John Szwed is the author and editor of many books, including biographies of Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, Sun Ra, and Alan Lomax. He has received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation, and in 2005 was awarded a Grammy for Doctor Jazz, a book included with the album Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax.

Stanley Whitney’s vibrant abstract paintings unlock the linear structure of the grid, imbuing it with new and unexpected cadences of color, rhythm, and space. Deriving inspiration from sources as diverse as Piet Mondrian, free jazz, and American quilt-making, Whitney composes with blocks and bars that articulate a chromatic call-and-response in each canvas. Photo: Miranda Leighfield

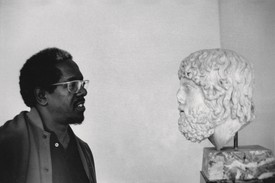

There is a hidden history of jazz and painting, one that suggests an affinity between the two arts deeper and older than we might think. In 1928, Dr. Albert Barnes, the collector who created the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, was lecturing on the parallels between Pablo Picasso’s paintings and Black religious music, one of the roots of early jazz. Jean Cocteau, Francis Picabia, Man Ray, and the composer Darius Milhaud all took up jazz drumming. In the early 1940s, pianist Thelonious Monk and Piet Mondrian met at Minton’s, the after-hours musicians’ bar in Harlem, and discussed the similarities between their different arts. There was talk of multiple perspectives in both Cubist paintings and the collective improvising of jazz bands. By the 1950s, and with the ascendency of bebop, the music that the artist Jordan Belson called “simply the most radical thing at the time” was bringing Manhattan artists and musicians together at the Five Spot or to the sound of the jukeboxes at the Cedar Tavern or Stanley’s. Jazz was referred to in the work of Franz Kline, Frank Stella, Norman Lewis, and both Willem and Elaine de Kooning, some of whom titled paintings after those musical dive bars or the names of favorite recordings. Many others, including Robert Ryman, Jackson Pollock, and Lee Krasner, were inspired by the music and used it to accompany them as they worked, as Stanley Whitney has throughout his career.

—John Szwed

John SzwedI was surprised to learn that at least sixty-five well-known jazz musicians were painters. They weren’t necessarily widely known as painters but their work was shown and sold.

Stanley WhitneyI knew that Ornette Coleman painted.

JSThe earliest I know was George Wettling, a successful drummer in the 1930s and ’40s who traded drum lessons for painting lessons with Stuart Davis, and whose paintings showed Davis’s influence. By the 1960s he was considered an old-school musician, and once, when told he should play in a more modern style, said, “I don’t need this, I’m getting more from my paintings than I’m getting from my music anyway.”

SWMaybe he thought painting could be more lucrative? Even Stuart Davis wasn’t making much money in the ’30s, but I guess they had something they could sell, whereas if you’re a musician you’ve got nothing you can sell, just gigs.

JSWhy do you think Miles Davis got into painting? He was one of the most highly paid musicians in his later years.

SWMiles did it because of [Jean-Michel] Basquiat. Because Miles was not okay with letting anyone get past him [laughter]. Miles thought he could do everything. Basquiat really wanted to be, and wanted to be around, famous people; when he went to LA, he wanted to meet all the musicians, but especially Miles. Miles went to his show, looked at his work, and thought, “Oh, well, I could do this.” He was really someone who always wanted to be front and center. He was always moving forward and trying to be the hippest guy there was.

JSYou could make the argument that some kinds of painting and some forms of music are improvised, whatever “improvised” might mean to different people. I don’t think an audience can always tell the difference. There are people who write music that sounds improvised; some play with physical gestures that look like they’re improvising. Do you think of yourself as an improvising painter?

SWWell, I don’t start off with any kind of color idea in my head. I never know. That’s why I use the same format; I can live off of it. Once I put a color down, that color will let me know the next color. Similar to music, you know, how a player can play and then they’ll inform the other player and then they’ll come in. They’ll see space and they’ll think, “Okay, I can come into this space.” It’s a conversation. For me, it really is a color conversation.

JSIt seems to me that it might be difficult to know how people perceive color. I assume that most people can see the difference between colors, but the way they group or relate to those colors may differ. I worked with an anthropologist at Yale who’d spent much of his life among isolated people in the highlands of the Philippines. They only spoke of four colors, and included all the different colors they saw within those four. There’s something similar in music: some studies of musical sound in the United States show that many people hear an ascending line of music as descending.

SWProbably so. I don’t think I have great ears. Or maybe I do have great ears because I do everything by sound. I think a lot of Afro-Americans think about sound in a central way. I think it really comes out of Africa, where sound functions as language. If you think about the talking drum in Africa, it’s language, but the Europeans couldn’t hear it outside of their preexisting ideas about sound and music.

JSDon’t some people speak of certain colors in terms of volume? Like red?

SWYeah, that’s what you would say. “Oh, you can’t wear that, that’s too loud.”

JSOr they speak of a color as being softer, say “a muted green.” So, colors do, in the way we speak, have sound and volume.

SWWhen I paint, I want to have that sound. The sound informs me, though I don’t think about it that way. Early on in my career, I lived in one place and painted someplace else. I would get up, I would look at art books, Cezanne or something, and think about that work. Then I’d listen to music for an hour or so and then I’d go paint. When I got to the studio, I had a little tape and I’d hit the tape and have music on. I often paint to Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew [1969]; it’s very important to me. I’ve always been open about that, but I remember that David Hammons told me, “Don’t tell people that. Don’t let out your trade secrets” [laughter]. But it doesn’t make any difference.

JSArtist Adam Pendleton said that you “know how to break down visual order to imbue it with music.”

SWThat’s probably true. These are things I probably do that I don’t really think about.

JSJazz and painting are in other ways analogous: in the twentieth century, new forms of jazz appeared about every eleven years. There was ragtime, boogie-woogie, swing, Latin, bebop, cool, and so on. These continual evolutions were followed by arguments between their advocates. Bebop was maybe the most disruptive of musical innovations because it broke a number of jazz rules and a lot of people hated it. There’s a certain analogy there in painting, where you have the same kind of generational thing. Some people hate it, some others like it, and critics try to pick out the winners.

SWYes, I think that’s true. Because America was so into trying to keep this country lily white that artists, musicians—those people were really, really radical people. Whether they were white or Black, they were radical people. And radicality requires exploration, change, experiment—

JSAnd these innovators dressed to show they were different, dressed as artistes: berets, horn-rimmed glasses, large flowing bow ties.

SWAbsolutely. And those forms and styles came about—you know, like Billie Holiday, they came out of brothels. They didn’t come out of where they should come from, you know what I mean? They weren’t legit. If you were socially correct you were listening to gospel music. This music was really coming out of all the wrong places, and it was total freedom. The thing about that music is total freedom: to think and be and discuss things that you couldn’t discuss in words.

There’s something there that I look to. I think Herbie Hancock said one time that he was playing with Miles, and he played the wrong note, and Miles looked at him, but without any worry; he just adjusted immediately. There aren’t any wrong notes. I was realizing when I was painting, there aren’t any bad days. A bad day is a good day because you’re trying to get to another level, you’re trying to get to something else.

I heard Ornette Coleman once in San Francisco, and all these people came out, and when Ornette started playing, he was there immediately. There wasn’t an introduction, it was like, noise—woom! And people fled, people just left. Because there was no buildup to it, it was immediate, and it was just “wow.” I think it’s like abstract painting. You have to bring a lot to it; there aren’t words or a conventional story. There’s a story, but it’s a much more open, complicated path to the story. That’s a big thing about it.

JSJordan Belson said of his painting, “It’s not nonobjective, I just don’t know what it is right now.”

SWThat’s the whole thing. Can you handle that you don’t know what it is? But we don’t really know what anything is, so that’s okay.

JSWhen it came to what was called free jazz in the 1960s, some musicians began to play without concern for many of the rules of the music, raising the question of whether anything is ever completely free, free to do anything. I mean, is such a thing possible?

SWI think it is to a certain extent—I mean, the last of the John Coltrane albums are hard. Even for me, Ornette’s record Free Jazz [1961] is difficult to listen to. Some of it, I think, is more for musicians. Likewise, there are such things as painters’ painters.

JSI recall free players in the 1970s saying, “It’s easy to get started, it’s hard to stop. You don’t know where to stop and how to stop.”

SWI would think that’s true. I would think that’s true writing a book [laughs]. You write a novel, it’s hard to figure out how to maintain that flow, that rhythm, all the way to the end. You have to know when to stop. If you’re playing music, it’s communication. There’s that one concert where Coltrane goes on and on and on and on, and the audience is clapping and whistling and going crazy, and Miles is like, “When is this guy going to stop? Get that goddamn horn out of your mouth.”

JSYou’ve said, “Getting the rhythm of a painting is really important to me. There’s no beginning and no end, and I can shift around in it from any spot.”

SWThat’s true, because if I tell people before they encounter the work, “There’s no beginning and no end to these paintings, you can go anywhere in the paintings,” they have more sustained interactions, they allow the rhythm to work naturally. I always wanted to make paintings that would be something you would always come to and they’d be different all the time, you could live with them.

JSYou’re having a large exhibition at the Buffalo AKG Art Museum. Can I ask about the title, How High the Moon?

SWWhen they asked me for a title for the show, that’s what I came up with. I don’t know how I got to that but I thought it was wide open. I think about that recording of Ella Fitzgerald in Berlin where she forgets the words and just goes off. She goes, “There’s a song / Could be wrong / But how high,” and then she’s just scatting. And then she talks and says, “Well, they probably don’t know what I’m saying, but I guess it doesn’t make any difference,” and it just goes on and on and on. It’s just perfect—to go from the clear song to just scatting, and she stays in rhythm the whole time. I just love the total freedom of that.

JSDo you think she really forgot the words, because they’re pretty simple?

SWShe says she did. Or maybe she says she got them wrong or whatever. And the thing about it was, that record was one of my mother’s favorite records. As a kid, I used to love it. When I thought about this show, it’s sort of . . . how high the moon, how far I want to get out there. Still trying to get out there.

JSWhen you title paintings, do you intend people to get a meaning from the title?

SWI think titles are a way of figuring out who I am or where I come from, what my concerns are. It’s like an opening.

JSSo when you don’t title—

SWNo, I always title.

JSYou always do?

SWAlways.

JSWhy do some of your catalogues say “Untitled”?

SWWell, the early ones I couldn’t title, because I didn’t know what they were. So, the early paintings aren’t titled. Titles started in the ’80s.

JSDo you remember why you started doing them?

SWEarly on, I wasn’t showing that much, so it didn’t make any difference whether they had titles or not. I was moving from painting to painting pretty quickly. I’d paint a painting, put it on the wall, paint a painting, put it on the wall. No one was really seeing them so they weren’t brought out. But once they started going out into the world, I wanted to have them have names. It’s a real burden, to tell you the truth [laughs].

JSYou once said that some of your favorite painters were Joan Mitchell, Mark Rothko, and Jackson Pollock. They were all three very interested in music.

SWI guess they probably were. Because they were part of that downtown bohemian world.

JSComposer and musician David Amram told me that Joan Mitchell had a collection of African records back when you couldn’t find African music in the United States.

SWProbably so. I mean, she was a wild woman. That milieu, they might do other stuff, but by the end of the day, they would end up at Slugs’ or the Five Spot or something like that. They were really adventurous people. Their work shows how adventurous they were and how willing they were to stretch out and not be classified as this or that or the other. I mean, they were my kind of people. I could come out of that tradition.

JSYou’ve spoken before about your interest in quilts, be they Amish, kente cloth, or the quilts of the women of Gee’s Bend, Alabama. It seems to me that Black quilters improvise like crazy.

SWOh yes, and that scares people, because you get to Barnett Newman and all these people clearing things out, abstraction, Minimalism, and then you have these women in these little shanty houses in Mississippi making unbelievable quilts, and you think, “Damn, that’s better than a Barnett Newman,” and how’d they do that? Is it a mistake, or is it just . . . audiences have a hard time thinking of them as intellectuals.

JSOne collector of quilts asked some of the makers why on some pieces everything seems to be of the same length, and then suddenly, one of the strips is longer. One quilter said if they were the same length, it wouldn’t look good. Another person said, “I don’t measure it because that’s not fun.”

SWYes. I would say there are a lot of things they do that intellectually they don’t have the words to express what it is, or what the theory is. I would think that if someone came to talk to them, they wouldn’t tell them anything anyway. I think of my mother: she wouldn’t tell people much. She wouldn’t trust people. If someone white came to the house, she wouldn’t trust them. She might know but she wouldn’t share.

JSWhat surprised me about kente cloth was seeing that the craftspeople would sometimes weave words and letters into them.

SWThey say, during slavery in the US, if someone put a certain fabric on the window or hung it over the line, that indicated that it was time you were going to escape. There were messages. So it’s a whole kind of language, just like jazz or some painting. And again, people have a hard time believing that they’re intellectual simply because it’s not spelled out in the typical way.

JSTo return to the question of free jazz, many of those musicians were actually resorting to old techniques, like riffing—repeated musical figures behind a soloist’s melody—and call and response, so the freedom was often more about discovering older patterns and using them in new ways rather than breaking rules. But there are those artists who believe that the more restrictions on the work, the better the art. For you, that would be the grid, right? The grid will make the painting work?

SWWell, I respect the grid, and I think about the ancient world’s use and artistry with it. But I don’t see my paintings as grids. Other people do. Really, I just stack the color. It’s good drama to have the color that shouldn’t behave in this kind of setup actually behave. It’s almost like having black and white, warm and cool—these things are really where the action is. And it’s endless. It’s like numbers.

So that’s how I see it, but it works for me. Luckily, I had time to develop this manner of working, because for a long time no one paid attention to me. I had a lot of freedom to dream. I always say now with the young painters, they don’t have dream time.

I’m really enjoying your Billie Holiday book right now [Billie Holiday: The Musician and the Myth, 2015], but I’m excited to get to Miles [So What: The Life of Miles Davis, 2002]. Then I’m going to round it off with Sun Ra [Space Is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra, 1997].

JS You could use some of Sun Ra’s stuff as a painter.

SWOh, I did. I did a painting called The Vibrations of the Day [2022].

JSReally?

SWYes, from Sun Ra. I was quoting from somewhere—he was asked about the work and he said, “Well, it’s the vibrations of the day.”

Stanley Whitney: How High the Moon, Buffalo AKG Art Museum, New York, February 9–May 26, 2024

Stanley Whitney: Dear Paris, Gagosian, Paris, January 10–February 28, 2024

Artwork © Stanley Whitney