Ami Bouhassane is codirector of Farleys House & Gallery, the organization in Sussex, England, that manages the Lee Miller Archives and Farleys House, home of her grandparents Lee Miller and Roland Penrose.

Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at the Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames and Hudson in May 2021.

Antony Penrose is the founder of the Lee Miller Archives and codirector of Farleys House & Gallery, which manages the home and estate of his parents, Lee Miller and Roland Penrose. A broadcaster on radio and television, an author of podcasts, and a lecturer, he is also the author of two plays and ten books, including The Boy Who Bit Picasso (2010).

Jason Ysenburg joined Gagosian in 2014. He is the gallery’s liaison for the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation and the Estate of Tom Wesselmann and has worked on numerous exhibitions for the Richard Avedon and Andy Warhol foundations.

Richard CalvocoressiTony, it’s been over twenty years since we worked together in Edinburgh on a joint show on Roland and Lee at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. That was in 2001, Roland’s centenary year; how have things developed since then in terms of the perception of the couple’s work and reputation?

Antony PenroseThe Edinburgh show represented a massive turning point in the way we do things here at Farleys House & Gallery [the museum and archive in Sussex, England, where the couple once lived] because the people in Edinburgh were so generous in working with us that we came away with a really good understanding of how to put shows together. Although we’d done other exhibitions, we’d always been kept at arm’s length and not terribly involved. This gave us the courage and the opportunity to do a lot of our own shows afterward. One of the first was a direct spinoff at the Getty [Museum, Los Angeles], and then the National Portrait Gallery [, London] show together in 2005, and then the V&A [, London] in 2007. In a way, it was like Edinburgh was a coming of age. Yes, we’d done shows before but not quite with the rectitude and the research and everything we did on that occasion; it was a wonderful, wonderful experience.

RCIt’s very nice of you to say that. I remember the estate was a much smaller organization then than it is now. Can you say something about how the infrastructure has developed?

APIn those days there was Carole Callow, who was our fine printer. And we had a lovely lady called Arabella Hayes, the registrar and archivist. These two were everything for about ten years. The organization was tiny.

RCAnd then, Ami, about twenty years ago you became part of all this. How has your life changed in the last twenty years?

Ami Bouhassane[laughs] Well, I started by accident, really. I was pregnant with my first in 1998 and my dad said, “These people keep turning up at the house wanting to have a look at it and it’s kind of embarrassing. Can you help me develop tours of the house?” Tours were never part of the original business model when they founded the Lee Miller Archives. When he and my mum [Suzanna Penrose] and Roland set it up, the idea was the archives would work with museums and we’d represent the copyright and sell to collectors through galleries. We never dreamed people would come here, because this is the family home, why would you? Also, it’s in the middle of nowhere, no public transport, so it’s a mission to get here. But when dad’s book [The Lives of Lee Miller] came out, in 1985, people began to remember Lee Miller and make these little pilgrimages here. So we started these impromptu tours and he wanted me to help him develop them and work out a way we could be open to the public. That’s when I got bit by the Lee Miller bug. I ended up being an archivist part time. I had the baby and was guiding tours with her on my front, and then when she started adding too much to the tour commentary, she’d be on the floor upstairs in the office with Arabella [laughter].

RCDid you tell visitors that you were holding Lee Miller’s great-granddaughter? [Laughter] Since then you’ve worked alongside Tony on exhibitions and publications, and you’ve taken the lead on a number of different aspects of this operation.

ABYes, and now I manage the archives and the house. It’s grown from being a team of five people: now, all year round we have a team of fifteen, and then in the summer, when we’re open to the public, we grow to being more than fifty. So that’s quite a beast.

RCQuite an operation. When did you open the gallery?

ABWell, we soon realized when we started opening to the public that although people were coming to see Lee Miller and Roland Penrose’s home, what they didn’t think about before they came was, you don’t usually hang your own artwork in your home. So they’d come and want to see how Roland and Lee lived, but then they’d go away feeling like they hadn’t seen enough of, particularly Lee’s work, because in her lifetime she only hung three of her own photographs in the whole house. So we had a barn on the farm just next to us, which used to be the repair shop for the tractors, but dad had the idea of turning it into a gallery space. In one end we showed a selection from the archive that you wouldn’t get to see normally, and in the other we’d try to do what Lee and Roland did in their lifetimes, which was champion and promote other artists—sometimes Lee and Roland’s contemporaries: we’ve done a Dorothea Tanning exhibition, we’ve done Eileen Agar, Grace Pailthorpe . . . but we also show living artists, local artists, established artists, and it’s quite exciting to be able to use the space to share their work as well.

RCGetting back to the public perception of Lee. Tony, would you say that the emphasis now is more on her work as a war photographer, or as a fashion photographer, or as a portrait photographer of her artist friends—on whom this exhibition we’re working on for Gagosian is very much centered—or is it all of those things?

API’d like to think it’s all those things. It’s almost inevitable that the war photography attracts the most attention. And of course, whenever anybody thinks of Lee Miller, they tend to think of Lee in Hitler’s bath, and that kind of photograph—it’s sensational in the way that people tend to present war photography. But it’s only a very small fraction of her work, and gradually I think people are beginning to understand that, she’s not seen only from that perspective anymore: people recognize that yes, she was an amazing portraitist, yes, she was an amazing Surrealist photographer, and yes, she was an incredible fashion photographer. All of these aspects we are able to put forward in different ways, but I think it’s all coalescing now.

RCBecause all these different aspects fed off each other. They were interrelated.

APThey were. She could never have been the war photographer that she was without first being a Surrealist.

ABAnd we wouldn’t survive as an archive if we didn’t have that kind of breadth of work and experience that she had, because one of her strengths is that she covered so many different subjects and one can look at her work from so many different angles.

RCWhen I was doing the book on her work, I was reading all her dispatches from the front, which were published along with her photographs in Vogue magazine.

APWe published those as Lee Miller’s War [2020].

RCExactly. Her writing—and I know she found writing hugely challenging—but it always struck me that her dispatches were some of the most immediate, direct war reporting that I’d ever read. Is that an aspect of her work that people have picked up on?

ABDefinitely, that’s what got me.

APYes, writing got us both way before the images. And what was so fascinating about Lee was that her formal education was very minimal. She learned by doing. And she was never afraid to take on a challenge that she thought worthwhile. I think one of her greatest assets was the ability to know a good chance when she saw one. Beneath that she was incredibly well read. She knew James Joyce inside out and back to front—I mean, studying Ulysses [1922] in depth, that’s really the acid test of everything. She did a photo article for Vogue on James Joyce, and you can see how well she knew the work from that. She read everything from what she called penny dreadfuls to really highbrow stuff and just seemed to absorb it.

ABShe wasn’t pretentious. She hadn’t been trained to write, so she wasn’t trying to emulate some pompous person.

RCIt’s not an overly literary style.

APIt’s more of a journalistic one, on the spot.

ABYou feel like you’re on her shoulder.

APShe’s at a crime scene and she’s reporting.

RCExactly; it’s so immediate. In the war, she was allowed to go to the front where non-American combat photographers were not, I understand—

ABThe British wouldn’t allow women at all.

RCSo being a woman and being American put her in an extraordinary position, in a way. Do you think being brought up in America gave her a sort of confrontational, direct manner? I don’t know, I’m just thinking that someone English, more like your dad, Roland, would have perhaps been a little more reticent.

APBeing an American made her an outsider, in a way, and I think she had that slight distance that gave her an even more acute observation in Britain and France and the rest of Europe.

ABWell, you have to credit her parents as well, though, because they brought her up as equal to her brothers. She was born in 1907—in those days, girls were brought up to learn how to cook and clean and be a good wifey. They weren’t taught that they were equal. And it’s a big credit to both parents, particularly her dad, Theodore, an engineer, who encouraged her to invent go-carts with her brother. They didn’t mind that she got mucky and was daring.

APAnd played dangerous games.

ABThey gave her a chemistry set for her eighth birthday, which is really unusual for a little girl. So her baseline is different straight away. She was taught from a kid that she was equal, so when she got to be an adult, when people said “You can’t do that, you’re a woman,” she hit them with, “Well, why not?”

APAnd that’s not a typically American thing; that was very much a Lee Miller thing.

Jason YsenburgI think that level of independence is something we’ve tried to capture in the exhibition. It’s about telling a story of her strong sense of self. Another example is the short period when she came back to New York as a professional photographer and set up her own studio [in 1932].

APShe was connected to a front-runner: she was very close with the art dealer Julien Levy, and that really got her into all kinds of things.

ABWell, she made sure to have her ducks in line: She had offers of work from Vanity Fair, and she had Levy lined up as a dealer who promised to do her first solo show that December. Because she was from a middle-class family, she wasn’t like some of the early women photographers from Victorian backgrounds who started as hobbyists and were supported by their wealthy husbands. She didn’t have that luxury. And there was also that certain amount of pride. So coming to New York and launching her studio was quite an important step.

JYThere’s something about her focus that is quite extraordinary. When she set her sights on something, it happened.

API would never describe her as being self-serving or a go-getter, but she jolly well knew how to use her chances.

RCYou’ve recently researched and compiled and edited her and Roland’s letters. Can you say something about that?

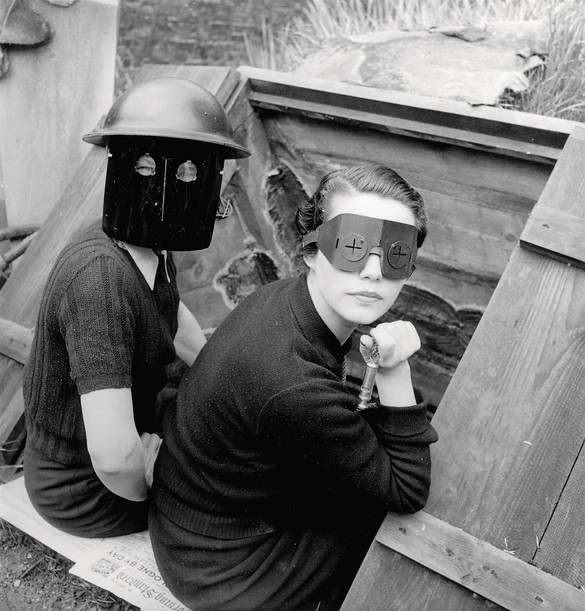

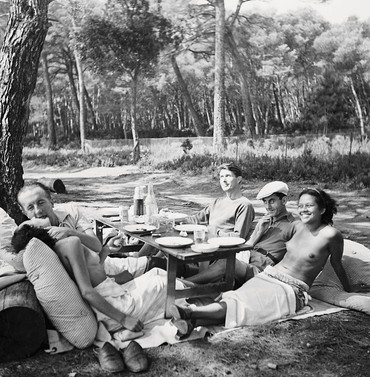

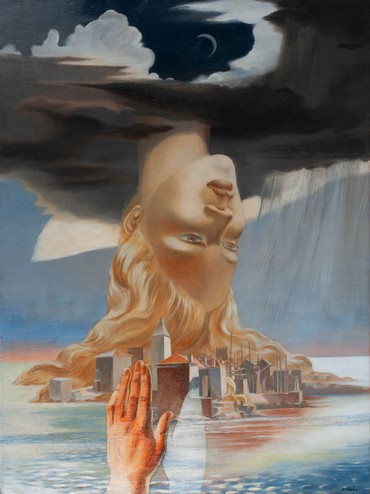

ABWe found these 300 pages of love letters between Lee and Roland from when they first met, in 1937. They met at a fancy-dress ball and he then whisked her off to what he called a Surrealist summer camp in Cornwall, where they met up with Man Ray and Max Ernst and Leonora Carrington, Ady Fidelin was there, Paul Éluard, Nusch Éluard—Henry Moore and Irina [Radetsky] rocked up and spent a few days with them too. They had a wonderful time there and then they decamped and went to the South of France and met up with Picasso and Dora Maar. That’s when Picasso painted Lee’s portraits.

So Lee and Roland had this wonderful kind of summer of love together, but by then she was actually married to an Egyptian man, Aziz [Eloui Bey], and had been living in Egypt for three years. Eventually that summer had to end and she needed to go back to her husband. And when they left and she went back to Egypt, she and Roland start writing to each other. There are kind of lovey-dovey bits [laughs], but what I loved about them was that they were gossiping about their mates and their mates just happened to be quite famous artists now [laughs]. So you get these little tidbits about how Max Ernst is having problems with Leonora Carrington and Marie-Berthe Aurenche, whom he was married to at the same time. But they’re also talking about the political situation, him in England, her in Egypt, as the war starts. And within that, she’s also writing about trips she’s done, how she’s gone and learned how to become sister of the serpents and how to train snakes and how she’s cross that her husband won’t allow her to have venomous snakes in the house [laughs]—for some reason he’s scared he’ll get bitten. It’s a lovely way into her Egyptian photography, and that group of friends, in addition to her relationship with Roland. It’s been great to compile all the letters, have that part of the archive out there and accessible to people.

We called the book Love Letters Bound in Gold Handcuffs [2023], because obviously they were writing to each other but they desperately wanted to see each other again. In 1938, a year later, they met up again and did a trip around the Balkans together, through Romania and Greece, mostly. Then Roland went back to England. He had to leave early; she continued traveling and went to Syria as well. And when he got back to England, he wrote this Surrealist poem, with his pictures.

RCThe Road Is Wider than Long.

ABYes, it became The Road Is Wider than Long. It was published in 1939 and it’s thought to be the first-ever British Surrealist photobook. It’s quite significant historically. So he went out to Egypt, leaving in January 1939 with the first published copy of The Road Is Wider than Long, in which he’d done some little color pictures and written this dedication. And he went out with that and a pair of gold handcuffs, designed by Cartier, to see Lee.

RCAnd Aziz, her husband, was prepared to let her go?

ABYeah, he was amazing. Quite early on, she wrote to Roland that she’d told Aziz about him, and in the letter she says, “Well, you know, he was a little bit upset but he then said to me, ‘Well, if you do leave me and divorce me, can I be one of your lovers?’”

APHe gave her money, he gave her his blessing, he gave her a boat ticket to London. And he loved her right until he died, even while marrying somebody else. And the extraordinary thing about Lee is that she chose her men very wisely, the ones that she was seriously committed to. Think about it: there was Man Ray during her time in Paris, really important. Then there was Aziz, generous, kind, very reliable. Then there was Roland and we know about him. And then there was [American photojournalist and editor David E.] Sherman. The men among themselves were also dedicated to each other: look at the closeness between Man Ray and Roland. A Frenchman once said to me, “The shortest distance between two men is the love of the same woman,” and I think it’s true. Roland wrote Man Ray’s biography, collected Man Ray’s work, and always promoted Man Ray.

RCSo coming to Seeing Is Believing, the current exhibition, curated by my colleague Jason: is this the first show that exposes or looks at the interconnected lives of these lovers, friends, artists, in a concentrated way?

APVarious single aspects have been looked at before but nobody’s ever really looked it as a generality, as an overall, have they?

ABAnd at that particular period as well, beginning with 1937. Before, it’s been mostly about the men Lee knew. That’s actually another reason we really appreciated working with you: whenever I used to go pitching to museums and directors and things, we’d often have to spend the whole time talking about the men Lee knew, and then in the last ten minutes we’d get to talk about how she was a great photographer. It was invaluable to meet curators like you who had the foresight and could recognize that she was a significant photographer in her own right and we didn’t have to do that spiel. Before, it had been very much about the kind of things that were done to Lee, the men who painted Lee, the men who did this or that to Lee. The kind of big muse.

RCOh, the muse bit.

ABIt makes us twitch, you know, because it implies that she didn’t have her own intelligence and input. Whereas this show really is looking at Lee. It’s quite bold, in a way, because it’s not just about her and her women relationships, it includes the men, but it really shows this equity between them as artists, the way they worked together. Those connections are quite well thought through.

JYIt’s interesting you say that because something that’s not often brought out in looking at this whole group of artists is the degree of collaboration. Not just collaborating in terms of Man Ray and Lee Miller, there are a lot of photographs on which they both worked and sometimes you don’t know whether it’s by Lee or by Man Ray or the two of them together.

ABWell, you still don’t. And if you read some of Lee’s later interviews, she talks a lot about working with Man Ray. She was only actually his assistant for the first nine months, but she talks about how within a year of being in Paris, she was doing all of his photography for him because he wanted to paint. And it wasn’t like, “I did his pictures for him, give me the credit,” it was like they were friends, they were lovers, they supported each other. And that’s what this show demonstrates: this group of artists were interconnected and they supported each other artistically. It wasn’t a competitive thing.

JYThe other aspect is the collaboration between a writer and a painter or a photographer, which is one of the great themes of Dada and Surrealism. It was as much a literary movement as a visual one. So you’ve got Joan Miró and Éluard collaborating on great portfolios.

RCÉluard and Man Ray.

JYAnd you have Lee and Roland collaborating.

APAnother one that I don’t know whether Jason’s thought of putting in the show is Jean Cocteau. Because he and Lee were very—

ABOh gee, you need a bigger gallery, Jason.

JYWell, hopefully what we’ve brought together tells a story that people will be captivated by and want to research further.

RCThis exhibition is very much about friendships that were formed in the ’30s and during the war and then continued afterward. So Roland and Lee went to America in 1946 and met up again with Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning and Man Ray and, who was it?

ABJuliet.

RCJuliet Browner, exactly. And when Lee and Roland settled where the house is, at Farleys farm in Sussex, they all visited and then more and more artist friends came down here. There was that great feature in Vogue called “Working Guests” [July 1953] where everyone is pretending to do something, like the philosopher A. J. Ayer, aka “Freddie,” bringing in the logs. When we showed that photograph in Edinburgh, a fellow philosopher, I think Anthony Quinton, saw it and said to me, “Oh, Freddie, doing something useful for once” [laughter].

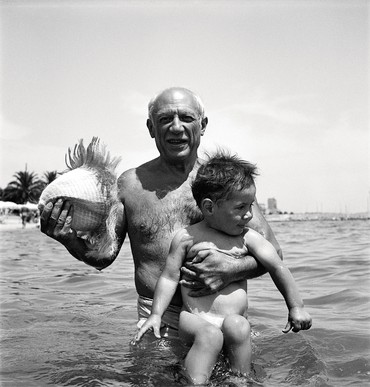

You were a little boy when Picasso came [in 1950], and the story goes you bit him and he bit you back. Do you remember a lot of those people staying the weekend?

APYes, I do; I just wish I remembered it with more clarity. But I was very young—3 1/2 when Picasso came—so some memories like that one in particular are kind of vestigial. I just remember that he smelled good and he was good on the hugs and cuddles and that. But later visits to his homes in France left much stronger memories. I was very fond of Man Ray. When I was really young he was not at all interesting. He just couldn’t see the point in children. Then when I was about fourteen or fifteen and I began to be interested in photography, that’s when we connected and he was absolutely brilliant. He wouldn’t show me how to do things but he would just quietly encourage me, particularly if I visited his studio in Paris. Max Ernst, on the other hand, was a bit scary because he would talk very loudly with a very strong German accent and throw his hands about, which was just a little bit troubling [laughs]. But there were others who were much more fun.

RCThere was a whole younger generation that came. Artists like Richard Hamilton.

APAnd John Craxton. The thing was, Roland and Lee were always so generous: “Oh, when you come to England, come look us up. Come and visit us, we live in the country.” And of course everybody would show up sooner or later. One of the reasons they came here to Farleys was the proximity to Newhaven, a port for the cross-channel ferry—Newhaven to Dieppe and then on to Paris by rail. The taxi drivers in Newhaven got so habituated to us that if somebody got off the ferry and looked a bit weird and didn’t speak English, they just brought them straight here. And it usually worked. That’s how we got the painter Jean Dubuffet, because he hadn’t a clue where he was supposed to go.

RCThey just brought him straight here with [poet and critic Georges] Limbour.

APExactly, him and Limbour. And of course it was here that Dubuffet met Richard Hamilton, and that started Hamilton off on the whole process that eventually became Pop art. It was just these amazing meetings.

ABOver some of Lee’s crazy cooking.

APThat was a kind of conversation piece if you like: Lee’s dinner. It started in the kitchen. Guests would arrive and they’d be immediately forced to peel potatoes or cut stuff up and drink vast quantities of whisky. And so finally when they wobbled through to the dining room, the party was already started.

Seeing Is Believing: Lee Miller and Friends, Gagosian, 976 Madison Avenue, New York, November 11–December 22, 2023