Brett Littman is the director of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, Long Island City. He has contributed news and commentary to a wide range of international art publications and critical essays to many exhibition catalogues. Photo: Don Stahl

Brett LittmanCould you both talk a little about creativity, and where the desire to continually reinvent yourselves comes from?

Daniel HummCreativity is something you need to pursue. In our case at Eleven Madison Park, it’s also something very collaborative. One thing I’m really pushing at the restaurant is that every human being is creative. There are people who say, “Oh, I’m not the creative type.” I don’t believe that. It’s like running: if you say “I’m not a runner,” you’re not a runner because you’re not running. If you start running you become a runner. I believe it’s the same with creativity: there may be limits to people’s creativity, but I think people should believe in it more.

BLBut it’s hard to embed creativity into a business model like a restaurant. With creativity comes a lot of failure—things just don’t work out. I mean, I run a museum, which is supposed to be one of the most creative workplaces in the world, and we just don’t have a lot of time to be creative since we get caught in the churn of our next show, our next catalogue, and our next public program.

DHWe change the menu four times a year. This is hard to do because it puts us on a schedule to be creative. We can’t just say, “Oh, I don’t want to exhibit next year,” or “I’m only going to do two shows next year.” The season changes and we need to be ready. Actually, the first step for every new menu starts four months before we plan to serve it. Every single person who works in the kitchen has to put forth an idea. It can be hard, because some people have never done that. But through this process it’s been amazing to watch how creativity is contagious.

Brad CloepfilFor Allied Works and for architects in general, every project is a reinvention. For me creativity is a muscle you have to exercise. I think in architecture today there’s a level of banality out there because people don’t push themselves to be creative.

BLWell, I guess architects develop a signature style and then you’re asked to go ahead and make that building again and again. That’s what the client wants.

BCCreativity is more like trying to understand what the questions are. People come to us to make buildings and usually they come to us for all the wrong reasons. It’s really interesting: they think they know what the function is about, they think they have an idea about the site, about the way they use buildings, or the way they see themselves in buildings—their references are so limited. They aren’t thinking about what’s possible. Creativity is getting them to clear the slate of their preconceptions, and one’s own preconceptions, to try to figure out what the real questions to ask in this project are.

BLSo you’re a form-follows-function kind of guy.

BCNo, it’s not about function at all. It has to do with what architecture can do in this particular case.

BLI see—it’s about context.

BCRight. Because architecture can do a lot of different things: it can solve problems, it can create insights, it can heighten emotions, it can do all kinds of things. You don’t really know what role architecture can play until you clear out a lot of the preconceptions about it.

DHI want to say one more thing about creativity: it’s very important in what we do, but it’s only one part of it. I believe cooking is really a craft, and for a long time you just need to pursue that craft—learn how to make a perfect consommé, learn how to sear meat perfectly, learn how to make a braise, a stock—there’s a way to do it. I’m coming from that school of classic training. Creativity only comes into play much, much later.

BCI totally, totally agree.

DHBeing a chef is a craft. Cooking is a craft. A lot of chefs are craftsmen and that’s the highest form of cooking, in a way. Creativity really applies to a very small subgroup of restaurants, and that’s good.

BCI like the word “discipline”—discipline as a methodology, or a goal, but also one’s own discipline, which is built on rigor and knowledge. Ten years ago I wouldn’t have had the knowledge and the confidence to do the type of work I’m doing now. I wouldn’t have had the staff that could propose crazy things and know that we could figure out how to do it.

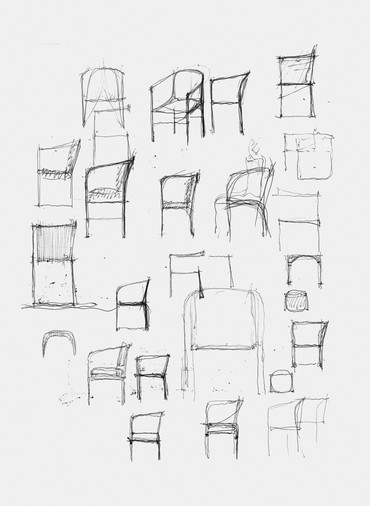

BLBrad, I know you draw a lot. How does drawing fit into your practice as an architect?

BCFor me, drawing is everything. It’s how I think. I’m at a table with some charcoal and I just start to draw. It’s how I find the architecture. My drawings aren’t representational, they’re more like plans or sections. I want to find presence in my drawings—materiality, light, earth—something tangible. I guess it’s kind of like breathing to me.

BLDaniel, do you draw?

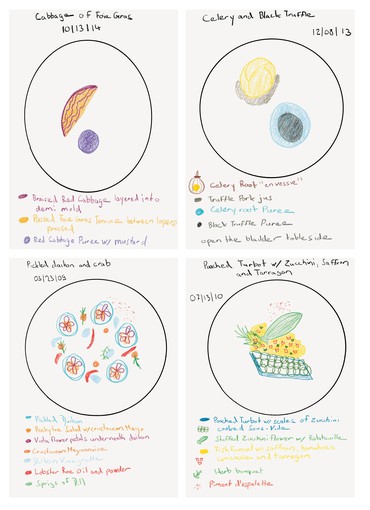

DhWhen I was seventeen I worked for a chef in Switzerland who had two Michelin stars. He was this mad man, he would smoke in the kitchen and drink beer, he had his dog in the kitchen with us. Every day he would make a new menu depending on what he could find fresh in the markets or from our purveyors. The guy was unreal. He was one of the most creative chefs I’ve ever worked with. Things you usually need to prepare for he made in the moment. At the end of a shift, my head was spinning. We worked sixteen hours every day. When you came in the next day he’d say, “Do you remember what we did yesterday?” No one could remember—every day so much genius was lost. One night when I got off my shift and went home, I started to draw the dishes we had made that day as a way to document them. When the chef asked if anyone remembered what we had done the day before, I was able to say yes because I had my drawings. Pretty soon after, he started to let me run the kitchen, because now I understood what we were doing and had this memory. That was about twenty years ago. Since then I’ve continued to draw and it has really unlocked my own creativity.

BLHow has culture in general—music, art, film—had an impact on your thinking?

DHI was always drawn to art. I remember going to a lot of museums when I was very young.

BLWere your parents artistic?

DHMy dad is an architect so I was always interested in objects, furniture, and museums. I remember falling in love, when I was ten, with Monet’s Water Lilies. But when I started cooking, I really became focused on cooking. I collected cookbooks, I traveled the world and everywhere I went I’d go to restaurants—for probably fifteen years I thought about food only. I learned a lot and evolved a lot as a craftsman.

Along the way, though, there were works of art that really had a big influence on me. One was Picasso’s eleven drawings of bulls, which go from detailed to just a couple of lines. That really got me thinking about how one could be subtractive in one’s approach but still represent the essence of the thing. In fact I’ve always been drawn to Minimalist artists, I guess because my overall aesthetic at home and at work is simple and minimal. I always think it’s harder to leave something out than to put something in.

I also remember in 2006 I went to see a Lucio Fontana show at the Guggenheim Museum with a friend who’s very knowledgeable about art. When we got to one of Fontana’s slashed-canvas pieces he said, “This is probably the most important piece in show.” I knew he was right, I could feel it—I didn’t understand the work at that point but I was curious about it and really wanted to figure out why it was important, so I read about Fontana and came to better understand how radical the move to cut the canvas was for him and for art history.

BCBefore I went to architecture school I thought I wanted to go to art school, but there was really no museum culture in Portland [Oregon], where I grew up, so I didn’t have a strong background in visual art. When I went to Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture it was in the mid-’80s, and all of those Minimalist guys were showing in the galleries and museums. I remember seeing Ad Reinhardt’s black-on-black paintings for the first time. I think that was the first art book I ever bought. Man, those black-on-black paintings blew my mind. I also listened to a lot of minimal music by Steve Reich and saw dance performances by Trisha Brown—I felt I’d walked right into an amazing moment in New York cultural history.

One thing I feel strongly about was that this work was not reductive. I think that’s a misconception. I felt that all of this work was really about concentrating things into the most powerful and potent form. Chef, when I think of your food, it’s the exact same way. You look at that simple form on the plate. I’ve told a million people about your carrot entrée: it’s just a disk of carrot on a plate, but when you taste it, it explodes your brain. You can’t even imagine carrot can do that, you never encountered a carrot like that before—one that could be transcendent like that. It’s probably one of the best dishes I’ve ever eaten.

BLPhilosophically, what do you think the goals of cooking and architecture are today?

DHThe goal of cooking is to feed people. That’s the core. But when people come to Eleven Madison Park, I want them to feel present. I want them to be able to engage with each other and create a personal world that they can inhabit for three hours. Everything we do is really to enhance their experience and their togetherness. We want them to be able to talk to each other, so we don’t have waiters constantly interrupt diners every two minutes with information about the dishes. We do things where they have to open something to get the food. Even the way we make and serve our bread—we bake it together, so people have to break it with their hands to serve it to themselves or share with others.

BLSo you want to build a sense of community in the dining room. Slow things down for busy people and make them savor and think about what they’re eating.

DHToday, our mission is, we want to be the most gracious and most delicious restaurant in the world.

BCFor me the goal of architecture is to create a profound experience. It’s about wonder, about creating wonder. And what wonder does is change your context and reference points.

One of the reasons Eleven Madison Park is such a wonderful platform for Chef is that he has this gorgeous and historic room. You walk in there and you’re awestruck. You cannot believe that you’re going to get to eat in a space like that. When a space is beautiful and powerful and quiet, it allows you to shirk your day-to-day worries and stresses and opens you up to new experiences.

It has to be beautiful. For me beauty is when it’s minimal, when it’s organic, and when it feels effortless.

Chef Daniel Humm

DHWhat’s been amazing about working with Brad is how much I’ve learned—a lot about my food and a lot about architecture. I think Brad is more an artist than an architect, that’s what I love about him. You’re very open, you get excited about things, and you have a childlike sense of wonder.

What I learned from Brad very clearly is an appreciation of the elemental. It’s not minimal, it’s elemental. Before we worked together I wasn’t totally aware of that term, or hadn’t really thought about it much. But today I think of my food as being much more elemental than minimal. When you’re minimal, you just try to take away as much as possible, but when you’re elemental, there’s nothing too much and nothing too little, it’s just right. That’s the balance you strike so well with your architecture, and that’s what I want to do today as a chef—be elemental, not minimal.

BCWell, one other thing about Chef is that what he serves also has to be beautiful. There’s this dish with foie gras and cabbage. It’s a total piece of sculpture, one of the most beautiful things. I think beauty plays a huge role in both of our practices, which is another reason why we’re not minimalists. Ultimately, our work still has to resonate and have that presence and evoke those kinds of emotions and that kind of engagement. It has to be beautiful.

BlCan we talk about some of the specific architectural choices you made at Eleven Madison Park?

DHBrad has been a friend for a long time now and has come to the restaurant and always loved it. When we signed a new twenty-year lease, we realized we had to redo the kitchen. But to redo the kitchen we needed to close the restaurant for three months. So then we thought we needed to touch up the dining room and pretty soon we were on the phone with Brad and involved in a full-scale renovation of the whole place.

Even before you got into the details of the job what struck me was that you were in love with the room and wanted the room to retain its main characteristics. I think what you proposed in your first sketch was very close to what we ended up doing: we made the room more proportional, created two different levels, and made the entrance to the dining room through the middle rather than having it on the side.

BCYes, I’ve known Chef and his business partner Will Guidara for many years and love the restaurant. So the opportunity to work with them was a dream come true. They’re the best at what they do in the world right now. Then there was also that beautiful room that people have known for years. So inherently you have the challenge of dealing with people’s memories of a place and the problem of changing their perception of that place when you renovate it. You have to be very careful with that.

We started off doing a lot of research of historic restaurants in beautiful buildings. We looked at dining on railroads and planes. For me restaurants are amazing places. There’s the memory of all the great rooms in New York City, like the Four Seasons, or the great restaurants in London and Paris. Diners at Eleven Madison Park have probably eaten in some of those places, so they carry their own memories to dinner.

I loved being able to work on all of the textures and materials, the experiences of engagement. How are you going to feel in the chair? How does the texture of the banquette affect you? What should the quality of the light at the table be? We were shooting for a sense of intimacy to complement Chef’s ideas about dining at Eleven Madison Park. I was really excited to play some small part in this continuum: to make an exceptional space for food, service, and the experience of dining is really an honor.

BLIntimacy is hard to achieve in a big room like that, no?

BCYes, that was something we really had to think about. Will has amazing thoughts about service and what the restaurant is providing for its guests, how it wants to accommodate them and how it wants them to feel. I’d say it’s more like thinking about theater than about architecture.

BLChef Humm, you commissioned a lot of new artwork for the restaurant. Can you talk a bit about these projects and how they came about?

DHProbably the most important piece I commissioned was by the artist Daniel Turner. I had seen an installation where Daniel pulverized a cafeteria into dust and sprayed it on a wall [Particle Processed Cafeteria, 2016]. That got me thinking about what I could do with my kitchen when I pulled all of the tools and equipment out for the renovation. This is where I’ve lived for the past twelve years, so there’s a lot of emotion tied up with that stuff. Daniel proposed that we go to Polich Tallix Fine Art Foundry in upstate New York and melt everything down into a sculpture. That sculpture turned out be the step that you use to go up to the second level of the dining room. I have to tell you, when I watched my kitchen being melted I was really moved.

BCI was totally game to include Daniel’s piece in the program. The step is a perfect metaphor, a way of stepping on and over the history of Eleven Madison Park.

DHI wanted to pay tribute to the past. When I create my food, there’s always a sort of “one foot in the classics” feeling to my cuisine.

Another important commission is the chalkboard work by Rita Ackermann. In the old Eleven Madison Park there was a huge painting of Madison Square Park by Steven Haddock. Rita decided she would redraw and erase and then redraw this image again on six large blackboards. In the end, she let me pick the one I wanted. There are thirty-six layers of erasing on the one we installed—which I liked, because it felt like a new beginning to me. It’s also the piece that most reminded me of her, and her of me. There’s also something very personal about this work: I went to a Rudolf Steiner school growing up, and the idea of a chalkboard as a place for learning, teaching, and creating was very present for me.

We also worked with the artist Olympia Scarry to commission 11×11. She noticed some older stained-glass panels that were in the restaurant before the renovation and that faced east to west, so she decided to fabricate, with a master glass-maker in Zurich, a new series of painted and stained-glass works that are now installed in the transom over the entryway on a north-to-south axis. The work for her is about shifting perceptions, which is what we’re also trying to do at the restaurant.

I have two friends who are very involved in the art world who told me the key to these commissions is that you have to make them personal. I think in some ways that’s why they work in the space. They also give us nice stories to tell our diners when they ask about these artworks.

BLHas the renovation and reopening of Eleven Madison Park made you rethink your core values at all?

DH I’ve recently come up with four fundamentals that I think really define my cooking today.

Number one: it has to be delicious. Delicious is not something you need to think about or understand. It’s instant.

Number two: it has to be beautiful. For me, beauty is when it’s minimal, when it’s organic, and when it feels effortless. There was a time in my career when I wanted my dish to look like it took fifteen chefs to put it together with tweezers. Today I don’t want that. Today I want it to look like it fell from the sky.

Three: creativity. Every dish has to be creative—it has to add a new element, a new technique, a surprise, a flavor combination you haven’t had.

Four: intention. A dish has to have a reason for being. It can be as simple as three ingredients grown next to each other on a farm, it could be a childhood memory, it could be historic preference, it could be inspired by an artist’s work, but it has to have something that explains why it exists.

I feel for the first time in my life I’ve found myself as a chef. Every dish that you look at in the restaurant, it’s clear where it came from. I’m really excited about the future because I’m at a new beginning and I’ve just found this new language that I haven’t fully gotten to use yet.