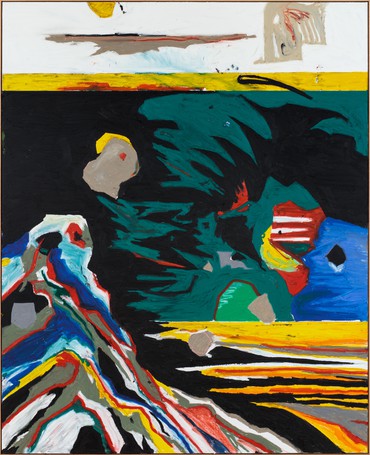

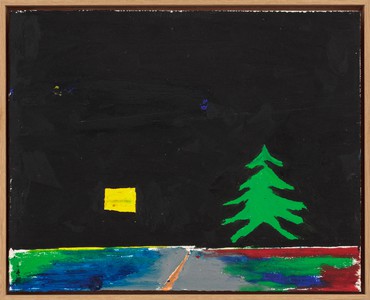

Harold Ancart was born in Brussels in 1980 and lives and works in New York. His paintings, sculptures, and installations explore our experience of natural landscapes and built environments. These works allude to a range of art historical sources and are often characterized by abstract passages of color. Focusing on recognizable subjects, Ancart isolates moments of poetry in everyday surroundings.

Andrew Winer is the author of the novels The Marriage Artist (2010) and The Color Midnight Made (2002). He writes and lectures on art, philosophy, and literature. A recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in fiction, he is presently completing a novel and a book on the contemporary relevance of Friedrich Nietzsche’s central philosophical idea, the affirmation of life.

Andrew WinerToo bad we aren’t conducting this interview on a road trip, Harold. I love the travel accounts that you’ve published—they’re so honest and intimate that they turn the reader into your traveling companion. We just met, but I already feel like we’ve logged all these hours in some tetchy and choleric Chevrolet Blazer from the ’90s.

Harold AncartNo, a GMC Yukon!

AWOh yeah, that’s what it was. I was hoping the gallery would say you were waiting to meet me in some town like Joseph, Oregon.

HAI wish!

AWRight? I’d throw the easy questions at you first, on our way over to, what, Ely, Nevada?

HAOr we’d just look out at the desert.

AWThen, pulling into Hanksville, you know, down in Utah, we’d cover painting and drawing.

HAThen you’d hit me with the heavy stuff—

AWRight, about Existence and Being—when we’re heading up into Colorado’s Western Slope. We’d grab dinner at Natalia’s 1912 in Silverton. Of course, that would probably be too prescriptive for us! Sometimes, I feel most free when I can tap into a way of being and working that isn’t governed by goals. It reminds me of what E. M. Forster asked: “How can I know what I think until I see what I say?” Does that speak to your experience of making a painting—to how much you know of what you want to do with a particular painting?

HAYeah, I do not know anything in advance. I am relatively young, but I have learned, often the hard way, that I was lucky not to have reached the goals that I used to fixate on or set for myself when I was a young adult. It is not out of many successes that I am who I am. Rather, it is in spite of anything else, and through an innumerable amount of failures. I used to have a lot of opinions and a lot of prescriptive ideas about how life should be lived and about how painting should be done or what it should eventually look like. Those were difficult times of emotional conflict and physical and financial struggle. I remember being angry that things were not going my way.

AWMy friends joke that I always say this, but you sound like Nietzsche! He wondered whether he had reason to be grateful for his failures and felt obligated to the hardest years of his life. He also cautioned against striving for a particular outcome, and even sort of mocked envisioning a “purpose” or a “wish.”

HAYes, and luckily, as a result of these inner conflicts, I have come to realize that life, just like painting, has very little to do with what I thought I wanted. I came to realize that painting was about what I was doing, and subsequently about the observations of what had been done. This said, I always have some kind of an idea of where I want to go prior to starting a painting.

AWAh, so you do have an idea . . .

HABut I tend to keep it simple: it can be an image, a shape, or the color blue. I know now, however, that these ideas, these things that the mind projects, are not to be fulfilled and that a particular destination is not to be reached. I guess that, just like Forster, I firmly believe that if one knew what they were going to paint before they actually painted it, painting would be of no interest at all. Same goes with writing or living, I would guess? Isn’t it by getting lost in writing them down that our ideas or our stories unfold? Almost as if our personal adventures, the account of a day, only begin when we start telling them or putting them into words.

AWI want to get lost in both the experience and my accounting of it. But by getting lost I paradoxically mean being present. Or maybe it isn’t a paradox, since being lost forces us to be very awake, doesn’t it? Awake to whatever will unfold.

HAI agree, and while painting, I try as much as I can to welcome the unexpected. To consider failures, if not as blessings, then at least as opportunities for change or growth. I can then watch the painting unfold in front of me while making it. Working in that spirit allows the paint to become what the paint truly tends toward (not where I want it to go). Because of this, it is very rare that I find myself conflicted after completing a painting. One can only do what one does, after all. It is in that spirit that I also try to live my life, with a vague idea of where I want to go, abandoning myself to it, watching it unfold in front of me as I walk through it.

AWCan you please be my life coach on the side?

HABelieve me, you wouldn’t want that.

AWBut it’s very beautiful, what you’re saying, because you’re talking about something rare, I think, which is achieving a kind of freedom.

HAIt’s one of the things that art—visual art, at least, when it’s good—presents us with.

AWExactly, and to connect it back to conflicts and difficulties: I feel that one of the things that makes your paintings so generous is that they seem, in part, to be a record of your struggles. I sense that some sort of acquiescence has usually occurred during their making.

HAWhat do you mean?

AWWell, as in the work of Clyfford Still, for example, there’s often a sort of jagged beauty to your paintings: you see it in the edges, but also in the worked areas of color. Yet it seems to me that you get out just before the point where they’re overworked. What’s often left are traces of dissonance. My late friend, the poet Adam Zagajewski, wrote that “one must think against oneself, otherwise one is not free.” Your paintings do give off a glow of freedom, yet they contain these frictions, and are made with these hard things—oil sticks—that are composed of thick, half-dry paint. And as with writing, as with any art form, the medium pushes back—pushes back against your freedom. It makes me wonder if, in addition to a kind of freedom when you’re painting, you also experience anxiety. Or even panic.

HAThe only moment I feel anxious is when I pace the floor in the studio, smoking way too many cigarettes instead of working.

AWI feel anxious when I’m doing anything instead of working!

HAFor me, this usually happens when I am about to start a new work and the canvas is still untouched and I am thinking about it too much. As if there was a risk that I would fuck it up . . . there is no way one can fuck anything up beforehand . . . perhaps the anxiety is because, beforehand, the realm of possibilities is vaster than it is once you have already started?

AWYes!

HAI don’t know. It’s a bit like jumping into a lake on a hot summer day. If you try to enter the cold water gradually, you may take forever to enter. You must plunge into it, one way or another. Headfirst or not makes no difference—once you’re in it, you ultimately feel good. I call it “the zone.” A lot of things happen in there . . . some of them I will probably never be able to describe. But if there is one thing that doesn’t belong there, it is anxiety or self-esteem issues. There is struggle of course. I would even say that struggle is the necessary condition around which everything is built.

AWLife coach. I’m telling you . . .

HAAnd I’m telling you . . .

AWTell me more about “the zone.”

HAIt’s a zone of tension. That tension resides between two things: what the mind demands is one of them, and what the hand can do is another. It happens all the time that the mind rejects what the hand has done. This is where I find freedom.

AWInteresting. So, freedom isn’t a willed thing—

HANo, it’s when something unexpected happens. When a terrible choice has been made or when something happens to be poorly executed. When it doesn’t look like how it usually does or when it doesn’t look how I think it should look. When one starts thinking against oneself, as Zagajewski says. The fact that you can only do what you do doesn’t exclude ending up doing something you usually wouldn’t.

painting has to do with both the ability to dream of an elsewhere and the capacity to distill elements of the everyday visual environment.

Harold Ancart

AWThat’s brilliant. And comforting, somehow. Do you think that, in this way, art can lead us to our longings?

HAI don’t know how to answer that question. As a young child, I was never satisfied with the here and the now. I have always had a tendency to create some sort of alternate realm in which I was the almighty sovereign. Every child does that to a certain extent, I suppose? And that’s fine. Except that I am no longer a child, and it hasn’t changed much.

AWFor you, and for many adults.

HAOne must dream. I think it’s essential, but to what extent? I suffer from escapism. Pathologically. Sometimes I wonder if longing is actually a good thing . . . being here and wishing to be elsewhere. To ultimately realize, over and over again, that there is no there there, and that reality belongs here and now. That’s brutal. The human condition is brutal. I do not see how one could live if one didn’t have the ability to escape into one’s own thoughts. But, to return to reality, this cruel reality with its physical rules and needs . . . it’s like trying to eat soup with a fork.

AWThat’s what I was trying to ask before: should painting show us a world equal to our longings? Or should it change our longings? What I mean is, we often say that someone who dreams of the world being different from what it is—as in John Lennon’s “Imagine” or Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream”—is a person with imagination. Those are attempts, you might say, to impose what’s imagined on the world—in order to change it. Do you think there are painters like this? There’s also another kind of dreamer, who lets the world reveal and form itself around them, the kind of dreamer who is capable of becoming enchanted with whatever appears. Do you identify with one of these kinds of dreamers?

HAI certainly do relate to both—to the first kind of dreamer, whose dreaming is so strong and persistent that it ends up altering their surroundings, and to the second kind, who finds enchanting moments in the ordinary. For me, they go hand in hand. The dream of a better life became true when I came to realize that everything is and always has been there, lingering, waiting for me to finally be able to see it. I personally believe that painting has to do with both the ability to dream of an elsewhere and the capacity to distill, or isolate and extract, elements of the everyday visual environment. These are the things that dreams are made of. This ability to recombine or to reframe allows you to give shape to an elsewhere, whether it is a human figure or a cloud, a window ledge or an abstraction.

AWWhat you say about painting—that it has to do with both the ability to dream of an elsewhere and the capacity to distill elements of the everyday—returns me to the Monet–Mitchell exhibition I just saw in Paris, and makes me think of the late Monets in particular, which have that quality without question, but which, stripped of their frames, also confront us with something shocking: their provisional nature. You can feel the speed with which Monet’s arm and wrist moved across the canvas, how fast and extemporaneously those paintings were made. After all, he was trying, in each of them, to capture the light of a particular part of the day—before it changed. I happened to be there, at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, with the painter David Salle; it was late, and we had only an hour before closing on a rainy cold night, so almost no one else was there, and we were able to move around the paintings as we pleased. I learned then that Salle is a fast looker: we did that place in forty minutes, and this, too, added to my sense that when it comes to making art, whether with paint or words, there is so little time. What’s that passage from the final volume of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, where he writes that the mind has its landscapes, and almost no time is permitted for their contemplation? Proust tells us that his whole life has been equivalent to something like a painter hiking up a road over a lake that he wants to paint and that’s obstructed by rocks and trees. Brushes in hand, he can glimpse the lake through the gaps, but night is falling, and he will soon have to stop painting, knowing that no day will ever break again. The Monets haunted me. But I couldn’t understand why until speaking with you now. It seems like we have so little to go by, that the whole enterprise is doubtful. Adam [Zagajewski] was referring to this, I think, when he wrote that doubt is more intelligent than poetry, but that poetry surpasses doubt. In other words, we can’t get rid of doubt, and it can even be good for our art, but we need to trust that art, executed properly, overcomes doubt. Do you ever feel, when painting, that you’re answering to this kind of “I don’t know,” or managing it, say, with technique?

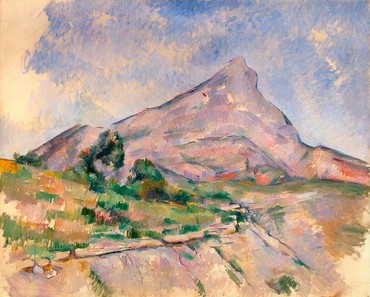

HAWell, this is why I can say that, when it comes to my paintings, subject matter doesn’t hold as much significance as you might think. If I choose to make a painting that pictures flowers, for example, it pictures flowers almost in spite of all the meanings that we attach to flowers. The flowers in this case serve as some kind of alibi that allows me to push color onto the canvas. I do not see myself as a painter of images. I see myself as a painter of color. When I think of all the figurative painters that I admire (the list is long, spanning from Monet to Cezanne, or van Gogh to Picasso or Matisse or Guston or Thiebaud, to name a few), I also think about them as painters of color. It becomes more evident with the abstract painters that I like, such as Newman or Still or Diebenkorn (although he sits somewhere in between), that they are painters of color. I don’t know whether all these figurative painters were particularly attached to the images they were painting, but to me it feels secondary. The subject feels secondary. When you look at van Gogh, who is the opposite of Seurat, it seems evident that very little is scripted or predetermined. He is guided by some kind of a flux that allows him to open a door to somewhere that is beyond the subject of the painting itself, and this beyond is a place that even he could not see beforehand. I think that it was his pragmatism, the very action of painting, that took him there. This also makes me think about this quote in [Carlos] Castaneda’s Teachings of Don Juan, “a man of knowledge lives by acting, not by thinking about acting.”

AWYou mention van Gogh opening a door to somewhere else, somewhere beyond the subject of the painting, which suggests that he saw alternate possibilities to what was immediately before him, both in the landscape, say, and on the canvas. It interests me because, a few days ago, I made a note for the novel I’m working on, in which I say that a finished painting, for all that it might have accomplished, paradoxically contains a meanness of alternate possibilities. This is how the painter knows it’s done, and how a painting gains an air of inevitability. Does finishing a painting feel this way to you—that there’s a closing down of other possibilities—even if it leaves open or suggests a path to another painting?

HAFor me, to finish has everything to do with starting anew. As a matter of fact, I know that a painting is ready when it becomes a promise for another one, when whatever is in the painting, or whatever defines it, starts calling for even more that is not part of it, and that will never be part of it, because it already belongs to the next one—the one that has not yet been painted.

AWThat’s important, what you’re saying. It feels like a metaphor for the ongoingness of life. The way one moment dies into the next. Or, to put it more positively, the way one moment’s end gives birth to a new moment. The idea that whatever is happening now is okay, ultimately, even if it feels negating, because it has a relationship, some direct connection, to what comes next, no matter how different what comes next will be.

HAYes. What makes a work unique can be defined by everything that is the work as much as by everything that is not the work. Everything that is not the work but that could be the work constitutes its transformative potential. This transformative potential works as a promise for another work to come. This idea of a painting becoming a promise for another painting brings me back to what we were talking about earlier: the subject itself, and how it becomes secondary to what it is made of. I think that it is because the subject surrenders to paint that a thing can be painted over and over again without ever being the same thing. It shows us how Cezanne painted Mont Sainte-Victoire over and over again without ever repeating himself. How something as boring and banal as an apple never ceases to amaze us. It explains why every shadow of a plate longs for another shadow of another plate. How every painted cupcake begs for another painted cupcake. How every stroke of color demands another one, consecutively, endlessly, without ever being the same thing.

AWThat thought is happy-making. Your paintings make me joyful. They’re like good memories. Something about the colors and the simplified forms, I don’t know. They make you think, “I have seen these things before. I have been there.” In his book Landscape and Memory, Simon Schama writes something to the effect that landscape is the work of the mind before it can ever be trusted to the senses. That its scenery is built from layers of memory as much as from the strata of rock. Do you employ or think about memory in making these paintings? Is memory important to them?

HAI like this idea of the landscape being made from memories as much as it is made of rocks. In 2014, I took a road trip across the country. I bought a car and drove from east to west, back and forth. The car was a Jeep, so the trunk sat high off the ground. I was painting out of that trunk along the way. I ended up making a lot of paintings—about twenty-seven, I think. I took the trip because I had been living in New York for six or seven years and had never seen the rest of the country. I also read somewhere that one could never be a real American painter without having driven through and seen the country. I think it was Pollock who said that, and I guess I naively followed his advice, or maybe I just needed a good excuse to drive around. I love to drive, and I drove a lot during that journey, sometimes up to thirteen hours a day. I believe you read the small essay I wrote afterward, which I used as an introduction to a book of photographs called driving is awesome. I took the photos through the windshield while driving. I have the book right here. Let me read you just a small portion of the essay: “Around that time, I had already made a few drawings that were drying in the trunk. The car smelled of paint. My friend would ask me to stop here and there, so we could get out of the car and film. While he was filming, I drew. I drew anything. It does not matter. I have so many images in the eyes that I barely have to look around anymore.” As is the case for most of the landscapes I have painted since then, none of these road trip paintings (except for one that is of Spiral Jetty) was of a particular place. These places don’t exist. They were created out of thin air. I think it is because of their archetypal qualities that they induce a feeling of familiarity. Because they were made of piles of memories, of the many nowheres and everywheres that this world has to offer. This perhaps is what makes them relatable.

AWIs painting a kind of sharing for you, then? Maybe a sharing in the delight of being around, of being here—a delight in what’s out there? I’m thinking of something Henry James wrote, and this I have to look up, because it’s impossible to paraphrase him. Here it is: “The very provocation offered to the artist by the universe, the provocation to him to be . . . an artist and thereby supremely serve it; what do I take that for but the intense desire of being to get itself personally shared, to show itself for personally sharable, and thus foster the sublimest faith?” What do you think? Could this be an acceptable form of spirituality for the artist? Is there a place for love in what you do as an artist?

HAI love what I do, although I don’t really see myself as a supreme servant of the universe [laughter]. I am just a humble Belgian painter who happens to live in the here and the now. However, I do like the idea of paintings being portals that open onto a greater beyond. As I said earlier, I suffer from escapism. It doesn’t take much for me to start wandering around. What can I do? I often find myself thinking about paintings as vessels, or as a means of transportation that leads to the many elsewheres that are not the here and the now.

AWSo you are sort of like old Henry!

HAWell, I wish for my paintings to do that for people—to transport them. To take them elsewhere. This is the intimate experience that I hope to share with others. To enter the world of paint: where nothing resists, and everything always remains possible.

Your paintings make me joyful. They’re like good memories. Something about the colors and the simplified forms . . . They make you think, “I have seen these things before. I have been there.”

Andrew Winer

AWAll Things Are Possible—that’s the name of an important book by the existentialist Lev Shestov, who was one of Camus’s heroes and is also one of mine. I guess many of my writer heroes involve themselves in chasing the incalculable, including, as should already be obvious by now, Henry James. James wrote of things intimated by the deep, often hidden processes of living, things that, for this reason, can’t necessarily ever be fully known. Yet if it was seeable, James saw it. He once wrote to a struggling friend that experience, in this case sorrow, comes to us in great waves but is blind, whereas we see. Do you ever feel, when you’re painting, that you’re going after the incalculable or the unseeable, even as you are making something that’s very much meant to be seen?

HAYes.

AW[Laughs] Let me try it this way: If I grant an openness to what’s around me—to that which is—I can sometimes feel that what’s out there possesses so much in excess of what I can perceive or determine. And every once in a while, I get a glimpse of that excess, but, almost immediately, words and names and meaning rush in to claim it. Do you think about this? Do you think painting can sometimes capture that ephemeral in-between moment, just before descriptions and meanings start to attach to what’s being perceived?

HAI am familiar with these moments and with the sense of excess that you describe.

AWPhew!

HAIt’s when a much deeper truth finds itself attached to a rather banal encounter. They often come to me when I am completely detached. When I am not trying to perceive anything. (While peeling a potato, for example.) They come to me as emotions, or as in a dream. But it is almost impossible to hold on to them because these encounters change all the time and never maintain the same form. They are grafted to the perceptual world but escape as we try to seize them or describe them.

AWThey only exist as a flash.

HAYes, and what I feel is that some paintings can revive these moments or feelings in me. They bring me back to a deeper truth when I look at them. Here I am not talking about a deeper meaning, but about an exhilarating moment that is the opposite of meaning. A great sense of silliness or obsolescence that is attached to all things. The reason I think painting or poetry or music can do that is because they are among the very few activities on which meaning loses its grasp. They are in essence very silly and obsolete. They belong to a world upon which rationality does not reign. Very few things can escape the shell of meaning like painting can. And when it does, historians and critics always do their best to bring it back to a rational sphere by describing and naming what should sometimes remain its own language: the unspoken language of paint. When I read about painting, I often feel that this sense of excess is being murdered by a cold and serious analytic language.

AWI pledge not to murder the deeper, silly, unseeable excess of your paintings.

HACan we get that in writing?

AWObsolescence and silliness: you’re reminding me of your countryman Simon Leys’s great collection of essays The Hall of Uselessness, in which he quotes Zhuangzi as having written that everyone knows the usefulness of what is useful, but few know the usefulness of what is useless. At the end of that book’s introduction, Leys writes that the sort of “uselessness” with which he has always concerned himself, as a writer, is the very ground that all the essential values of our common humanity rest on. Is painting “useless” in this way for you?

HASociety mostly recognizes a thing as being useful when it serves a practical function: a coffee machine, a cell phone, an airplane, or a hair dryer. Poetry and painting don’t make coffee, nor do they dry your hair. Therefore, they are considered by most to be trivial and useless. What are these drawings going to do for you? Where is that going to take you, Mister Ancart? These are some things that I used to hear at school when I was caught “wasting” my time making drawings instead of doing whatever task was assigned to me. You are a dreamer, a pariah, a good-for-nothing. You serve no purpose, and you will never be able to find a respectable position within society. For me, making purposeless things like paintings, or writing about nothing, is paramount. I still find hope in these things. They are the opposite of what consumerism demands. Things that exist just for the sake of being, for the love of life, for the spirit. They are essential because they tend to stay away from the tyranny of meaning and the economic way in which the world supposedly turns. Ultimately, these are the things that will elevate us.

Artwork by Harold Ancart © Harold Ancart; photos: JSP Art Photography