EDMUND DE WAALThere is a photograph of your darkroom in front of me, and the floor is full of cut-up images. It reminds me of how I have things pinned on my walls, and all the energy spent on things that get looked at, discarded, and replaced.

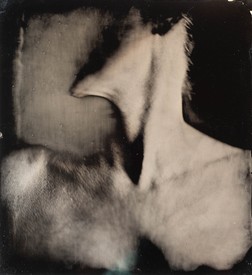

SALLY MANNI suspect aspects of how we work are very similar. For example, the nature and the importance of touch. All of these prints are physical objects; they’re not created on the computer screen. There is something messy and tactile about what we do.

EDWThere’s a wonderful phrase you used in Hold Still, when you’re writing about Cy. You talk about casual negligence, and these pictures of your darkroom felt quite the opposite: they resonated with energy, with how you were moving around your images.

SMOne of the things about Cy that always fascinated me, and even made me a bit jealous, is that he seemed to work with such extravagant joy, with an energy that almost burst out of him and onto the canvas. Making a photographic print is so precise and regimented; just a few extra seconds can make a difference in terms of whether a print is successful. My process seems so pedestrian, especially when compared to Cy’s. In your book The Hare with Amber Eyes, you described netsukes as an explosion of exactitude. That reminded me of Cy’s paintings. He was very precise, but his work often looks like an explosion. My work isn’t like that. Is yours?

EDWWell, I aspire to that. But there is something that interests me in the way you talk about instinct and judgments, thematic decisions that occur during your making of photographs, how prints change along the way, and all those precise and often intuitive reactions about when something’s finished or when something is still in process. There is an iterative knowledge gained over decades of working with an idea, with a tradition, with an art. And obviously there’s a parallel with working the way I do in clay—that exacting precision and the experience that has to come out in order to make very intuitive judgments the whole time you are working. Otherwise, it’s dead. And how you reach that casual negligence, that beautiful feeling of effortlessness when something feels totally alive. It’s great, and unbelievably difficult.

One thing I really wanted to hear about was the amount of time over which these photographs in Cy’s studio and home were taken. Because it strikes me that much of your work is about extended periods of time spent thinking about something and returning to it.

One of the things about Cy that always fascinated me, and even made me a bit jealous, is that he seemed to work with such extravagant joy, with an energy that almost burst out of him and onto the canvas.

Sally Mann

SMThe pictures span from 1999 until 2012, but it was a completely casual thing. Normally, when I’m shooting, I’m pretty passionate, and my heart rate goes up, but, at the same time, I try to think things through, often in a ponderous or methodical way. This project didn’t quite fit into my typical approach; it was almost whimsical, carefree.

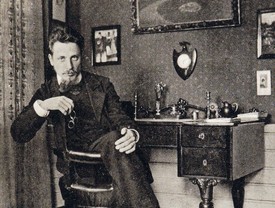

EDWYou use the word whimsical, which is very telling, because it resonates with a sense of intimacy. It begins by being in Cy’s space. He’s a friend. You’ve known him all your life. The project was not initiated by a gallerist or by a publisher. It emerges out of crossing a threshold between friendship and intent, even if it’s relaxed.

SMThat’s true and very unusual for me. It was so unfreighted; there was no endgame. The idea of exhibiting these images, or publishing them, didn’t occur to me at the time. It was just sort of a caress, an acknowledgment of his being there, right down the street in Lexington, which in itself was pretty amazing.

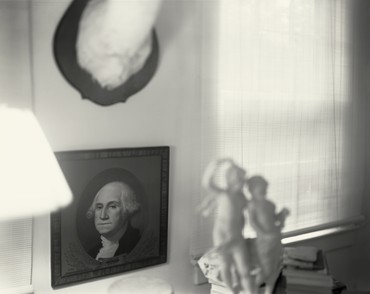

EDWAnd the studio in Lexington was unprepossessing, with low ceilings and slatted suburban screens in the windows.

SMYes.

EDWAnd that’s Cy in his hometown, making sculpture and paintings, taking photographs. And you know him; you love him; he’s been part of your life for as long as you can remember. I’ve been thinking about Cy and you and light there in Lexington, and comparing it in my mind to Gaeta, Italy, where Cy also worked, with the sea and the lemon trees. He has these two completely different places in his life, and he manages to make amazing work in both.

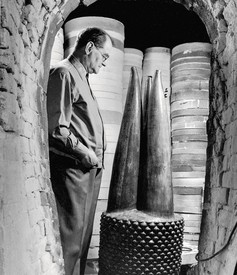

SMI know. This little building, which in my childhood was the of office for a gas company, then, somewhat fittingly, an eye doctor’s office, then becomes Cy’s studio in Lexington—very different from where he worked in Gaeta.

EDWLooking at the span of photographs over the dozen years in which you made them, there’s an extraordinary feeling of accumulation, that the studio begins empty and ends empty, but there’s this wonderful feeling of accumulation, of things coming in and almost nothing leaving, of Cy prowling the yard sales and just gathering objects. And you can start to see those things turn into something else, this strange way in Cy’s work that junk becomes sculpture, that reading becomes painting, that mark making becomes drawing, that graffiti becomes words. This accumulation very often condenses into Cy’s art, and then, along the way, he’s working in photography the whole time.

SMYes, his studio became an accretion of his enthusiasms in a way; it was almost volcanically rumbling with artistic energy. But all the same, there was a distinct sense of the mischievous in many of the objects he gathered, you know: the sequined hats and deer heads, just one thing after another. He had so much humor. And that particular aspect of his character is one of the things that I hope comes through in these pictures.

EDWIt absolutely does. There’s an extraordinary photograph of a ceramic frog—or some totally kitschy kind of ornament—you could spin it any kind of way into cultural history— but it’s still a glazed, kitschy ceramic frog that he’s bought from some yard sale.

You’ve taken the photograph in this wonderful way in which you let the frame provoke the whole time. You frame things so that there’s always a disjuncture in your images. They’re nonnarrative in that wonderful way in which they just stop and let you hang there.

There’s nothing casual about the way you think of photography, the way you take these images, the way you work with them. So tell me about editing. You produce a series of pictures: how do you then make the choice about which ones to develop, which ones to exhibit, which ones to leave behind on the floor of your studio?

SMWell, when we first chose the pictures for the book, I didn’t include those kind of goofy ones. That image that you just pointed out, which has the frog in it, that was the last one that went in. But Cy maintained a wonderful balance between the sublime and the ridiculous; he always played those two things against each other, at least in his personal life. Maybe less in his art. But I thought it was important for that picture to be in there, just to help people understand that aspect of his personality. He is such a revered figure with all these references in his art, but that’s only part of the story. He was also funny and irreverent and a little bawdy, and he always had a sparkle in his eye. I wanted that to come through.

there was a distinct sense of the mischievous in many of the objects he gathered, you know: the sequined hats and deer heads, just one thing after another. He had so much humor. And that particular aspect of his character is one of the things that I hope comes through in these pictures.

Sally Mann

EDWThis new series is a remarkable addition to your existing body of work because there are so many connections with other parts of your practice. And there’s a profound sense of affection in these images. One of the things that you always come back to is making pictures that are not melancholic, but which resonate with emotions, such as of leaving or death.

For instance, your meditation on the nature of mortality in What Remains contains some images of corpses, and they’re not sentimental, they do something totally different. The same holds true of the Civil War battlefields you photographed. How can you create something at the end of someone’s life, the end of their practice, of an empty space, as these recent photographs do, and not be memorializing or overdoing the gravitas?

SMWell, with the pictures of battlefields and bodies, I hoped to show that life goes on in all forms. In the case of the battlefields, you can sense the lives that were lost there and the pain of the people who were left behind. The bodies at the forensic study center were busily turning into fresh soil for the next dropped acorn. There is a sense of immutable, eternal life. And in these new works, there is a sense about Cy’s own continuum—the ongoing quality of his great legacy and his art—it’s not a memorialization, it’s a living thing.

EDWIt’s really important that you’re both totally forensic and completely involved, which is a remarkably difficult thing to do: balance both of those approaches at the same time.

SMWell, that is very nice to hear because one always hopes that there is some degree of transcendence. On one level, this work is a rather focused examination of an artist’s working place and the things left behind, but the hope is that it holds a greater sense of manifold truths about a life, through both the evidence and inspiration.

EDWEvidence is a very interesting word. In some ways, evidence is at the heart of your work, but evidence is a very complex idea. It is not straightforward. It’s an attempt to bring something into clarity and to hold it still.

SMBut you have to maintain the ambiguity, you don’t want it to be too clear. You always want to leave a question behind.

EDWAnd wanting an answer or having ambiguity is about how you use light, how you leave the end of an image hanging in white space at the edge of a page. You are never saying, “This is it.” You’re saying, “This is part of something; this is another attempt; this is another beginning.”

Artwork © Sally Mann