Wyatt Allgeier is a writer and an editor for Gagosian Quarterly. He lives and works in New York City.

Lia Robinson is a curator specializing in global modern and contemporary art. She currently serves as director of programs and research at the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation, which is committed to presenting and preserving the legacy of the video pioneer Shigeko Kubota (1937–2015) and to supporting research, experimentation, and broader access to artistic practices at the intersection of art and technology.

Lumi Tan is a curator and writer based in New York. She is currently the curatorial director of Luna Luna, a traveling art amusement park that originated in a 1987 project conceived by André Heller. She was previously senior curator at The Kitchen, New York, where she organized exhibitions and produced performances with artists. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Artforum, Frieze, Mousse, Cura, and many exhibition catalogues. She was the recipient of the 2020 via Art Fund Curatorial Fellowship.

Wyatt AllgeierLumi, let’s start at the beginning. How did this exhibition come about?

Lumi TanOne of my first curatorial projects at The Kitchen was an archival exhibition marking the institution’s fortieth anniversary, in 2011, which I curated with the executive director at the time, Debra Singer, and curator Matthew Lyons. The exhibition, The View from the Volcano, covered the The Kitchen’s SoHo years, from 1971 to 1984, before our move to our present building in Chelsea, which is currently under renovation. It allowed me to spend invaluable time in our archival holdings and rooted me in our history from the beginning of my tenure.

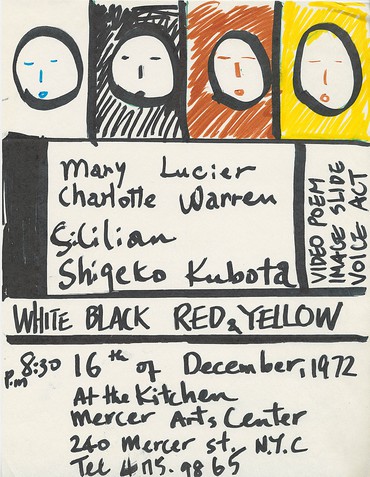

It was during this research that I first learned about Red, White, Yellow, and Black, when I came across The Kitchen’s striking poster of these four women, styled like mugshots, from the first performance. I was surprised that The Kitchen didn’t have much more than that poster in its archives, but just from seeing the poster, and the boldness of the name these women had chosen, the performances implanted themselves in my mind as something to research further. It wasn’t until we were approaching The Kitchen’s fiftieth anniversary, in 2021, that I was able to delve deeper into this history. That’s when I first contacted the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation and met Norman Ballard, Reid Ballard, and you, Lia, who have made all of this possible.

Lia RobinsonThis project resulted from close collaboration with the remaining members of Red, White, Yellow, and Black—Mary Lucier, Cecilia Sandoval, and Charlotte Warren—along with The Kitchen and the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation. I am very interested in transnational artist networks, especially artists working between Japan and the United States at the intersection of art and technology, which brought me to Kubota’s work as part of Fluxus and other avant-garde experimentation in the 1960s and ’70s. I was really fascinated by her underexamined performance-based work and visited The Kitchen archives while still a student. That’s where I initially came across that Red, White, Yellow, and Black poster. The concerts were already sort of apocryphal among feminist scholarly circles, there was so little known about them.

That first encounter in the archive piqued my interest and I always hoped to return to the coalition, so when Lumi came to visit Kubota’s archive to propose this project, in 2019, it was really exciting to start mining the archive. We uncovered correspondence and planning materials in Kubota’s personal collections and began a dialogue with Mary, Charlotte, and Cecilia to get a fuller sense of their experiences at The Kitchen and their performances as part of Red, White, Yellow, and Black.

LTThe research project started with Kubota’s crucial yet underknown presence at The Kitchen throughout her career, as a contributor to the early Women’s Video festivals there [in 1972–74] before she became a video curator at Anthology Film Archive, and then having a number of important solo shows throughout the years there. I had also previously worked with Mary on an installation for the group exhibition From Minimalism into Algorithm at The Kitchen in 2016. Knowing that she was also a member of Red, White, Yellow, and Black—and that, in addition to exhibiting her work at The Kitchen in the 1970s, she also played an integral part in archiving The Kitchen during many other artists’ presentations over the years, both as a photographer and just generally as a member of The Kitchen’s community—it became clear that we could build a substantial project around Red, White, Yellow, and Black.

WALia, could you say a bit more about what your day-to-day is like? I’m curious to hear about the work going on in the archives.

LRWell, the mission of the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation is to preserve Kubota’s legacy as an artist, curator, and critic in addition to her collaborations with contemporary pioneers. Although it’s one of many facets of the foundation’s activities, archiving Kubota’s personal collection is central to uncovering these stories. There has been a renewed interest in her work in recent years, and the focus has been on restoring her work to make it accessible to the public and to researchers. Archiving is ongoing parallel to our exhibition and program planning, and on any given day in the archive we come across a range of artwork and materials, from Flux objects, video sculptures, open reels, recordings, and materials for programs at Anthology Film Archives to the artist’s journals and correspondence, including that between members of Red, White, Yellow, and Black. Our day-to-day is a mix of archival work, research, and restoration, and at this point about two-thirds of her personal archive is catalogued.

One of the most exciting projects is my colleague Reid Ballard’s work cataloging and digitizing Kubota’s open-reel and tape collection, which will make hundreds of new materials available for viewing for the first time in decades. Just recently we came across Kubota’s Analogue Magnetism for Takehisa Kosugi, shown, to my knowledge only once, at The Kitchen , in the 2nd International Computer Art Festival in 1974. Throughout the process we have found that Kubota and other women in the avant-garde scene at the time were their own best advocates and archivists, actively preserving their own histories in a consciously forward-thinking way. They serve as a model for how artists can continue to think about how they want their work stewarded in the future.

LTIt’s similar to The Kitchen: from the very beginning, it started from the place of, No one else is going to tell our history. The work we’re showing, the artists we’re supporting, are never going to be folded into the canons of art history, so it’s necessary to record it all, and to remember it all ourselves. Being a place focused on ephemeral artwork such as performance and video, we quickly developed a habit of saving as much paper as we could, and documenting via video and photography as much as we could. Of course, many of the artists in The Kitchen’s orbit are now collected in museums and included in art-history books, but The Kitchen’s ability to document as a center for video was a rare resource in those early decades.

LRHaving said that, with the exception of Mary preserving her scripts and slides and Shigeko preserving her tapes, the material for the seven works that constituted Red, White, Yellow, and Black was not extant. The women all used Kitchen equipment that was then repurposed for other events and performances. So it wasn’t necessarily a moment when they were thinking about preserving any physical hardware or objects associated with the works. I think when people think about these types of performance-based works and multimedia video sculpture, they forget that The Kitchen was truly an experimental space where most everything was considered, in a sense, a work in progress. The members of Red, White, Yellow, and Black were exploring a number of new ideas—about art, technology, and identity—and many of the audience members were other artists and collaborators. They were very much developing their work as part of a dialogue with each other and The Kitchen community.

Another aspect of the events to keep in mind that became clear during the oral histories with Mary, Cecilia, and Charlotte in preparation for the exhibition is that all four artists were presenting their work in parallel to one another, all at once. It wasn’t a formal, linear presentation that went from artist to artist; rather, the audience had flexibility to move through the space and experience the works simultaneously. These weren’t static, and the experience must have been greatly impacted by the actions of the audience.

We do know that for the first concert Kubota made a video sculpture that seems to have been thirteen monitors of six channels. Five channels featured footage of rivers pulled from her diaristic practice during her travels across Europe. From what we’ve gleaned from preparatory notes prior to the event, each channel was shown on a horizontal stack of two monitors accompanied by an audio recording with excerpts from James Joyce’s reading of Finnegans Wake. Another stack of three monitors displayed a closed-circuit video of a drinking fountain filled with orange juice. There was a live synthesizer altering the images of audience members who could take and drink orange juice from the fountain. It was an interactive piece that invited audience participation.

LTWhile this was happening, Mary performed Red Herring Journal: The Boston Strangler Was a Woman. As she clicked through slide projections of photos of female criminals, she read descriptions taken from articles about female criminal biology: “She had a deep voice, she was believed to be a lesbian, she was beautiful,” et cetera. As part of the performance, Mary was getting progressively more drunk, or at least portraying herself as such—taking on the role of what a “bad woman” was assumed to be. The concept was spurred by media coverage related to Albert DeSalvo, the “Boston Strangler,” who murdered thirteen women in the 1960s, when Mary was an undergraduate at Brandeis University in Boston. The media speculated that the Boston Strangler must have been a woman, or perhaps dressed as a woman, because otherwise why would so many women let a strange man into their homes?

Then for that first performance Cecilia was supposed to call in on the telephone—she was with her family on the Navajo reservation in Chinle, Arizona, not on site at The Kitchen. But the performance never happened; her call was interrupted because of bad weather.

LRBut we did learn in our oral history with her that she was going to perform the song “Mary Had a Little Lamb” in Navajo, alluding to her liminal identity as half Navajo and half Caucasian. Her family had given her a nickname, which translated to “little spotted lamb,” because she presented as more Caucasian than the rest of her family. Cecilia was still grappling with her identity and place community when she went abroad to be educated in France, performed in Red, White, Yellow, and Black, and went on to have an impressive career in the US military.

LTAnd in Black Voices, Charlotte performed a combination of a live poetry reading and recordings of poems by Black poets Jackie Earley, Mari Evans, Nikki Giovanni, and Langston Hughes.

WAWere each of the four artists coming to the table and presenting a concept that they had determined ahead of time, or were these works conceived in unison as a collective and workshopped together?

LTWe’ve learned from the oral histories that as far as they remember, there was very little discussion beforehand as to what any of them were going to do. It was all quite casual, in the spirit of the times and the artistic scenes they were traveling in. This wasn’t a collective in that sense of workshopping; it was more of an affinity group that meant to highlight individual approaches and practices within a group. That’s a critical aspect to keep in mind when thinking about this as a multiracial coalition: it was never about “I’m representing this,” it was about complicating expectations, depictions, and approaches about how one performs oneself.

LRRight. It was really about creating a platform that celebrated this multiplicity and these individual practices. Highlighting the specific cultural context of each performer’s background, however, as well as the various impediments and obstacles that each of them had to overcome, was not necessarily the focus of the works presented. This is important to keep in mind, when nowadays there is sometimes a tendency to develop one converging narrative of a single feminism or category of feminist art in the United States and give the impression of speaking to all women’s experiences. These concerts provide a really interesting counterpoint to that: the artists were very conscious and particular about presenting multiple perspectives on an equal playing field. While they weren’t necessarily thinking about these works as forming a single narrative, their experiments remained in conversation with one another, they kept discussing the concepts and their ideas both before and after the performances. This created a system and a platform of support for each individual project and nurtured further experimentation.

WAIn addition to the oral histories that you’ve done with the artists, have you also been able to find people that were there as audience members?

LRIt’s been a huge challenge.

LTIt really speaks to the nature of what The Kitchen was at the time. These days we might have all sorts of records as to who attended performances, but back then it just wasn’t documented. People flowed in and out, and there weren’t tickets receipts or guest lists. But one fantastic piece of evidence that we found from the evening was brought to my attention by Tyler Maxin from Electronic Arts Intermix: a transcript of a phone call from the musician Phil Harmonic (Kenneth Werner) on the night of the first performance, published in Werner’s magazine A New Look. He called in to wish everyone happy Beethoven’s birthday and the phone was passed around to Mary, Shigeko, Charlotte, and also Alvin Lucier, Nam June Paik, and Elsa Tambellini. It’s one of the only documents of the evening and was completely unexpected.

LRIt also speaks to the casual setting and the fluidity and lack of rigidity in the performances themselves: Mary’s taking a break from her own performance to come tell Phil Harmonic what she’s doing, and Charlotte also takes a break from her work to say hello. And I think there’s even a point where Phil Harmonic has to hang up and then call back because Shigeko’s too busy to talk to him at that point because she’s working on setting up her Riverrun piece.

WACould you say more about what the exhibition will comprise, given that these performances, and the materials involved in their staging, for the most part no longer exist? It’s a challenging exhibition to stage, I have to imagine.

LTIt is very challenging when most of the work doesn’t exist—nor was it meant to exist after the initial run. But it’s a familiar challenge: The Kitchen has always been a place for ephemeral work, yet we have this rich archive to mine, so we have to apply a lot of ingenuity in thinking through how to bring these incomplete portrayals to life. The posthumous projects we presented of Gretchen Bender [2013] and Julius Eastman [2015] always come to mind as reflecting the complexity of what was able to be preserved of their work. So while what we’re mostly showing in this exhibition is ephemera, we’re not trying to present it all as evidence of two events. Instead, we want to prioritize the relationships between these women and what was able to be shared between their radically different backgrounds. These performances were not the beginning or the end of their friendship—even if there weren’t any further Red, White, Yellow, and Black performances after The Kitchen, they continued to correspond and to collaborate in less official capacities.

WAWhat do you hope visitors to the exhibition walk away with, be it philosophically, conceptually, or emotionally?

LRI’d hope that people come away with greater context for each individual within the coalition and her practices, and to understand her contributions to early avant-garde experimentation on a more level playing field. While Mary and Shigeko initiated the performances in many ways, I think all the members of Red, White, Yellow, and Black felt like true collaborators and equal contributors. They were deeply committed to creating a platform to promote greater visibility for each other’s practices. And the engagement and the feedback that they received, especially from other women who had similarly experimental practices at the time, was very inspiring. That’s something I hope will be really interesting for audiences now: these women maintained relationships, both personal friendships and professional collaborations, throughout the rest of their careers. Lucier and Kubota showed together multiple times, Kubota programmed some of Charlotte Warren’s later work at PS1 as a curator at Anthology, and after this collaboration, Cecilia Sandoval was featured, I believe, in Nam June Paik’s Global Groove [1973]. Red, White, Yellow, and Black is an incredible example from The Kitchen’s herstory of an artists’ model of support and collaboration that is still relevant today.

LTOn The Kitchen side, we are constantly reshaping this story of how we fostered avant-garde and experimental practices throughout this past half century. This coalition coming together so early in The Kitchen’s history, when the downtown scene was overwhelmingly white and male, is a necessary expansion of those dominant 1970s SoHo narratives. For Shigeko and Mary, much of the conversation about forming Red, White, Yellow, and Black came from being the “girlfriends” on tour with Sonic Arts Union and creating their own opportunities to headline and experiment on stage. These performances have a mythic quality because they seem to be an anomaly. This exhibition is an opportunity to continue to broaden and develop institutional and cultural history, and to cultivate intergenerational exchange in a manner distinct to The Kitchen and its legacy.

Red, White, Yellow, and Black: 1972–73 will be on view March 7–April 29, 2023 at The Kitchen at Westbeth: 163B Bank Street, New York