Gillian Jakab is an editor, online and print, of Gagosian Quarterly and has served as the dance editor of the Brooklyn Rail since 2016.

Bebe Miller first performed her work in New York in 1978 and formed the Bebe Miller Company in 1985. Since then she has created over fifty dances for the company, which has performed them in the United States, Europe, South America, and Africa. A professor emerita of dance at Ohio State University, she is the winner of a United States Artists Fellowship and of a Doris Duke Artist Award, and was honored by the Kennedy Center as a Master of African American Choreography.

Cynthia Oliver is a New York Dance and Performance Award (Bessie)–winning choreographer whose work incorporates textures of Caribbean performance with African and American aesthetic sensibilities. She currently serves as associate vice chancellor for research and innovation in the humanities, arts, and related fields at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Gillian JakabIt’s so wonderful to have the two of you in conversation. What has kept you busy during the pandemic?

Cynthia OliverI’m sitting in the midst of all of my videotapes and books. I’m using this moment to get all of the tapes digitized.

Bebe MillerWow.

GJThat’s important for dance-history preservation!

COIt’s been a long time, I’ve wanted to do it for years. Recently I came across a DVD of Bebe’s piece Necessary Beauty that I’d forgotten I had, and I reached out to Bebe. I watched it and I was brought to tears because it was so beautiful. My body felt like I could do it again. We were working on that over a great distance and over a considerable amount of time. Bebe would record our rehearsals and then send me the recordings.

GJWhen was that?

COWe premiered in 2008, so we were working on it in 2007. I’m in this beautiful barn at [the Massachusetts dance center] Jacob’s Pillow. I’m dancing by myself so the pressure is on. Bebe is directing me—I’m improvising and she’s talking as I’m moving. Even now, while watching, my stomach is up in my throat from the nerves of having Bebe Miller watch me and make comments while I dance.

BMAll choreographers start with ideas about time, space, and energy. I’m looking at those elements in a certain way, but I’m also looking at what it is that you are doing, and what you’re aiming for, and then trying to imagine that intersection where we both have access to shared questions. It’s not, “Do it this way,” it’s, “What if…?” or, “Consider this…”

GJCynthia, were you dancing with other people and doing your own choreographing simultaneously, or was there a moment when you switched from one to the other?

COIf that was 2007, I had been doing my own work exclusively for about seven years at that point. I moved to Illinois in 2000. Prior to that, I was in Laurie Carlos’s theater company and I was dancing with Ron Brown in New York.

My history with Bebe goes way back. She’s going to hate this but I’m going to tell you a story: I auditioned for her in 1985 or ’86 and I got cut really early. I was guided to her audition by Nina Wiener, who I had taken a summer workshop with. I was really young. I was trying to figure out who I was as a dancer. Bebe, were you dancing with Nina at the time?

BMNo.

COYou were starting your own thing. Bebe was hot in New York and everybody was showing up at this audition, there were hundreds of people there. And a girlfriend of mine and I went. I got cut before she did so I was waiting outside for her and she came downstairs and told me about all that went on. We were super young. I followed Bebe’s work for years after that. I started dancing with other companies, but whenever I was in town and Bebe had a show, I would go. I was a fan for years.

Then, when I took a position at the University of Illinois, Bebe had already been teaching at Ohio State for some years. And every once in a while she would tap my shoulder and say, “Well, there’s a position over here at Ohio State that you might think about.” And one year she called me and I thought she was coming to tell me about a teaching position. Instead, she tells me, “I’m working on a new project and I wonder if you might be interested in working with me on it.” I was elated. That’s when I told her about my audition in 1985 or ’86. And she was like, “Oh God, don’t tell me.”

BMI hate those stories, because I feel like, What was I thinking?

GJWell, it worked out in the end.

BMIn the end it worked out.

I really love to watch and take stock of, not the subtext, but the subdermal of what’s happening when dancers improvise.

Bebe Miller

COIt was amazing because I’m expecting to go to this rehearsal and see the Bebe get down! And I walk into a rehearsal and the dancers are following a video of a construction tractor that they’re imitating with their arms. There was very minimal movement [laughs]. It was hilarious. It became the beginning of the process that Bebe called “Watching Watching.”

BMRight, Talvin Wilks and I were behind a television that a group of three or four dancers were watching to learn choreography; they were doing something in unison and then they’d rewind it and do it again. There was a beautiful unselfconsciousness to it. That began this whole thing of watching the watching, and eventually we even incorporated a bit of it into the performance of Necessary Beauty.

COYes, that was the start of me dancing in Necessary Beauty.

BMI really love to watch and take stock of, not the subtext, but the subdermal of what’s happening when dancers improvise. Spatially reading it in a way that perhaps the dancer is not. I feel there’s such a pleasure in working with people who are interesting and have a sense of what it is that they’re doing and what they’re creating. How do I add another dimension or facet to what’s already there? I don’t feel responsible for making it happen. I’d rather just take part in the building.

GJThat’s a beautiful way to put it.

COTo me, the thing about Bebe that’s different from anyone else I’ve ever worked with is her insistence on, and ability to sit in, that place of unknowing and still be assured that it’s going to congeal into something. It’s an ability that resides deeply in her, and it amazes me. I’ve been thinking about that a lot, about a willingness to be in the world of the unknown. A lot of times, because of the demands of the funding we have to talk about our work as if we know what it’s going to look like, but so often we really don’t know where it’s going.

BMAnd then, at a certain point, we have a sense of where we’re heading, but there’s a particular kind of leap that we can ask of each other: “Let’s go there and see what happens.”

GJIt sounds like there’s a pressure to know where you’re going, how you get there, and what happens once you arrive. And right now, to bring it to the present, is a major moment of unknowing with dance, with the world. How, if at all, has the pandemic affected the way you work?

COWell, I’ve been in a place of not knowing what the next moment is for me careerwise. I’ve had a couple of clear and distinct eras: one where I wanted to dance for other people, and then that shifted and I started to be interested in the “making.” That eventually started to slow down and I wanted to dance with other choreographers, like Bebe, or Tere O’Connor. And now I don’t feel the desire to dance in that performative way anymore. Of course I’ll get down when the music is right; it doesn’t mean I won’t dance again. But I can’t imagine wanting to do that right now.

BMBut you know what? It’s going to come for you.

COYou think?

BMYeah. It might come back as a different desire from wanting to get up in that performative way. For me, I’ve turned much more toward improvising. I even performed in March, right before the shutdown, in Rhode Island, and improvised a ten/twelve-minute piece. In it, I was learning something off a video of Darrell Jones; I was doing “Watching Watching.” There was a texture of trying to pay attention to him while I was in view of other people, and also knowing that my body can’t do what it once did. I realized, “Oh, it’s a range. I’m not going to do what he does, but at the root of it, there’s a song in his rhythm.” So could I get that? You get to give yourself a different kind of problem to solve. But there’s an exchange of vulnerability. As the audience is watching this, I’m trying to do this thing, and we’re both meeting in the middle. I think that’s about trust, and that can happen at any age. It doesn’t feel like a task to me; it’s more like an opportunity—“Here we go.” I’m curious as to how you will deal with that.

COIt’s interesting to hear you say that, because the creation of boom! came out of a moment like that. You’ve pulled me out of another moment like this before, Bebe: I’d just come out of cancer treatment and I didn’t know if I’d be able to dance again. And Bebe, you said, “Well, why don’t you try making just a little something for this Danspace [Project, New York] event?” I was mortified. I really was. But I talked it over with my partner and I said, “Well, I wouldn’t want to do a solo because I don’t know if I’m going to have the stamina. I don’t know what I can do with my body.” And so I decided that I would do a duet with Leslie Cuyjet, because she’s someone—speaking of vulnerability, Bebe—she’s someone I thought I could be in a studio with for hours on end and be vulnerable. So I decided to try it, and to build into the choreography moments where I could forget, move around, look at her, say something that betrays, “Oh shit, I don’t know what I’m doing right now” [laughter]. That’s how boom! came about.

BMI feel honored to have had any kind of place in that. It just speaks so personally and fully. There’s no doubt involved. That whole speaking section—

COWe call it “the rant.”

BMThe rant! The tone, that bit of accent—it was such a pleasure to hear that, and to feel that, and to feel the two of you there, your partnership was just really wonderful.

COSo much of it came out of play. For one, I had to write it because this cancer came out of nowhere. So boom! was a reference to that struggle. Writing that text, I started expressing that sentiment, and all the ways that cancer, and life in general, undoes your world, or what you thought was your world. Leslie and I started riffing on that.

BMThat’s so interesting because I feel the subject matter in a very different way: I feel the him you were directing this to. We understood it as a romantic relationship, but in fact it came from a different kind of physical vulnerability, of health, and it’s about a relationship between you and your body. That’s fascinating.

GJThis was in 2012, for Parallels, part of Danspace Project’s Platform series?

COThat was the first version.

BMBut that was a short version.

GJAnd then you continued to work on it. Does each iteration of boom!, particularly this most recent streaming through New York Live Arts, feel different in some way? In live dance, each time you perform a work it has a new life, physically. Revisiting something on the screen, did it take on a new life in today’s context?

COOh, for sure. I mean, I think every dancer, when they see themselves on-screen—you feel it viscerally as you’re watching. I feel my muscles sort of twitch in the places they would need to be activated in a certain section.

We did the seventeen-minute version for the Danspace Platform. It was a kind of universal set of experiences that people could relate to, so the response was overwhelming and we were asked to do it again. Later, New York Live Arts invited me to do whatever I wanted and I said, “Well, I want to keep this piece as is.” So we had a shared evening of two short works with Souleymane Badolo. Then, as we were toasting the success of the evening, the artistic director of New York Live Arts at the time, Carla Peterson, said, “Well, we’re going to commission Cynthia to turn boom! into a full-evening work.” I was surprised and honored, but I didn’t want to do that classic compositional thing of “stuffing”—opening up each section and exploring it further. I thought that it was successful in the chunk that it was and I didn’t want to fuck with that. So I posed a question to myself, which was, If that’s perfect for me as it is, where would I go from there? That’s what led to the development of what you saw in the streaming, the sections that followed. We continued the rant and made it more elaborate, and it developed into something that ended in a very long silence.

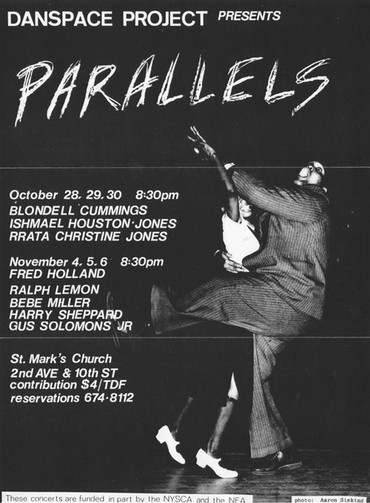

GJBebe, I’d love to hear about your curatorial perspective, and the choice to include this piece in the Danspace Platform. Maybe just to take a step back, could you give an overview of the themes that were part of that program in 2012, which itself was a revisiting of the original Parallels that took place in the ’80s, right?

BMThe original Parallels was in 1982. Ishmael [Houston-Jones] was the organizing curator. He was interested in who the Black folks were who were doing alternative dance and choreography at the time—let’s see: Ishmael, Ralph [Lemon], me, Harry Sheppard, Blondell Cummings, Rrata Christine Jones, Fred Holland, and Gus Solomons. And I think it was the first gathering of that particular group—we kind of knew of each other but we didn’t all hang out. Then, in 1987, we were asked to put together a tour. The group expanded to include other artists such as Jawole [Willa Jo Zollar]. We called it “Josephine Baker Contingent” and it went to Paris, London, and Geneva. Because of that thing that happens on tour—you’re together for a length of time, you see each other constantly, you have multiple performances, you hang out—we became friends.

I still remember we were on some street in Paris hanging out, just standing around, and the police came by and they just kind of slowed down, like, “Hmm, who are you guys?” That was 1987, so you think, “Oh, here we are again.” This is one of the things about touring, about showing your work to an audience that’s not familiar with you: you get a whole other sense of how the work works, what feels successful, what feels unexpected or not. And you’re met with the audiences’ expectations of African Americans in Europe. I remember there was a white gentleman in the audience once who was getting on Ralph’s case for not being African American enough in his work. You know, those kinds of things that, well, still happen. I was pretty quiet back then, but I just got up and said, “You can’t say that! Who are you to say that?” I just thought, “The nerve of that person.” There was such a range of work among us. I mean, Fred and Ishmael in their boots and cowboy hats had something of a western thing to it, and Ralph in a long skirt doing his Wanda in The Awkward Age. Jawole, did she have a raw egg that she broke on herself? What a great group!

To fast-forward to 2012, it wasn’t about re-creating that original moment of Parallels but just jumping off from that point and seeing what other voices were doing thirty years later.

We’re always making something about what it is that we’re thinking about, what captivates us, what torments us, what we’re in dialogue with or trying to figure out.

Cynthia Oliver

COIt’s also interesting to think that the question still circulates about Black dance or Black people creating dance. Sally Banes passed on recently, and the first time I read about you [Bebe] and Jawole might have been in an essay of hers that categorized you both, and others I knew at the time, as doing kind of “identity dances.” Well, why are certain artists labeled “identity-dance makers” and others are not? Are people who are not Indigenous, people of color, not considered to be making dances that say something about their identity every time they create something? Essentially, we’re all always doing that. We’re always making something about what it is that we’re thinking about, what captivates us, what torments us, what we’re in dialogue with or trying to figure out. For me, choreography is about trying to figure shit out. Can I figure it out physically in space and time? And to think that because the material was unfamiliar it was somehow an “identity dance” was really irritating.

I suspect there are sectors of the population that still think there’s a standardized “Black dance” that comes out of an [Alvin] Ailey-esque tradition. There are people of color across the globe who are doing dances that divert from that. So it’s interesting that was anointed “Black dance,” and if people were doing something different, they were traitors to the race, and they had to take a stand to say, “I’m an artist first before you label my dancing.” I know that was irritating for a while because people felt like, “No, we need more people who are claiming the identity.” But I also know that you want the work to be considered without having to carry that burden all the time. I’m proud of Black culture, I love it, I love it everywhere I see it. But it’s interesting how those kinds of limitations are imposed.

BMI was thinking about this idea: for a while, the telling of the Black experience was just considered a particular part of the Black experience. But there’s no separating myself from the Black experience, regardless of whether anyone else has had the same experience that I have. I think there’s still a bit of surprise at the range of how the world can be seen. Choreographically, I find myself moving away from demonstrating a particular, fixed point of view. Rather than being the point of view, I get to go forward with the view that I happen to have in front of me.

And Cynthia, it’s been three and a half years now since I stopped teaching at Ohio State. And I wonder, what do you find with students up and coming? Is that story of Black identity in dance still being fleshed out, or trying to be claimed? Or are we more familiar, in a sort of Afrofuturism way, with just saying, “This is where I am—I don’t need to bring you along if you don’t get it. This is what it is.”

COI wish I could say that were the case, but because so much of the design of the curriculum in institutions is descended from a Eurocentric point of view, every step of the way has to be questioned. Because of tenure also, those traditions are still dyed in the wool. They’re in the fabric of every program. So looking at difference ends up being an elective, an add-on to the program as opposed to the core of it. Trying to figure out how to fundamentally change something that has historically been anchored in Eurocentrism is a really tall task.

GJRight now, when dance isn’t happening on stages but on screens, with streaming, such as with boom!, and in streets, with Black Lives Matter protests and demonstrations, I’m curious to hear any thoughts you have about dance and its community in this moment.

BMEven at my age, I feel there’s time to take in this very particular moment, physically, where we’re in small rooms. I’m watching the pacing of masked faces and the way we signal each other now: there’s a kind of choreography in the pandemic. And there’s time to take this in. It’s disrupting our regular sense of how work is made and produced and performed, but I don’t feel that we’ve left live performance behind at all; there are pockets of that appearing online and on the street. But there’s a physical humanity that we’re all witnessing.

COI’m fascinated, too, by the everyman who now has to choreograph every time they go out in the street. I’m constantly observing the movement choices people make—I’ll think, Let me take charge of this and design how we negotiate each other because you are clearly confused [laughter]. And maybe we can use this moment to choreograph very different relational experiences with one another, in an effort to fix what’s broken.