Catherine Taft is a curator, writer, and deputy director of the Los Angeles–based nonprofit LAXART. She is a regular contributor to Artforum magazine and teaches in the Graduate Art Department at ArtCenter College of Design. Taft is currently working on an exhibition and publication examining four decades of ecofeminist art, for which she received a fellowship from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

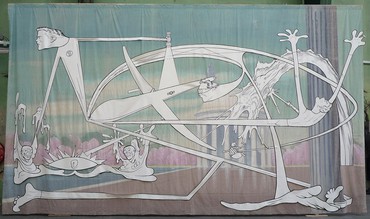

With originality and timeliness, Jim Shaw captures the American psyche in his layered and dexterous art. His paintings, drawings, videos, and installations synthesize cultural ephemera floating in the air, from hot-button current events to arcane historical obscurities and the individuals attached to them: cult religion, midcentury advertising, military operations, catastrophic weather events, cartoons, partisan figureheads, and those who really pull the strings. Employing precise draftsmanship, Shaw approaches his subjects with curiosity and aplomb; he wields art historical styles—like photorealism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, and comic illustration—as they serve the needs of his overarching narratives, giving layers of meaning to the works’ assorted symbols. His mural The Jefferson Memorial (2013), for example, borrows the Cubist composition of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937) to present four comic-book superheroes with the power to stretch (Plastic Man, Mister Fantastic, Elastic Lad, and Metamorpho), their bodies forming vaguely Googie-style architectures (think of the iconic 1961 Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport). Painted on a found backdrop depicting a domed classical building, the weird men hover over the ground, attempting to hold back a US military drone with their protracted limbs and torsos. It’s an epic scene of good versus evil, absurdist and eerily all-American.

Describing The Jefferson Memorial in Artforum, Shaw stated, “Much of my recent work also relates to nineteenth-century political cartoons, and I figure that the drones and their equivalence to Nazi aerial bombardment are a fit subject for dark political humor in the present decline.”1 Indeed, one may point to the “present decline” of American democracy, global ecology, or sustainable economies as fitting jumping-off points for straightforward political satire. However, Shaw, with his visionary appropriation and skilled recombination, moves beyond satire alone toward something darker and more baroque. He uses decidedly twentieth-century daemons in the service of new, mercurial allegories, and as the last century slips further into memory, these characters begin to embody human nature’s profound failure to evolve. His vision is one of an American limbo, troubled waters into which the artist wades deeper and deeper.

A body of work from 2020 is perhaps Shaw’s most politically inflected to date and reveals just why American culture, politics, religiosity, and consumerism are so ripe for the picking. Take, for example, the black-and-white painting Donald and Melania Trump descending the escalator into the 9th circle of hell reserved for traitors frozen in a sea of ice (2020). As the title describes, Shaw envisions the former president and his wife on a quasi-conveyor-belt ride into one of the four frozen lakes of the ninth circle of hell as conceived by the medieval Florentine poet Dante Alighieri. In Inferno, the first part of his epic allegorical poem The Divine Comedy, completed around 1320, Dante describes Antenora, an area of the frosty Lake Cocytus where traitors are punished, their bodies trapped in ice with only their heads protruding. Shaw depicts these wretched creatures as former Trump aides and other political villains; behind them, Satan lurks as a dark-winged, three-mirrored vanity (a chest of drawers, that is), the ultimate creature of self-absorption, conceit, and deceit. Are we to believe that Donald and Melania have also been sentenced to an eternity in the frozen lake? Or perhaps they are venturing downward to survey the many traitors who were unfaithful to the Trump agenda, the countless staffers who resigned during his administration?

The forty-fifth president appears again in The Master Mason (2020), a large acrylic work painted on a section of found muslin backdrop. Here, the smirking politician is dressed as a founding father—namely George Washington—complete with tricorne hat and Masonic ritual apron, an emblem of innocence, righteousness, and proper conduct. The all-seeing Eye of God (like that from the almighty dollar) hovers above the scene like a triangular UFO that recalls the alien invaders of War of the Worlds. Trump, too, towers above a throng of followers, also in colonial dress, and some of whom resemble actual members of the president’s cabinet—Jeff Sessions, Kellyanne Conway, and Steve Bannon—though it hardly matters that they’re based on historical figures. They form an honorific chorus of devotees, presenting the severed heads of the Master Mason’s enemies. Alongside Donald and Melania Trump descending the escalator into the 9th circle of hell reserved for traitors frozen in a sea of ice, Shaw presents a portrait of the maligned leader with his believers and deceivers, and a parable of twenty-first-century despotism.

[Shaw’s] vision is one of an American limbo, troubled waters into which the artist wades deeper and deeper.

Political figures and historical emblems seem to offer Shaw barometers for charting the progress (and decline) of American democratic ideals—and often those factual emblems are outlandishly unbelievable. His 2022 painting The Bay of Pigs Thing is based on an image from the 1960s that stuck with the artist for its questionable content, a swimsuit editorial in which models frolic on a beach alongside a group of marines simulating the Normandy landings of World War II. This original source would read as tone-deaf today, yet incorporated into Shaw’s allegorical composition—a visually riveting scene of the Watergate Complex bursting forth like some biblical flood—these figures are redeployed to exaggerated, dreamlike ends. Here, midcentury pop culture and Castro/Kennedy-era conspiracy theory mix to further embody a familiar strangeness that can only be described as the mood of our present-day, QAnon alternate realities. Here, as in so many of his works, Shaw takes political references beyond satire and critique to stage full-on history painting, presenting an ambitious narrative that mirrors the past to reflect on the present.

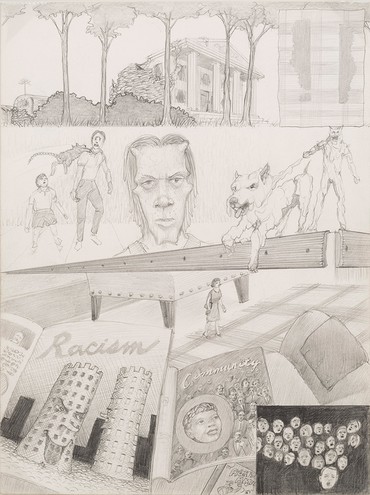

In his dizzying style of history painting, Shaw confidently remixes the fragments of high and low culture that surround him. He looks backward in time—at Dante, Walt Disney, the Book of Mormon, vintage comics, Leonardo, William Blake, Richard Wagner, Freemasonry, et cetera—to chart the course of American empire and free-associate with its terror. In many ways, Shaw’s politically inflected work recalls his earlier Dream Drawings series (1992–99), for which he documented his dream symbology as a propagative function for his art. Literally drawn from his unconscious, these graphite-on-paper works generated a rich visual rhythm that laid a foundation for his later, more intentional compositions. Shaw’s recent political pictures capture the compositional originality, free flow, and social imagination of the Dream Drawings, but with a deeper, sometimes barbed significance. As Shaw described in a 2020 interview:

I had become interested in the tropes of political cartooning, which I felt used the same kinds of visual punning I was finding inherent in my dreams as I drew them out, so I was eager to put that to work. Then a couple of things happened. My wife, Marnie Weber, needed a backdrop for one of her films, and we found it was cheaper to buy a worn out used one than to rent a newer one, and as I looked at what was for sale, the pieces that were set in an Americana mythological past attracted my mind. It was during the ramping up to the second Gulf war, and I wanted to explore the ways that Bush Jr was using the Reagan-esque nostalgia for a glorious past that existed, in reality, thanks to FDR and the new deal, and all that socialism they were trying to bury. So, I began with full scale backdrops, and I thought the scale was appropriate to political cartoons.2

By turning to old theater and cinema backdrops for his painting supports, Shaw radically scaled up his two-dimensional work while indulging his voracious collector’s appetite and seasoned eye for marginalia and rarities. The artist may admit to being something of a recovering packrat, and certainly his Thrift Store Paintings—his 1990s conceptual project of collecting, exhibiting, and even forging found amateur paintings3 —points to this predilection. Shaw’s sourcing and reuse of muslin backdrops might well be a material evolution of the impulses behind his Thrift Store Paintings series; even if the weathered backdrops are rendered in a more professional, industry hand than the earlier found canvases, Shaw locates within them a similar index of vernacular American tastes, mutating values, and worn-out fantasy ideals (aka “movie magic”).

Take, for example, the monumental painting Untitled (U.S. Presidents) (2006), a sixteen-foot-tall by thirty-eight-foot-long rendition of the American flag. Instead of stars, there are forty-two disembodied faces of former presidents, from George Washington to George W. Bush, an array of whiteness from the beyond.4 In place of stripes are seven blood-red corn snakes stacked horizontally, mouths, snouts, or tails pointed ferociously toward the viewer. These elements hover over a found backdrop depicting a typical small-town American street, including a white picket fence, modest houses with white siding, and a row of bare trees. As a finishing touch, a doughy, larger-than-life donut is rendered smack in the center of the picturesque scene. From president to predatorial snake, wholesome hometown to deep-fried confection, Shaw composes a portrait of the saccharine and the profane. It’s an embrace of a make-believe American politeness (or Puritanism) that gets flattened by its slithery opposite, the systemic malevolence of a bigger, more sinister complex.

1Jim Shaw, statement, Artforum 52, no. 10 (Summer 2014), available online at https://www.artforum.com/print/201406/jim-shaw-46877.

2Shaw in Alexander Harris, “Contemporary Painters Artist Interview: Jim Shaw,” Lund Humphries, August 5, 2020,

https://www.lundhumphries.com/blogs.

3Forged amateur paintings were shown as Oist found thrift store paintings and were never shown together with real thrift store paintings. [Editor’s note: Shaw’s ongoing project Oism, which he initiated in the late 1990s, is an artistic attempt to create and promote a functioning religion, complete with its own history and symbolism, rituals and traditions.]

Artwork © Jim Shaw