Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at the Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames and Hudson in May 2021.

How long after the end of World War II did it take German and Austrian artists to reflect on their countries’ recent shared history? How long for the myths of Stunde Null or das erste Opfer to be challenged? Stunde Null, or “zero hour”—implying that Germany’s surrender marked a complete break with the past, a new beginning, as if nothing bad had happened—became something of a mantra in postwar Germany, while Austria successfully portrayed itself as Hitler’s erste Opfer (first victim) rather than a willing participant in Nazi crimes. Forty years ago, in 1983, I had an opportunity to find out answers to these questions. Living in Berlin at what turned out to be a vital moment both politically and art-historically, I had a growing sense that the art being produced in Germany and Austria was unprecedented, and as authentic as anything coming out of London, Paris, or New York.

As a thirty-something curator at the Tate Gallery (as it was then called), I had German art as my main responsibility. The director, Alan Bowness, was more sympathetic to the German school than his predecessors, and supported my efforts to represent it in the collection. He dispatched me to West Berlin to make contact with artists, dealers, and collectors and to brush up my German at the Goethe Institute, whose London director had kindly offered me a bursary. Until the fall of the Berlin Wall, in 1989, and the reunification of Germany a year later, Berlin was a surreal place. Governed by the Four Power Agreement of 1971, it was divided into sectors: its highly militarized eastern half (the Soviet sector) was the de facto capital of Communist East Germany (the GDR), while the security of its western half, where I was heading, was guaranteed by the presence of over 12,000 American, British, and French soldiers, each stationed in their own sectors. They had the right to send patrols into the Soviet sector, leading to some tense standoffs, while Russian troops in turn had the right to patrol the three western sectors. An island of democratic freedom, West Berlin was heavily subsidized by the Federal Republic (West Germany). I met up with a cousin married to a colonel in British military intelligence who sometimes invited me to dinner in their luxurious villa in the wooded suburb of Grunewald.

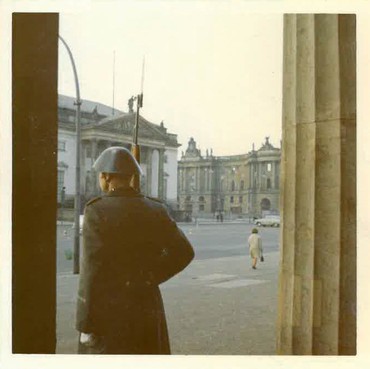

I had been to Berlin before. The first time was in 1967, as a fifteen-year-old, on a school trip to the Soviet Union, when we stopped for a day to sightsee in both halves of the divided city. We crossed from West to East in a bus through Checkpoint Charlie, observed by border guards from their watchtowers. In the evening we caught the night train to Moscow from East Berlin’s Friedrichstrasse station. What I remember most about that visit is the sad condition of many of the historic buildings in the East. You couldn’t get near the Brandenburg Gate for barriers and armed police; but in the nearby Gendarmenmarkt, the French and German churches and the Schauspielhaus, the magnificent theater designed in the 1820s by the great Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel, were still in a semiruined state, more than twenty years after the end of the war.

Ten years later, in 1977, I spent nearly a week in West Berlin touring the Council of Europe’s memorable series of exhibitions Tendenzen der zwanziger Jahre (Trends of the twenties), which I reviewed for the Times Literary Supplement. But I had never lived there long enough to get to know the city well. Now I discovered a lively art scene in Kreuzberg, a working-class district with a substantial immigrant population enclosed on three sides by the Wall. A favorite haunt of artists was Café Exil, which had been founded by the Austrian experimental writer Oswald Wiener and his wife, Ingrid; Exil’s chef and manager later took over the more famous Paris Bar in Charlottenburg. In the 1970s, Exil was the spiritual home of, among others, Günter Brus. Angered by the culture of denial and repression in his home city of Vienna, Brus had staged provocative “actions”—extensions of action painting involving white paint, self-mutilation, and bodily fluids—that earned prison sentences for him and his collaborators Wiener and fellow artist Otto Muehl, causing Brus and Wiener to flee to Berlin. I had already acquired works by the radical Vienna artists Hermann Nitsch and Arnulf Rainer for the Tate—and would later visit these artists in Austria—and on my return to London I added Brus to the list. Bowness had come to an arrangement with his trustees that he could buy up to a certain sum without reference to the full board, and the work of most contemporary German and Austrian artists in the early 1980s fell below that figure.

In the early 1980s the group known as the “Junge Wilde” or “Neue Wilde” (the young, or new, wild ones or savages) were all the rage in West Berlin, artists such as Rainer Fetting, K. H. Hödicke, Helmut Middendorf, Luciano Castelli, and Salomé. Turning their backs on avant-garde movements such as conceptual art, installation art, video art, and so on, they painted pictures. These were mainly executed in a confrontational figurative style using unconstrained brushstrokes and a high-keyed, feverish palette reminiscent of German Expressionism. Their subjects ranged from urban alienation and violence to the hedonistic subculture of Berlin’s punk, nightclub, and gay scenes. Fifty years earlier, the Nazis would have pilloried their work as “degenerate” and they would have been banned from teaching and exhibiting, or worse. Their most persuasive champion was the art historian and critic Wolfgang Max Faust, whose book on contemporary German art, Hunger nach Bildern (Hunger for pictures, coauthored with Gerd de Vries), was an indispensable guide. The cover reproduced a collaborative painting by Walter Dahn and Jirí Georg Dokoupil; members of the anarchic Mühlheimer Freiheit group—named after the Cologne street where they shared studios—their paintings owed as much to the absurdism of Dada as to German Expressionism. In 1982 I bought a drawing by the Czech-born Dokoupil—who had escaped from Prague with his family after the Soviet invasion of 1968—from Paul Maenz, the first to exhibit these artists at his gallery in Cologne. Examples of this vibrant, uninhibited art adorned the walls of Faust’s apartment in Berlin, where he invited me for a drink.

The Junge Wilde and Mühlheimer Freiheit artists were well represented in Zeitgeist (Spirit of the age), a huge, eclectic show of the latest in contemporary Western painting (and some sculpture), held from October 1982 to January 1983 in Berlin’s neo-Renaissance Martin-Gropius-Bau. Curated by Norman Rosenthal and Christos Joachimides, the show was a successor to their and Nicholas Serota’s pioneering exhibition A New Spirit in Painting at London’s Royal Academy eighteen months earlier, but put more emphasis on younger artists. Originally built for the applied-arts museum of the Prussian state, the Martin-Gropius-Bau had recently been partly restored and reopened as an exhibitions venue. Scarcely a stone’s throw from the Wall, it was also in the same street that had once housed the headquarters of the SS, the Gestapo, and the Einsatzgruppen, the mobile killing squads that massacred some two million civilians, mainly Jews, in German-occupied Europe and the Soviet Union. Its upstairs galleries provided an uninterrupted view of Hermann Goering’s monolithic air ministry, one of the few Nazi buildings to survive the bombing of Berlin and still very much in use by the East German regime. (It was where it was founded in 1949.) In June 1953, during the short-lived uprising that year against the Communist government, the building had been targeted by striking workers before they were brutally suppressed by Soviet tanks. On my final visit to East Berlin, in early 1990, after the fall of the Wall but before the elections in East Germany that resulted in reunification, I was able for the first time to walk round the outside of the Reichsmarschall’s former power base—acres of monotonous unadorned classical architecture designed to intimidate—and to imagine the garden party that Goering had held there for more than 2,000 guests during the 1936 summer Olympics. Now that the Wall had been demolished and the “death strip” running alongside it ploughed up, the building was in the middle of a wasteland. I took our twelve-year-old son, feeling that he should see a segment of history before it all disappeared.

This charged location was not lost on participants in the Zeitgeist exhibition. Andy Warhol, for example, showed his Zeitgeist series (1982), in which photographic images of Prussian neoclassical architecture such as Friedrich Gilly’s 1797 design for a monument to Frederick II, and of Albert Speer’s “Cathedrals of Light” propaganda spectacles, were silk-screened onto canvas in combinations of bright synthetic colors, and multiplied. Their cool irony was in conspicuous contrast to the subjective character of much of the figurative expressionism on display. In addition to Warhol, Zeitgeist featured an impressive roster of American artists, including James Lee Byars, Robert Morris, Susan Rothenberg (the only woman in a show of forty-six artists from eight countries), David Salle, Julian Schnabel, Frank Stella, and Cy Twombly. Salle was one of eight artists commissioned to paint four large canvases, each four by three meters, for the building’s two-storied atrium. Another was the British artist Bruce McLean, then resident in West Berlin on a DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) scholarship. Since the 1960s, this program, funded by the Federal Republic, had enabled hundreds of artists, architects, writers, composers, and filmmakers from abroad to spend a year working or studying in West Berlin, helping to give the marooned city not only a raison d’être but a cosmopolitan cultural identity that it hadn’t enjoyed since the heady days of the Weimar Republic. The scheme continued in a reduced form after the end of the Cold War, its recipients including the British sculptors Rachel Whiteread (1992–93) and Mona Hatoum (2003–4).

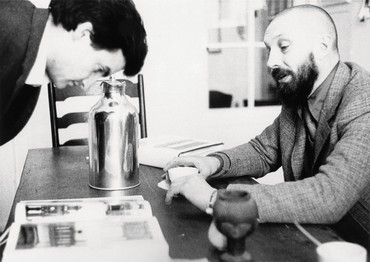

My wife [Francesca] and I stayed with McLean for the opening of Zeitgeist. He and his family occupied an enormous studio-cum-apartment in Künstlerhaus Bethanien, a nineteenth-century former hospital in Kreuzberg that the DAAD used to accommodate visiting artists. It was not unheard of for artists to stay on in West Berlin after their year came to an end. Ed Kienholz, for example, having been awarded a DAAD grant in 1972–73, lived for half of every year there until his death, at his home in Idaho in 1994. On a scouting trip for the Tate in 1981 I spent a memorable afternoon in Berlin with Kienholz and his wife, Nancy Reddin. He was in the process of finishing In the Infield was Patty Peccavi, a haunting assemblage on the subject of contraception, guilt, and the Catholic church, featuring a life-size figure of a seated naked woman. His studio was littered with objects that he had picked up in the Trödelmarkt, Berlin’s flea market, to use in future works. His Volksempfängers (People’s receiver) series, for example, incorporated old radio receivers, used as propaganda instruments during the Third Reich, that he had bought in the market along with other memorabilia of the period. He said he was fascinated by the war, which he felt had destroyed a whole generation.

Francesca joined us and that evening we all met up with the kinetic sculptor George Rickey (another former DAAD scholar) and his wife. The six of us dined in a restaurant chosen by Rickey that specialized in Franconian cuisine. Rickey was a fund of information on what to do and see in Berlin. Unlike Rickey, Kienholz spoke hardly a word of German, but his ample frame exuded bonhomie and he was clearly popular with the restaurant staff. In his cowboy boots and Stetson hat, he looked like a prosperous farmer (he told me he was a farmer’s son). The next morning Francesca and I crossed over into East Berlin to see the Schinkel bicentenary exhibition at the Altes Museum (which Schinkel designed) on the Museumsinsel. We joined a long queue snaking round the Lustgarten in the piercing March wind, but when a young couple in front of us heard us speaking English, we were ushered to the head. Afterward we walked to the Gendarmenmarkt, where I was pleased to see that Schinkel’s Schauspielhaus was at last being restored. Having each had to exchange twenty-five West German marks into East German currency at Checkpoint Charlie on our way in, we were flush with money, but there was little to spend it on. Lunch for two at the opera house on Unter den Linden, half a dozen classical-music LPs, a lavishly illustrated monograph on El Lissitzky published in the GDR, and a pair of thick woollen socks still left us with several banknotes that we knew we couldn’t change back again at the border crossing on our way out.

The DAAD had its own gallery in West Berlin, on Kurfürstenstrasse. To mark the twentieth anniversary of the founding of the “antiart” movement Fluxus, three small exhibitions were held there throughout the first months of 1983. The first was dedicated to the Korean artist Nam June Paik, a founder of Fluxus, and the American composer John Cage. The gallery’s exhibition program was directed by René Block, who published extensively on Fluxus and collected many of its artifacts. From 1964 to 1979 he had run his own gallery, the Galerie René Block, in West Berlin, making it a forum for the avant-garde. Its first exhibition included works by Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richter, and Wolf Vostell—artists who, in their different ways, did not shirk from the subject of Nazi criminality and genocide. A friend of Vostell, Nitsch staged one of his happenings with Block in 1965. Another artist to show with Block was Joseph Beuys, who performed one of his earliest actions, The Chief, in the gallery. I visited both the DAAD gallery and Block’s former gallery, which his wife, Ursula, had reopened as a record shop named Gelbe Musik (Yellow music), reminding one that the “sound” aspect of Fluxus lived on in the work of a growing number of artists. Another shop I frequented was Bücher Bogen, the recently opened art bookshop under the arches of the S-Bahn in Savignyplatz. Here one could buy the witty political posters and postcards produced by the left-wing graphic designer Klaus Staeck, whose artist collaborators included Beuys, Vostell, Polke, Hans Haacke, Dieter Roth, and others.

Beuys was of course a leading figure in Fluxus. On the last day of Zeitgeist, in January 1983, I heard him conduct a two-hour public question-and-answer session before going to visit one of the many squatters’ houses in West Berlin, much of his time now being spent in “alternative” politics. He had a spellbinding effect on his audience and could be very amusing. His environmental work Blitzschlag mit Lichtschein auf Hirsch (Lightning with stag in its glare) occupied the atrium of the Martin-Gropius-Bau in the Zeitgeist exhibition. A bronze cast of it is the only work to have remained on permanent display at Tate Modern since the museum opened, in 2000. In his use of materials associated with the Holocaust—for example, felt and fat—Beuys was the first and for a long time the only German artist to tackle the enormity of Nazi genocide, in an attempt, perhaps, to expiate it. As a volunteer in the Luftwaffe, first in Poland and later in the Crimea, he may well have heard about or even witnessed atrocities. In 1981 I had bought for the Tate a Felt Suit (1970) by Beuys for about £800 from the Nigel Greenwood Gallery in London, originally published by Block in an edition of 100. I asked Block what he knew about Beuys’s multiples; he told me that Beuys took to producing them after an unsuccessful period of trying to make prints. He had always wanted to make a suit, and Felt Suit was tailored from one of his own suits, its sleeves and legs lengthened. With its absence of buttons, it resembles a prison uniform.

Anselm Kiefer, born two months before the war in Europe ended, was briefly Beuys’s pupil. With his quotations from the poems of Paul Celan, Kiefer has made the Holocaust one of his principal subjects. Before going to Berlin, I persuaded Bowness that the Tate should acquire Kiefer’s Parsifal triptych (1973), the central canvas of which alluded to a recent period of violence and instability in German society: in the upper left are inscribed the names of members of the Baader-Meinhof terrorist gang, who had recently been arrested. In Zeitgeist I was struck by Kiefer’s To the Unknown Painter (1982), another multilayered work that acknowledged its painful surroundings. Mounted on a tomb in the center of a courtyard modeled on Hitler’s Reich Chancellery, a fragile painter’s palette appears to challenge the pretentious austerity and rigid order of Speer’s architecture. As an attribute of the artist, it also suggests his powerlessness in the face of aggressive historical forces. The painting’s distressed surface not only evokes the destruction of the Chancellery, which was a few hundred yards north of the Martin-Gropius-Bau, but symbolizes the hubris and catastrophe of the Third Reich. Since part of the Chancellery’s footprint was later used for the no-man’s-land of the “death strip,” its remains were inaccessible until 1989. Appropriately, the site is now adjacent to the 2,711 concrete stelae of Peter Eisenman’s affecting Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, inaugurated in 2005. Regrettably, my recommendation that the Tate purchase To the Unknown Painter was not taken up.

At the Neue Nationalgalerie, West Berlin’s museum of modern art, I met a man with a strong Saxon accent and an interesting history. Jürgen Schweinebraden was a print publisher and dealer who held an honorary position at the museum. He had earlier run his own small gallery in East Berlin, specializing in Western avant-garde art. Closed down by the authorities, he emigrated to West Berlin in 1980. He was a friend of the artist A. R. Penck (they were both from Dresden), whose work he had exhibited. From Schweinebraden I bought a print by Penck signed with his real name, “Ralf,” for “Ralf Winkler”—“Penck” being one of several pseudonyms he adopted to confuse East German officialdom. After years of harassment from the Stasi, East Germany’s state security service, Penck too had emigrated in 1980, or, rather, was sold for foreign currency via the notorious Häftlingsfreikauf (sale of prisoners’ freedom) system. In 1981 the Tate, on my initiative, acquired a pair of paintings by Penck from 1980, Osten (East) and Westen (West), which I had recently seen at the Galerie Michael Werner in Cologne. Werner (with Benjamin Katz) had originally opened his gallery in West Berlin, where in 1963 he gave Georg Baselitz the first of many shows. He had previously worked for Rudolf Springer, the legendary dealer in international contemporary art who had established his own gallery in Berlin as early as 1948. Now in his mid-seventies, Springer still had a gallery, where I went to see him; I was struck by his humor and charm.

It was Baselitz who told Werner about his close friend Penck, stuck in East Germany and increasingly at odds with the regime. In Osten and Westen Penck deploys his inimitable language of graphic signs and symbols to contrast his first impressions of life in the capitalist West with the less open, more rigid structures he had endured in the socialist East. I got to know Penck soon afterward when he came to live in London. In 1984 I curated his first museum show in Britain, at the Tate, for which he made a new, multipart sculpture, Memorial to an Unknown East German Soldier, reflecting sardonically on his national service in a nuclear-weapons unit of the Volksarmee.

In Zeitgeist Penck showed two enormous canvases flanking the main staircase of the Gropius-Bau. Among the older generation of Germans, he and Baselitz stood out for the raw energy of their contributions. Like Penck, Baselitz had grown up under two dictatorships, Nazi and then Communist, before emigrating to West Berlin in 1957, shortly before his twentieth birthday. By renouncing—while ironically borrowing from—the hollow figurative imagery of Socialist Realism as well as the ubiquitous tachism that he encountered in the West, Baselitz forged a new artistic language born of his interest in existentialism and outsider art. His identification with a Gothic tradition of Hässlichkeit (ugliness), at a time when his contemporaries were emulating American trends such as Abstract Expressionism and Pop art, was a conscious move to embrace rather than deny his German roots.

On a cold, snowy weekend in February I took the train from the Zoo station, through East Germany, to West Germany, in order to visit Baselitz and his wife, Elke, at Schloss Derneburg, the abandoned castle in Lower Saxony that they had bought and were restoring as their home. I had been to Derneburg the previous summer when I saw paintings in Baselitz’s studio that he would later show in Zeitgeist. On that occasion, on my advice, the Tate acquired Rebel (1965), one of the series of impotent, disheveled antihero pictures emblematic of a defeated “master race” that marked a breakthrough in Baselitz’s art. I was now following up to see if we could acquire a more recent upside-down painting—that is, a work that signified Baselitz’s engagement with the process of painting rather than its narrative content or meaning. The Tate’s purchase of Adieu (1982) was the outcome. Rising above dense woodland and half surrounded by water, its snow-capped turrets and spires glinting in the low winter sun, Derneburg seemed straight out of one of Grimms’ Fairy Tales. Another guest that weekend was Wolfgang Hahn, chief conservator at the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne and a serious collector of Fluxus, Nouveau Réalisme, and other avant-garde movements. He subsequently bought works by Baselitz.

On my way home through East Germany, the train paused at Potsdam, the last stop before the Wall and the safety of West Berlin. It was dark and snowing but the station floodlights silhouetted East German border guards with long-handled mirrors on wheels that they were sliding under the train in case anyone was clinging to the underside of the carriages in a desperate attempt to escape the GDR. Having drawn a blank, they waved us on.

In my German classes I met refugees from the Soviet bloc. It was an anxious time in Central and Eastern Europe, with the first stirrings of the popular movements that later contributed to the downfall of the Communist dictatorships and the fall of the Wall. From 1981 on, the Stasi cracked down hard on members of the unofficial peace movement who, supported by the East German churches, demonstrated against the stationing of Soviet nuclear missiles on East German soil. Some were imprisoned, others expelled. Meanwhile the official peace movement in western Europe objected to the stationing of NATO cruise missiles in West Germany but, as far as I can recall, was largely silent about the hundreds of Soviet SS20s in the GDR pointing at western cities.

All this was overshadowed, on January 30, 1983, by the fiftieth anniversary of Hitler’s appointment as chancellor and the Nazis’ “seizure of power” (Machtergreifung). For the next year throughout West Berlin, an exhaustive program of exhibitions, lectures, discussions, guided tours, publications, concert performances, and film screenings revisited this national upheaval, analyzing its causes and assessing its disastrous consequences. To give just a couple of examples, the public book burnings organized by the Deutsche Studentenschaft, the German student union, that took place in Berlin and other university towns on the night of May 10, 1933, formed the subject of a poignant exhibition at the Akademie der Künste. Even more heartbreaking was an exhibition devoted to the destruction of the city’s synagogues during Kristallnacht in November 1938. Although very few of the buildings survived, it was possible to form an idea of their size, design, and, in some cases, considerable age from plans, drawings, and photographs. A handful of religious treasures and objects connected with Jewish domestic life that had escaped despoliation were also on view. The exhibition was held in the Berlin-Museum, which, a few years earlier, had established a department of Jewish history. This eventually became the Jüdisches Museum Berlin, with its discordant, angular extension in pierced titanium zinc, designed by Daniel Libeskind and opened in 2001.

At the Goethe Institute I was fortunate in having an inspiring teacher, Reinhard Strecker, a political activist and historian who in the 1960s had publicly exposed former Nazis in the West German judiciary and civil service. Most of them had been reinstated during the chancellorship of Konrad Adenauer. I will always be grateful to Strecker for introducing me to the biting satirical songs of Wolf Biermann, the East German dissident (and close friend of Penck’s) who was stripped of his citizenship in 1976 while on tour in West Germany. I still have my copy of Biermann’s album Chausseestrasse 131, recorded secretly in his apartment in Berlin-Mitte, against a background noise of traffic from the street. Banned from recording or performing in the East, he had to smuggle in equipment from the West.

Strecker also gave me a copy of the hefty catalogue of an exhibition that had just opened at West Berlin’s Kunsthalle, 1933—Wege zur Diktatur (1933—paths to dictatorship), and urged me to visit it. The show was organized by Dieter Ruckhaberle, the Kunsthalle’s energetic director, known for sociopolitical exhibitions in which the art sometimes seemed to have slipped in as an afterthought. Reviewing the exhibition for the London Spectator, I later wrote, “With its uneasy mixture of works from the period and contemporary paintings and sculpture, [1933—Wege zur Diktatur] was no exception. . . . The temptation to draw parallels between 1933 and the present is evidently too strong to be ignored. . . . Works of art alluding to unemployment, big business and Turkish Gastarbeiter (identified, intentionally or not, as the Jews of today’s Berlin by this exhibition) were specially commissioned by Ruckhaberle.” The exhibition’s sensational aspects proved to be more controversial: the four twenty-foot-high red banners emblazoned with black swastikas hanging above the stairs to the gallery’s cafeteria, for example, or a reconstruction of Hitler’s dressing room including shop-window dummies wearing the uniforms of the SA and the SS, nooses suspended from the ceiling, and a whip pinned to the wall. Aside from these arguably gratuitous bits of theater, the exhibition had a serious didactic purpose, using documents and objects from a wide range of sources to tell its story of takeover, consolidation, and absolute control of all the key spheres in public life.

I lodged with a widow near the Olympiastadion, the stadium built by Hitler for the 1936 Olympic games. Since the end of the war it had been the headquarters of the British military administration. My landlady’s late husband, I discovered by chance, had had a “brown past”: a senior member in the press department of Goebbels’s propaganda ministry, he had written books with titles such as “World War and Propaganda” and “The English Propaganda of Lies in World War and Today” (my translations). Uninvestigated after the war, he went on to pursue a successful career as a theater director, critic, and playwright.

The public soul-searching that exercised West Berliners in 1983 would never have been possible in the eastern half of the divided city. As far as the Communist regime was concerned, there were no former Nazis in the socialist utopia of the GDR, and therefore coming to terms with the National Socialist past was not on the agenda. The idea that 17 million people were either “victims of Fascism” or heroes of the “anti-Fascist resistance” was of course another myth, but one essential to the foundation of the East German state. The truth was somewhat different: a number of top posts in the Communist regime had been held by former Nazis, who switched from brown to red totalitarianism with surprising ease. I crossed over to East Berlin on foot a few times through Checkpoint Charlie. On Unter den Linden, outside Schinkel’s neoclassical Neue Wache (new guard or guardhouse), which the GDR had designated a memorial to the “victims of Fascism,” steel-helmeted, jackbooted soldiers would periodically goose-step back and forth, apparently oblivious to any sense of irony. It really was another country.