward multiculturalism; we have a section in the exhibition titled “Trespassing and Cultural Appropriation,” critiquing white artists’ vision of exoticism in the 1920s. There we display a 1930 quote by Martha Graham critiquing her teachers Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn [collectively referred to as Denishawn]’s “weakling exoticism of a trans-planted orientalism.”

For Latiné artists in particular—dance educators Michelle Manzanales and Kiri Avelar articulate this in the exhibition—the US/Mexico border is real. Avelar comes from borderlands, from El Paso, where the border wall is a painful and continuous space.

MFIt makes me think of Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilization (1961), the idea that confinement can either be within or without. And Jacques Derrida worked with the notion of the crypt of the outside within the inside, working around otherness.

NBYou’re lugging it behind you or around you or inside your body your entire life. Si-lan Chen, whose father was Chinese and whose mother was Trinidadian/French Creole of African descent, didn’t experience the racism of Jim Crow until she came to the United States and had to deal with immigration. So one’s encounter with the border as a periphery separating madness from reason comes in different moments, in different ways, at different times. There’s no single border, no single imprisonment; they’re all individuated. The choreographer Antony Tudor represented this beautifully in 1942 in Pillar of Fire. There’s a psychic wall between the character Hagar’s repression and the man in the “House Opposite.” The physical geography of the stage is separated into many mental spaces and psychic breaks. It’s a panopticon of madness and suffering and love.

GJIn a somewhat similar sense, I was curious about the physical space of the exhibition—we have to move our bodies through it and have some agency over how long to stay in front of something, when to go back, and which direction to take. How were the design decisions made?

NBCaitlin Whittington, the library’s wonderful exhibition designer, asked former Guggenheim designer Christine Rung to join their team and Christine was just incredible. We met every Friday for two years with our design team. They did a beautiful job. We made slides with proposals like “This film here,” “These photographs hung this way.” It was a collaboration. We wanted the space as open and unmediated as possible.

GJMark and I ended up starting at different ends of the exhibition and met in the middle.

MFThat space is strange because you can enter on either side—

GJ—and take your own journey.

1Judith Chazin-Bennahum, René Blum and the Ballets Russes: In Search of a Lost Life (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

2See Ellen Graff, Stepping Left: Dance and Politics in New York City, 1928–1942 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997), and Mark Franko, “Bodies of Radical Will,” in Dancing Modernism/Performing Politics (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2023).

3Jane Dudley in Dancing: The Individual and Tradition, Dance Group Films, American Dance Guild (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1993), VHS video. © 1993. See also her interviews in Mark Franko, The Work of Dance: Labor, Movement, and Identity in the 1930s (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2002).

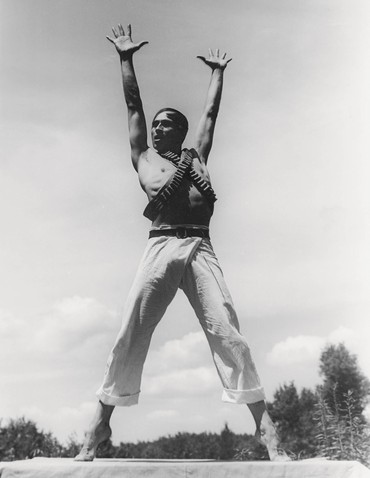

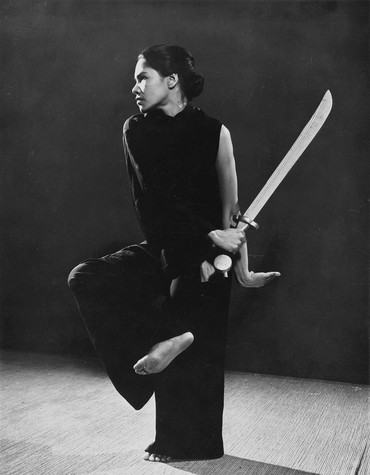

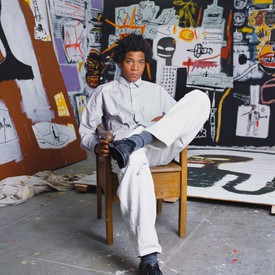

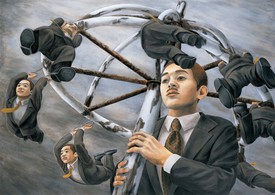

All photos: courtesy Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts