Anton Corbijn is a photographer, film director, and designer. Amongst many awards, he was given the highest Dutch cultural award, the Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds Prijs, in 2011 for his contribution and influence in the world of the arts. His work can be seen in museums and galleries, and has been the subject of more than fifteen books. Photo: Stephan Vanfleteren

Natasha Prince has been working with Gagosian for over ten years, coordinating sales of works by artists including Roe Ethridge, Jeff Koons, and Andy Warhol, among others. Prince joined the gallery after a career in the fashion industry as a model, during which she worked with many top fashion photographers, including Mert & Marcus, David Sims, and Corinne Day.

Ivan Shaw is the corporate photography director overseeing the Condé Nast Archive. Previously, he served as photography director of Vogue. Shaw has contributed to numerous books and exhibitions, including Extreme Beauty in Vogue and The Editor’s Eye, is a coauthor of Around That Time: Horst at Home in Vogue, and has presented lectures on the history of fashion photography in the United States and England.

Three Things: The Work of Anton Corbijn

By Ivan Shaw

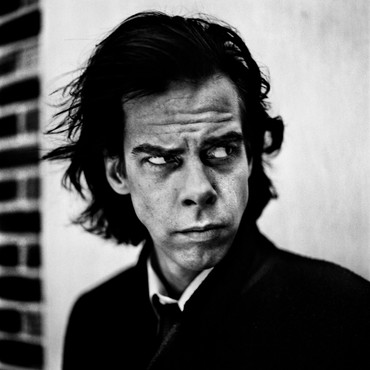

There are three things one should know about Anton Corbijn to better understand his work. The first is that he was born into a religious community in the town of Strijen on the island of Hoeksche Waard in the Netherlands, his father being the local pastor. The second is that he is very tall. In fact, R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe believes that Corbijn’s height makes the photographer see the world from a different perspective. The third is that he works very fast. Corbijn has been known to do entire photo sessions in just a few minutes. These three factors together, plus a great eye, have helped make Corbijn not only one of the preeminent portrait photographers working today but also one of the great music video directors and a highly sought-after feature film director.

Growing up on an island as part of a religious community, Corbijn felt like a consummate outsider. Photography became the bridge that connected him to the rest of the world. After hearing the Beatles for the first time, Corbijn became obsessed with music. As a teenager, he wanted to attend a local concert but was painfully shy. The solution: borrow his father’s camera so he could get up close and take pictures of the band. If he was busy taking pictures, he wouldn’t have time to think about being alone in a crowd.

The pictures Corbijn took that day and the enormous body of work he has produced over the past forty years, primarily for magazines like New Musical Express, Rolling Stone, and Vogue, are a revolution in perspective. His camera angles and focal points can seem almost unimaginable. It’s hard to understand how he got there. Moreover, his palette of intense contrast and grit in black and white or deeply saturated colors is uniquely his own.

Corbijn works fast; in fact, he thrives on the pressure of being forced to create quickly. He believes that “if you don’t have much time, you concentrate all of your energy on the moment and it’s far more focused.”

After spending time looking at Corbijn’s work, particularly his 2015 book Anton Corbijn: 1-2-3-4, one realizes that the intensity of Corbijn’s feeling, the uniqueness of his vision, and the speed of his documentation have created a portal through which we see beneath the surfaces of many of the most significant figures from the past four decades.

Corbijn’s close-up portrait of physicist Stephen Hawking wearing mirrored sunglasses captures the radical intensity of Hawking’s mind and wipes away his physical infirmity. Allen Ginsberg stares out a window, newspapers stacked in front of him. We feel him contemplating his life’s work as a poet and writer and his place as an outsider and revolutionary.

Corbijn’s oeuvre extends far beyond the work he has done for magazines and for the music industry. He has pursued a number of fine-art projects, including 33 Still Lives (1999), which explores the world of the paparazzi genre and ideas around authenticity, and a.somebody, strijen, holland (2002), which delves into Corbijn’s relationship to celebrity, in the form of self-portraits as a deceased rock star, and his own experience growing up in Strijen.

If one had to place Corbijn’s work in a fine-art context, it could be seen as embodying at once the elegant simplicity of August Sander’s People of the Twentieth Century and the raw intensity of Robert Frank’s The Americans.

To say that Corbijn’s relationships with the musicians he photographs run deep would be an understatement. Corbijn has worked with Depeche Mode and U2 so extensively that each of the bands has referred to him as its fourth and fifth member, respectively. His numerous portraits of recording artists have come to define the genre in many ways. In Corbijn’s #5 series, we see LL Cool J from a distance, still a man of the streets, yet firmly grounded and finding his way in a big world. An image of Kurt Cobain wearing women’s sunglasses and an overcoat seems to signal the last vestiges of a life that was soon to pass. The band Coldplay heads out into the surf, ready to face the unknown together. Patti Smith lies in a chair and raises her arm to shield her face in a failed attempt to guard herself from Corbijn’s penetrating gaze. These are the people who created the music we listen to, and to see them through Anton Corbijn’s eyes is to know them.

An Interview with Anton Corbijn

Natasha PrinceAnton, as I am British, your artwork means so much to me. What inspired you to first pick up the camera, and was there a particular shoot that helped build your passion to lead the way, or a particular artist?

Anton CorbijnMy start as a photographer was very simple and not based on any knowledge of it or wanting to create a masterpiece. I was obsessed with the music world and tried to find a way to be part of it. By borrowing my dad’s camera once, and taking it to a free daytime concert in our town, where I took a few shots, I became convinced that this was my calling. Only then did I start to have an interest in photography itself, but for a long time musicians were my only subjects. My initial references were record sleeves and music magazines, and then gradually the photographers who worked in music, such as Jim Marshall, David Gahr, and others. From there, I became more interested in photographers outside that field. Who doesn’t love Robert Frank or Dorothea Lange or Richard Avedon, etc.? There is a long list of great artists.

NPYour images have captured the culture of British music so well. When did you first move to London, and why?

ACI moved to London in 1979, as I loved the music that came from the UK and at the time especially the band Joy Division, who had just released their first record. They were the first band I photographed upon arriving in London. I was in the UK from 1979 till 2008, after I made my film about the singer of Joy Division [Control, 2007] and lost so much money I had to sell my London home. So Joy Division were my bookends for my London stay, in a way.

NPFrom the late 1970s you worked for the London-based New Musical Express [NME], and you did most of their covers. Can you tell me how you got to work with them and a bit about the photo of David Bowie wearing a loincloth?

ACI did a few small things for NME when I arrived in London—back to the drawing board, really, as I had to do live photographs initially—but then after three months I did covers for NME and became their main photographer for five years. As it was a weekly magazine, and an important one at the time, the amount of work was huge and I was shooting many covers and stories every month. It’s how I met U2 and Depeche Mode, as well as countless others, of course. I shot the Bowie image you mentioned when he was doing theater in Chicago as the Elephant Man. I knew an NME journalist was going to interview him, but he had specifically said no photographers, so I was not asked by the NME to go. I did, however, buy a cheap ticket to get myself to Chicago with the journalist and persuaded Bowie’s PA to let me take a few photographs. And, gentleman that David was, he gave me a few minutes to take that shot. Eternally grateful to him.

NPYou went on to take a lot more photographs of Bowie, and we will all be eternally grateful for the music he left behind! One of my favorite images is the one you took of Joy Division for Unknown Pleasures, which is the last photo of Ian Curtis before his death in 1980. How did this image come about? Was Ian’s death a surprise to you?

ACThank you. That photo means a lot to me and has grown to mean a lot to other people too. Well, as I said, I came to London to be closer to where that music came from, and when I finally arrived, in the last few days of October 1979, I noticed that Joy Division were playing at the Rainbow [a Finsbury Park venue, now a religious center] in early November. I managed to get myself in there and afterward packed up the courage to go backstage and introduce myself to their manager, Rob Gretton, as an important photographer from the Netherlands, and ask, could I do a photo with the band at a location the next day? That worked, and they came to the tube station near my basement rental; it was the only tube station I was familiar with, of course. It was a cold Sunday morning and they were standing outside the tube station shivering in their big coats with just shirts underneath. Typically English to not dress for winter, but they were there and up to do a photo. My idea for the shot was their album title Unknown Pleasures, and I wanted them to walk away from me as if on a trip to unknown pleasures, inside this tube station’s staircase. It looked great as an environment to shoot in, and for decades I didn’t let on where this was photographed, as I was afraid people would copy this photo, but since the station, Lancaster Gate, has been redone and doesn’t look anything like it anymore, I have spilled the beans. Anyway, it looked great when Ian looked back, and that became the shot. All over in five minutes, and they shook my hand, something they refused to do when I arrived and offered my hand, so they were probably pleased it was only five minutes.

Afterward, I showed the photo to NME and to some other magazines in Europe, but no one was interested, as you could not see the faces. Of course when Ian died everyone loved the image. Weird how importance and beauty get attached to images due to outside events. So when Ian died it became the cover of NME and started to be the image people associate with the band.

The band were, at the time, a month or so after I shot their photos and had sent them contact sheets, the only people who loved the photos. They invited me over to Manchester in April 1980 to hang out during the making of the video for “Love Will Tear Us Apart,” and that is when I shot the solo image of Ian looking very introspective. That was a few weeks before his death. Again, that photo became a lot weightier because of what happened. My English was not very good at the time, so I never had a full conversation with him and had no idea about his state of mind, so yes, his death came as a total surprise to me.

NPSo far we have mentioned two incredible lost musical legends. You directed the brilliant Ian Curtis biopic Control. Would you ever make a movie about another artist you have worked with?

ACI will not say, “Never ever,” but it is hard to take distance. With Control, I was able to take distance, as I had only been part of their lives on two days, so nothing too emotional, but I felt close enough, so that worked. My films after Control were very different on purpose, to prove to myself that I was a filmmaker. I was very fortunate to be able to work with great actors like Philip Seymour Hoffman, George Clooney, Dane DeHaan, Willem Dafoe, Robert Pattinson, Nina Hoss, and others, all thanks to Control.

NPIt’s written that you’re like the fourth member of Depeche Mode, and you now have a new Taschen book about to launch with a history of images of the band. How did you first begin to work with Depeche Mode, and what made you stick with them?

ACWe met in 1981 for a cover shoot I did for the NME and initially that was it. They were in their early days, and for me they were far too poppy. They or their record company tried at least twice to get me to do press photographs over the following years but I turned them down. Then in 1986 I was asked to do a video for them with the stipulation that it had to be done in the USA, as they were on tour and that was the only possibility. That, funnily enough, was for me the only reason to say yes, as up to that point I had never done video in the USA, so I went there and made a video. Then almost a year later I was asked to do the next video, and quite organically it became a close collaboration and I realized their music, which had changed since the early days, and my visuals worked really well together. I became more and more involved. I’ve designed all of their stages since 1993, and I’ve been responsible for designing the album sleeves, their logos, etc. It is a very unique trust that exists between us.

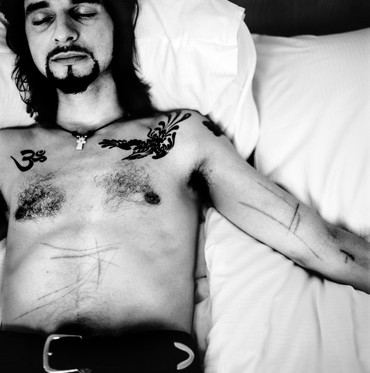

NPTell me about that image of Dave Gahan on the bed. You captured him in such a vulnerable state, it’s clear you have a trusting relationship. He didn’t mind you sharing this picture of him looking so depleted?

ACIt was taken in the darkest period of his life, and during the darkest tour they ever did. The shot is of him back in the hotel room after a concert where he threw himself into the crowd. Scratches are from that event as well as from self-harm, I think. The image is Christlike, and that is why I printed it. I feel it goes beyond the person portrayed. Of course I didn’t publish this photograph till many years later, when the drugs period was way behind him and he was able to look at that period as the past. This is also part of the trust—I get into situations other photographers don’t get into, but I will not use it to betray friends.

NPYou have a long-standing working relationship with U2 as well; what’s going on now, and what’s your favorite thing about Bono?

ACHe is a very positive person. He is also far more creative than people realize. I just did a little photo book that will accompany the rerelease of U2’s [2000] album All That You Can’t Leave Behind later this year.

NPHow do you feel about the music industry changing so drastically since the ’70s and ’80s? And if you had to find a band in today’s world to work with long-term, who would it be?

ACI don’t think I would have gotten into this profession in this day and age. It was a great start for me in the ’70s, but I don’t recommend the hardships I went through for today’s music industry and the short-lived careers of people in it. The last band I felt I wanted to be a visual part of was Arcade Fire, and that started in 2005. I am not a fan of the music “industry”; for me it was always the people, the musicians who appealed to me. I was just lucky that a lot of people I wanted to work with survived this long and became the forces they are.

NPWhich female artist means the most to you, and why?

ACI would say Nina Simone and Joni Mitchell. Their music is meaningful and has an intensity I relate to.

NPPeople call you the greatest rock photographer in the world, but you don’t like to be labeled that way, do you?

ACIt narrows the way you judge a photograph—I really try to take photos that go beyond a person’s notoriety, and although I don’t always succeed, of course, it is what I aim for, and that way we can relate to a fellow human instead of a celebrity in the photograph. But if you already label the photo a certain way, it will be looked at a certain way. That is why I call myself a portrait photographer. In any case, I have, for the last thirty-plus years, done series on painters, actors, and others. The world in front of my camera is a lot broader than just music—that is more the past, I’d say.

NPIs there anything you’re working on now that you would like to tell us about?

ACWell, I am in the throes of finishing this massive book on Depeche Mode for late-autumn release, and I also have a catalogue coming out for my late-September show in Knokke [Belgium] that is called MOØDe, which shows my work more related to clothing. Some fashion designers, some shoots I did for Vogue, as well as musicians, painters, and models who wear either no clothes or something that looks purposeful, be it just long black coats or hats or whatever. Interesting to put my work in that context. It is about clothing rather than high fashion.

NPHow has the pandemic changed you? Has it had any impact on your future artistic vision?

ACWe have to see how it changes the way a portrait photographer can work in this new reality, and I have little intention of flying around or visiting the USA currently. I think that this period has given me time to reflect and realize I have been running around like a maniac for decades. I find that in situations where you are cornered, you can become very inventive and creative, so let’s see what comes out of it.

Artwork © Anton Corbijn