Gisele Castro has dedicated her career to creating and leading organizations that focus on ensuring equity in justice for court-involved youth. She is the executive director of the New York City–based nonprofit exalt.

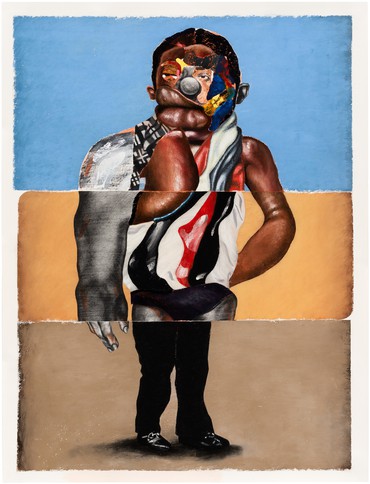

In his composite portraits derived from sources both personal and found, Nathaniel Mary Quinn probes the relationship between visual memory and perception. Fragments of images taken from online sources, fashion magazines, and family photographs come together to form hybrid faces and figures that are at once Dadaesque and adamantly realist, evoking the intimacy and intensity of a face-to-face encounter. Photo: Kyle Dorosz

Nathaniel Mary QuinnWhat a year, huh?

Gisele CastroWhat a year, that’s for sure.

NMQHow’ve you been doing, Gisele?

GCYou know, I’m going to say great. We were recently selected as a finalist for the Nonprofit Excellence Award, presented by Nonprofit New York. There are more than 45,000 nonprofits in New York City, 20,000 in Manhattan, and exalt made it to number two, all the way up.

NMQThat’s great.

GCWe were also just selected as one of seven organizations in the United States to receive an inaugural grant from the new NBA Foundation, and in October we were chosen as a service provider for New York City’s Alternative to Incarceration program by the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice. Governor Andrew Cuomo has slated us as an organization best positioned to serve in the implementation of New York State’s Raise the Age legislation too.

But we should start by going back to our foundation and when we got into it.

NMQOkay, let’s see. You and I first met at cases, the Center for Alternative Sentencing and Employment Services, when you were part of that program’s leadership. After some years you left to join exalt, and you played a pivotal role in putting together a team of teachers and others who would serve these young people from dire conditions and rough neighborhoods throughout New York City. That’s when I started at exalt. That was around 2010, right?

GCYes.

NMQOur primary goal was to find ways to help these young people to stop interfacing with the criminal-justice system, and we thought, Well, let’s definitely have an educational component, based on a curriculum that we develop. That was number one. Second, let’s help them to deal with their personal issues and family histories and try to unearth any hidden problems that they have yet to confront. And third, let’s put them in internship programs so they can make money working in legitimate industries that are anticrime, to help open their minds to other possibilities and so that they can feel empowered.

You taught me everything about how to navigate the courts. We would try to negotiate with the judge: “Sir, we understand that this young man or young woman broke the law. We get that. We just don’t think that the punishment that you want to levy against this young person is commensurate with the crime. Give this young person to us. We’ll work with them. We think we can help this person get on a different track in life. They don’t have to go to Rikers Island. Instead, we can really help to encourage them to transform their lives so that they can go on and do something else instead of doing six months to a year for jumping a turnstile.”

GCWe work with young people ages fifteen to nineteen, and we hold ourselves accountable to three big pillars: education, employability, and criminal-justice avoidance. The program starts with a six-week preinternship class—we’re preparing these teenagers for the world of work, but the first session is about the school-to-prison pipeline, the second is about mass incarceration, and so on. We’re teaching these young people about systemic challenges and asking them key questions. What we do with our young people is activate them. It’s about creating a vision, a pathway, a road map.

And your classes, Quinn, were phenomenal. Having a group of young people who read at a sixth-grade level—these are sixteen-year-olds—and to have them bounce back and become exceptional scholars is substantial. It’s not that they’re not capable or don’t love learning when they enter the program, it’s that our school systems have failed them over and over.

NMQWe’ve learned, of course, that there’s a strong correlation between illiteracy and criminal behavior. Most people who go to jail have difficulty with reading and writing. That’s important to note, because in order to succeed in the mainstream world, you have to be able to decode the language of the mainstream world.

GCYou do.

NMQI’m going to tell you something: I can’t think of anything else that has given me the kind of fulfillment that I experienced in helping a young person to read and write. There was one young man who couldn’t read—

GCI remember. I remember.

NMQAnd when he read his first two or three sentences, I cried. He cried. And I said, Now listen to me: someone can take your sneakers, someone can rob your house, but no one can take your education from you. No one can steal that from you. That’s yours forever.

That was at cases and the class was called “Literacy Lab.” Years later I made a work called Literacy Lab [2019]. Just days ago that work was gifted to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC. But it was made in direct response to my experience working with kids at cases and exalt. That experience had a major impact on me.

GCThe first thing that would always happen in your class, and still in any of our classes, was the burst of laughter. The first point of joy. A lot of us don’t have joy, right? I think we hold on to so much burden. But we used to walk in and there’d be laughter bursting out of the classes.

I have to mention some of the young people you worked with at exalt. These are young men and women who once upon a time were profiled as people who couldn’t succeed. One young woman, Ayanna Fox, from exalt’s cycle 40 in 2012, graduated from high school, then from college, and now she has her master’s degree and is working full-time for New York City’s Administration for Children’s Services. She just bought her first home, during the covid crisis.

NMQShe bought a house?!

GCAnother student graduated with her GED in 2017, and now she’s at college. We were able to get her a $20,000 scholarship. You know, we understand that our young people are the first in their families to break these multiple barriers. And many of your kids had their cases reduced, vacated, and then many years later they’re so successful.

NMQThese were students who didn’t believe in the prospect of going to college. They didn’t even think that was available to them. Where I live, in Brooklyn, I see some of my students now in the neighborhood. “What’s up, Mr. Quinn, how are you doing?” They recognize me. Of course they’re older now, twenty-six, twenty-seven years old. I say, “What are you doing now?” “Oh man, I got a job. I work in my uncle’s business.” Or “I’m a record producer.” Or “I’m in school to study law.” They’re doing all these great things. When I met those kids they were facing jail time.

What we do with our young people is activate them. It’s about creating a vision, a pathway, a road map.

Gisele Castro

GCAbsolutely. When we look at the data for New York State, a young person who has been arrested or convicted of a crime has a 40 to 60 percent chance of recidivating within two years. Our data shows that two years out, 95 percent of our young people are not reconvicted of a crime. Our model is very robust.

We ask our young people early on, Where do you see yourself in five years? They often say, Not here in this world or incarcerated. Then at the tail end of the class, when we’re prepping them for their alumni phase, we ask them, What is your fear for yourself and your hope for yourself? No longer being here, or incarcerated, that’s their fear. This is a four-and-a-half-month model. When I give people this overview, they typically say, What’s the magic? There’s no magic but there’s rigor. We have an organization that’s 90 percent led by people of color. I’m still one of the few Latinas running an organization that’s dealing with young people involved with the justice system.

In terms of the long-term impact, we’re seeing that our young people’s cases are closed, they’re safe, and then in turn they’re keeping New York safe, because the number-one referral is a young person who’s graduated from the program; they’re referring their friends. It costs $236,000 a year to incarcerate a young person. The cost for our organization to provide services to a young person is $10,000 a year.

Quinn, you would always say to me, Gisele, do you know that this is a soulful work? This is a work for the soul.

NMQIt’s spiritual work.

GCYeah, beyond cerebral. That’s true.

NMQI love reaching young people and encouraging them to believe in something they did not believe in before. That’s the job of a teacher working with so-called at-risk youth: you need to make the classroom experience more alluring and more appealing than the communities from which they come, to compete against their surrounding environment and whatever dark cloud may exist. In order to attack that, you have to operate from a spiritual place. You can’t just be guided by what’s in your head, you’ve got to believe it. Because if you believe it, that makes it more likely that they will believe it.

GCWhat you’re highlighting is the reason I said you had to be the team leader, the heart of the organization: when we brought in teachers, we were asking people who, mostly, had just come out of universities, You can’t be so cerebral, you need to connect.

For so many of the young people we serve, the systems have failed them since they were a tender age. Then they come into our organization and see all this thriving energy and movement toward life. When they walk in, the first thing is there are no metal detectors.

NMQNo metal detectors, that’s right.

you have to operate from a spiritual place. You can’t just be guided by what’s in your head, you’ve got to believe it. Because if you believe it, that makes it more likely that they will believe it.

Nathaniel Mary Quinn

GCIn 2017 I launched a strategic plan to scale up, to saturate the five boroughs. My goal was to triple the previous budget, triple the number of youth served, moving out of Brooklyn to 17 Battery Place in Manhattan. We hired graduates of ours who were interns to work with DBI Projects to design the new space. It’s beautiful and it’s a thriving learning environment. The classrooms are named after Angela Davis, bell hooks, Michelle Alexander, Bryan Stevenson, Julia de Burgos—all of a sudden, it’s like this space is being claimed for them and they can move around. There are beautiful lush plants. And you think about a young person who probably just left public housing walking into a building overlooking the Statue of Liberty, which is symbolic of freedom.

This year we launched seventeen virtual classes, and I will invite anyone to our graduations; they’re just so moving. I would say they give anyone life.

NMQYou did seventeen virtual classes this year?

GCSeventeen. We pivoted on March 9, even before New York State was put on pause. The situation around covid is dire. The courts aren’t designed for a global pandemic; a lot of cases were suspended. And a young person who feels confined is prone to so much. Court involved or not court involved, many of our teenagers during the covid pandemic are disengaged. A young person with the burden of “I may be facing time” could easily give up and slip. So this is what we decided to do: we were able to get not just laptops but also data plans for our young people. For forty-five families, we were able to secure $500 each in cash assistance. Then we brought in the Black Googler Network to make sure they understood how to navigate and use the digital tools for virtual engagement. We also asked all of our intern providers—at this point we have more than one hundred—“Can you create research projects?” To stimulate the mind. And we’ve kept our young people going and thriving and continuing to meet with great success.

We also understand that we have to go deeper; it’s our moral imperative. We know—we have all the data—that communities of color have been the most impacted by covid. I think we have an opportunity to change that, and if we do it with young people who are court involved, we’ll be doing it for so many more. When young people face potential incarceration, there are so many others—mothers, fathers, grandparents—who have that burden as well.

Quinn, when young people would come to us through a referral, you would meet them and give them an acceptance letter and it would say, “Congratulations, you have been accepted to exalt.” At the end, the same thing: “Congratulations, you have just graduated from this organization.” And as you would say, those were the first certificates of any kind that they had ever received. Now whose problem is that? It’s all of ours. It’s not just for exalt to address, it really is a call for everyone to say, That should never happen. Not on our watch, not in New York City.

NMQAs a board member, I will say as clear as day: my fantasy is always for exalt to have more money, because with that money we could do more of the things we do for our youth. Simple as that. So if you really speak with conviction about helping those who are less fortunate, then take out your checkbook, write a check, send it to exalt, and exalt will take it from there. The money will be used responsibly and in accordance with the needs of exalt in its outreach and its work with young people. This organization requires money to survive. And exalt is saving lives.

GCMy big ask is for people to understand that supporting young people in internships, giving them access, is important. We have a lot of work to do but we’re excited, we’ve geared up, and we have more to come. We’re closing up 2020 by launching a new strategic plan, and we have a tagline for our end-of-year campaign: “Youth justice can’t stop. exalt won’t stop.”

To learn more about exalt and how to support exalt’s programs, please visit exaltyouth.org.