Michael Cary organizes exhibitions for Gagosian, including eight Picasso exhibitions in collaboration with John Richardson and members of the Picasso family. He joined Gagosian in 2008 after six years working with the late Kynaston McShine, then chief curator at large at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Clive Smith

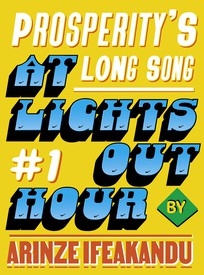

The Paris-based writer William Middleton is the author of Double Vision, a biography of the legendary art patrons and collectors Dominique and John de Menil, published in 2018 by Alfred A. Knopf. He has contributed to such publications as W, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Architectural Digest, House & Garden, Departures, Town & Country, the New York Times, and T. Middleton’s most recent book is Paradise Now: The Extraordinary Life of Karl Lagerfeld published by HarperCollins in February 2023.

Michael CaryYou’ve written two Francocentric biographies: Double Vision, about the de Menil family, published in 2018, and Paradise Now, about Karl Lagerfeld, which will be released later this year. I can see, here on Zoom, that you’re in Paris as we speak. How did your Francophilia begin, if I can phrase it that way?

William MiddletonWell, I’m from Kansas. I had a formative teacher in high school, my advanced-placement English teacher, and she was focused on French literature, so I was engaging in that canon from a young age. I think that’s the beginning of my fascination with France. And then, at the University of Kansas later on, I had a little map of Paris that I found at a travel agency; I kept it for many years and treasured it. My adoration was always from afar until I first went to France, for Christmas and New Year’s in 1989–90. I was living in New York but I immediately felt the need to live in Paris, so ten months later I moved there, remaining for a decade.

Then in 2000 I moved back to New York—and I love New York, I’ve lived there many times and I’ve always worked for New York magazines and New York book publishers. Wherever I am, I’m always connected to New York—but leaving Paris, I immediately felt that I had made a terrible mistake. In the end, it took me nineteen years to get back! But these things happen for a reason, and the silver lining was that coming back to America prompted the de Menil book. I moved back to work for Harper’s Bazaar and I went down to Houston to do a story on the city. Before I even headed there, I knew that I wanted to look into the de Menil family. In 1986, there had been a cover story in the New York Times Magazine on Dominique de Menil and her five children. It was called “The Medici of Modern Art.” I thought the family’s connection between France and Texas was intriguing, so I filed it away.

I went to Houston for the first time in the fall of 2000. Dominique de Menil had died a few years before and there was interest in a biography. I wrote a book proposal and had a contract with Alfred A. Knopf and the editor Shelley Wanger. For many years I’d been writing magazine-length features and I wanted to find a project that I could really sink my teeth into. In fact, in 1998 I did a big story for W on Yves Saint Laurent, for the house’s fortieth anniversary, and I had the possibility of writing a biography on Saint Laurent. But I never fully moved forward on it because frankly I felt like there was so little there that was relevant to life today, to the life of people around me. It put a block on the project—one that, interestingly, I didn’t encounter with this new book on Lagerfeld. Karl has always felt relevant to me; he’s always been connected to what’s going on in the world.

MCSo you saw Karl as a less rarified figure than Saint Laurent?

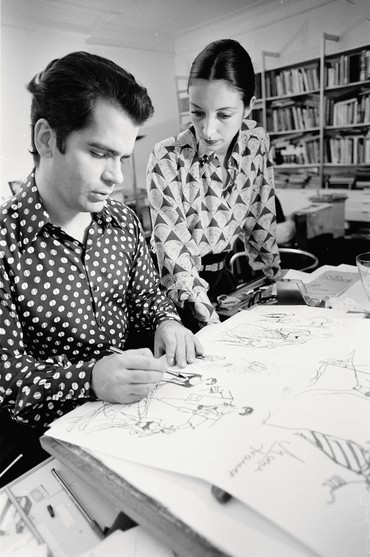

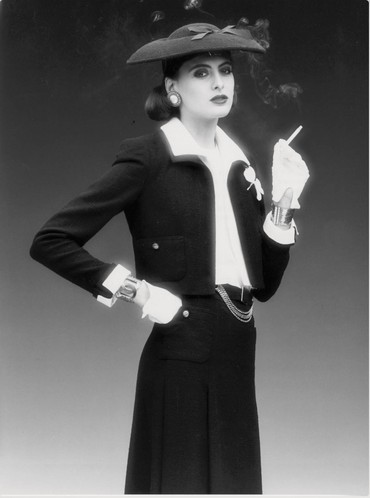

WMAbsolutely. I met Karl in January of 1995, when I was working for W and Women’s Wear Daily. From there we had a good working relationship that developed into a genuine friendship. I was in no way his best friend or anything like that, but we had a friendly rapport and he was somebody I always admired because of his connection with the culture of his time. He knew everything that was going on in terms of cinema, architecture, music, art, everything. I remember thinking at the time, and I’ve revised my thinking a little on this since, “There may be others who are more important in terms of fashion but Karl is superimportant in terms of the culture.” Now that I’ve done all this research on his career in the ’50s and ’60s and ’70s, I’ve realized how important Karl was in terms of pure fashion, even before he got to Chanel. Everything he did during the last two decades of his life was incredibly significant in terms of fashion—what he did with H&M, what he did with Fendi, what he did in terms of fashion photography, what he did redefining the fashion-week spectacle.

MCYou make the point several times, and Karl does himself throughout the book in quotes and anecdotes from friends, that he’s not interested in retrospective. It’s the present, it’s what’s happening now. Everything past is past, why bother with it? But there’s also this contradiction, because he’s obsessed with the eighteenth century and studies history voraciously.

WMI always felt like that was a little disingenuous of him to say that he was only focused on the present or the future. He had an amazing grasp of history and the development of aesthetics; it was just his own history that he didn’t want to focus on. There’s a moment in the book where his colleagues, including Amanda Harlech, are working on staging a museum retrospective in Germany, and he’s happy to work on it, he plays along, and then it comes time for the exhibition to open and they want him to attend and he gets furious. Where so many designers want that consecration, want people to be admiring their past work, he saw any focus on his past as funereal.

And this is where the title for book, Paradise Now, comes from. Karl sat for an incredible number of interviews throughout his life—these were critical resources in the creation of the book—and in 2014 he did a radio interview with this brilliant French journalist Augustin Trapenard. He’s a serious cultural journalist and he was pushing Karl on this whole idea of posterity, and Karl was like, “Posterity, you know, I don’t care. I just don’t care.” He’s like, “It won’t do anything for me. It’s today that counts. Paradise now.”

MCThat attitude must have presented some obstacles for you as a biographer. While he was larger than life and participated in many public forums, giving interviews and so on, he didn’t leave the resources that are so often key in these projects. He doesn’t have heirs. He didn’t keep a diary. What are the implications of that? I’m thinking, as an initial example, about the decisions you had to make around depicting his relationship with his mother. While he certainly revered her, she’s surrounded by many mysteries, and after she moves to Paris to live with him, she’s almost like this spectral figure. When you speak to Karl’s friends, even if they saw her, they don’t know anything about her—she was simply a woman wandering through the house while they were having lunch. And then when she dies, it’s as if the door is closed and it’s never mentioned again. Keeping in line with his focus on the present, she was immediately relegated to the past.

WMA lot of the quotes that I use from Karl about his mother came in later years. He talked about her a lot, but you’re right, she’s not easy to locate as a fully dimensional person. I had to approach her obliquely. Amanda Harlech recounts talking about Karl’s beloved cat Choupette, and she says, “Beautiful, withholding, pampered: it’s your mother.” And he’s like, “Exactly!” With direct references to her from Karl, it’s tricky, because I think some of the comments he has her saying sound suspiciously close to his own voice. Is that because he’s like his mother, or is he spinning that for effect? So, in general, I had to approach that material with caution, instead focusing on real material evidence and recollections of more impartial observers.

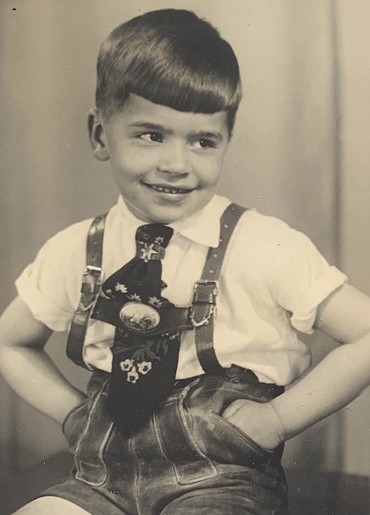

Luckily, I discovered this incredible notebook from 1954 at a Sotheby’s auction that proved revelatory in terms of understanding her. As I detail in the book, the notebook had all these press clippings and notes and drawings related to Karl’s winning the Woolmark Prize in 1954, which really jump-started his career. The auction records had this listed as a work by Karl, which I found odd, given that Karl wasn’t likely to hold onto something so retrospective. It stayed on my mind for a while, and then I was able to speak with two people who knew Karl very well, Caroline Lebar and Sébastien Jondeau. Sébastien immediately clarified, saying, “Oh, that was his mother who compiled and kept that.” Of course it was his mother’s! It’s her handwriting. It’s in German. He sends everything back to her in Germany and she puts the whole thing together. And I think that’s not only revealing of the facts of 1954, when Karl won that prize, but it’s also superrevealing about what she really thought about her son: this was someone who was very proud of her son. Karl always tried to give the impression that she wasn’t. He quotes her saying something like, “It’s good that you’re not very ambitious, since you just want to be a fashion designer,” right? The truth is much more interesting.

Piecing together the details of Karl’s life was a radically different project from the research for the de Menil book, because the de Menils had an incredible archivist impulse long before they founded their museum. They kept all their correspondence. In the family archives, Dominique de Menil had not only her letters from her family but she’d recovered her side of the correspondence as well. A biographer’s dream.

MCAnd Lagerfeld seems like it’s the absolute opposite, right?

WMExactly. He did not keep information like that.

MCI’d love to speak about Jacques de Bascher, who plays such a key role in the first half of the book. Lagerfeld’s relationship with him was obviously an intense one, but there are a lot of lingering questions. In terms of writing about Karl’s sexuality, there is this duality of guardedness on one side and unapologetic flaunting on the other, especially for 1970s Paris. There are several points in the book where people insist that Bascher and Lagerfeld had no physical relationship and it feels a little bit like the lady doth protest too much [laughter]. How did you navigate the queerness of Lagerfeld’s life?

WMYou’re absolutely right to point it out as a contradiction, because on the one hand, Karl never hid his sexuality. He never pretended he was straight. But he also wasn’t militant. It’s a funny contradiction, and Karl himself said that he was a bit of a puritan. I don’t think it was an internalized homophobia, but there was a puritanism at play, most definitely. And yet he loved looking at and taking pictures of naked men. I think it’s another of those instances of, How can you really know someone’s truth? The only thing that I can do as a writer is to say what I know, what I’ve discovered, say what other people have said, and then readers can make up their minds. With Karl, that opacity and complexity make for a more interesting subject.

MCYou open one of the chapters with a quote where he says, “Essentially I am a Calvinist attracted to superficiality.”

WMWhich again is not fully true, do you know what I mean? That he’s a Calvinist, yes, but attracted to superficiality—well, yes, but also incredibly deep. There are some statements that he makes that are interesting and not exactly true.

MCIn both of your books, I notice that you consider details of how someone lives—the seemingly superficial, the materiality of ordinary objects, the way furniture is arranged, how someone greets a visitor—as important as what that person does. With the de Menil book, you go into so much detail about the opening of the museum, like how the napkins are going to be folded. It’s a beautiful detail that tells us so much. Where does that sensibility come from for you? Is it that you come across these details and they fascinate you? Are you searching for them?

WMI look for them. Detail makes for a good biography. In any life, I’ve found, the littlest detail can be unfolded and opened in revealing ways. But more generally, I find that the most compelling writing conjures images. The reader must be able to experience this life visually, especially for a subject as image-obsessed as Karl was.

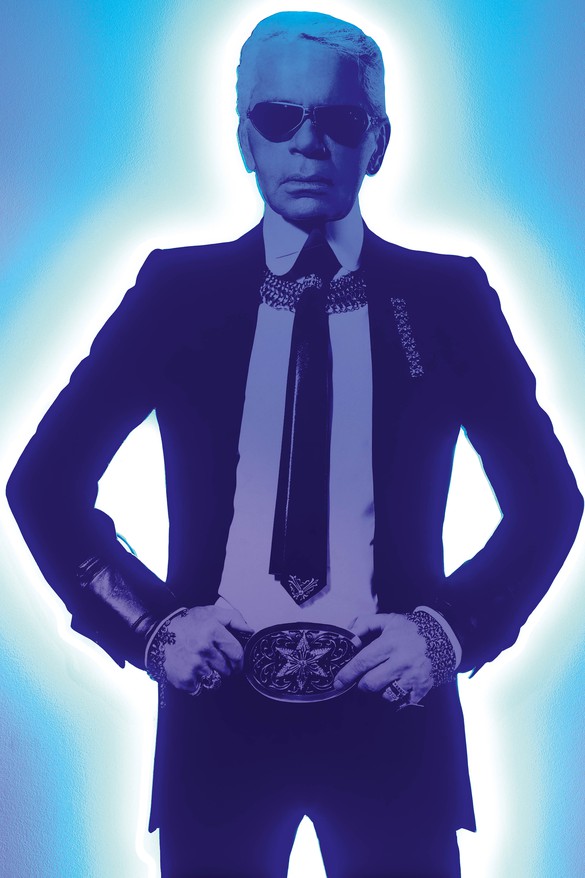

MCAnd Karl also creates an image of himself, especially at the end of his life. After he loses the weight, he becomes this avatar of himself. How did you use this extensive visual record of him to work on the book?

WMThere are so many images. I can’t tell you how hard it was to do the photo research for this book! There were so many amazing pictures of Karl that we couldn’t include them all. Even if we couldn’t include them in the book, reviewing as many photos and videos as I could was invaluable. There’s one video that I found in archives in Texas, from his trip to Houston in 1979, when he was greeted by the marching band and pompom girls. That whole moment—the limousine with the steer horns on the front, and the horn plays “The eyes of Texas are upon you”—it’s just bananas, right? Those materials make for some of my favorite moments in the books.

MCThat kind of excess and spectacle is a motif in the book. I’m thinking about the fact that Karl spent $1.5 million a year sending flowers to people. Everything is fantasy on a scale that is unattainable, and yet somehow this man attained it. You do a great job of developing that grandness in its exponential growth throughout his life, and I wanted to ask you how you thought he was able to maintain this level of achievement and productivity for so many decades.

WMAs you probably know, a lot of creators never get into the position to be able to concentrate fully on their work, or to have the best kind of conditions for their work. Karl made sure that he always did. He would get up in the morning, he would get ready, his pads were there, his pencils were there, he just had to sit there and design. He came back from the house, everything was ready. Silvia Venturini Fendi said she thought one reason their relationship lasted so long was that the Fendi house gave him the means to do everything that he wanted to. But it was the same way at Chanel and at every house he worked with: he always had this extraordinary kind of support so that all he had to do was work.

MCWhat do you think prompted people to give him that support? Do you think it was something he demanded?

WMWell, I think he earned that—through the work he did and the success he had. If he hadn’t been successful he wouldn’t have continued to get that. But also, Karl was equally generous in return for all the support he received. He didn’t take it for granted. There’s a story, which didn’t make it into the book, told by Anita Briey, who worked with Karl at Chloé and then ran the Lagerfeld atelier. Karl had an annual lunch at his apartment for the Lagerfeld team. Each year, he would give them a little Chanel bag. And Anita Briey said to him, “You know, there’s someone here and she has received a bag—it’s so beautiful—but she’s a lady of a certain age, and it’s red, and maybe that’s a little too much, and do you think it might be possible to change?” And he replied, “Oh, absolutely,” and he got one that was navy or black and he gave it to her and she started to give the other one back, and he was like, “Oh no, keep both of them.” That’s someone who knows how to treat people who work for him, how to get good work out of people. I think Karl was a good manager in that sense. The teams at the various houses who worked with him adored him. It’s fascinating because he has this image of being so harsh, but that’s not at all the impression that people in the atelier had. This was someone who loved his work and encouraged other people to do great work.

MCYou quote Alain Wertheimer, one of the owners of Chanel, saying that Karl was very, very nice, he just didn’t want anyone to know it.

WMAbsolutely.

MCIn the interviews you conducted, you get the sense of intense love and loyalty from a lot of the people in his life.

WMI once told him, I’ve rarely seen anyone who has a public image that’s so harsh, but when you get to know them you see that the reality is much warmer and almost touching. And he said, “Well, it’s better that than the opposite, non?” [Laughter] I love the fact that he was aware that it was a performance, that he was an avatar, as you said. There is an anecdote from the photographer Jean-Baptiste Mondino: he was getting ready to take some photographs of Karl, and as Karl was heading to the hair and makeup room, he said, “Time to go freshen up the marionette.” That’s someone very conscious of the effect that they’re having.

MCHe’s a marionette but he’s also pulling his own strings.

WMAbsolutely.

William Middleton, Paradise Now: The Extraordinary Life of Karl Lagerfeld (New York: HarperCollins, 2023)