Amit Chaudhuri is the author of eight novels, the latest of which is Sojourn (2022). He is also a poet, essayist, short-story writer, and musician. His New and Selected Poems is scheduled to be published in 2023 in the NYRB Poets series. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and edits literaryactivism.com.

Satyajit Ray’s grandfather Upendrakishore was a writer (notably of children’s stories, like Abanindranath Tagore), an artist and illustrator, an amateur musician, the founder of the children’s magazine Sandesh, and a pioneer in block-print technology. Ray’s father, Sukumar Ray (who died when Satyajit was two), studied photo engraving and lithography in London and was the author and illustrator of an extraordinary corpus of nonsense verse and other writings. These artists share a backdrop of certain philosophical traditions (the Tagore family was specifically interested in the Upanishads and the idea expressed in those texts of ananda, bliss, or, in India’s rasa aesthetics, the taste of bliss), Indian classical, court and folk art, Chinese art, and Japanese woodcuts, and this context makes possible constant forays into children’s genres and artistic styles inappropriate to “proper”—that is, neoclassical, realist, and academic—painting. In three generations of Rays—Upendrakishore, Sukumar, and Satyajit—it induces a commitment to the stewardship of Sandesh, but also, as the name indicates (sandesh means both “message” or “news” and a sweet made of milk curd), to the idea of blissful tasting. Sukumar Ray had a club for nonsense-related creative activity, socially relevant discussion, and periodic feasting that he called both the Monday Club and the Manda Club, manda being a Bengali word for “sweetmeat,” continuing the theme of savoring. It is in these contexts—rather than in art house or neorealist cinema alone, or in what Salman Rushdie has admiringly termed Satyajit’s “lyrical realism”—that we must place scenes in many of Ray’s films.

Ray started out as both an artist and an aficionado of film. In 1940, when he was eighteen, his family sent him off to study at Visva Bharati, the university founded by Rabindranath Tagore in Santiniketan. There he studied art under, among others, Nandalal Bose (another experimenter with Japanese pictorial innovations). Ray’s apprentice work from that period includes paintings in the Japanese style, where the Bengali letters of his signature appear in the hieroglyphic manner introduced by Okakura Kakuzo and Abanindranath Tagore. Ray, in some ways, chose the artist Benode Behari Mukherjee as his mentor. For Mukherjee, the Buddhist frescoes in the caves of Ajanta (many of them deliberately left unfinished), dating from as far back as the second century BC, had been revelatory; they taught him that painting should be provisional, and achieved on rudimentary surfaces, like the walls of the unlit caves. So Mukherjee painted on available surfaces himself: the walls and ceilings in Santiniketan’s art school, Kala Bhavan. Here, again, the frame and the idea of gallery space, which give distance and control to the viewer, are done away with; the viewers are brought in, they cannot stand outside. Afternoons spent gazing on walls at home in Kolkata had already prepared Ray for the thought that art—and, later, cinema—was not so much a window onto reality as a surface constituting its own reality: when rays of light entered through the shutters of the wooden windows, “like magic, the traffic in the street outside could be seen inside the closed room; and one could make out clearly cars, rickshaws, cycles, pedestrians and other things. I do not know how many years I spent lying and watching this free Bioscope.” The analogy with the Bioscope, a film camera, comes from a filmmaker’s retrospective knowledge, but this memory also comes from one who had studied art, engraving, and woodcut-making with Mukherjee and Bose in Santiniketan. In the 1950s, Mukherjee began to go blind, but continued making art well into his blindness. This moved and engrossed Ray, and he later made a documentary, The Inner Eye (1972), on his former teacher’s journey from sight to sightlessness. Ray was concerned with the constraints of seeing, and was speculating on ways in which the artwork might become free of the artist. As Roland Barthes, quoting Guy de Maupassant, had said, “The only place in Paris where [you] don’t have to see [the Eiffel Tower]” is when you’re in it.

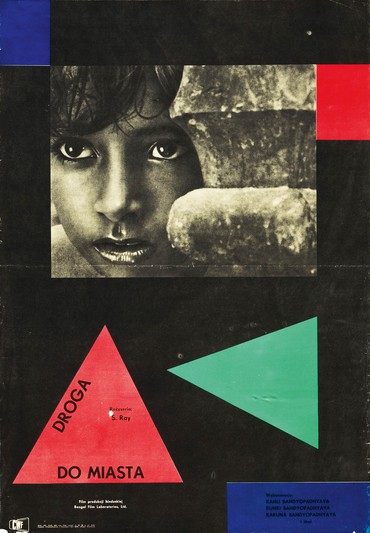

Ray encountered Pather Panchali, Bibhutibhushan Bandhopadhyay’s 1928 novel about Apu and his family in the fictional Bengali village of Nischindipur, in 1945, when he was commissioned, at the age of twenty-three, to make woodcut-style images to illustrate a version of the book that had been abridged for children. Ray first read Bandhopadhyay’s novel in this version, in his capacity as illustrator; at this point he was not even a filmmaker manqué. The idea for making the film probably came to him in 1950. What had happened between Santiniketan (where he didn’t complete his course) and this moment? In 1943 he had become a commercial artist in an advertising company, and before long was a force in the appreciation of cinema, helping to create a film society, India’s second, in 1947. He had spent time with Jean Renoir (whom he admired) when the French filmmaker came to Bengal to make The River (1951); his encounter with Vittorio De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette (The Bicycle Thief) (1948) and Italian neorealism had revealed to him that improvising within limited means was a bonus to a filmmaker; he was a devotee of John Ford’s westerns; and he was an illustrator. That fact and its relation to the aesthetic of Bengali children’s literature, of opting for play and economy in artmaking, are part of the mix that brings Ray’s version of Pather Panchali and his oeuvre into being. Paying tribute to Ford in 1973, he gently interrogates whether Ford ever thought “of himself as an artist” (Ford “said filming for him was a job which he enjoyed for its own sake”) and emphasizes, as one would with a craftsman or, in light of Hokusai, a woodblock printmaker, his apprenticeship to a motif: “Like [Pablo] Picasso’s obsession with the bull, [Paul] Cézanne’s with the apple, Bach’s with the fugue, and the Hindu miniaturists’ with the theme of Krishna, John Ford had a lifelong affair with the western.” None of the figures to whom Ray compares Ford belong to the Renaissance; they’re all situated in complex histories or moments that are at an angle to that Renaissance legacy of “great art.”

Here we must place Ray (and the personnel who contribute to his visual language: the cinematographers Subrata Mitra and Soumendu Roy; the art director Bansi Chandragupta): at an angle to the “great art” lineage that privileges the viewer’s vantage point outside the artwork. Two separate series of shots in the first half hour of Pather Panchali “transgress . . . this separation . . . of seeing and being seen” (Barthes again, on the Eiffel Tower—clearly thinking of Hokusai’s Mount Fuji). Right at the start, Apu’s older sister, Durga, still a child, is hiding, for no ostensible reason, behind a kochu (arum) leaf to spy on her mother passing by. Not so much perspective as layers characterize the scene: the path, the large leaf, the face. In the next shot we see the back of Durga’s head, then the leaf, then the woman. Once home, Durga first takes the lid (a handheld fan) off a pot to take out bananas, replaces the lid, peers into another vessel to scoop out a bowl of milk, then bends down to inspect something inside a large disused clay pot. Now, from inside this pot, we look up at Durga’s face, hovering above and smiling. Next moment we’re outside the pot, looking at her while she retrieves kittens from its depths to give them milk. This is the first series of shots repositioning the viewer.

Afternoons spent gazing on walls at home in Kolkata had already prepared Ray for the thought that art—and, later, cinema—was not so much a window onto reality as a surface constituting its own reality.

In the next fifteen minutes a few years pass. Durga becomes a teenager. Apu is now a boy; he’s about to make his entrance. She goes into a room and stirs her brother, who’s pretending to be asleep. She keeps lifting a tiny bit of the covering he’s lying under, as if exploring a tear, and then prises open his eye with both thumbs so that we suddenly glimpse pupil and eyeball. Now Apu rises, exuberant, like a great wave. This is the second series of repositioning shots. Collapsing distance, they refer us back to Hokusai’s way of noticing, and being noticed by, Mount Fuji. You conceal or hide yourself not by being at a distance from the work but precisely by entering what Barthes calls its “blind point.” This “blind point,” with which both Hokusai and Ray replace the vantage point, can be anything: the inside of a pot; the eye, hidden but wakeful under the eyelid.

Given his precursors in the visual arts—Mukherjee, the muralist; Bose, who left his imprint on the world of Bengali children through his lino-cuts for Rabindranath Tagore’s primer Sahaj Path (Easy learning, 1930); his writer/printer/illustrator grandfather and writer/illustrator father; and also Gaganendranath Tagore, Claude Monet, Henri Matisse, the Belgian comic book artist Hergé, and, of course, Hokusai—Ray is interested not in heavy strokes, deep backgrounds, and vanishing points but in cursive flows, transverse lines. This preference is evident in the opening credits of Pather Panchali: Bengali longhand on writing paper. The film’s most renowned scene—in which the children run toward train tracks through a field of kaash blossoms to marvel at a passing train—begins with Apu and Durga puzzling over the telegraph wires near the tracks. The wires are humming strangely, but their crisscross is absorbing to Ray because the lines form a grid or block: not itself a picture, but the basis of one. The kaash—stalks and feathery blossoms—bend right as the children, curious but also indifferent, move forward, stop, move forward. The white of black-and-white films is generally the bits that are lit, empty, or reflecting the light; the white smudges of the kaash are an extra print-white. Although the children are running forward, they also stray desultorily right or left. Hollywood movies and Renaissance paintings tell us that waves move toward us; Hokusai sees them moving across. This inflects how the train appears. In Ray’s woodcuts for the children’s book, he imagines this in conventional cinematic terms, the train moving frontally toward the reader, very much as it does in L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (The arrival of a train at La Ciotat station), the Lumière brothers’ foundational bit of filming from 1896. It’s in his film that Ray taps into the delicate woodblock possibilities of the image. First you see the black smoke—a horizontal black line going right, more black than the shadow that forms the black of black-and-white. The train beneath it is a dark strip going left. Then the train is studied close up, as swift blotches, and, just as it vanishes, the children rise up, reaching the tracks from the opposite side; we are no longer following them—we face Apu as he arrives. We are Mount Fuji, or have gone inside the Eiffel Tower.

Ray is not a “painterly” filmmaker. When we use that word, we think, even without being aware of it, of a Renaissance painting. Ray is working with possibilities of design, angle, and line created by the woodblock, fonts, and print. He doesn’t distinguish between poster or book cover (he designed the jackets of the books he wrote for children) and “actual story.” Cover art and content are interchangeable for him. The short film Samapti (Ending, 1961) is based on a short story by Rabindranath Tagore about a tomboy, Mrinmoyee (her pet name is Pagli or “madcap”), who finds herself, to her chagrin, married to a young Kolkata bhadralok (the Bengali word for the bourgeois, meaning, literally, “polite person”), Amulya. The film begins with a close-up of the sails, covered in patterns, of a boat approaching a riverbank. The expanse of the sails merges into the expanse of the bank, their worlds continuous with each other.

Ray, as filmmaker/woodblock artist, is drawn to river and riverbank. The flatness and faint horizontal lines, the near-indistinguishability of bank and river, mesmerize him. They have a lightness that he wants to situate at the interface of woodblock and film. Not for him, then, Canaletto’s canals, organized by, and proceeding toward, a vanishing point; the lateral line interests Ray. You see this in the first scene of Samapti. The riverbank is a place of arrival, transition, and congregation across a surface characterized by intermittent detail: the abandoned front of a boat in which Mrinmoyee stores things; a large tree to sit under; a swing that Mrinmoyee occupies at moments of abandon and anxiety. Ray’s woodblock-printer instincts are at their most attuned in Samapti. He repeatedly revisits the riverbank motif. The human figure occasionally takes center stage in the frame, but we’re more often presented with layers. Many of the most effective backgrounds have Mrinmoyee in them, glimpsed through a window, trying to climb a tree, falling back, momentarily disrupting the foreground. There’s a simultaneity of motion in front and back layers that you see in Hokusai. Ray introduces Barthes/Maupassant’s “blind spot,” the entering of the Eiffel Tower, soon after we see Mrinmoyee watching at a window while Amulya, inside, is introduced to a prospective girl-bride who’s singing a song with a harmonium. The squirrel Mrinmoyee is holding darts into the room and she goes chasing after it, throwing the occasion into disarray; the squirrel (no longer visible) plunges into the clutter under a bed, and from beneath the bed we see Mrinmoyee bending low, straining to recover it. The below-the-bed clutter constitutes Samapti’s Mount Fuji location.

Ray had discovered the lateral possibilities of the riverbank in Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1956), the second film in the Apu trilogy, where, following Apu’s family, he shifted location to Banaras. The horizontal lines of the ghats presented his woodblock-artist instincts with an opportunity. It’s in the trilogy’s final installment, though—Apur Sansar (The World of Apu, 1959)—that he makes his first sustained attempt at the woodblock sublime. One third of our way into the film, we find Apu accompanying a friend to his ancestral village for the friend’s cousin’s wedding. While wedding preparations are underway in the family house and the young bride is being adorned, Apu is daydreaming—reading, playing a flute—on the upper reaches of the bank of the river by which they had arrived earlier. The wedding procession, straggly but long, is advancing on the lower bank, a line of men in white dhotis and a palanquin (with the groom inside) moving left to right. Apu is no more aware of them than he’s aware of the fact that he’ll have to marry the bride—the groom will turn out to have a mental disorder; Apu’s friend will plead with him to become the groom. The woodblock sublime, then, contains a prescience of the unknown, just as Hokusai’s prints are about chance, hinted at by the movement of light, wind, and water, so that even Mount Fuji lacks fixity. The long line of men with the palanquin gradually outpaces a boat being rowed with giant but futile strokes by a boatman. Apu begins to doze; he lies down. All lines move sideways, seemingly reposeful but actually animated. The scene reworks Hokusai. It reminds us that lines that go, and things that bend, one way or another are bending toward the unknown. Such an image is not meant to be studied for its verisimilitude.

What Matisse does with a carpet or rug Ray does with the verandah. What Matisse does with the carpet’s patterns Ray does with shadow. The source for both is the block print.

Ray’s contributions to a lineage that includes Monet and Matisse, and of which he is the last great artist, are too numerous to go into here. I’ll mention only a few luminous instances post-Samapti. In Charulata (1964), the protagonist Amal’s arrival at the scene of the subsequent action—a North Kolkata mansion—coincides with a monsoon storm. A sideways-moving wind and rain spray briefly envelop the verandah. Women run in the haze, collecting things—clothes, a bird in a cage. Papers (it’s a newspaperman’s house) fly about. The chaos of the scene—its fine, unruly lines—is embedded in the tale as a tribute to the woodcuts that engaged Upendrakishore. The gust of wind that troubles the travelers in Hokusai’s Ejiri in Suruga Province (c. 1830–32) unsettles a North Kolkata house.

It was while watching and rediscovering Ray’s work outside his so-called art house oeuvre—films based on Bengali detective stories, or about his own fictional detective, Feluda (da is an affectionate Bengali suffix meaning “older brother”)—that I began noticing these woodblock proclivities. In the first of his Feluda films, Sonar Kella (The Golden Fortress, 1974), Feluda and his team, the teenager Topshe and the detective novelist Jatayu, arrive in Rajasthan to rescue the child Mukul from kidnappers. They check into the Jodhpur Circuit House. Ray spends a few moments with the long verandah adjoining the rooms, crossed with horizontal lines of shadow in the late-morning winter sun. What Matisse does with a carpet or rug Ray does with the verandah. What Matisse does with the carpet’s patterns Ray does with shadow. The source for both is the block print.

Ray’s last great work—his final statement—in this aesthetic is Joi Baba Felunath (The elephant god, 1979). We’re back in Banaras, this time with Feluda, who’s there to investigate a robbery and murder. Certain scenes in the film are energized by Ray’s desire to be a different kind of artist; this yearning for transformation, to escape one form, genre, or self into another, is important, as it’s what introduces disruptive tonalities to the genre the artist has chosen to work with. Arriving in a house from which a golden figurine of the elephant god Ganesha has gone missing, Feluda, Topshe, and Jatayu are transfixed by the ancient opulence of the building. At one point Feluda picks something up from a table: an old-fashioned animation book, whose characters race through the story if you flick through the pages. This booklet is related to the child in the house, Ruku, but it also hints at Ray’s excitement about his own hybrid artistic lineage.

At least two sites—Ruku’s room on the roof (or, as Ruku calls it, “Captain Spark’s room”) and Banaras’s ghats and alleys—are key to the mystery’s unraveling. They also contain multiple references to the film’s creative provenances. Topshe, Feluda, and Jatayu always move across Ruku’s room, and, in another transverse movement, encounter his reading spread out on the bed. These are mostly comic books: three Phantom comics, one half-concealed Tarzan, and Hergé’s Black Island (1937–38; Ray loved Tintin comics for their visual liveliness, and Hergé, it should be added, pays homage to Hokusai in his drawing of a wave about to submerge Tintin’s boat in The Blue Lotus of 1936). There is also Ruku’s own colored-pencil drawing of the Phantom and a stamp album with London Bridge on the cover. Topshe also holds up a Bengali book about Captain Spark; more sketches by Ruku of the Phantom and other characters are stuck to the wall. As with the sails with stitched motifs at the start of Samapti, Ray refuses to separate one image (of Topshe, Jatayu, and Feluda in the room) from another (the jacket of The Black Island). Film is becoming drawing is becoming woodcut and vice versa, while it’s sharing with us the transition from material to artifact and artifact to material. The books are splayed out; the vision has to flow over and past them. In the room, the camera sometimes descends to the level of Ruku’s head, while Jatayu and, behind him, Feluda, and, suddenly, Topshe on the left create layers of presence, not unlike Durga hiding behind the kochu leaf in Pather Panchali. Human bodies (Topshe, Jatayu, Feluda), by making configurations inside the room while standing larger than life before Ruku, destroy Renaissance-type proportions to do with foreground and background.

The other sequence I have in mind is yet another echo of the pot in which Durga kept her kittens, or the underneath of the bed to which Mrinmoyee’s squirrel escaped: “It’s the only place in Paris where I don’t have to see it.“ The sequence begins with pure lateral movement: Feluda is shadowing a suspicious character who’s just gone from the ghats up some steps into an alley. Usually, chases and stalking scenes follow the pursuer or the pursued; Ray’s camera, for a long time, moves sideways as Feluda walks across the upper ghats to reach the steps to the alley. His background is giant Hindi lettering advertising the Banarasi Rink Milk House, then more Hindi—political graffiti about poverty and hunger. “Background” isn’t the right word: again, Ray is fashioning an interchangeability between the human figure and lettering. All are of equal interest. The incredible potential of the flat, sideways shots (rather than close-ups, perspectives, or panoramas) that Ray has explored throughout his work comes to fruition in these eleven seconds. Then Feluda climbs up the steps into the alley and, following the man, enters an immense, beautiful haveli (a North Indian mansion). The man disappears. Feluda explores the mysterious spaces of the haveli, finds a gun and false hair among the man’s possessions, and, when he hears him returning, hides behind decrepit, abandoned furniture, something like a broken bit of a rattan bed. Through an untidy rent in the rattan, Feluda spies on the man up close. This again—like Durga’s pot and the clutter under the bed in Samapti—is a Mount Fuji moment, and one of Ray’s most eloquent observations that (in contrast to the assumptions underlying the Renaissance painting) we can’t be external to language or idiom; we must disappear into it.

The film that Ray devotes wholly to this matter of doing away with “standing outside” may be his shrewdest and most delicate work: the 1962 color film Kanchenjungha. The eponymous peak overlooks Darjeeling, where holidaying Bengali bourgeois families, bygone aristocrats, and a petit bourgeois schoolteacher have all gathered and are wandering about, running into, or breaking away from each other in real time over 1 ½ hours. Part of Ray’s framework comes from Renoir’s La Règle du jeu (The Rules of the Game, 1939): the possibility of estrangement, comedy, and class observation arising from the bourgeois’ transposition from their natural habitat to a place that combines natural beauty with the weight of history—in Renoir’s film, a country manor and its grounds; in Ray’s, Darjeeling, a hill town once favored by the British as an escape from the summers at lower altitudes. The other prompting for Ray, besides Renoir, is Mount Fuji. While reviewing their lives, the visitors are hoping to catch a glimpse of Kanchenjunga, which is reputed for capriciousness and staying hidden behind mist and cloud. Spotting Kanchenjunga, or being disappointed by its nonappearance, is evidently as much a bhadralok ritual as any of the other ones shown here are: wearing a sari, riding a pony, discussing the failure of one’s marriage. Of course, it’s difficult to see Mount Fuji in Hokusai; the cone is often a wave or an outline. It will not be spectacle, nor will it be sole observer. Toward the end of the film, the atmosphere clears; the golden peaks become visible. The aristocratic patriarch who has briefly lost his way doesn’t notice. Made two years before Barthes wrote his Eiffel Tower essay, Kanchenjungha stands with it as a remarkable meditation on the way in which art draws the viewer in without their necessarily knowing it.

Read Part I: “Mount Fuji in Cinema: Satyajit Ray’s Woodblock Art”