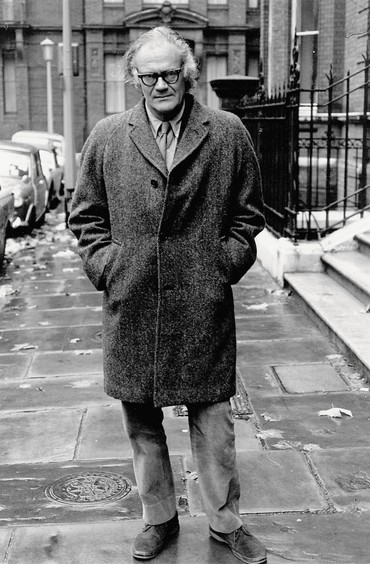

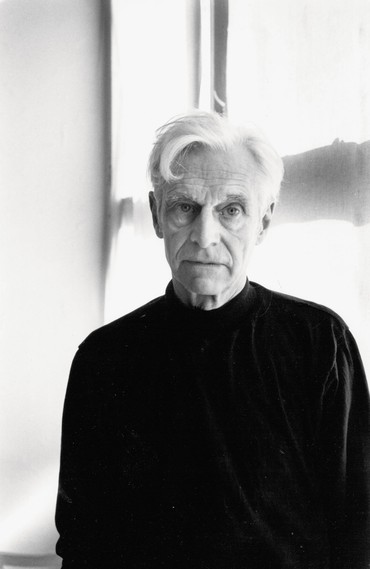

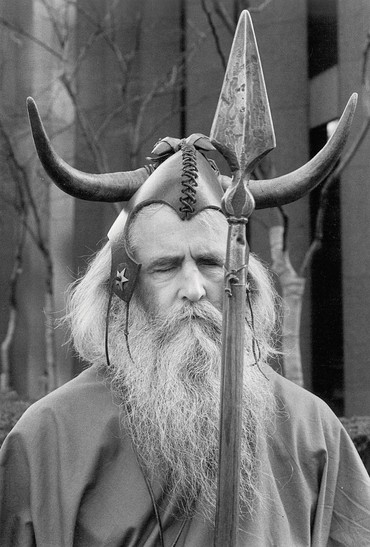

Raymond Foye is a contributing editor to the Brooklyn Rail. His most recent publication is Harry Smith: The Naropa Lectures 1989–1991 (2023). Photo: Amy Grantham

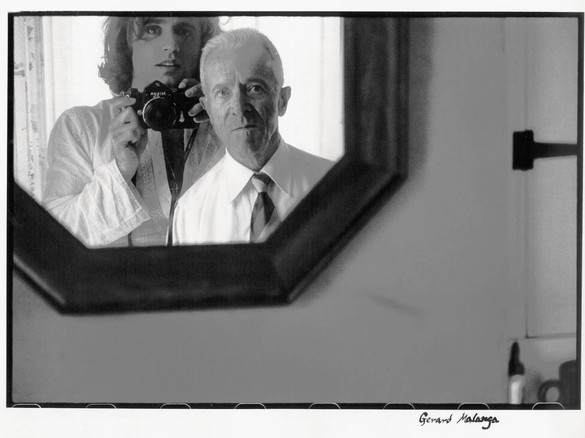

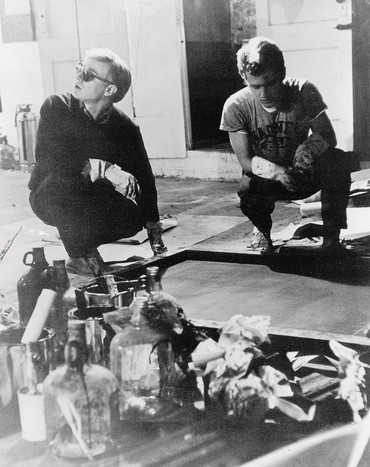

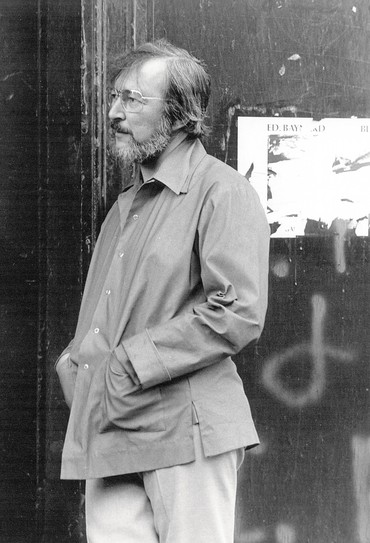

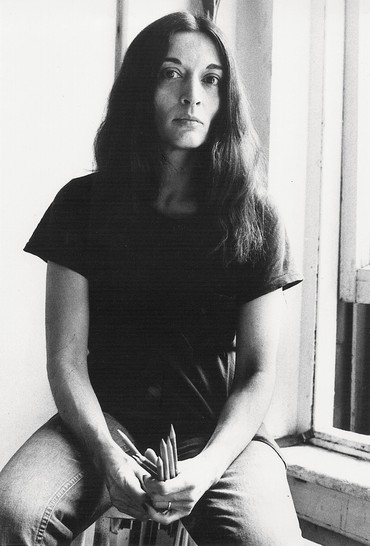

Gerard Malanga is the author of fourteen books of poetry, including his most recent, The New Mélancholia & Other Poems. A selection of writings on his movies, Gerard Malanga’s Secret Cinema, is forthcoming from The Waverly Press. He is currently compiling a monograph of his photographs, Moments in Time. He lives in the shadow of the Catskills with his cat, Odie. Photo: William Wood

Gerard MalangaIf I had to pinpoint where my artistic life began, it was a photo book called Metropolis: An American City in Photographs, by Agnes Rogers and Frederick Lewis Allen, published in 1934 by Harper & Brothers. When I look back at this book I realize that in my adolescence, technically I was training my eye for the future, although I didn’t know it at the time. I realize now that I was involved with photography before I ever thought of picking up a camera. I grew up in the Bronx and my parents wanted to keep me off the streets after school let out at 3 o’clock, so they enrolled me in an art class at the local YWCA. In the art room was a bookcase with this book. Every time I went to class, I took the book off the shelf and went into a corner to look at it. Basically, at the end of the school year I charmed the teacher into giving me the book.

Raymond FoyeThe book is thematically organized around how a city functions during a twenty-four-hour cycle.

GMYeah, so that was interesting. Tugboats, clipper ships, beggars, children’s games, subway shots, tenement life. The photographs, by Edward M. Weyer, are in beautiful black and white.

RFIn what ways was the Bronx different from Manhattan?

GMWell, physically it was different because it’s the only one of the five boroughs that’s part of the mainland. The Bronx was farmland and woodland in a lot of places when I was growing up. It was also the last borough to be settled, so it was a very young borough in that sense. Our house was two blocks from Edgar Allan Poe’s cottage. My primary school was PS 46 Edgar Allan Poe. As a kid, I had a choice of six movie theaters in my neighborhood and I would go twice a week. It was a great diversion. My favorite theater, the Valentine, showed re-releases or else foreign films with subtitles, a real educational experience.

RFWhat was high school like for you?

GMI went to the School of Industrial Art, today the High School of Art and Design. When it started, back in the 1930s, it was a WPA school, a vocational school. I majored in advertising and graphic design. My classmates were Calvin Klein, Antonio Lopez, and the Kuchar brothers, who were studying film. We were all in the same class. It was a terrific school. Calvin Klein was doing costume design, Antonio was doing fashion illustration—a field he would revolutionize. When Antonio showed me his portfolio, my jaw dropped. I thought, Wow, you’re going places! He was quite amazing. I was always clothes conscious, even before high school. When I was young, my mother always used to dress me up with a tie and a clean shirt. We were all Bronx guys, we all lived within about two miles of each other in the north Bronx, two subway stops from the end of the line.

Antonio Lopez had a great collection of 45 rpms that he would bring to school, and we used to dance to them in the cafeteria during lunchtime. We would have a ball. Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, that sort of thing. Antonio also had mambos and cha-chas, which he taught me how to do. And in connection with that, one day I ran into an old girlfriend on the street, Judy Klein. She was on her way to the TV studio where they were shooting Alan Freed’s show. She said, You like to dance, come on with me. I knew about Alan Freed—more than anyone, he was responsible for introducing rock ’n’ roll to America—but I didn’t know he had a TV show. Judy brought me to the DuMont TV studio on East 68th Street and I became a regular on the show until the very end. We were dancing to records but we did have live rock ’n’ roll visitors like Tina Turner, Chubby Checker, Bobby Freeman—he was a favorite of mine. These acts lip-synced to the records. There’s a picture of me in the December 7, 1959, issue of Life. They covered the last day of Freed’s show—he was put off the air because of a payola scandal. I have a crew flattop and I’m talking to my date. We wore our own clothes to the show because we were always picking up the latest styles on the street. We shopped for shoes at McCreedy & Schreiber, and in midtown Manhattan there were some really nice clothing shops for young people.

RFWas there a point when you had to decide what you wanted to be? A writer, an artist, a designer?

GMBy the end of my last year of high school, I had already decided that I was going to be a poet. That was because of the poet Daisy Aldan, my English teacher. She was remarkable—we were reading incredible stuff in class, material that probably wasn’t being taught in any other high school English class in New York, or even in the university system. I was reading Wallace Fowlie’s books on Surrealism. She brought poets to class to read their work, like Jack Hirschman, who was a Bronx guy, and Kenward Elmslie, Ruth Landshoff-Yorck. Daisy even brought Anaïs Nin to class to read her work, she was a close friend. That never happened in any other high school in the city, I’m sure. During the last year of high school, I started going to poetry readings, just to hear how poetry is read. I thought it was very glamorous, taking the subway into Manhattan to hear somebody read poetry.

RFWhat was her magazine called?

GMFolder. She published three or four issues. It was a portfolio of separate sheets of poetry and art. And then when I was a senior in high school she brought out an anthology, A New Folder, that collected all of the earlier material.

RFWho were your favorite poets back then? Who were you modeling your work on?

GMThere were two models. The first was Frank O’Hara, whose work seemed very new and very accessible. Then John Ashbery, a little bit later, when The Tennis Court Oath [1962] came out. That was my bible. I used to carry that book with me, it was incredible. It was very romantic in a way, also very dreamlike because of all the disconnects between words and images. It just seemed mesmerizing. Kenward Elmslie also made a big impression on me when he came to class as a guest of Daisy Aldan’s. I decided to interview him for the school newspaper, naively thinking he was a Beat poet, so he must have gotten a big laugh out of the questions I was sending him. He invited me to a party he was giving at his house. This was April 30, 1960. It was called the Big Loyalty Day party and his house was decorated with red-white-and-blue Uncle Sam dolls, all kinds of Americana. It was like going to a Hollywood party: everybody was there, the painters, the poets. It was an unbelievable experience. That’s where I first met both Willard Maas and Frank O’Hara, who walked in with Bill Berkson. Bill was the only person I really knew at the party, so I went up to say hello and introduce myself and he snubbed me. Later we became friends, but it was awful.

RFHe snubbed you because you were a nobody at the party?

GMOh, absolutely. We were the two youngest people at the party so maybe he didn’t want to acknowledge me for that reason, I don’t know. Then Daisy walked in and said, What are you doing here?! I mean, I’m her student, I’m going to see her in class the next day, you know?

RFSo this was 1960. I’m curious, at what point did you get a sense that the ’50s were over and the ’60s had begun? When did you feel the decade shift? Because these things don’t always change exactly on the year.

GMI think it had to do with the music. It had something to do with when the Beatles and the Rolling Stones arrived. The feeling of the music, it just kind of liberated you. There was a certain excitement, a certain wildness, a certain rebellion that came with rock ’n’ roll. It was a new kind of music that you couldn’t put your finger on. You just went along with the rhythm.

RFMiriam Sanders once told me that she and Ed were at home in their apartment on Saint Mark’s Place and Allen Ginsberg rang the doorbell and came rushing upstairs very excited. He had a copy of TV Guide and on the cover was a picture of the Beatles. This was in February 1964. And he said, “Look, this is the new thing. The beatniks are out, it’s rock ’n’ roll now. This is what we have to follow.”

GMWell, Allen was certainly on the beat. I went with Andy [Warhol] and Isabel Eberstadt to the first New York performance of the Rolling Stones, October 24, 1964. They were performing at a huge movie palace called the Academy of Music, which was on 14th Street. We were in a limousine slowly pulling up to the venue and we began to get completely mobbed, because I had longish hair and was wearing a pinstripe suit. One of Andy’s collectors at the time had given me three of his old suits that didn’t fit him anymore. These kids were knocking on the window of the car, and I said, “Isabel, what’s going on here?” I didn’t catch on to the situation, but Isabel said, “Oh, they’re trying to get your attention. They think you’re one of the Rolling Stones.”

RFYou were in a limousine because of Andy?

GMNo, Isabel. She was writing a story on Andy but it never got published. We finally got into the auditorium and the Stones came out. They were dressed like they had just fallen out of bed. They were spitting on the stage with such attitude, and the fans were racing to the front of the stage and getting thrown back into the crowd by the guards. It was just an amazing, phenomenal experience. Sheer pandemonium. Incredible.

RFAnd what was Andy’s reaction to it all?

GMHe was being very quiet about the whole thing. A month later Andy and I went to the Brooklyn Fox Theatre for Murray the K’s holiday show to see Dionne Warwick. We went backstage to meet her.

RFWhat did you do after graduating high school?

GMIn the summer of 1960 I got a job with a very successful fabric designer named Leon Hecht. Leon had been in the 1953 graduating class of the School of Industrial Art and then went to Black Mountain College. He was a former student of Daisy Aldan’s and she put us in touch because she knew I needed a summer job. I learned to silk-screen from Leon’s textile chemist, Charles Singer. We used to silk-screen thirty yards of prestretched fabric that was then cut up to make neckties for a company called Rooster. The workshop was on the top floor of a tall building on Broadway and East 3rd Street. That skill came in handy later on. In the fall I went to the University of Cincinnati for a year and flunked out.

RFYou didn’t take to university life?

GMI was pretty much a bohemian at Cincinnati, which was a very conservative university, so I was isolated. One good thing was that I made friends with Richard Eberhart, who was the visiting poet in the spring semester. It was a wonderful experience. And Daisy wrote to Eberhart to say, Look out for Gerard because we want to keep him, we don’t want him to get in any trouble.

RFWas he a good poet, Eberhart?

GMYes, he was a good poet. His poem “The Groundhog” [1934] was highly anthologized at that time; it was a very, very popular poem. I kept the friendship going after I came back to New York, and I photographed him on the rooftop of the Chelsea Hotel when he was staying there in 1975. By then he was teaching at Dartmouth.

RFThen you went to Wagner College?

GMWhen I came back to New York in 1961, Willard Maas arranged for me to go to Wagner College, a small college on Staten Island where he taught English. Willard’s wife was the filmmaker Marie Menken. I’d gotten to know them both by that time. They were famous for their battles and drunken parties. Edward Albee taught at Wagner College in those days, and it was pretty clear that he based the lead characters in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? [1962] on Marie and Willard.

RFSo you transferred in?

GMWell, because I’d flunked all my freshman courses, I would have had to take them all over again. A deal was worked out where I got what was called “an anonymous fellowship to advance my creative abilities.” Years later I found out, or I kind of guessed, who the anonymous donor was: Kenward Elmslie. So in the summer of 1962 I enrolled in Robert Lowell’s class in the writer’s conference at Wagner. Lowell was a big deal, and a remarkable teacher. He’d already been awarded the Pulitzer Prize. I was actually given the first Gotham Book Mart poetry prize, which was awarded to me by Robert Lowell, based on that summer workshop.

RFWere you living at home again?

GMYeah, I was living in the Bronx, so I was commuting to Wagner three days a week to get to a 9 o’clock class. I’d have to catch the D train at 6:30 in the morning, change trains downtown to get to South Ferry, take the ferry to Staten Island, and then two bus rides to get to Grymes Hill. That was easily two hours. Then back home at night.

RFHow long did that last?

GMNot long. I dropped out in my sophomore year. I couldn’t keep up the schedule, and besides, I’d already met Andy. Three days a week I would go from school to the Factory, where I worked five days a week. I just could not keep that schedule going, it was one or the other: Am I going to go to school or am I going to work for Andy? I decided on working with Andy and I dropped out of college. Willard was very upset about this.

RFHow did you meet Andy?

GMThrough Charles Henri Ford, who knew that Andy was looking for a silk-screen assistant.

RFHenry Geldzahler once told me that Andy asked him to bring him to Rauschenberg’s studio, so he could see how Bob used silk screen.

GMYes, but to wind the clock back even further, there was a guy named Richard Miller, who was Daisy Aldan’s ex-husband. He and his boyfriend had a greeting card company called the Tiber Press, and Andy was actually in dialogue with both those guys about silk-screening because they were silk-screening certain sheets for Daisy’s Folder.

RFDid you have to go for an interview with Andy?

GMNo, I was available and that was it.

RFWhat was your impression of Andy that first day?

GMAndy looked like somebody from planet Mars. He was a guy with sunglasses and silver hair. Strange looking. He asked me to come to work the next day. I said, I have to clean out my desk at school, I’ll come the following day. The first thing we did was a silver Liz painting. Andy showed me how he liked to have certain things done with the printing. This was well before the Factory, it was an old firehouse Andy rented from the city for $100 a month.

RFWere you keeping a diary at this point?

GMBack then I only kept a diary off and on for about a year and a half. I couldn’t live my life and keep a diary at the same time. I just didn’t take to it in the end. It’s hard to keep one going; you have to be religious about it.

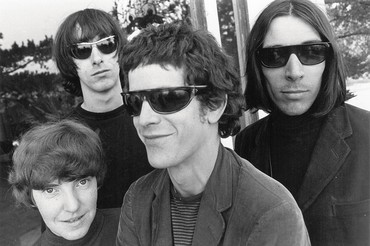

RFThere’s so much to discuss about this period, but there are two things I specifically wanted to ask you about. One is how the Velvet Underground got involved at the Factory, and the other is, Where you were when Andy was shot?

GMWell, I was introduced to the Velvet Underground by the filmmaker Barbara Rubin, who took me to see them at the Cafe Bizarre in Greenwich Village. It was a small club, no stage, everything on one level. There were a lot of teenagers there. The Velvets started to play and Barbara urged me to get up and dance because everyone was sitting there not moving. By chance I happened to have that leather whip with me, which I’d bought at a store called Sammy’s Whips and Umbrellas on the Upper West Side. They sold umbrellas and whips, a strange combination. I didn’t buy it to whip anyone with, I just bought it as a fashion accessory. Anyway, I got up to dance, and eventually I was using the whip, and suddenly all the other teenagers in the audience got up and started to dance, which the band was very happy about. We thought the Velvets were great, and a few days later we came back with Andy to see them again. Andy loved them and he offered them the use of the Factory to rehearse, which was a wonderful thing to do.

RFWhat do you remember about the shooting?

GMI wasn’t still working for Andy at that point, 1968, but I happened to be going to the Factory that day because Andy was giving me a check for $50 to have a flyer made up for my first movie program at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque, when it was down on Wooster Street. I could have run into Valerie [Solanas] in the elevator because I arrived just after he was shot. He was still on the floor and Billy [Name] had Andy’s head in his lap. I think he was half conscious; he was in a lot of pain.

RFThat must have been horrifying.

GMIt was pandemonium. People were running back and forth. I saw Paul Morrissey and the first thing I said was, I’m going to go get Andy’s mother, where’s the hospital? He said, Take a taxi, and gave me some money. I didn’t take a taxi because it would have taken too long to get up to Andy’s house. I took the subway to 86th Street. Julia [Warhola] had a curtain on the front-door window so she could see who was outside. She recognized me and opened the door. At just that moment the phone rang. I said, Let me get that. I ran up the stairs and it was a friend of Julia’s from Brooklyn who’d already heard on the radio that Andy had been shot. I said to the woman, I’m here to take Julia to the hospital, everything’s OK, thank you for calling, goodbye. It took Julia about fifteen minutes to get ready—she was dressing for winter when it was summer outside. We took a taxi downtown and I told her that Andy had injured himself in the stomach, but everything was OK. By the time Julia and I got to Columbia Hospital on 19th Street and Third Avenue, it looked like a gallery opening, you know? I grabbed one of the doctors and introduced myself and told him who Julia was, and they ushered her into another room. And that was the last I saw of her.

Later in the summer of 1968, as Andy recovered, I did some work for him, typing up diaries, mostly from tape recordings. Then he needed help again with silk screens. So I came back to the Factory for a while. I left for the last time around December 1970.

RFThe 1970s were a productive period for you writing poetry, but how did you earn a living?

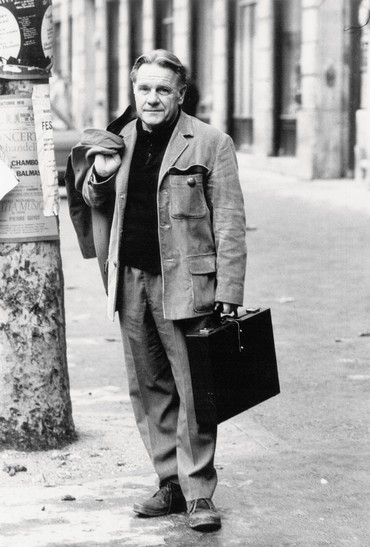

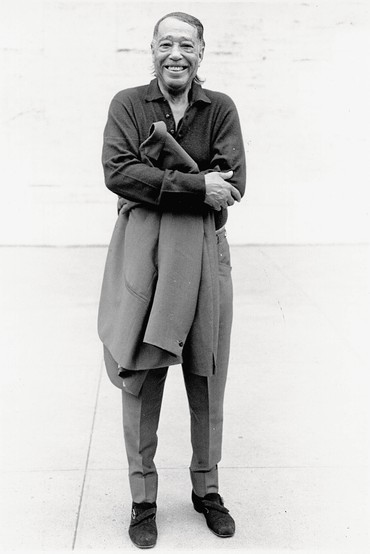

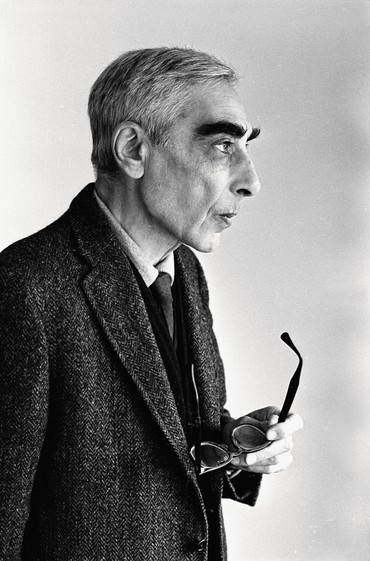

GMActually, the 1970s was when I began to take my photography seriously, and for much of the decade I made a living from it. In many ways it started with my portrait of the poet Charles Olson. The Paris Review was trying to do an interview with him and he wasn’t responding. I sent him a message, and he replied with a telegram: “Come Immediately!” I went up to Gloucester and interviewed him and photographed him. I really owe a lot to George Plimpton at the Paris Review for having faith in me to do the job. Not only did it turn out to be a very good interview but it pretty much launched my photo career.

RFI’ve been through your archives at the Beinecke Library at Yale, and you saved an enormous amount of material by Rene Ricard. Poems and letters and ephemera. It seems you were really devoted to him.

GMI was. He lived with me for many years during the 1970s and I saved everything of his I could. That material became the basis for his first book, 1979–1980 [1979]. I was hired by the Dia Art Foundation to oversee a series of poetry publications. That was the idea of Philippa de Menil [Fariha Fatima al-Jerrahi]. Heiner Friedrich was more interested in the art and Philippa was interested in poetry. She commissioned me to assemble an edition of Angus MacLise’s work—Angus was one of the original members of the Velvet Underground and he lived for many years in Kathmandu, where he had a bookstore and publishing house called Bardo Matrix Press. I also planned to publish John Wieners. Rene’s book was brilliant but unfortunately his behavior was so onerous that Dia canceled the rest of the series. Our friendship didn’t survive that publication either.

RFYou seem to have really come into your own as a poet in recent years, especially with these touching portrait or memoir-type poems written to departed friends. How did that series come about?

GMThat’s a good question. I’m trying to pinpoint a date. Let me give you a scenario: I went to Milan in 2004. I remember the date because I bought a newspaper and went to a café and read the obituary of Richard Avedon, who was terribly important to me. Then I was looking at my datebook, getting ready to go back to New York, and suddenly I saw that the next six months of my life were more or less completely blank. I mean, for the first time in my life I had nothing to do! And I’d always promised myself that I was going to read Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time [1909–22] in its entirety. When I got back to New York I started reading the books, all seven volumes. This was bedside reading, not sitting in the living room. It took me six months and two weeks to read the entire work—and it’s a real page-turner. It was at that point, although I wasn’t really conscious of it at the time, that my poetry started changing. I saw my life retrospectively—I saw myself being taken on a journey where certain things seemed so improbable, not even permissible, and I started writing with this awareness, doing things in my work that I felt I could never get away with.

RFSuch as?

GMWell, talking to the person that you’re writing about as if he or she were alive. That’s what I’m doing in the poems you mention: I’m basically channeling that person into my life, through poetry, in the way that Proust had done, to a certain extent. I’m not writing about the person, I’m writing to them, as if they were there in the room with me.

RFThe one constant throughout your life is poetry. I get the feeling you see poetry as a calling?

GMYes, and I’ve always believed in my guardian angel. For example, when I signed up for English class for the fall of 1959 in my senior year, I didn’t know who I was going to get for a teacher. I could have gotten any one of five English teachers, and I just happened to land in Daisy Aldan’s class. But what if I hadn’t? My life could have been something entirely different from what we’re talking about now, because I wasn’t writing poetry when I entered Daisy’s class, and within a couple of weeks I began writing poetry and I never stopped. If I weren’t a poet, I don’t know who I would be otherwise.

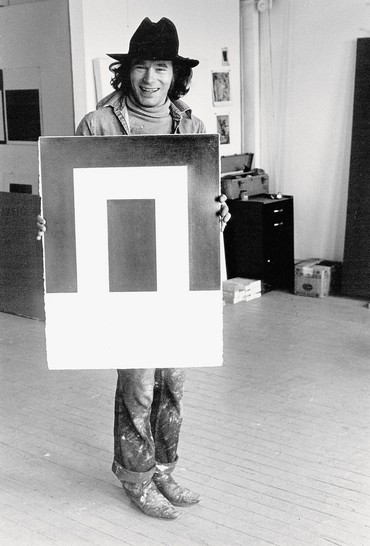

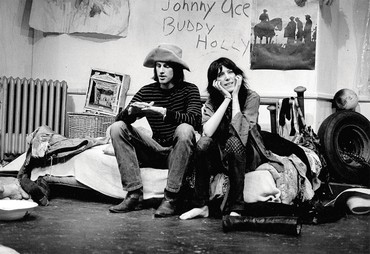

Photos: © Gerard Malanga