Mary Gabriel is the author of five biographies, the most recent being Madonna: A Rebel Life. Her previous book, Ninth Street Women, won the 2022 NYU/Axinn Foundation Prize for Narrative Nonfiction and the 2019 Library of Virginia and Virginia Museum of Fine Arts’s Art in Literature Mary Lynn Kotz Award.

Carol Kino is the author of Double Click: Twin Photographers in the Golden Age of Magazines (Scribner). Her work has appeared in publications including The New Yorker, WSJ magazine, the New York Times, The Atlantic, Slate, Town & Country, and just about every major art magazine, including Art + Auction, where she was a contributing editor.

Mary GabrielSo Carol, tell me, where are you at this moment with your book?

Carol KinoOh, the book is pretty much finished; they’re not letting me make any more changes.

MGI find it so terrifying at that stage, because it’s impossible to write a book and not make mistakes or see places where you’d like to add or subtract a word, if not a paragraph. Given your history as an art journalist, where did this idea come from?

CKWell, I wrote a couple of small stories about a show by one of the McLaughlin twins and her husband, the Harper’s Bazaar photographer Leslie Gill, and through that I got interested in the entire family, because the other twin had also married a photographer, whose father had been a really famous photographer in the Jazz Age. Then my agent and I were trying to come up with a good subject for a book and I knew that I wanted to focus on midcentury America in some fashion. I was intrigued by this idea that there had been many female photographers in midcentury who had successful lives and careers, in contrast to the painters—as you know [laughter]. I’d written so many stories about painters of that period who were downtrodden and struggled for success, and I didn’t want to write that story again. The original proposal was to write about a group of women during this period, and the editor who acquired it said “Write about the twins.”

MGI think that makes a lot of sense. You pay homage to their birth and their early family in the book, but really the gist of the story is the ’40s and ’50s. Why did you decide to do that?

CK[Laughs.] This is going to sound terrible, but I really didn’t set out to write a full biography. I love writing profiles and illuminating cultural scenes, but I’m less entranced by the idea of defining an entire life. I’m sorry to have to admit that in this discussion!

MGNo, I think it really works, because so often people feel obliged to continue a person’s story well past the time when they’re actually doing anything. I think what people want to know about is the person in their heyday. I do admire biographers who write what I call soup-to-nuts biographies, which contain every important date, every scholarly detail, but I think for the kind of book you wrote—because it isn’t just a biography of two women, it’s a cultural history—you needed to limit the focus to their lives in that period.

CKAnd there wasn’t a massive amount of information about their lives anyway, because they were focused on taking pictures and that’s where much of the biographical information came from. I spent a lot of time looking at the pictures they took, and at the notes on the back of the pictures, and piecing the story together that way. There were threads I could follow and build on from a few interviews with them, but they were discreet about their personal lives. So the book became sort of a cultural history wedded to the shape of their lives.

I’m so curious about what you did with Madonna. I’m reading the book now and I’m interested in your technique, and how you managed to make it seem as though you were interviewing her, and yet you didn’t. How did you do that? Did you read every single interview and look at every single video?

MGWhen I write a book, I—and it drives everyone in my life crazy, I mean, truly crazy—I just literally give up my life and live that person’s life full-time. In Madonna’s case it’s no exaggeration to say six to nine hours a day, seven days a week for five years. In that time, I read and listened to every interview with her I could come across. I read every interview that her colleagues and family and compatriots gave. I watched all of her performances; I listened to all of her music. I mean, there was so much information that it wasn’t a matter of trying to piece together tenuous threads; it was almost having too much. I wasn’t able to interview Madonna myself, despite five years of trying, but I think the book works anyway. What I did was treat her as a historical figure, which I think actually makes sense because she exists so far out of our normal day-to-day life, on a plane apart. So I just pretended that she was out there on another planet and I’m telling the story that I can access: a historical story as a cultural historian. What I tried to do, and I hope it works, is that when I’m writing about her in 1983, at the start of her career, for example, I quote an interview from that moment, so that a reader hears a young Madonna talking, not Madonna at the age of sixty remembering what she was like at twenty-three.

Also, in all my books, I want to try to immerse the reader in the person’s life as much as I possibly can. So I try to remain out of it completely, and just have the characters talk to the reader and set a scene in the way maybe a novelist might. Unfortunately, as a result, my books are always huge, because, as you know, you can’t tell a life story with all the context around it without adding pages and pages and pages. I always opt for the book I want to write as opposed to the book I should write, which is a saleable 400 pages. I just let it rip and remain poor [laughter].

Each biography is . . . a mind meld, a meld of the person doing the writing and the person they’re writing about. So it’s not really a biography at all, it’s a portrait.

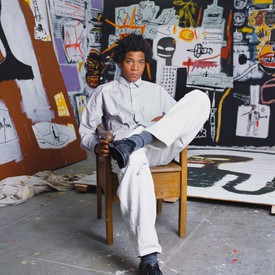

Mary Gabriel

CKThat’s what’s so interesting about your books: as a reader you feel you’re walking through the world you’ve captured—it’s the fullness that pulls you in. I couldn’t read Ninth Street Women [Gabriel’s book from 2018 on the lives of artists Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler] when I was working on my book because I just—

MGThere was so much overlap.

CKYes, and when I finally read it, I realized there was even more overlap than I’d initially thought! Occasionally I’d look at it to do something like check a detail about Mary Abbott, who also appears in my book; the twins knew her as Mary Lee. But I didn’t realize that Wilfrid and Elisabeth Zogbaum appeared so often in Ninth Street Women, too.

MGAnd Hans Namuth; so many names came up in both stories.

CKYour book was so intimidating whenever I looked into it, because you painted this massively full picture of everything going on at the time. I had to keep reminding myself that your book was much longer than mine would be. But once I’d finished mine, I was able to sit back and appreciate yours.

MGIt’s just a different approach. Though in reading your book, in the Depression and war-years sections especially, I still got the feeling that, without going into the excessive detail that I did, you gave the reader the sense of what it was like to be living at that time. Also, that unbelievable period during the war years when women found their voice because men just weren’t there—the kind of photographs that your characters were taking during the ’40s were incredibly advanced for that time.

CKI think so.

MGThey would still be considered innovative today. And then I realized, well, women were speaking artistically in the ’40s because they were given a platform. Then that platform more or less disappeared for thirty, forty, fifty years, and now it’s back. There’s this nice return of those images, I find.

CKLooking through the magazines, there was this year, 1947, when everything changed: the men started coming back, and they got the credit for all the advances women had made. Women were just supposed to—

MG—go back to the home.

CKExactly, and look up to the men like these great saviors. Of all the innovations women photographers made, the most striking to me was the blurry action snapshot photograph. Men got the credit for dreaming that up after the war, but that had already been done by women for a few years, by Franny in particular, who had been hired by Alexander Liberman almost out of art school precisely for her ability to capture movement in a still shot. Same with other fields: Cipe Pineles, the visionary young art director of Glamour, championed this new naturalistic photography and was the first woman to be inducted into the Art Directors Club, but when Liberman arrives, she’s just disappeared from Condé Nast and he doesn’t even remember that she’s been there.

MGIf you look at women in this time, the ’40s, they were in power, and in the ’50s they were just pissed [laughter]. This actually leads to Madonna: part of the reason I wrote that book was that I wanted to do another art book, and she chronologically is the daughter of that period of women from Ninth Street, and you know, we are too. The women in the ’40s tasted power, and in the ’50s most of them had to relinquish it. But they gave birth to this generation of daughters whom they—what’s the word?—not subconsciously but surreptitiously imbued with a sense of the power they’d lost. In other words, they gave them lessons in empowerment that society wouldn’t have. Madonna got the message at a moment before it was entirely corrupted. In the ’60s and early ’70s, she was just a kid and she heard the message, “You can be powerful, you can do what you want. You can be what you want. You’re as good as your brothers.” And she believed it.

You said you started with an idea of maybe a group of women and then you narrowed it down to the twins. When you’d done that, did you have a clear picture of what the book was going to be?

CKI did and I didn’t. I always wanted it to end with them marrying, in this sort of ironic way, because that’s the way many novels about women end, with the marriage. I was also thinking of The Makioka Sisters, Jun’ichiro Tanizaki’s novel about postwar Japan. I haven’t read it since I was in college, but it’s about a family’s efforts to marry off the eldest daughter so that her younger sisters can be married. The book ends with her marriage, which is presented as a triumph but in reality is not ideal. So in my book I wanted to present the twins’ respective marriages as the ending, yet not an idyllic ending, and not the end, because they still had to resolve their careers, which went on long past their husbands’ deaths. And of course their lives and careers had very different trajectories because of the men they married.

MGSo you knew how it was going to end, but I often find I don’t know the shape of the book or I don’t really understand the story until I’ve finished and then I go through and read it. Did you have that experience?

CKYes. I would say I had this vague idea of the shape it would take, but getting it to tie up neatly in a bow and having it feel right didn’t happen until it had all been written. There were so many threads I was dealing with, starting with the twins and their relationship with each other, which was very difficult to navigate, and their complicated relationship with Jimmy Abbe, the photographer with whom they were both involved before he married Kathryn. Were they competitive? Were they loving? How much of what they said about each other, and what their family and friends said, was true? That was so difficult to figure out. There was so much intricate reporting needed to define all of that before I got to the end. And then there were a lot of threads about what had happened, in society and how America had changed, that I was also trying to work out, with way more original reporting than I’d expected. I took pains to make it read lightly and amusingly, but there are many deeper layers all the way through.

How do you decide on a new project?

MGOkay, well, what interests me in a biography is taking a person or a period of history that we think we know everything about and telling a new story. So for example, let’s talk about Karl Marx. I was living in London and I came across a magazine article about Marx’s two daughters. He had three daughters and two of them committed suicide and I thought, Whoa, that’s an interesting story. So I started looking around for something about them, and I realized that in the extensive material about Marx—the books on him could easily fill a library, and a sizeable one—no one had really bothered to talk about Marx the man. Who was this guy and who was his family? Every person of significance, whether it’s an artist, a philosopher, a warrior, a revolutionary—if they have a family, that family impacts them. And with Marx in particular, in Victorian times your community was very small and it was largely made up of the people directly around you. Marx had been depicted from the head up, I like to say; he was all brain. But I wanted to tell the rest of him, Marx the body, Marx the man. And to do that I had to tell the story of his family. So I just shifted the narrative a bit. Here’s a guy who everyone in the world knows by name, but how much do we really know? And if you just look at him slightly differently, it changes everything.

Then with Ninth Street Women I did the same thing. With the Abstract Expressionist era, even if you don’t know anything about art you know about Jackson Pollock, you know about drip paintings, or can at least picture what they look like. But that was such a narrow and limited portrait of that time. So many years ago when I met Grace Hartigan, one of the painters I wrote about, she told me this unbelievable story of what actually happened then and how women were a big part of it.

CKWhat was the story she told you?

MGShe just talked about her life during those times, and that it was this great party, basically—this convergence of poets, painters, composers, musicians, filmmakers, photographers, everybody living in Manhattan or as far away as Long Island and creating in response to what had been happening around them and to the war, which had also, unbelievably, been left out of the Abstract Expressionists’ story. By the time we started learning about the movement, it was Clement Greenberg’s version of that history and it was entirely theoretical. He eliminated the fact that these artists had just watched the world be destroyed, both in war and by the atomic bomb. Where do you go from there as a painter? What’s the subject? So the subject became themselves.

Grace also talked about a lot of women who had been completely left out of the telling of that era. And as I’ve said, at the moment of the most revolutionary period in American art history, women were essential. Lee Krasner and Elaine de Kooning were some of the prime forces in that movement, and for a long time no one paid attention to them. I decided to take a moment in art history, in cultural history, and make it come alive in a new way by looking at it from a different perspective. And with Madonna it was the same thing. Like Marx, everyone knows Madonna, and everyone has an opinion.

CKThat’s what’s so interesting.

MGAnd I mean, what’s it based on? It’s based on insane headlines that have nothing to do with her. So once again, I said, Okay, well, let me just go back to the start, which is what I do with all these people. I go back as far as I can to the source material and start from scratch, and I try not to be influenced by what’s been said about them. I just want to read and study and learn about what their contemporaries said at the time and who they were at various points in their lives. I think the person who emerges from this book is surprising even to some of her superfans, because I’m not treating her as a celebrity, which is the Madonna we all know, I’m treating her as basically a performance artist and a cultural revolutionary. Very few artists can actually say they’ve changed the world and I think she can really lay claim to that.

I remember when I wrote my Marx book, I was living in Italy and a lady down the road, she was so great, this old British lady, I told her what I was doing and she said, “Oh god, does the world need another book on Karl Marx?” And it was a good question. But with biographies, when I hear a comment like that, I think of a Cézanne still life. Cézanne will paint an orange one way and Van Gogh will paint an orange a completely different way and Picasso will paint an orange a third way. Each biography is that way too. It’s a mind meld, a meld of the person doing the writing and the person they’re writing about. So it’s not really a biography at all, it’s a portrait. You and I could have the same source material and we’d come up with entirely different stories about the same person. I think that’s why I always bridle when people say a book is a definitive biography, because that just doesn’t exist: it’s just my interpretation or your interpretation, and some are more accurate than others, some are more interesting than others, but they’re all valuable. We have this tendency to think of a biography as something cold and factual, but there’s a human behind the pen—although maybe when AI starts writing biographies, that will no longer be the case.

CKThat will be the definitive biography [laughter]. But to your point, there have been two biographies of Condé Nast and they’re very different from each other and explore different aspects of his life and personality, I think depending on what the biographer was interested in. The Caroline Seebohm biography of Condé Nast, which is the earlier one, went much more into Glamour as the magazine he created from scratch, and that was of course very interesting to me because I was writing about that time from the perspective of young women. Nobody had treated these magazines for young women really seriously before because they were regarded as beneath contempt, which they shouldn’t be because young women control many aspects of our society. I was writing about the moment when marketers and powerful people began to realize that. That moment should not be disregarded, as anyone who has a teenage daughter must know, I think.

MGYou know, that’s what really surprised me in your book: I’d never considered for a moment that there was a fashion-magazine industry during the Depression. I mean, that just seems unbelievable. But in fact it was thriving.

CKDuring the war, too. The magazines were using their paper rations to create more and more magazines for young women because that was the thriving market. I really had a hard time in the beginning getting photographers to take my project seriously, because of the fashion and young-women’s-magazine aspect of it, which really pissed me off.

MGReally? I’m surprised.

CKEarly on, I tried to get in touch with photographers to find out how these old cameras worked. It’s surprising how many books or stories one reads where they don’t explain to you how something really works. I wanted to explain how these cameras function and how they changed throughout the period—not in muddy language but in really clear language. And at the beginning, I could not find guys who operated these old cameras and were willing to explain them to me, because they thought, “She’s writing about these dumb wealthy women who were fashion photographers who didn’t have a brain in their heads,” which was totally not true when it came to the twins—they excelled academically to the point where their achievements always made the papers, and they had to work because their mother lost everything in the Crash. It kind of infuriates me to think about it now. It took so long to have this taken seriously as a project, even when I had a [New York Public Library] Cullman Fellowship [laughs].

MGWell, welcome to Madonna’s world.

CKOh yeah, I’m sure.

MGEven as the biggest pop star on the planet, she still wasn’t taken seriously.

CKAnd she still isn’t now.

MGExactly. How many years does it take? Apparently forty isn’t enough. What do you hope a reader walks away with?

CKHow all the achievements we associate with the rise of feminism in the United States in the ’70s were actually going on in the ’30s and ’40s, and then got squashed completely—even though people issued warnings at the time about there being a war on women. And now we’re seeing exactly the same thing happen again. I was also shocked to find in my research that women during this time were far more sexually free and sophisticated than I would have imagined—or at least a certain type of urban woman was leading a fairly free life in the late ’30s and in the ’40s. Maybe they continued leading it in the ’50s, but they didn’t talk about it, and it was all hidden beneath this propagandistic veil of the nuclear family. Then we had to really fight like hell to get it all back in the 1970s and now it’s being squashed again. I really hope the reader sees that and doesn’t just think the book is only about fashion [laughs]. What about you?

MGWhen I did Ninth Street I had a specific person in mind I was writing it for, and I wanted a specific reaction: I was writing it for young, mostly women painters, but male painters too if they were interested, and I wanted them to see themselves, because before that you couldn’t look at the history of art and see someone who looked like you as a painter and think, “Well, how did they do it?” Not, “I’m going to paint like that person,” but “How did they manage their lives?” I wanted that reader to come out of the book thinking, “Okay, here are some cool-as-hell women who I can take courage from, and I can see what they did and the mistakes they made and how they navigated being a woman with the idea of motherhood and husbands and patriarchal society.”

Then for Madonna, I aimed for a broader audience, because I want people, first of all, to react on the level of, Wow, what a story, because it’s unbelievable. You couldn’t make it up. And I also want them to develop an appreciation for her if they didn’t have one, and if they were already fans to come away having learned something. The Madonna we know about from the press is a media-created character; Madonna the artist and social revolutionary is so much more complex and so much more interesting. More broadly, I kind of use people as avatars through periods of history and she for me is my avatar for modern US history. So ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, 2000s—how did our world change? It’s changed massively. Was it always for the better? No. Is it better now? No. Are there ebbs and flows? Yes. And how does Madonna affect that? Where are we now? And what can you learn from her life about where we are now? I’d like people to take a look at Madonna’s life as a kind of guide through modern history to see where we’ve come from, where we are today, and to have the strength that she had to make sure that we don’t go backward. It’s a cautionary tale. And I mean, if I learned one thing from her it’s, My god, you have to have courage in this life because if you don’t, you’re not going to get anywhere and you’re not going to change anything. You’ve got one life—maybe, unless you believe in reincarnation—so you’d better make the best of it, and that’s what she’s done. I think readers might get a little dose of that inspiration. So Carol, I expect you to be a dancer and a singer by the time you finish the book [laughter].

Carol Kino, Double Click: Twin Photographers in the Golden Age of Magazines (Scribner, 2024)

Mary Gabriel, Madonna: A Rebel Life (Little, Brown and Company, 2023)