Raymond Foye is a contributing editor to the Brooklyn Rail. His most recent publication is Harry Smith: The Naropa Lectures 1989–1991 (2023). Photo: Amy Grantham

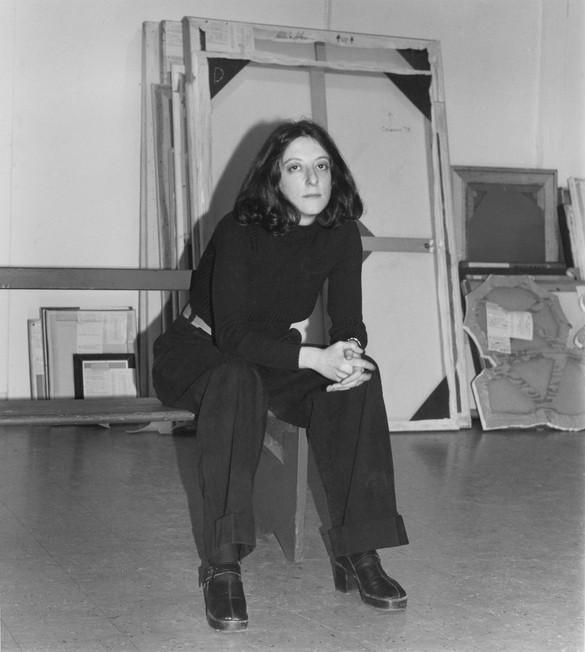

Like a lot of books published in 2019, Out of Bounds: The Collected Writings of Marcia Tucker seems to have been lost in the covid shuffle. It’s been something of a sleeper publication. But this time of dizzying change is an appropriate moment to reflect on the remarkable career of the founder of the New Museum, one of the art world’s greatest mavericks.

A classically trained art historian, Tucker earned her master’s degree at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, where she studied with such formidable figures as Erwin Panofsky and Peter von Blanckenhagen. Tucker referred to von B (as he was affectionally called by his students) as a ribald nineteenth-century aesthete who had stepped out of the pages of Proust. Von Blanckenhagen wedded art history with archaeology, and his painting course began with ancient Egypt—to give a sense of perspective. Panofsky established the field of iconography, an elaborate system of classification of the myriad elements embedded in a work of art: gesture, symbol, myth, botany, astronomy, mathematics, et cetera—essentially the entire panoply of the visual field. An interdisciplinary approach, it was a forerunner of semiotics.

This was an era when art-history books still regularly influenced wider intellectual thought, and Tucker belonged to the last generation of art historians to experience firsthand this rarified lineage of European scholarship. Exacting and exclusive, it was also domineering and chauvinist. Tucker’s graduate advisor was Robert Goldwater, a pioneer in the study of African tribal arts, who assembled the core of the African and Oceanic collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Customs dictated that mostly silent wives accompanied their husbands to faculty lunches, as did Goldwater’s wife, an unknown sculptor and Sorbonne graduate named Louise Bourgeois. Tucker recalled that the standard textbook, H. W. Janson’s History of Art, did not mention a single woman.1

Fortunately this was the 1960s, and Tucker was also hanging out in Greenwich Village folk clubs, riding a BSA motorcycle cross-country, and reading Zap Comix. Her friendly neighbors on 8th Street were the Hawks, later known as the Band. This alternative education would both compete with and complement her academic training, and the tension between the two would play itself out delightfully throughout her career. In 1984, Audre Lorde famously titled a manifesto on institutional power “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House”; Tucker, in her student years two decades earlier, carefully learned the tools, the trade, and how to dwell in this house, then in time tore it down and rebuilt it in her own vision and through her own devices.

Tucker always said that feminist discussion groups and community organizing set the course for her career. In 1969 she began attending the Redstockings, a radical feminist group cofounded by Ellen Willis—a brilliant essayist who wrote as incisively on the Velvet Underground and Janis Joplin as she did on abortion rights, pornography, and Orthodox Judaism. This blend of high and low culture would be a constant in Tucker’s work. Later, Jane Gallop’s Reading Lacan (1985) was an oft-cited book for the way it illuminated the patriarchal biases of Freudian thought—showing how ideas as all-pervading as repression, neurosis, and the subconscious were from the start imbued with sexism. These are things that, once seen, are seen everywhere: “Feminism changed the way I wrote about art and art history and what goes into museums, and offered new ways of thinking about exhibitions. It provided possibilities for different readings of art history and a broad social context for individual interpretations. It encouraged alternatives to the traditional, textual forms of interpretation, such as oral histories, personal narratives, interactive strategies, and fictions.”2

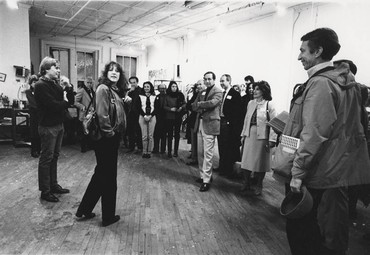

Excluded by the ruling powers, the women who founded their own “laboratory” spaces for art and performance left a remarkable legacy. One hesitates to make a list for fear of leaving people out: in New York City alone one thinks of Alanna Heiss at the Clocktower and P.S.1, Janice Rooney at the Alternative Museum, Martha Wilson at Franklin Furnace, Linda Goode Bryant at Just Above Midtown, Anita Contini at Creative Time, Trudie Grace at Artists Space, Jeanette Ingberman at Exit Art, Philippa de Menil and Helen Winkler at Dia, Dee Dee Halleck at Paper Tiger Television, Corinne Jennings at the African-American alternative art space Kenkeleba House, and Ellen Stewart at La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club. Nurturing and noncorporate, most of these organizations ran on an entirely different set of principles, and an entirely divergent culture was born.

Out of Bounds is structured in three parts. Part one contains seven classic monographic essays, on Bruce Nauman, Pat Steir, Joan Mitchell, Richard Tuttle, Terry Allen, Mary Kelly, and Andres Serrano. Part two includes six catalogue essays from strategic thematic exhibitions: Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials (Whitney Museum of American Art, 1969), which introduced a generation to a new formal and conceptual order through the works of twenty-two artists, including Lynda Benglis, Eva Hesse, Robert Ryman, Richard Serra, Michael Snow, and Keith Sonnier; “Bad” Painting (New Museum, 1978), which challenged notions of “high art” and “good taste,” predicting much of what would take place in the 1980s; The Other Man: Alternative Representations of Masculinity (New Museum, 1987), which examined “how differences of race, gender, class, and sexual preference affect the ways in which we produce, experience, analyze, interpret, and present works of art”; A Labor of Love (New Museum, 1996), which questioned the segregated categories in art, such as craft, folk, and outsider art; and two more. Part three of Out of Bounds, “Institutional Change,” focuses on feminism, race and gender, and the museum as institution, and includes a highly prescient 1994 essay on how the Internet will influence art. These texts are primarily lectures, where fierce critique is tempered by mordant wit.

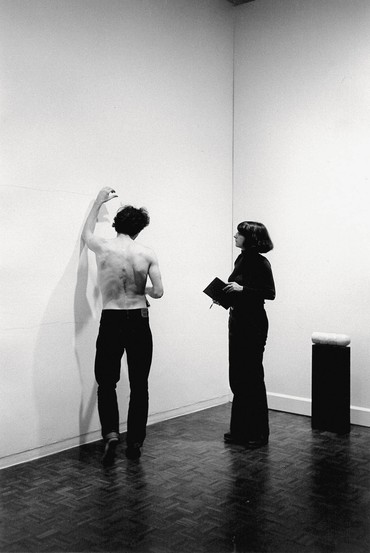

Tucker focused on the trivialization of the art object by consumer culture well before Banksy’s film Exit through the Gift Shop, of 2010. She also understood the limits of formal analysis of works of art. About Tuttle’s 3rd Rope Piece of 1974, she writes, “Some works, like this one, you just can’t explain in formal terms, and you may just have to fess up and admit that it’s just a piece of rope—thereby putting your life in danger.” (Indeed, although showing Tuttle works such as 3rd Rope Piece at the Whitney did not put her life in danger, it did embroil her in controversies that led to her departure from the museum.) Tucker’s language is readable and straightforward, and she never plays the expert, which of course she was. She is intent on maintaining her amateur status, standing on the outside of a work of art, like every other viewer. She includes us in her doubt and bewilderment: “I once told someone that my motto was ‘Act first, think later—that way maybe you’ll have something to think about.’ That could be a recipe for disaster, unless you don’t mind making lots of mistakes. . . . That’s why I’m suspicious of expertise; experts are people who are deeply involved with what they already know, and I don’t want to be one of them.” This humility leads her to always put the artist first, and to eschew the role of artistic power broker.

In gathering different objects to make a show, the curator is not unlike the artist, who is likewise assembling and integrating. The difference is that one is organizing and the other is actually creating. Tucker understood this difference and never took the next step of curator-as-artist arrogance. Her essays propose questions, not answers. When she left the New Museum, passing on the leadership to Lisa Phillips, she took to the lecture circuit. A natural entertainer, she enjoyed sharing her love of art with audiences of all sorts.

In her last decade before she died, she was raising a child, working as a freelancer, and struggling with the cancer that took her life. She wrote a play about the art world, started a musical group, and did stand-up comedy. She was also studying Tibetan Buddhism and Zen with the same humility and insight that she had brought to her career as a writer and curator. In her last essay—“No Title: Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art,” published in 2004 (two years before her death)—she explores the themes that had drawn her to the works of Nauman, Mitchell, and Tuttle three decades earlier: emptiness, awareness, ephemerality, and presence. In this, her final meditation on art, she reveals the secret behind all her insights: compassion.

Tucker’s career was a critique of the power structure that surrounds and simultaneously degrades art. She was among the first to explicitly understand that museums were as much about wealth and power as about art. In enumerating the many social injustices on which these institutions were based, she predicted the coming storm that would engulf the museums of today, to an extent that might have surprised even her. A full twenty-five years ago she wrote in the New York Times, “When I was a child in the 1940s, the idea that an art museum could be the target of controversy was like imagining a three-hundred-pound ballerina as the lead in Swan Lake. Yet today, just fifty years later, contemporary art museums have become nearly synonymous with pitched battles over the nature, value, and financing of art.” Ultimately her message is one of hopefulness. When she writes that “every act of making displaces an act of unmaking,” Tucker understands that art is one of the few viable forms of optimism left to us. No one who cares about art can afford to be ignorant of what she accomplished.

An Interview with Lisa Phillips

RFShe is so prescient about, well, practically everything.

LPEverything. I have kept trying to channel her over the last few years. What would Marcia do? What would Marcia say?

RFI wanted to ask, Do you do that?

LPI do. Especially now, when there’s so much change going on in the world. When I started at the New Museum, she had just retired, and we got quite close. She was a wonderful mentor and spent time with me; we had regular meetings. She gave me lots of advice.

RFSuch as?

LP“Don’t let this job kill you!”

RFWas she intimidating? You were very young when you started out working with her at the Whitney.

LPI didn’t know her very well at the Whitney, I just admired her from afar, and I certainly found her intimidating then, but she really wasn’t. She was just intense. And accomplished. And young. She was still in her early thirties and doing amazing work at the Whitney, and I was in my early twenties.

RFDid she focus on you at all?

LPNo, not really. But I did work in the Richard Tuttle show—I was stationed in the galleries to answer the questions of perplexed and often angry viewers, who demanded to know “Where is the ART?!” The walls looked bare at first, but then his subtle interventions became apparent. At that point I was still figuring everything out, and I thought, Oh, she’s doing something courageous here and making a difference. I understood that women could do something important in museums that was worth aspiring to. She was definitely a role model, but we weren’t close then. I knew her and I observed her in action. Then when I came to the New Museum she couldn’t have been more generous with her time and her experience. Really funny, open, not at all intimidating.

RFShe’s extremely funny—that comes through in the book, especially in the lectures section, which balances the book in a different way from the writings. Is it true she did stand-up comedy?

LP Yes, she did. The lectures that she staged for donors at the museum were really performances, and they were just hilarious. She brought that humor and performance to everything she did. I can’t think of another person in the museum field who behaved like that, always bringing humor and the unexpected and the performative to everything she did. Gallery talks, board meetings, whatever it was, it was just so refreshing and great. She always pushed herself to do things out of her comfort zone. She loved music, loved to listen to it and wanted to sing, but she had a terrible voice. So she joined an a cappella group and got so much pleasure out of that. In taking on these challenges she also questioned what’s terrible and what’s beautiful. She was constantly inverting our expectations about values: embracing bad painting, bad girls, et cetera, as positives.

RFI think people sometimes forget that there’s a certain amount of showmanship in organizing an exhibition, be it at a gallery or a museum. People who understand that just seem to do a better job.

LPShe really made a virtue out of the questions “What am I doing here? How did I get here?,” and turned those expectations upside down through humor. I think that was part of her brilliance.

RFI imagine she had to fight for space at the Whitney, like every curator?

LPYes, but she was very good at claiming these interstitial spaces, like in the basement between the café and the restrooms, where she mounted a show about tattoo artists and another about body builders. Those are good examples of how a lot of Marcia’s interests that seemed very “out of bounds” at the time became mainstream. She was always paying attention to artists and art forms that were disparaged or overlooked.

RFWere there frustrations you had working with her later on at the New Museum?

LPNo, and I never really worked closely with her. She’d already left before I arrived. She had one last show at the New Museum that opened while I was there, The Time of Our Lives, which was about aging, and she was very graceful in how she exited. She had moved everything out of the office and then just came by and said, I’m available to provide whatever support or resource you might want or need, I don’t want to impose myself. She was very happy to see that the New Museum was going to continue on, she was very proud of that, and she was ready to let go. She had been fighting a serious illness for several years and wanted to spend her energy differently. It was a natural transition for her. She was just so gracious and kind to me, and gave me a lot of sage advice—she was definitely like a mentor and a big sister. At that point I was already in my forties and I’d had quite a bit of experience myself, but she knew the New Museum better than anyone.

RFDid she have a difficult time with patrons or with her board?

LPI don’t know, because I wasn’t there. I think they really loved her—she was a pied piper, she always had a strong following. But I’m sure it wasn’t always easy.

RFAfter the Tuttle show at the Whitney and her departure, did you ever have any doubt that she could pull off the New Museum?

LPWell, it was such a tiny place when it started out, it was one room. The first location, in 1977, was at 105 Hudson Street, where Artists Space was. She opened it within about a week of leaving the Whitney, with about $15,000 and three part-time volunteers, and she was unpaid. Of course we all went there. I knew people who worked for her, like Allan Schwartzman, who had also been an intern at the Whitney—he went along with her, he was about nineteen years old. In 1977, Vera List provided room at the New School for Social Research for the New Museum, and in 1984 the museum moved to Broadway near Houston, to a building that had no roof, so obviously the ceiling leaked. It was a time when people were starting their own organizations left and right, so the New Museum didn’t seem out of the ordinary or strange because it was an alternative space, it wasn’t a big institution. Yes, it had a big ambition, being called a museum, but it was a very small space. At the time that didn’t seem odd at all.

RFThe decision not to have a collection—was that just practical and financial, or was there a political dimension to it?

LPThat’s an interesting question. The New Museum did have a “semipermanent collection.” Her idea was, How can we collect and do it in an unconventional way and in a way that keeps it contemporary? So she said, Let’s collect and then sell the work after ten years and buy new work. That didn’t work out particularly well, because artists don’t like their work to be sold, number one. What happens if the market for an artist’s work is weak and it doesn’t sell? Collectors didn’t love the idea either. It was an interesting concept but hard to put into practice. I think Marcia felt that not having a collection was probably the way to go, to stay more rooted in the present moment.

RFIn the Collected Writings one gets the sense that she was thinking on her feet all the time and adapting to new situations as they arose.

LPExactly. But always bringing to bear the seriousness of museum practice and of scholarship.

RFShe strikes a great balance in her writing, because she does believe that art is for everyone, but she’s never dumbing it down.

LPOne thing about Marcia is she spoke about art in very plain language, and that comes through in the book. There’s no academic jargon or artspeak, it’s very direct and readable. That’s something we should all strive for.

RFShe’s also somebody who can really call out bullshit when she sees it, and there’s nothing like that.

LPI know, and that’s when I really want to hear her voice these days. What would she say to some of the things that we’re experiencing right now? How would she respond? She was very outspoken and direct, as you know.

RFAs radical as her approach was, she also seemed to believe in working within the system, to create institutional change from within, and I think she was criticized for not being radical enough, right?

LPThat’s right. It’s important to remember she had her own struggles, too. She wasn’t always in a position of power. We’re operating inside a culture that has certain values and structures, so what are you going to do? Either you choose to blow it all up or you’ve got to work within it somehow. Marcia often said, “The only way I could be a museum director was by starting my own museum.” Women simply were not hired for the top positions in those days. Also, she was increasingly troubled by the corporate direction she saw museums taking. But in time what she created became an institution and the market also caught up to it—an irony that was not lost on her.

RFReading this book, you realize that if you can’t write, you really are at a big disadvantage as a curator. Think of all the great curators we’ve known, and how many of them didn’t write. That’s what’s great about this book: it memorializes Marcia Tucker not just as a writer but as a curator and thinker. So many museum curators aren’t remembered for just how interesting they were.

LPIncreasingly that’s a challenge many young people face. The Internet and social media don’t really encourage good long-form writing.

RFI think we’re all a bit amazed at the transition we’ve seen the Whitney go through in our lifetime. And if you look back at exhibitions like Anti-Illusion, Marcia had as much to do with this change as anyone.

LPAbsolutely. Her radical vision changed the Whitney permanently. I started working there in 1975, so Marcia and I overlapped by several years. Back then, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s daughter Flora Miller and granddaughter Flora Biddle were in the museum daily. It was still a family operation in many ways.

Just to set the record straight, Marcia was not fired from the Whitney because of the Richard Tuttle show. The implication that the work was too radical for the museum was definitely not the case. She just had a really fundamental clash of style—and perhaps values—with the then new director, Tom Armstrong, and things became untenable. It was disappointing to some that the catalogue didn’t come out until after the show. Marcia wanted a publication that would include installation views and all of the critical reaction to the exhibition as part of the catalogue, but that meant there was not much for the public to read to learn about this quite mysterious figure who was making extremely minimal work.

RFIt’s an interesting concept, that the catalogue needed to contain the responses of viewers and critics, as if that completes the artwork in some way.

LPResponses to art are shaped by social considerations and cultural conditions and those things were very important to her. Her ideas were courageous and unconventional, and maybe they didn’t always work out in every situation, but she always said you had to be prepared to fail. Clearly she was moving beyond a traditional institution and felt increasingly stifled there. Her feminist consciousness and commitment made it hard for her—it was a tough time for women in any institution at that point. So I take very seriously what she said about needing to start her own place in order to have a position of power. Most of the alternative spaces that were started around that time were founded by women, and that’s not lost on me either—that generation of women who started their own institutions paved the way for my generation to have other options. Many options.

RFWhat was the evolution of the book from the editorial side?

LPAfter Marcia’s death, in 2006, her husband, Dean McNeil, handed me a folder and said, “This was a project Marcia was working on. Would you see it through to completion?” Johanna Burton and I read through all the materials and all of Marcia’s notes. Alicia Ritson did a lot of the subsequent research with Kate Wiener. They both spent a lot of time at the Getty Research Institute, where her papers are. The book had a long evolution and we tried to be respectful of how Marcia thought it should be structured. Johanna and I worked closely together, reading through everything. We made several trips out to the Getty and then eventually edited the selections down to what we thought would make a strong presentation of the different themes that Marcia had laid out.

RFThe last essay in the book, “No Title: Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art,” is a beautiful summation of so many important themes in her work: attentiveness, demateriality, and the value of experience over information.

LPI think her interest in Buddhism started before her illness, but then she took it to a whole other level. That was probably during the last decade or so of her life. I remember hearing about these retreats that she would go on that sounded great. I think she had a fair amount of tension in her life that she had to contend with, whether it was financial pressures, her illness, or family situations—things we all contend with. And you think, Yeah, this woman can handle anything—she’s a powerhouse and a force of nature, she can handle it all. But she struggled like everyone else does and found solace and a path through Buddhism.

Marcia and I are very different people. We never really worked closely together but we became closer in those last ten years of her life. We both had our children at the same age, and there was a lot that we shared and struggled with as professional women and working mothers. I love reading her writing and I feel very grateful that I had the opportunity to bring this book to fruition, and I hope people will read it and it will inspire future generations of women. And other people, not just women.

1Marcia Tucker, Preface, in Art Talk, ed. Cindy Nemser (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1975), quoted here from Andrew Perchuk, Foreword, in Tucker, Out of Bounds: The Collected Writings of Marcia Tucker, ed. Lisa Phillips, Johanna Burton, and Alicia Ritson, with Kate Wiener (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute; New York: New Museum, 2019), p. viii.

2Marcia Tucker, A Short Life of Trouble: Forty Years in the New York Art World (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2008), p. 88.