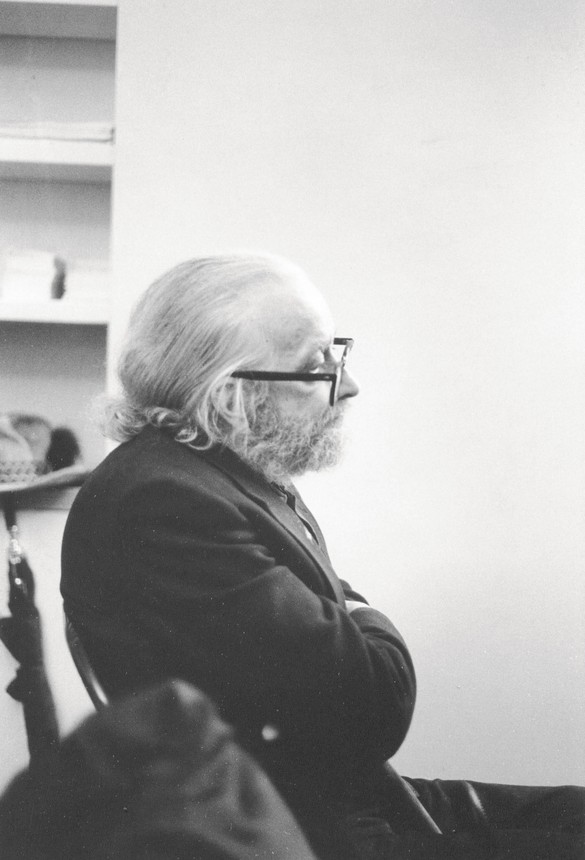

Raymond Foye is a contributing editor to the Brooklyn Rail. His most recent publication is Harry Smith: The Naropa Lectures 1989–1991 (2023). Photo: Amy Grantham

John Szwed is the author and editor of many books, including biographies of Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, Sun Ra, and Alan Lomax. He has received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation, and in 2005 was awarded a Grammy for Doctor Jazz, a book included with the album Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax.

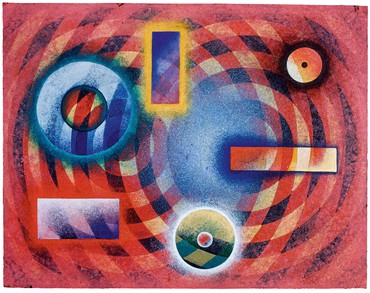

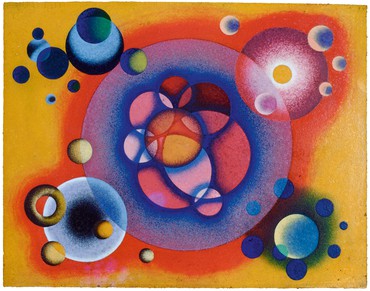

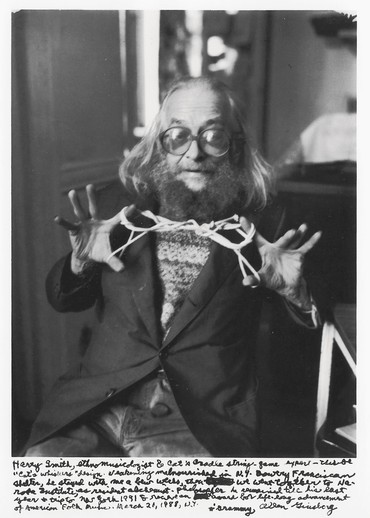

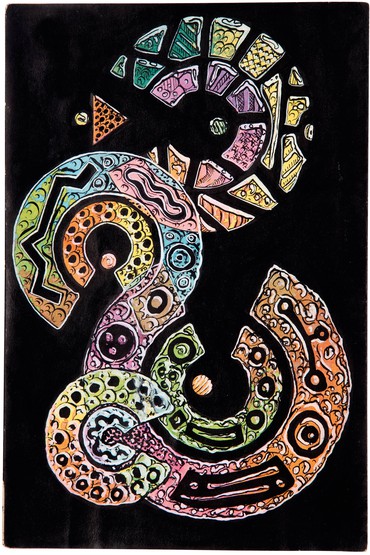

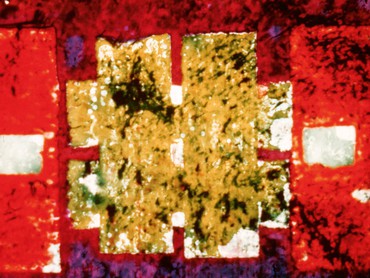

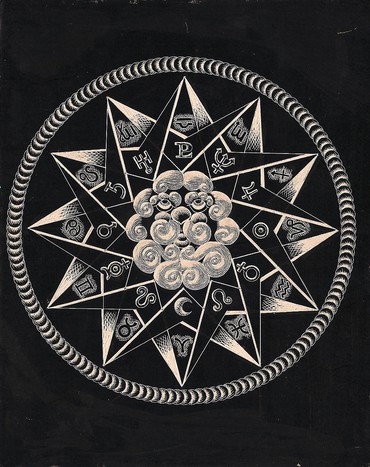

When Harry Smith died impoverished in Manhattan’s Chelsea Hotel in 1991, few could have imagined the posthumous fame that would follow. He was a legendary figure in the rarefied world of underground film, but his Anthology of American Folk Music (1952) would not be reissued for another six years and his visual art was completely unknown. Those works of his that were not long destroyed in the chaos of his life were scattered far and wide. But artists’ works have a way of making a space for themselves, and with each passing year Smith’s accomplishments—in film, painting, anthropology, musicology—have become increasingly germane to our time. His work is now enjoying a retrospective survey at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art (Fragments of a Faith Forgotten, October 4, 2023—January 28, 2024). Organized by the esteemed curator Elisabeth Sussman, the show is cocurated by Dan Byers, Director at Harvard’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts; the artist Carol Bove, one of Smith’s most important advocates, and the designer of the exhibition; and Rani Singh, head of the Harry Smith Archives.

John Szwed is one of the preeminent music biographers of our time (Sun Ra, Billie Holiday, Alan Lomax, Miles Davis). His most recent book is the improbably best-selling biography Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith. Few people are better qualified to tackle Smith’s multiple artistic personalities. Former professor of anthropology, African-American studies, and film studies for twenty-six years at Yale University, Szwed was also a professor of music and jazz studies at Columbia University and served as the chair of the Department of Folklore and Folklife at the University of Pennsylvania. Here, Raymond Foye sits down with him to discuss his book and approach to biography. Foye has written extensively on Smith’s work, was a personal friend, and with Singh curated the first exhibition of Smith’s visual art, at the James Cohan Gallery, New York, in 2001.

Raymond FoyeJohn, you write amusingly in the preface to Space Is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra [2020] that Sun Ra denied being born, avoided using words like “birth” and “death,” disallowed any earthly origins, and in fact rejected being human. His timeline stretched between ancient Egypt, Alabama, Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and Saturn. This sounds like very good preparation for writing about Harry Smith.

John SzwedThere are a number of similarities between Sun Ra and Harry Smith: both were unique, long lived, and created a mythology unto themselves. Both were virtual unknowns for much of their careers, who gave their lives, often risked their lives, for art that they knew was unlikely to be acknowledged. The complexity and effort that went into their life’s work was astonishing and daunting. I felt I should give as much as I could to their work, all the while knowing that my efforts would be meager and incomplete. Keep in mind that Sun Ra was a virtual unknown when I began that book.

RFLike Sun Ra, you were born and raised in Birmingham, Alabama. Is there some aspect of your childhood, growing up in that place, that shaped your vocation as a biographer?

JSOh yes, in so many ways. I have a strong memory of life in the South, from the bottom up—raised by struggling parents, living in a shotgun shack, visiting country relatives in even worse straits. Even as a child it seemed to me weird that they saw themselves as at least one step above their Black nonneighbors. Even weirder, that they admired so much about the lives of those they disdained. Then there was the music. It was impossible not to hear Black music of every kind on the radio, from gospel quartets to string bands, blues, jazz, rhythm and blues. The radio dial was the one place that wasn’t segregated.

RFYou’ve written some of my favorite biographies, yet every time I talk to you, you seem so disillusioned with the genre.

JSI’m not a fan of biographies, generally. There’s too much speculation, amateur psychologizing, that sort of thing. Martin Amis said it very well: “The trouble with life . . . is its amorphousness, its ridiculous fluidity. Look at it: thinly plotted, largely themeless, sentimental and ineluctably trite. The dialogue is poor, or at least violently uneven. The twists are either predictable or sensationalist. And it’s always the same beginning, and the same ending.” What I always learn after writing a biography are my limitations as observer and writer, and the arrogance of attempting to represent another person.

RFCome on, John, we’re supposed to be plugging a book. Cosmic Scholar has become hugely successful.

JSIt’s really weird. Harry’s carrying me, man. Both the Harry Smith and the Sun Ra books were hard sells, because they were virtual unknowns who had pretty much given their life for art. In each case only about two publishers were interested in either one of them. The editors said either that they hadn’t heard of him, or else they had heard of him and didn’t want to hear anymore.

RFThere’s something about Harry that just never ceases to fascinate, because the questions he asks are the questions of our times. But do you have a little bit of concern, as I do, that he’s going to be subsumed into the culture, the way our culture consumes everything and everybody? I guess it’s inevitable.

JSWell, I saw this happen with Sun Ra, who is now being celebrated as a forerunner of Afrofuturism—and I can buy that. But this image of him as a sort of Mister Rogers in space, a kindly, affable figure—the guy was scary! Even the musicians were afraid of him at times. It’s hard to get that across. He would change gears in a blink.

RFI know what you mean. I saw a photograph the other day of Harry in the Chelsea Hotel from the 1960s and it really brought back a side of him that was scary, manipulative, nefarious, diabolic. Not the genial figure he has become for most people today. I don’t think people understand just how dangerous and crazy he was. Were there any things you learned about him in writing this book that really surprised you?

JSOh, there were so many. It’s not a big thing, but the fact that he had no FBI file really surprised me, because everybody in the ’60s counterculture had a file, sometimes thousands of pages. On Harry they had absolutely nothing.

RFAnother good example of his magic. Was there a part of the story that was especially problematic?

JSI don’t think I ever got New York in the ’70s entirely right. It was overwhelming. It becomes very easy to forget that you have a subject in front of you.

RFOne thing I like about your books is that even though they’re about legendary figures, you strip a lot of the myth away, without diminishing your subjects.

JSTo see Harry as the quintessential hippie, or Sun Ra as a paragon of Black nationalism, it’s just too easy. It’s important to realize that no life is ever lived in the way a biography is written.

RFWere there any aspects of Harry that you couldn’t come to grips with?

JSThe occult and alchemy I never really got. There’s no end to figuring that one out. These were things I knew nothing about. I had to apologize to Harry’s friend Bill Breeze, who spent a long time with me, giving me documents and talking about Aleister Crowley and the occult. It would have taken me a year to get up to speed on that subject. Plus, what do we do when Harry is making fun of those things?

RFThis is a common trait of the shaman: on the one hand a magician, but on the other hand a huckster and a charlatan. You find this all through anthropological accounts. It’s all wrapped up into a very confusing and contradictory package.

JSI had to realize that I didn’t know enough about Harry to explain a lot of things about him. I even had to get up to speed on things that I knew about. I would beware of anyone who said they understood Harry’s whole life, or make that claim about anyone. I mean, what does it mean to know? The anthropologist Franz Boas notoriously told his students, who were collecting every bit of information in sight, that it was up to them to figure it out, and Harry said the same thing. He named all the things he was doing and said, Let somebody else figure out what it means.

RFA biography is many things: an outer life, an inner life, the work, the friends and colleagues, the times. As a biographer, how do you manage all these things?

JSHow did I manage it, if I did? It was by reading and listening to people who had lived in those eras and seeing if I could shine a light on the background without going off subject. Harry must have faced this problem too. You’ve got a lot of good stuff, but you’ve got to ignore some of it.

And that’s always the challenge for the biographer. How does one stay on track while at the same time branching off to explore these other lives? The people around the main subject are in effect character actors, yet often so appealing in their own right, and this was especially true for Harry. How do you avoid drifting off subject when you’re obliged to introduce them? With figures like Lionel Ziprin, Bill Heine, and many others, I kept putting the book down to research more about them. The curiosity becomes contagious. In many ways a biography is not so much about the person as about all the people who knew that person.

RFAnother question that comes up with biographies is, Where does the biographer draw the line in terms of the personal/intimate/erotic side of their subject’s life? What is off limits? What matters and what is simply prurient?

JSOne of the most-asked questions about people I’ve written about is their sexuality. I was accused by one reviewer of being too timid to “out” Sun Ra, so he did it, based on what he’d heard some people say. But we’ll never know what those people said, or if they even said anything. I think I could write a whole book about what I’ve been told about Miles Davis, for instance. There was a whole array of claims and contradictions on all sides of the subject. When once I asked where a person got a story about Miles, the teller said, “What, you want proof? Miles belongs to everybody.” And that’s the good and bad part of the story, right? Some things are too hard to write about convincingly.

RFYou must have a few favorite biographies by others?

JSActually, one book I really like in the genre is Bill Heward’s Some Are Called Clowns: A Season with the Last of the Great Barnstorming Baseball Teams [1974]. The team was called the Indianapolis Clowns and they were the last surviving team of what was known as the Negro Leagues, where many great major-league players got their start. They went from town to town and they were paid to play, and they would challenge local teams, what was known as barnstorming, and they were bizarre. The shortstop was seven feet tall, the first-base man only had one arm, some were clowns, contortionists, midgets. When they came out in the first inning the pitcher and the catcher were all they had. In the course of telling the story, all kinds of crazy stuff comes up, like wandering around South Carolina looking for the legendary Dr. Buzzard, a voodoo witch doctor who baseball players went to to up their averages. It was a large picture of this world outside of professional baseball where these people came from.

Now a similar thing in another book is Nick Tosches’s Where Dead Voices Gather [2001], which was supposedly a book on a white minstrel singer, Emmett Miller, but Miller doesn’t appear very often because the writer wanders so much. It’s not a conventional biography but it’s fascinating and it tells the story of an America that isn’t there anymore, a complicated mix of races and styles and cultures. Anyway, I call those “big picture” books and I really like how they set their subjects in place inside a much larger social milieu.

RFWell, both these books describe Harry’s life in a curious way: the traveling circus, the social irritant. That’s what makes for a great biography for me—a sense of the milieu, the social and cultural environment that the subject emerges from and is part of, and how the subject butts up against these norms.

Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, October 4, 2023–January 28, 2024