As an actor, comedian, author, playwright, screenwriter, producer, and musician, Steve Martin is one of the most diversified performers and acclaimed artists of his generation. Martin’s work has earned him an Academy Award, five Grammy awards, an Emmy, the Mark Twain Award, an AFI Lifetime Achievement Award, and the Kennedy Center Honors. As an author, Martin’s work includes the novel An Object of Beauty, the play Picasso at the Lapin Agile, a collection of comic pieces, Pure Drivel, a bestselling novella, Shopgirl, and his memoir Born Standing Up.

Fred Myers, Silver Professor of Anthropology at New York University, has been doing research with Pintupi-speaking people on their art, their relationships to land, and other matters since 1973. Myers has published two books, Pintupi Country, Pintupi Self: Sentiment, Place and Politics among Australian Aborigines (1986) and Painting Culture: The Making of an Aboriginal High Art (2002).

Louise Neri has been a director at Gagosian since 2006, working with artists and developing exhibitions, editorial projects, and communications across the global platform. A former editor of Parkett magazine, she has authored and edited many books and articles on contemporary art. Beyond the exhibitions she has organized for Gagosian, she cocurated the 1997 Whitney Biennial and the 1998 São Paulo Bienal, among numerous international projects. Photo: Lin Lougheed

Louise NeriWhy, when, and how did you engage with the work of contemporary Indigenous Australian artists?

Steve MartinMy first encounter was in 2015. An article in the arts section of the New York Times presented a photo of an imposing man, Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, in front of his paintings, which surprised me, bewildered me, and prompted me to bicycle downtown on a warm summer day to investigate. [My wife] Anne and I were able to acquire one of the paintings, and for three years I didn’t realize it was part of a greater movement. Later, I was struck by a single photo of an Indigenous Australian painting on the Internet. Then, as each click led me further into the field, I became enchanted. I was face to face with an art I had never seen before. I started building a small library on the subject and found the story of Indigenous Australian art compelling. I eventually contacted several of the books’ writers, and they were able to help and guide me to legitimate sources to acquire other works.

LNHow did your initial interest develop into a more concerted effort to establish a collection?

SMI really don’t like the term “collection”; “bunch of stuff” is more accurate. Still, we have assembled about forty paintings by Indigenous Australian painters in a careful effort that seems to have some coherency. It has been a stirring exercise to discover and recognize what our specific interests are in this field. I was excited to discover a sophisticated and fully formed body of art that was new to me and unlike anything I’d ever seen—a 60,000-year-old art history compressed into a mere fifty years—and to see how it had migrated from a specific translation of sacred symbols into an internationally recognized movement that is both emotional and intellectual.

LNDoes your collection have specific parameters?

SMI realized that the early Indigenous Australian paintings, from the 1970s onward, have been splendidly collected and catalogued by insightful collectors and museums. My interest, piqued by these complex early paintings, made me look at the evolution of the work, and I focused on works made after 1984. I was also struck by the coincidental relevance of these paintings to other contemporary art.

Most of the paintings we own are Western Desert works on canvas. They come from the terrific Papunya Tula art center in Central Australia. Dedicated art centers dotted throughout the region serve the Indigenous Australian community, protecting the artists, cataloguing works, and so on. These are vital for the authentication and provenance of works.

LNDo you have a wish list?

SMVan Gogh’s Starry Night.

LNAnd with regard to Indigenous Australian art?

SMWe own several works by Emily Kame Kngwarreye from different periods, but we don’t have an early “dot” painting of hers. We’re so grateful to the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection at the University of Virginia for lending Emily’s Hungry Emus (1990) to the exhibition. Emily didn’t start painting until her late seventies and worked feverishly for seven years until her death, changing styles almost every year.

LNHow does contemporary Indigenous Australian art relate to other modern and contemporary art that you live with?

SMDesert art is isolated. I gathered from my reading that it sprang from thousands of years of tradition, but was disconnected from and uninfluenced by the outside world. Yet it isn’t outsider art. It has coincidental relationships with other forms of contemporary abstract art, but it differs significantly in that all Indigenous Australian paintings on canvas are stories citing specific events and journeys, and they’re infused with an intense connection to the local landscape. They never participate in the irony that suffuses so much contemporary art.

LNWe’re living in a time of rediscovery, cultural accountability, and new appreciation in art and culture, where we’re looking at the overlooked, where restitution is a live issue, and where the global conversation is gradually expanding to include art from many different cultural contexts. As a recent but impassioned enthusiast, what do you feel might the place be for contemporary Indigenous Australian art in the broader context of contemporary international art?

SMI once thought I knew the perfect art show. One would simply select the best pictures from the canon, and everything would be wonderful. New discoveries and probing scholarship have unearthed artists who worked under duress and hardship, with little or no public recognition, at an equivalent artistic level to their more famous counterparts. These relatively unknown artists now stand tall among the canonized giants of the art world, and the shift in focus has been quietly revelatory. I believe that Indigenous Australian paintings will eventually hang together with all the great modern and contemporary artists.

Desert Painters of Australia

Text by Fred Myers

The works in this exhibition all emanate from a single, basic cultural tradition of image, decoration, and performance, and more specifically from an emergent art movement among Indigenous Australians that has drawn on that tradition. The show contains paintings from several different Indigenous communities and by speakers of different languages, but their underlying cultural forms are shared. What is called the “Western Desert art movement” began concretely with Indigenous Australian men living in a government-managed Central Australian community known as Papunya. These men developed the practice of painting with acrylics on a two-dimensional surface, eventually Belgian linen, drawing on their own preexisting practices and images, and on their imaginings of ritual and ancestral creative activities in the landscape.

The paintings, I was told very early on, were “true”—that is, they drew their authenticity from the ancestral stories that they continued to represent, and from the places in the landscape in which these stories were primally enacted and which were formed by the ancestral actions. Places, stories, origins—all these inspired the first generation of painters to put their images into two-dimensional form to show to outsiders. This transformation—from body and ritual painting, rock art, and sacred objects to two-dimensional forms—was from the beginning a creative invention, a transposing of traditions into different and new forms, striking for their beauty and variety. One would be misled to refer to this work as either traditional or nontraditional; that is quite beside the point. The artists strongly assert that it is drawn from, inspired by, and transmits the authority and truth of ancestral revelations, notwithstanding the human variety of creative mediations and instantiations of “truth.”

Such artworks are part of a history, an aesthetic and conceptual movement that has changed its forms from its beginnings—in 1971, with the men who came together around the opportunity provided by the schoolteacher Geoffrey Bardon at Papunya—to the present. This movement has been a surprising and inspiring history of invention, innovation, and novelty that has made its way onto museum and art-gallery walls throughout Australia, Asia, Europe, and the United States—a history all the more compelling for the fact that many of its creators began their lives as hunting and gathering people in one of the world’s most demanding desert environments.

The works in this exhibition belong to what might be seen as a third or fourth wave of innovation. They were painted for the most part after 1990 by men who were middle-aged in the early 1970s, when the movement began; by women of an age at which they might have been married to those original painters but who began painting later, in the 1990s; by men who were young in the early 1970s; and by a still younger generation. These were the waves of gendered and generationally different engagement that brought new forms into being. This information might be useful when looking at their works as part of a history: the virtuosity of these works cannot be appreciated through their passing parallels with other formal conventions in modern and contemporary art. These are inventions that took place locally, as Indigenous artists sought to attract broader attention and to communicate what mattered to them through visual art.

The Artists

One of the few remaining artists of the first generation, Willy Tjungurrayi was born in 1932 into a family still living in a traditional way. After his early middle age, he lived in various settled Pintupi communities and by virtue of this timing and history was deeply embedded in those communities’ ritual knowledge and the beneficiary of the extensive range of rituals that they knew and practiced. The painting in the exhibition, Untitled (2001), is from a place with which he was closely identified, the large dry salt lake known in English as Lake MacDonald and in Pintupi as Kaakurutintjinya. The lake has mythological origins in a story in the ancestral Tingarri cycle, which tells of the connected travels of groups of young male novices through the country. This particular story deals with a marsupial cat—Kuninka, an ancestral being—and its punishment of two ceremonial initiates who had neglected to share the meat from a hunt. Kuninka unleashed a hailstorm on these young men, killing them and turning the vegetation of the area into a burned-out area—a dry salt lake. The two initiates turned into water snakes. Many of the Pintupi painters from the Papunya Tula arts cooperative have painted Kaakurutintjinya; Tjungurrayi’s work is an extraordinary abstraction of it, and of the story about it. The white dots represent the hailstones that fell on the lake, depicting them in all their sheer number, magnitude, and expanse. Tjungurrayi’s hand does not practice the careful, exacting mark-making of some of the younger painters but rather shows the expressiveness with which his generation more typically painted.

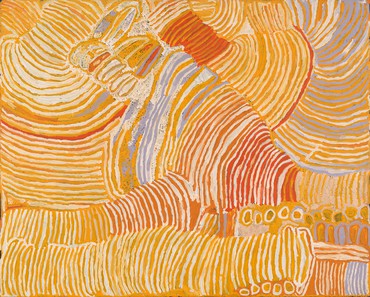

The show’s two paintings by Makinti Napanangka (1930–2011) represent the story Kungka Kutjarra (Two women), which takes place at Lupulnga, in the Sir Frederick Range, her father’s country and the place where she grew up. Napanangka didn’t start to paint until she was well past middle age, in the mid-1990s. She had a deep interest in women’s rituals, which in her community were focused on the pair of ancestral women known as Kungka Kutjarra. These women created the rocks at Lupulnga and their activities are reenacted in a women’s-only ritual typically involving dancing with woven strands of string spun of human hair (often cut in mourning). The bold and flowing lines of color in both paintings represent the movement of these fiber strands, which take the form of women’s nyimparra skirt coverings in the ancestral story but are held as strands in the hands of dancers in the ritual. The paintings replicate visually the power identified in the hair strings. Napanangka herself participated vigorously in the ceremonies, reenacting these ancestral events. She found great pleasure in reproducing this ritual engagement in paint on canvas.

After the death of her first husband in the early ’60s, Naata Nungurrayi (born 1932) and her young sons made their way to Papunya at a time when the last remaining Pintupi who were living an independent life were migrating out of the desert. At Papunya, she remarried, and one of her sons—Kenny Williams Tjampitjinpa—became a significant painter before she did. Nungurrayi, like many of the women artists, really began her life as a painter in the mid-1990s, when most of the older generation of men had passed away. This new generation of women coming to the practice of painting in acrylic brought a great burst of energy to the art movement: although their paintings remained concerned with the country, its landscape, and its ancestral stories, they introduced new imagery and new organizations of paint. Nungurrayi’s painting Untitled (2010) represents Karilywarranya, in the Pollock Hills in Western Australia, where she grew up. The painting incorporates the story of the ancestral rock pythons (carpet snakes, kuniya) said to have visited this place. The painting shows the kuniya’s decorative coils along an ascending path at Karilywarra, surrounded by what Nungurrayi conceives as the verdancy of the local vegetation; after rain, water collects in gullies and rockpools, and the area comes alive with vegetation, birds, and animals, as represented in the brightness of color and the rough extravagance of the dotting.

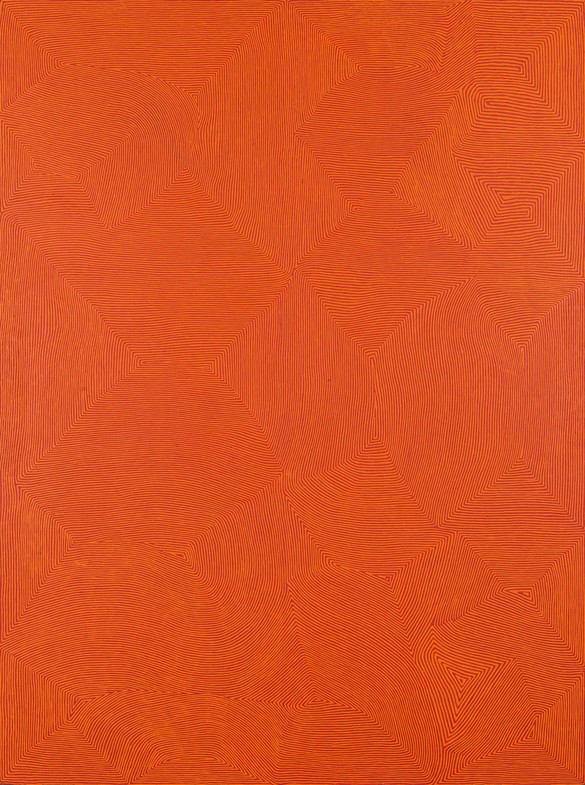

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri (born c. 1958) is significant as a member of what became known as the “Pintupi Nine,” or the “first contact group,” one of the last Indigenous groups to move into contact with Australian society, in 1984. His work has been shown in such major exhibitions as documenta 13, in Kassel, Germany. Tjapaltjarri started painting in acrylics in 1987, after observing his relatives painting in the remote community of Kiwirrkura, in Western Australia, where the art cooperative known as Papunya Tula (from its origins at Papunya settlement) had become well established with the movement of former Papunya-area residents to the west in the 1980s. Because of his special status, his earliest paintings were set aside as a distinct and significant collection, which was purchased and donated to the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Tjapaltjarri started his career with the acquisition of ritual knowledge and the making of designs in various mediums as part of the activities of his life before leaving the bush.1

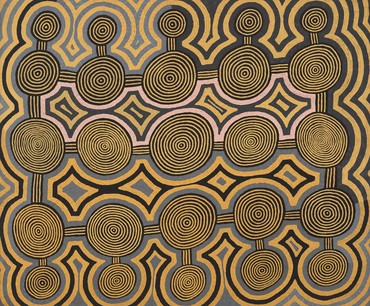

Like the other painters in this exhibition, Tjapaltjarri paints his country, very often Lake Mackay (Wilkinkarra), a huge salt lake, or Marruwa, the more intimate site where his family often lived. Untitled (2015)—probably a painting of Wilkinkarra—is a brilliant example of how he has evolved from his initial deployment of the motifs of circle and line, drawing on an iconography of body decoration and sand-drawing most common in the first generation of painters. Currently, his work involves large canvases of rectilinear forms produced out of lines of dots. These dots have their origin in local practices of male body decoration, especially in the ceremonial performance of stories of the Tingarri cycle (in which performers enact ancestral beings), and rock art. In the acrylic work, though, their use has been elaborated and extended in allover treatments and as the basis of delineating actual forms. The rectilinear patterns themselves are culturally significant for many of the painters in the show: these keylike interlocking forms resonate with incised designs on wooden shields and spear-throwers, as well as with a variety of ritual objects marked by incising or carving rather than paint. Dots, it should also be understood, are themselves forms deriving from the ancestral realm. They have been elaborated in the painting movement, but the word used to refer to them is restrictive, “men-only,” and like the dots themselves is said to be “dangerous.” As the painting movement has developed, women have been allowed to use these forms, which are significant as signs or indices of ancestral power and presence.

In the painting of Wilkinkarra, we can imagine that Tjapaltjarri emphasizes the ancestral power of the place through the optical effects of the dotted figure-ground relationship. In much of Indigenous Australia, the effect of “shimmering” brilliance, as Professor Howard Morphy has called it, is identified with ancestral power. In ritual activity, often at night and by firelight, the movement of dancing figures bearing body painting and decoration produces a kind of shimmer or flash. The painting creates this flash with its own resources, but the form of the design resonates with the designs of sacred objects and emblems that represent the salt lake’s mythological activities. As such, it is a sign of a sign, and by drawing from the signification of the place, it brings forth Tjapaltjarri’s own excited experience of the story and its enactment. In this painting the appearance of abstraction offers the viewer the experience of engaging with the ritual form of the place without revealing the specifics of the ritual, which are restricted or secret.

The ancestral story of Wilkinkarra is often reenacted in teaching initiates about the travels of the Tingarri novices, and the overt features of the story are known to most. Briefly, it involves a group of traveling women who reach a hill where they see two older men. They notice kangaroo meat there, however, which implies that young men are somewhere nearby; they find the young men, have intercourse with them, and are happy to have them as partners, but the older men are angered by this transgression, which interrupts the ritual control of the younger men by the older ones. The old men light fires to burn out the area, killing all the young men and women. The salt lake is the ash from the fire. There are many more features to this story, and to hear Tjapaltjarri tell it is to experience the excitement and intensity packed into his painting—of a mountain exploded and reduced to a flat plain, the revival of the women from death, and their subsequent travel back to Northwest Australia. To see the painting is to have this experience conveyed through the flashing and shimmering form of the mesmerizing rectilinear design, bringing to the viewer the power of ancestral creativity as well as the artist’s attachment and emotional connection to place.

Ronnie Tjampitjinpa (born 1943) was a young man when the first generation of painters invented “Western Desert acrylic painting,” or “Papunya Tula painting,” as it was initially known and developed in that specific community. Tjampitjinpa came into his own as an artist in the late 1980s as part of a “second wave” of aesthetic development. His painting led the way in its focus on very bold imagery and the accentuation of strobelike figure-ground effects in the design. Rather than emphasizing an iconography directly expressing the activities of ancestral figures in the landscape, and relying on color, iconic features, and their arrangements as the principal aesthetic devices, Tjampitjinpa’s newer work presents optical effects that resonate with the revelation of ancestral body decorations by flickering firelight. It often involves a field of large concentric circles arranged against a dotted background, but with no clear indication of the possible significance of these circles other than their indexical relationship to body decorations. The dots bleed into each other, becoming only vaguely discernible, to hypnotic effect. Some ritual decoration worn by men celebrating Tingarri stories takes the form of concentric circles; a work such as Tarkulnga (1988) abstracts the presence and revelation of these treasured designs, in this case in relation to Tarkulnga, a site in Western Australia. This aesthetic effect performs, rather than narrates, ancestral power and the experience of men like Tjampitjinpa in relation to the places with which they are identified. The emphasis is on the forms of the designs themselves, made bigger and more focused; the dots and the more figurative elements of body and ritual decoration become the subject matter.

Yukultji Napangati (born 1970), a close relative of Tjapaltjarri’s, was one of the group who left their traditional hunting-and-gathering life in 1984. She was only fourteen at the time, and as a younger woman, she began painting later than the older women, such as Nungurrayi and Napanangka. Napangati is quiet and observant, as much an active forager in the environment as a painter, and her paintings reflect her passion for the country. She seems to have begun painting at Kiwirrkura with her husband at the time, Charlie Ward Tjakamarra, and she has developed a style of work involving intense and careful dotting, often luminous, on large canvases. There are few overt features in her paintings, and when she identifies a particular feature, it is constituted of a pattern of dots rather than of direct lines. Her subject matter is the mythological ancestral women whose activities and travels created many places near the community of Kiwirrkura and in other areas of her country. The paintings Ancestral Women at Marrapinti (2017) and Untitled (2017) present two places connected through the travels of these women, locations where they stopped to make marrapinti, bones used to pierce the nasal septum and worn as decoration, a custom derived from the ancestral story and practiced as a kind of rite of passage for young women in historical times. Napangati explains a circular or oblong feature and its extension toward the corner as a cave in the hill at Marrapinti and the path down from the cave, but also as a rock thought to be the nose of an ancestral woman who turned to stone. The flowing lines of meticulous dots that cover the painting, shifting in hue from yellow to orange, mark both the expanse of sand hills that stretch over the desert country and the marrapinti that numerous ancestral women made and used. For Napangati, the painting expresses her active dwelling in this familiar and known environment, rather than a mere depiction of it.

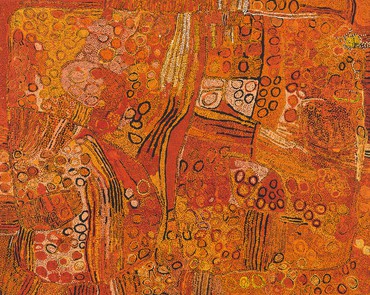

Tjumpo Tjapanangka (1926–2007) was closely related to most of the Pintupi painters whose works are in the show, although he lived not in Papunya but in the Western Australian community of Balgo. Painting developed at Balgo later than at Papunya, hundreds of miles to the south; in fact it was inspired by the developments there, through visits between relatives inhabiting the two places, but the Balgo painters used brighter pigments, bolder colors, and, often, rougher execution. Tjumpo’s painting in the show, interestingly, is of Wilkinkarra, the same place or story as one of Tjapaltjarri’s large canvases. The two artists shared a relationship to this place. Tjumbo’s painting, however, predates much of Tjapaltjarri’s work, and combines rectilinear and circular forms. Tjumpo’s rendering of Wilkinkarra draws attention to two mythological or ancestral snakes said to have gone into the ground there. The snakes are marked by two circular forms, and three thick yellow lines appear to indicate pathways connecting to the passage of these ancestral figures. One might assume that the choice of a white background resonates with the color of the salt lake. The story of Wilkinkarra connects Indigenous people over a broad area of the Western Desert, and a number of stories intersect here, so that the activities of the snakes who passed through are adjacent to the areas of the Wilkinkarra story represented in Tjapaltjarri’s citation of the fire that created the lake, following a different line of ancestral beings who traveled through the area. Tjumpo’s painting uses the rectilinear designs associated with some of the men’s ritual activity, as Tjapaltjarri’s does, but does not sustain the optical effect of figure/ground so much as the effect of light on the salt lake.

Named after his beard or whiskers, Bill Whiskey (c. 1920–2008) was a Pitjantjatjarra man, living in the small community near Mount Liebig in the Northern Territory. Whiskey was a renowned ngankari, or healer, and came to painting later in his life. His paintings relate directly, in fact in an almost unmediated way, to drawings that men of his age once made for anthropological interlocutors with crayons on butcher paper. In his painting Rockholes and Country near the Olgas (2007), circles indicate the rock holes and significant hills of the places he remembers, mapping out “country.” Whiskey’s paintings depict his own country, around the area of Mount Olga and Ayers Rock (Uluru). Although he painted long after most of his contemporaries, his paintings resonate with the work of an earlier generation at Papunya of which he was a part, the generation of Tjungurrayi. with the multilayered dots unevenly applied, noting the flows of water, vegetation, and landforms giving form to his sense of being in place.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye (1910–1996) is the most famous Indigenous Australian artist; her work has been exhibited in Europe and Asia as well as throughout Australia. Emily, as she was known, began painting at a late age in the Alyawarra community of Utopia, and is celebrated for her rapid and systematic exploration of different styles and formal inventions. At Utopia in the late 1980s, Emily and her compatriots adopted the practice of painting with acrylics that had begun at Papunya and spread to other communities in Central Australia. Emily’s paintings identify themselves with women’s ritual activities and with the life force of her region’s vegetation. Often, the painted lines offer the forms of women’s body painting, which is applied to the shoulders, arms, and breasts in broad strokes—ritual activities identified with the creation of the land. Emily’s early dot paintings, which drew on her experience with traditional batik fabric-printing, were remarkable for their differences from the acrylic-painting movement as it was developing elsewhere. Over time, her paintings became more and more gestural, reduced in their detail and thus quite abstracted and liberated in their formal qualities. As far as can be determined, her inspiration was always her country and its ancestral figures, as it is for the other artists in the exhibition, but her expression of this concern evolved into more and more simplified marks. The art historian Terry Smith has argued for understanding her as a modernist painter, placing her abstraction in relationship to her life experience of modernity as the dislocation of traditional life. Smith admires her work as making pictorial space anew.

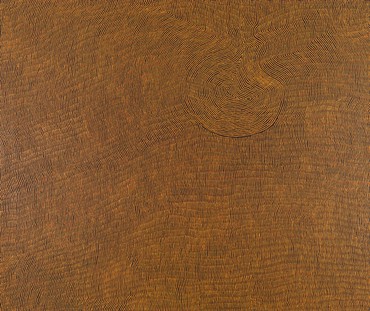

George Tjungurrayi (born c. 1947), from the Pintupi people, has been represented in solo exhibitions in Australia and included in the Biennale of Sydney, where a suite of his paintings was exhibited both flat on the ground and on the wall. He is invested in the ritual heritage he learned as a young man and particularly in the stories of the Tingarri cycle, so tied to various places in his country, but he has chosen to express his relationship to these places without revealing anything of a secret nature. His paintings, like his own self, are kept tightly controlled and rigorous, and emanate from some intense introspective space. He has been recognized as the originator of a style of pared-back linear composition, painted in single lines (not dots) laid down with careful precision, a style corresponding closely to his way of being. Tjungurrayi’s works are celebrated for their organizations of meticulous designs in rectilinear complexes. The painting in the exhibition identified as Untitled—Kirrimalunya (2007) shows Kirrimalunya, a site that in the stories was created through the activity of two boys with strong healing powers (ngankari) who traveled through the area. At Kirrimalunya they gathered mungilpa seeds, to be ground and roasted in seed cakes. The place is marked by claypans, shallow depressions where water gathers in the spring and where mungilpa grows in abundance after rain. Looking at Tjungurrayi’s many renderings of it, one can recognize that the shimmer of his lines captures something of the surface of these temporary waters. Like Tjapaltjarri’s paintings, Tjungurrayi’s work forms part of the late, linear wave of the Western Desert art movement, and his use of lines rather than dots, producing interfaces of two colors, seems to allow him to paint as if investigating the space and limits of the canvas.

Special thanks to the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection, University of Virginia, and D’Lan Davidson, Melbourne, Australia.

1Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri would have been familiar with incising designs on wooden implements including spear-throwers and sacred objects, making spears, boomerangs, and dishes (mainly with introduced metal tools), the use of ocher and vegetable fiber in ritual body decoration, the manufacture of ephemeral objects out of local materials for ceremonies, and the making of sand drawings as part of storytelling; and he would have seen rock paintings in caves.

Desert Painters of Australia: Works from the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia and the Collection of Steve Martin and Anne Stringfield, Gagosian, 976 Madison Avenue, New York, May 3–July 3, 2019

Photos: Rob McKeever