Jewels Dodson is an arts and culture writer and producer. She started her career writing and editing for street-culture magazines throughout New York City. Her work can be found in Juxtapoz, Artnews, Artsy, The Cut, and the New York Times. Most recently she launched The Shortest of My Tall Thoughts, a micropod in which she examines cultural theories and trends.

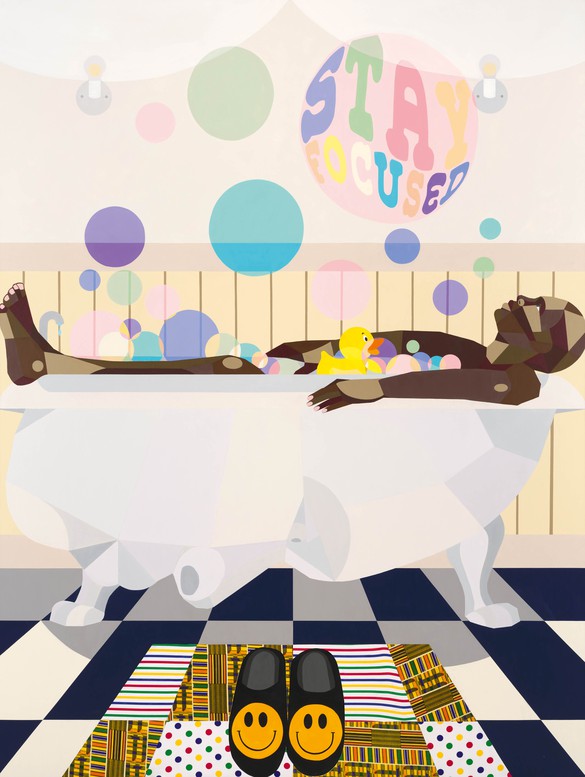

A young Black man lies in a white porcelain claw-foot tub, enveloped in colorful soapsuds. His languid leg hangs over the tub’s curled edge and his head hangs heavy as he soaks away the day’s stress. He is in a state in which we rarely get to see Black men, unsheathed and vulnerable. Though all the current talk of “soft life” is directed at women, softness looks good on this guy. A pastel thought bubble floats above his head: “Stay focused,” not only a reminder but perhaps a prayer to hold steadfast to his dreams—ambitions that could easily be decimated in the minefield that is Black manhood in America. Deep in the sanctity of his solitude, his humanity permeates.

Happy Place (2023) is a work in Derrick Adams’s new exhibition Come As You Are, on view at Gagosian, Beverly Hills, from September 14 to October 28, 2023. The show contains new works of substantial scale, each embedded with Adams’s codified themes of joy, inclusion, and quiet rebellion. The title Come As You Are derives from an adage in the Black church, which appears to be accepting of those on the margins but is laden with exclusionary fine print. “When I hear that phrase I always think ‘inclusivity’ and very particular personas being welcomed. People with unique personas and characters. Like when people are extra, I think about those people coming. These paintings are really about those kinds of characters,” Adams explains.

In Put Your Foot In It (2023) a crème brûlée–complected woman, her scantily clad upper body covered by a collard-green leaf, the rest of her body replaced with a chicken thigh, lies on a platter. The platter is held up by another female subject, whose black jacket and white cuff allude to being waitstaff. “Yes, she’s serving,” Adams says with a childlike chuckle. “Black people will see this and know this a conversation for them.” In this series, Adams doubles down on humor. “It’s like Black people making fun of themselves in an empowering manner,” he continues, “It’s not self-deprecating, it’s really more about being able to understand yourself in a multidimensional way. Do Black people get to enjoy that without feeling like the butt of the joke?” Adams ponders aloud. His imagination is in full throttle; the imagery is wonderfully whimsical. “This is more about my ability to look at myself in Black culture in a way that could be humorous,” he expounds.

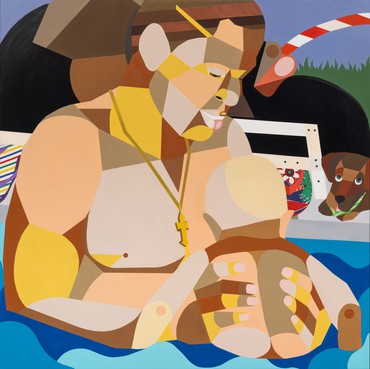

Come As You Are takes us structurally and psychologically higher into the Adamsphere. He establishes more layers in the work, growing more complex in space, compositional structure, and color use, including his creation of melanated skin tones—his take on Black skin is as dynamic as the fraught history that created it.

Psychologically the entire series is laden with masterful use of cultural iconography, pop-culture colloquialisms, and clever double entendres. In Be the Table (2023), two fierce female figures face each other wearing winged masquerade masks—one sports a bird, the other a butterfly. Centered between the two subjects is another female figure who appears as a floating head on a table, the rest of her body being out of view. “For our yearly family costume parties everyone would dress up, and one year my aunt came as a table. I decided to paint her for the show,” Adams says. It’s a cunning and campy play on the notion of having a seat at the table: “Be the table and you won’t need a seat,” he says. We both cackle at the witticism. In the Adamsphere, inclusion is a verb, and he makes space for everything Black people are and everything they can be.

Adams has long been making space for folks in the margins. While this Baltimore native pursued a BFA at New York’s Pratt Institute in the early ’90s, he also began working at the clothing label Phat Farm, where he got an intimate look at urban style and consumer culture. Both are still embedded in his lexicon. Later, under his stewardship, the Chelsea gallery Rush Philanthropic Arts Foundation became a hub for New York’s Black art community. At the time, Rush was one of the rare spaces in New York to see Black art. Early exhibitions included Simone Leigh, Lyle Ashton Harris, and Xenobia Bailey. Within the art world, Adams is known to be a champion of emerging artists. Wangechi Mutu, Nathaniel Mary Quinn, and Deana Lawson all caught his attention and won his support early in their careers.

A core tenet of Adams’s painting is centering the Black figure, which he does more intently than ever in his latest body of work. He eliminates the white gaze with Morrisonian fervor, putting Black subjects at the forefront and building a world around them—a steep contrast to most Black people’s reality, which often requires contouring themselves to fit into a white space. Adams centers Black figures in order to empower them enough to explore new mental, emotional, and spiritual frontiers.

In creating these scenes, he gives onlookers license to break from the small spaces they’ve been assigned to, to be who they’ve always wanted to be, to be who they really are.

In extricating Black subjects from the white gaze, Adams releases them from expectations of being politically representative, allowing them to exist instead in a fantastical utopian universe of his design. “Knowing that the content is already embedded in the subject is liberating me to really have fun painting the figure and painting the world around the figure,” he says. “Now that they’re centered, the possibilities are endless.” In creating these scenes, he gives onlookers license to break from the small spaces they’ve been assigned to, to be who they’ve always wanted to be, to be who they really are.

Adams challenges the larger narratives imposed on Black figures, and inevitably on Black artists, while still working with figuration. When Black artists such as Ed Clark, Norman Lewis, and Howardena Pindell made abstract work, brilliant but seemingly apolitical amid racial turmoil, they didn’t align with the Black culture of the time, and came under fire. Making work through an apparently raceless, genderless lens was deemed frivolous and flippant. To make work freely without a descriptor is a privilege afforded mostly to white male artists. Over time it became defiant to not “represent,” but instead to direct attention to more poignant ideas and issues addressed. Adams, like his predecessors, isn’t perpetuating the stories commonly attached to Black figures. What stance is more powerful than making work rooted in humanity about and for people who were once considered property?

While taking the MFA program at Columbia University, Adams became interested in the multiplicity of Blackness. He didn’t feel bound to a particular narrative; inspired by senior artists including Clark and David Hammons, Adams’s view of Blackness expanded. “I thought it was open. I thought you could make whatever you want,“ he continues, “They created that space of Black artists working in this centered way. People were just not ready for it. It took a while for people to understand the freedom of Black artists understanding themselves as being centered.” His style was challenged by his professors: “You’re not pushing against anything, there’s no tension,” was the feedback he received from two art-world juggernauts, whose work is often characterized as provocative. “I remember one instructor telling me I was suffering from Black middle-class denial,” Adams recalls.

“Because they were radicals, responding to my work so negatively, I thought it was radical. If it wasn’t so radical, [they] wouldn’t be making this big a deal. It was triggering, it was doing something,” Adams concluded. He decided to forge ahead presenting vast versions of Blackness, versions including lace-front wigs, leisurely summer days, family gatherings, joy, and vulnerability. In his discovery of the nuances of Blackness, Adams puts value and worth on all types of Black experiences. He creates truly inclusive worlds where the table is grand and there are seats for an abundance of perspectives, experiences, and identities. Adams doesn’t fall prey to the respectability politics that so often come with the validation of Blackness; for him, fitting into a white scheme is not a prerequisite to being valued. In the Adamsphere the distinctive elements of Blackness are beloved.

Derrick Adams: Come as You Are, Gagosian, Beverly Hills, September 14–October 28, 2023

Artwork © Derrick Adams Studio; photos: New Document