Gerry Badger was born in Northampton, England, and is a photographer, architect, and photography critic. His books include Collecting Photography (2002), The Genius of Photography (2007), and The Pleasures of Good Photographs (2010; winner of the ICP Infinity Writer’s Award).

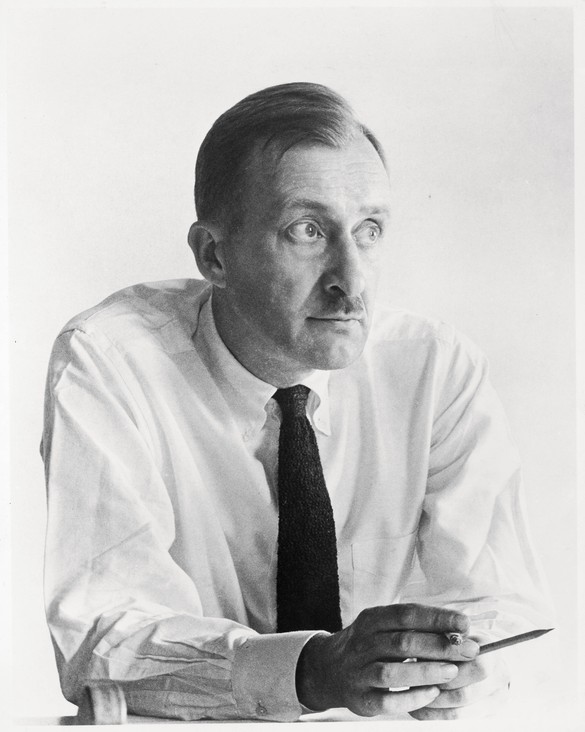

Alexey Brodovitch was a significant if now somewhat disregarded influence on the culture of American graphic design. Born in Russia in 1898, after the revolution he was exiled to Paris, where he was exposed to avant-garde art and worked as a freelance designer. In 1930 he arrived in the United States to teach design in Philadelphia, but his innovative work was noticed by Carmel Snow, editor of Harper’s Bazaar, who appointed him art director of the magazine in 1934. At Harper’s he shook up the worlds of graphic design, typography, art direction, and photography, introducing a freer, more playful European sensibility into the relatively conservative world of American graphic design.

Drawing on his exposure to Surrealism in Paris, Brodovitch applied the movement’s unconventionality to the magazine’s pages. He contrasted groups of small images with larger ones, printed photographs showing torn edges, found creative uses for the white space around image and text, and deployed contemporary fonts. Everything was done to stimulate readers and agreeably jolt their expectations. As Brodovitch said, “The public is being spoiled by good-technical-quality photographs . . . and they have become bored.”

As well as hiring out-of-left-field figures (in fashion photographers’ eyes) such as Robert Frank, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Man Ray, and Lisette Model, Brodovitch nurtured the careers of fashion greats Irving Penn and Richard Avedon. His Design Laboratory classes, begun when he was still in Philadelphia and continued in New York, brought together an eclectic mélange of photographers, established and not, to argue about and push the medium’s boundaries—photographers including Avedon, Diane Arbus, Bruce Davidson, Art Kane, and Garry Winogrand. The eclecticism of these meetings and their long-term impact, lasting decades, may be his most enduring legacy. As Penn once put it, “All designers, all photographers, all art directors, whether they know it or not, are students of Alexey Brodovitch.”

If Brodovitch’s great legacy lies in his own design practice and in his teaching—in other words, in facilitating the work of others—he also made a direct contribution with artwork of his own. Between 1935 and 1939, he photographed the rehearsals and performances of ballet companies visiting New York, including the Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo, which he’d known in Paris when it was Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Devising a radical method, he used a hand-held 35mm camera in dim interior light, necessitating exposures as slow as 1/5th of a second that produced blurred, grainy, contrasty images. The strategy was typical of his restless, exploratory nature—his whole creative persona was about pushing boundaries and breaking rules.

Ballet, published by the New York publisher J. J. Augustin in 1945, contains 104 images and is divided into eleven “chapters,” each describing one ballet. The book’s layout and design are as radical as Brodovitch’s photographs: because each image is bled across a single horizontal page, each section becomes a continuous photographic strip, with double-page spreads made to look like a single panoramic image and the whole section configured like a strip of movie film. The wide horizontal format, somewhat unusual, symbolizes the ballet audience’s view of the stage, giving the book a vibrancy and a fluidity that perfectly capture the movement of the dance. Indeed, Ballet is a consummate example of the suggestion of motion in photography, and one of the most dynamic and cinematic of all photo books. It is also a forerunner of the “stream of consciousness” feeling of the postwar existential movement in the arts, showing almost-documentary photography meeting Abstract Expressionism.

Now, two forthcoming events allow us to reevaluate this important but somewhat neglected figure by today’s photographic generation. First, the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia is presenting an exhibition in the spring, curated by Katy Wan of Tate Modern and entitled Alexey Brodovitch: Astonish Me. The exhibition concentrates on Brodovitch’s legacy and examines his collaborations with many major twentieth-century photographers. It will prove a most welcome addition to our knowledge and understanding of Brodovitch.

Second, Little Steidl of Göttingen, Germany, is about to publish a new edition of Ballet. Photo-book enthusiasts will surely welcome the publication since Ballet is one of the rarest of photo books, more often talked about than seen: it was printed in a very small edition, and even here Brodovitch’s penchant for rule-breaking is evident in that he challenged accepted practices in the very making of the book. Careful research by Nina Holland and Joshua Chuang found unexpected anomalies in the printing, the typography, even the page trimming, indeed almost everywhere they looked. Given Brodovitch’s vast experience, Little Steidl concluded that these departures may have been deliberate, and that the book’s flaws only served to make it more perfect. Ballet—the only book its author made of his own work over a revolutionary and prodigious four-decade career—may prove as elusive as was Brodovitch himself.

Alexey Brodovitch: Astonish Me, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, March 3–May 19, 2024