Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at the Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames and Hudson in May 2021.

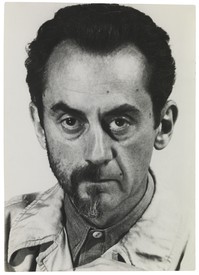

Margit Rowell, after working many years (1969–2001) as a curator at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, at the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, in Paris, and at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, now lives and works as an independent art historian in Paris. Photo: Daniel Soutif

Richard CalvocoressiLee Miller and your mother, Tanja Ramm, knew each other in New York; they later shared a flat in Paris and both modeled for [Jean] Patou and Man Ray.

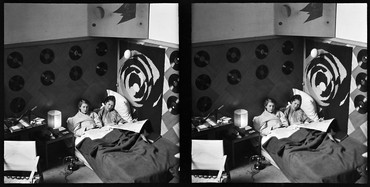

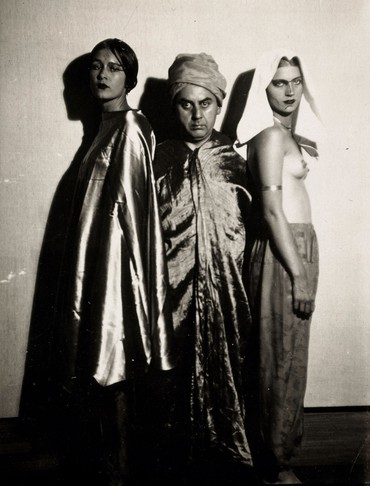

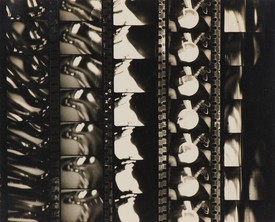

Margit RowellYes! Let me show you something. This is a photo by Man Ray of Lee and my mother.

RCThat’s fantastic.

MRMy mother was Norwegian-American, but she had dark eyes and hair, unusually enough for a Scandinavian. So I think that Man Ray liked this photograph because it was like a positive/negative situation.

RCOh, that’s so nice, to have that. They met, I think you’ve said, in New York in the mid- to late 1920s at art college?

MRThey met, it seems, in 1926, 1927, at the Art Students League. The Art Students League is a place where people like David Smith and many eminent artists started their careers. But according to my mother, she and Lee didn’t become close friends then. They were just in the same class. And then they met again in 1929 at a cocktail party at Condé Nast’s and realized they had a lot in common. They left for Paris together in 1929.

My mother came from a relatively modest family, and her stepmother told her to lie about her age and go into modeling to bring home money for the family, as it were. So my mother started modeling quite young. I went through the archives at French Vogue at one point when I was doing some research on this subject, and I realized that these were the first years when professional photographers’ models existed. Before that, you had aristocrats wearing the clothes in Vogue. Then you had a period when there were drawings of fashion. Lee and my mother were among the first generation of professional models.

RCThat’s very interesting.

MRThey were both photographed by [Edward] Steichen in New York, as well as by Arnold Genthe and I think [Horst P.] Horst. And once they got to Paris they were photographed by [George] Hoyningen-Huene, who was the art director of Vogue in Paris.

When they first arrived in Europe they went to Italy together, and then they split up and met again in September. They were there together until 1931, when my mother married my father. Lee was her witness at the wedding.

RCAnd that was in Paris, was it?

MRThat was in Paris in February 1931, yes. And then my parents left and came back to the United States.

RCSo your mother didn’t have an ambition to become a photographer like Lee—

MRNo, not at all. My mother wanted to be a painter, actually. Once Steichen came to her studio and she asked him for advice about her painting, but he didn’t find it interesting and that was that.

RCIt was Steichen, I think, who recommended that Lee make contact with Man Ray in Paris.

MRYes. You know, it’s always said that Lee learned everything from Man Ray. But my theory is she knew a great deal because of her father [Theodore Miller]. Her father was this so-called amateur photographer, but I don’t think he was that amateur. He took excellent pictures. She grew up with him taking photographs of her and everybody else; I think she knew a lot about photography before she came to Paris.

RCAbout the technical side as well, because her father was kind of an inventor, an engineer, wasn’t he, by trade?

MRExactly. So they came to Paris, and Lee told Man Ray that she wanted to become his assistant and Man Ray said he didn’t take assistants. Then at one point my mother had to go back to the United States, which you can imagine—I mean, there were only boats in those days—it was a seven-day journey. And she said that when she came back, Lee and Man were lovers. Man told Lee he was going to the South of France, and she said, “I’m coming with you,” and the rest is history.

There are photographs of Lee and Tanja in the studio in Montparnasse. Apparently, Man Ray decorated the studio. The studio had one wall covered with phonograph records. It also had an ostrich egg hanging from the ceiling!

RCWas that where they lived?

MRThey first lived at a hotel, and then that’s where they lived, yes. It’s a beautiful building, built in 1927, which means that it was very avant-garde to move into this brand-new building.

RCIs it by [Robert] Mallet-Stevens or an architect like that? I remember going—last year or the year before, they put up a plaque to Lee there, on rue Victor-Considerant.

MRYes, it’s on the corner of Schoelcher and Victor-Considerant. It’s in the style of Mallet-Stevens, but he was not the architect. The architects were Gauthier, Père et Fils, otherwise quite unknown. It’s a duplex; Lee occupied the ground floor, and then there was a mezzanine and my mother slept upstairs. Because by this time my mother knew she wasn’t going to stay in Paris; she met my father at about that time. Lee said, “Don’t get a flat, come and live with me.” Lee also did her photographic work in that apartment.

The building became famous because Simone de Beauvoir also lived there starting in the 1950s.

RCIn fact, there are two plaques on that building now, one to Lee, which was put up last year, and another to Simone de Beauvoir around the corner, I think.

MRI lived with a sort of vague mythology of this time—I grew up in Baltimore, and in our attic were all these photographs with curled edges just hanging around. I would ask about them, and my mother would say, “Oh, this photographer I knew in Paris named Man Ray took these photographs.” It was not considered important. But I thought they were amazing. Then when I became an art historian, I understood the significance of Man Ray.

I should also say that when my mother came back to the United States with my father they lived in New Haven, where my father was a classics professor and archeologist. He was much more interested in deciphering inscriptions than he was in art objects. So when people say to me, Oh, your art history interest comes from him—it doesn’t totally.

Anyway, Lee came back from Paris in 1932 to open her studio in New York. Tanja would go down to the city and Lee would photograph her. She would do photographs for advertising with my mother dressed, for example, in bridal gowns. She also did beautiful portrait photographs of her. So they kept up at that time back in New York.

In fact, there’s another funny story, which is that, before her marriage, my mother dated the Egyptian man who Lee eventually married—

RCAziz [Eloui Bey], yes.

MRMother dated him at one point, and Lee said to her, I don’t know what you see in that man; he’s so boring. And then, my mother said to me, “The next thing I knew, she married him.”

RC[Laughs.] That’s a very good story. Did your mother go on modeling after she married your father, or did she more or less give that up?

MRShe did, because they didn’t have a lot of money—well, and she was bored. She had been told she couldn’t have children, and she was sitting around being unhappy, so she went to New York during the week and modeled. She modeled for Anton Bruehl, who was one of the first fashion photographers to work in color. Since Condé Nast had all the equipment and technology, Bruehl did lots of color photographs for him. There’s a famous photograph called Body by Fisher, and it’s about automobiles, the automobile body, built in Detroit, but it has this woman with a beautiful human body as the advertisement. That’s my mother, Tanja.

RCFantastic.

MRThat was like 1932, 1933. She did continue to be a photographer’s model. And she and Lee did continue to have this connection up through when Lee married Aziz—

RCAnd went to Cairo. That was probably, I think, something like 1934 or 1935. I mean, she had that studio in New York for a few years and did photograph quite a lot of people from the theater, the stage. She photographed the cast from Four Saints in Three Acts, the Virgil Thomson opera.

MRLee was very successful, and there was even a waiting line for her portraits.

She and my mother lost contact after that period. Then in 1967, there was an homage to Man Ray at the American Center in Paris, which was on the boulevard Raspail, right around the corner from where I lived. I went and introduced myself to Man Ray, and I said, “You photographed my mother, but I’m sure you wouldn’t remember her because you must have photographed hundreds of people.” He asked her name, and I said, “Tanja Ramm.” And he said, “Oh my God, of course I remember her. Of course I remember her.” He grabs Roland Penrose, who was there, and he says, “And this is Lee’s husband.” I had no idea. As an art historian, I had read Roland Penrose. I had read him on Miró; I had read him on Picasso.

RCYou had no idea that he had married Lee?

MRI had no idea he’d married Lee, no. No idea. I spoke to Roland, and Roland said, “Well, Lee would be thrilled because she and Tanja haven’t been in touch in so long.” So he gave me their address and I sent it to Tanja, and Tanja got in touch with Lee. My parents went to London and they had this reunion. My parents’ fortieth wedding anniversary was in 1971 and Lee came to Baltimore specially from London, which I thought was so wonderful. That’s when I actually met her for the first time. She was delightful. By 1971 I was working in New York at the Guggenheim, and in 1972 I did a Miró exhibition. Roland and Lee came and I invited them to dinner. I cooked for three days. I was so nervous because she had become this gastronomic chef.

RCOf course, that was her sort of late career, wasn’t it?

MRI guess, although was it a career, or just an occupation? I invited them with [curator, museum director, and writer] James Johnson Sweeney and his wife, who were from the same generation and had the same relationship to Miró. And everybody got very drunk and it was a wonderful evening. After that, Lee and Roland had a habit of coming quite often to New York, and Lee would come to dinner by herself when Roland was doing other things. So I saw something of her. She was wearing a white turban, I remember, the last time I saw her (because of her cancer); I thought she was one of the most beautiful women of the twentieth century, really. She was smart and funny and not pretentious at all. She was really an amazing person who I had a wonderful, small relationship to.

I lived with a sort of vague mythology of this time . . . in our attic were all these photographs with curled edges just hanging around.

Margit Rowell

RCThat’s lovely. At that time, the late 1960s, early 1970s, were you aware of her achievements as a photographer, or did that come later?

MRI’d say not really. I think that came later.

RCIt seems that really it wasn’t until after her death that her reputation began. Her son Tony [Penrose] has said that he really got to know his mother after she died by discovering all these negatives and prints in the attic. It’s an extraordinary story, that she must have suppressed her previous life and just got on with, as you say, cooking, and there were other passions, like music, I think.

MRYes, and having lots of people over—they were extremely sociable. You know, her archives were kept at Vogue. The story I think I heard from Tony is that British Vogue called him one day and said, “We’re moving, we have all these boxes of negatives of your mother’s work, are you interested?” They sent him the archives, and that’s when he discovered her body of work.

RCI hadn’t realized that.

MRIt’s interesting that she never did anything with them later on.

RCI suppose at that date, we’re talking about the 1950s, 1960s, first of all, there weren’t many photography galleries putting on exhibitions of photographers’ work. As you say, most of what she did was for Vogue. The whole discipline of photography as an art form didn’t get serious critical attention until, I suppose, the 1960s, 1970s, and that was really in the last ten, fifteen years of her life. I think now it would be very different.

There’s been a lot of recent emphasis on Lee’s work as a war photographer, a combat photographer in World War II, and the amazing dispatches she sent from the front, which were published in Vogue alongside the photographs. And that’s obviously of great relevance today, in view of what’s happening now around the world.

MRDo you know there’s going to be a film on her as a war photographer?

RCThat’s right, starring Kate Winslet.

MRWith Kate Winslet, yes. But it’s theoretically only that period.

RCI wonder whether, you know, her work as a fashion photographer and a portrait photographer has been given the attention that it should. I think her portraits of artists and writers are some of the most powerful and memorable things she ever did. And in fact, I think after the traumatic experiences that she had in the war, she kind of buried herself in photographing friends: artists, writers, intellectuals, those who came to stay with them at their farmhouse in Sussex, and also on her travels to the United States and elsewhere. The war photography is obviously very, very important as witness to destruction and atrocity and so on. But in my view what will survive are her portraits of artists whom she knew intimately. Because she was an artist herself and she was married to one, and was obviously great friends with Picasso and so many others, I think she had a kind of understanding and insight into them.

MRI think she considered the wartime work as reportage. And furthermore, the photographs belonged to Vogue, they didn’t belong to her, so they were not very present in her day-to-day landscape. It was something that was behind her. I have to be honest and say that I didn’t really know her portrait photography after the war that well.

Your exhibition at Gagosian emphasizes the portrait works, is that correct? From the period in 1932 when she had the studio in New York?

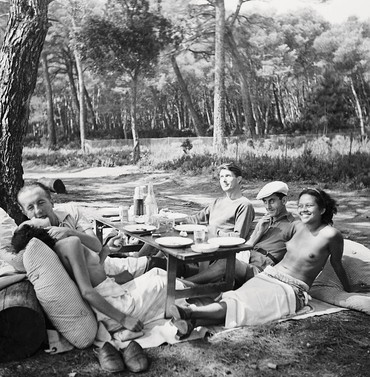

RCYes, a few from that era. And also from that summer they all spent down in the South of France in 1937, with those picnics on the beach and so on. Then after the war she took a huge number of photographs of Picasso in his studios, some of which were used as illustrations in Roland’s 1958 biography of Picasso. They were forever going over to the South of France to stay with Picasso and she would photograph him. And then he came once to Farley Farm, memorably, when Tony bit him. [Laughs.] Tony later did this book called The Boy Who Bit Picasso [2011]. I think that visit was in the early 1950s or something like that. I suppose she took more photographs of Picasso than any other artist, but there are lots of Miró and Braque, and many others.

In the exhibition we’re showing work by those artists she was friendly with and photographs by her and also by Man Ray. Then we’ve got one or two works by Joseph Cornell and by Henry Moore, who was obviously another great friend, of Roland’s in particular, but Lee photographed him.

There’s a Picasso show on view in one of our Chelsea galleries at the same time, so there’s quite a lot of work from that period being shown. It’s the fiftieth anniversary of Picasso’s death.

Have you ever thought of writing about your mother’s relationship with Lee and Man Ray and your memories of them?

MRWell, there are two projects. One is a book I’m currently writing, about my professional career. When I arrived at the Guggenheim in 1969, the whole staff was twenty-three people, from the director, Thomas Messer, to the head guard, and I became number twenty-four. And I feel that the museum world has changed so much that it’s worth writing about that period. When I tell my stories about going to see Miró in Palma and Josef Albers and Georgia O’Keeffe, people say, “You have to write it.” So I’m doing it and I’m having a very good time. The introduction is about growing up in Baltimore and my parents living in Europe and all that. And I write about the fact that in my family situation, my father was the boss and my mother’s past life was totally erased.

That’s one project. The working title is Curator at Large: New York, Paris, New York, because I’m also writing about the institutions, how they were run, and going from the Guggenheim, which had just a few more than twenty-four people when I left it (in 1983), to the Centre Pompidou, this big state-run museum where everybody is a civil servant, and where, to integrate, it was a lot more difficult [laughs]. And then going back to New York and having to navigate the trustee system at the Museum of Modern Art, which I knew nothing about.

The other project I would like to do is a little book about Lee and Tanja, just a small, elegant paperback. I have about fifteen Man Ray photographs of Tanja; I have Arnold Genthe photographs of her; I have photographs of her as a model in New York and in Paris. She also talked to me about what it was like working for Patou. I would like to discuss what it meant to be a professional photographer’s model in 1929–31. I think that Lee would be a major draw for the book, but it would be about their relationship. It would span a period of ten years.

RCOh, I think you must do both. That’s really interesting, to have experienced three different types of art institutions, but also the book about your mother and Man Ray and Lee. What comes across, looking at this period, is how collaborative they were. We know that Man Ray and Lee collaborated on solarization and other photographic themes and subjects. And sometimes it’s difficult to tell, you know, what’s by Man Ray and what is by Lee. If one regards the models, the subjects, as also collaborating in that—it could be a very interesting book.

Seeing Is Believing: Lee Miller and Friends, Gagosian, 976 Madison Avenue, New York, November 11–December 22, 2023