Alice Godwin is a British writer, researcher, and editor based in Copenhagen. An art-history graduate from the University of Oxford and the Courtauld Institute of Art, she penned an essay for the exhibition catalogue Damien Hirst: Fact Paintings and Fact Sculptures and has contributed to publications including Wallpaper, Artforum, Frieze, and the Brooklyn Rail.

Solveig Øvstebø is an art historian and curator. Since 2020, she has been the executive director and chief curator of Astrup Fearnley Museet in Oslo, Norway, where she organized the first museum exhibition to survey the practice of Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme. Previously, she was the executive director and chief curator of the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago from 2013 to 2020. Øvstebø served as the director of Bergen Kunsthall from 2003 to 2013, developing the institution into an internationally renowned and leading platform for contemporary art in Norway.

AGI understand that Before Tomorrow has been a resounding success, which says a lot about the place that the Astrup Fearnley’s collection occupies in people’s hearts. What were your initial hopes for the exhibition?

SOAnniversaries offer the possibility to think about an institution—its role, and the collection it holds. It was an exciting opportunity for the cocurator, Owen Martin, and me to dig deeper into the collection to understand its points of departure and its paths during the past thirty years. Collections like the Astrup Fearnley Museet’s have their own stories, right? They have artists’ voices that have been heard more loudly than others. It was interesting to include some of these voices, while also including artists less commonly associated with the collection—to strike a balance between works of art often seen as pillars of the collection and the more unknown works, as well as new acquisitions that present new directions. So, in that sense you can say that the show was about searching for idiosyncrasy and diversity, rather than telling one story. We also revisited some of the works and installations from the institution’s exhibition history like Børre Sæthre’s massive installation My Private Sky from 2001. Also, Shirin Neshat’s video Fervor, from 2000, is given its own room in the exhibition—a work that was so relevant when it was made, and which again speaks to the current situation in Iran.

AGThe show offers a wonderful opportunity to reflect. How do you feel looking back, now three years on from starting your role?

SOAfter my farewell party at the Renaissance Society in Chicago on March 1st, 2020, I came back to Norway just in time for everything to shut down on March 15th. This was a couple of months before I was meant to begin my new role at the Astrup Fearnley Museet on May 1st—in the midst of the pandemic! It was manageable, though, and thanks to an incredible team we kept the museum open as much as possible and continued with the exhibition program as planned. Of course, there were times when the institution closed completely. At one point we even finished installing a show only to wait several months until we were allowed to open our doors.

My first project at the Astrup Fearnley Museet was with the American artist Nicole Eisenman, who made this amazing exhibition, Giant Without a Body. This was her first big survey in Europe, spanning works from 2006 to the present. It was such a massive and beautiful presentation, and it was nerve-racking to follow the restriction updates day after day to see if we could open or not. Luckily, we managed to open the exhibition in this little pocket of time, from May to September 2021, when the restrictions were lifted. Then Norway closed down again, and we had to wait. So, we worked on the next exhibition, which was with Norwegian artist Sissel Tolaas—her first institutional show in Norway. She turned the Astrup Fearnley upside-down! The whole show was about breathing, touching—everything we couldn’t do during the pandemic. For the work Liquid Money_2 (2021), we had a sauna outside, where visitors could sweat in the smell of money and then swim in the fjord to wash that smell off. It raised a lot of interesting questions regarding Norway’s offshore oil industry.

I believe every museum director would acknowledge that navigating an institution through a pandemic was challenging. However, it was also a period that encouraged us to contemplate the potential of museums. In many ways, this shared experience served to strengthen the cohesion within the team and positioned us to move forward. It prompted us to collaboratively explore innovative solutions and opportunities.

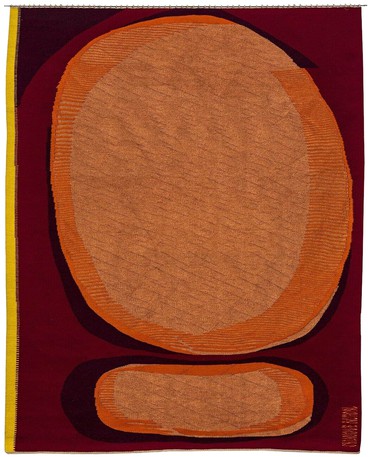

Over the course of these three years, I’ve had the privilege to work on several extraordinary projects. One particularly exciting moment was the realization that Hans Rasmus was one of the first collectors of the late Norwegian textile artist Synnøve Anker Aurdal. The museum owns some of her most important works, which prompted us to organize a major presentation in 2022. Aurdal was a trailblazer and played an important role in the emergence of Norwegian modernism. In her lifetime, she was often overshadowed by her male contemporaries, but today—when we look back at her extensive practice, which stretched from the 1950s through to the 1990s—it’s evident that her textiles influenced and inspired many Norwegian painters working in the late twentieth century. She was part of a group of artists that very much worked together. The Norwegian scene has recently become more aware of this history and is revising the way it is recorded. It was great to be able to make that first major presentation of Aurdal’s work.

AGSpeaking of Norwegian artists who have been overlooked in the past, you’ve previously mentioned wanting to celebrate artists beyond the familiar favorites, like Edvard Munch. Are there any particular artists on your wish list? Or areas of the collection you feel need to be strengthened?

SOFirst of all, it’s important to stress that we are very proud of Munch’s legacy, but it’s also important to make space, within a more official narrative of Norwegian art, for artists working in the present. We have great institutions in this country that are focused on historic artists and periods, but it’s crucial that we talk about what’s going on right now in Norway, not only in Oslo, but also in cities like Bergen, Stavanger, Trondheim, and Tromsø.

When it comes to new acquisitions, the Astrup Fearnley Collection has had a focus on American art for many years, but there is a need to include more and different voices from this scene to reflect how diverse and complex it actually is. For me, Kara Walker was one of the artists that I felt was important to include in the collection. In 2021 we acquired the film …calling to me from the angry surface of some grey and threatening sea, I was transported (2007), which I first saw at the Venice Biennial, and then the incredible paper cutout wall installation, THE SOVEREIGN CITIZENS SESQUICENTENNIAL CIVIL WAR CELEBRATION (2013), which is included in Before Tomorrow. We’ve also acquired works by Walter Price, Robert Grosvenor, and Nicole Eisenman, among others.

Works by artists based in or connected to Norway like Joar Nango, Mikael Lo Presti, Frida Orupabo, and earlier this year, Sandra Mujinga, have also been added to the collection in recent years. And the acquisition of Wolfgang Tillmans’s Concorde series (1997) marked a crucial reinforcement of photography as a significant medium within our collection.

AGI was wondering about the support for young artists in Norway. Is there an ecosystem that functions well in Oslo?

SOIf I’m honest, I would say both yes and no. Like any European capital, Oslo is expensive. Renting a studio and the general cost of living are high. At the same time, we’re fortunate that there is a state-funded system in place to support artists, and it’s robust compared to many other countries.

That said, I think it is important that we don’t forget about other institutional positions, including artist-run spaces, kunsthalles, and itinerant projects. They play a central role in developing the next generation of art practitioners and sharpening artistic discourse. We also need the magazines, the writers, and the art critics to continue building and maintaining a criticality in this environment. We’ve expanded the Norwegian art scene in quite a short amount of time with the creation of these huge institutions, but we tend to forget what is holding them up. I think “ecosystem” is a very good word here, because it means that if you take one part away, the whole system gets damaged.

AGAbsolutely. The contemporary art scene in Norway has grown tremendously in recent years with the new National Museum and the development of Tjuvholmen (Thief Island) and the waterfront. I’m interested in whether the public has come along for the ride? Is contemporary art an important part of the cultural conversation?

SOI think so. In the early 1990s, the scene was opening up, but it was a slow process. Then abruptly things changed. It was what Hans Ulrich Obrist later referred to as the “Nordic miracle” when, all of a sudden, impulses from abroad came to Norway, as well as other parts of the region, and catalyzed an emergent contemporary art field. At the time, the broader public wasn’t so familiar with contemporary art, but now, in many ways, it’s the opposite. Contemporary art has an enormous attraction for a general audience. I think it has to do with the influence of the government and the changing perception of culture, as well as the building of these incredible museums. Individuals like Hans Rasmus Astrup also need to be credited. When he opened the Astrup Fearnley Museet in 1993 it was with art that people had never seen before—it was shocking and weird and strange. This was the place where you went when you wanted to see something that was challenging and ambitious.

AGDo you feel the Astrup Fearnley’s collection reflects this change in taste or has helped pave the way?

SOI’m not sure if taste is the right word, but it certainly has to do with openness. The Astrup Fearnley Museet was established in Norway at a moment when there was a new way of thinking about art. Hans Rasmus presented his position in this shifting landscape on a major scale. He made a very significant contribution to the Norwegian art scene. I often told him this while he was alive, but I am not sure that he fully appreciated the role he played for the growth of contemporary art in Norway. For him, art was simply an important part of life and he felt it needed to be shown and experienced, not live in some collector’s home or be placed in storage.

AGWe need those collectors who have an unconditional love for art and a desire to share it without necessarily any reason, just a belief in its importance. I wanted to ask about the structure of the Astrup Fearnley, which I understand is quite unique?

SOIt’s a rare model because, in Norway, museums are mostly public. In that sense we are part of a family of institutions—like the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk; the Fondation Beyeler, Basel; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and the Henie Onstad Art Center, Oslo (one of the few institutions with the same model in Norway)—that originated with a desire to bring a private collection into the public sphere. All these institutions had founders who were not interested in creating a mausoleum to their art or persona but instead established living institutions that benefit the public context that they’re embedded in.

I had the opportunity to talk about the strategy of the museum with Hans Ramus before he passed away. That conversation was very important to me, and it also assured him that Astrup Fearnley Museet would live on as an institution for the public.

AGThat conversation must have been quite something. I wonder how he would feel about the direction the museum is heading in?

SOI hope and believe he would have been happy with it. Some of the programming he would have certainly loved while other projects he probably would have thought: “What is this? I don’t understand it, but I’m intrigued!” That is what he always did, even with his own acquisitions. He was excited to be challenged.

AGI suppose that’s what contemporary art does—delights and puzzles!

SOI think the most important traits that Hans Rasmus possessed were openness and a curiosity about the world. That is why we now have such an amazing collection. We’re building the Astrup Fearnley Museet on that foundation, so that we can continue being a relevant institution for contemporary art. Art needs to be at the center of this museum and to be given the time that it requires. I think institutions today need to focus on their core missions and try to manage all the competing demands that are placed upon them—which may not necessarily be about art.

Photos unless otherwise noted: Christian Øen

Before Tomorrow – Astrup Fearnley Museet 30 Years, Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo, June 22–December 3, 2023